One humiliation followed another for popular sheriff Johnny Behan on that fateful October afternoon. He stepped into the middle of a tense situation to prevent a gunfight, only to see the bullets fly around him and three of his friendly constituents shot to death. Then Wyatt Earp nervily sassed Behan in the middle of the street, right in front of several citizens who would certainly spread the story throughout the town.

As the dead bodies were gathered from Fremont Street in Tombstone, Arizona Territory, Behan had a problem: How could he frame the events of the day to make himself look good? What would he tell the press? How would he face the lawmen Earp brothers when the tension had cooled? How could he spin humiliation into heroism?

While the sun set on Tombstone, he came up with one account. Then he changed his mind. And, in doing so, he forever transformed how future generations viewed the “street fight” known today as the Gunfight Behind the O.K. Corral.

Man About Town

Behan had that gift of likability, a great attribute for a politician. He could tell a joke or a good story, entertain a crowd and make friends wherever he went.

In Territorial Arizona, he became popular not just with the merchants and miners, but also with the crowd referred to as “cow-boys,” marginal ranch workers who often engaged in sordid activities. This group included the Clanton and McLaury families, who owned ranches that reportedly bought and sold cattle acquired from rustlers. Behan got along with everyone. Almost everyone.

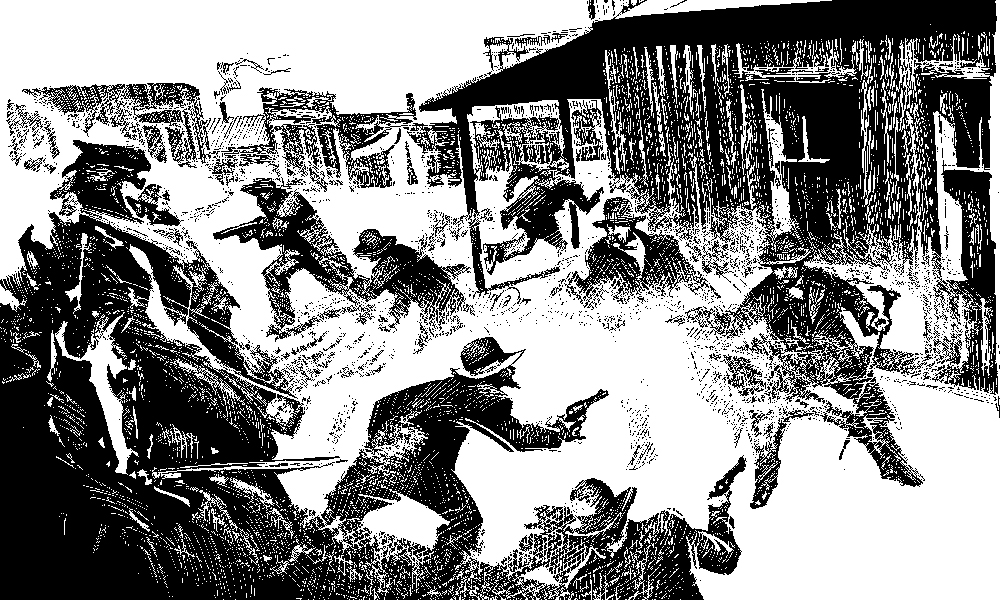

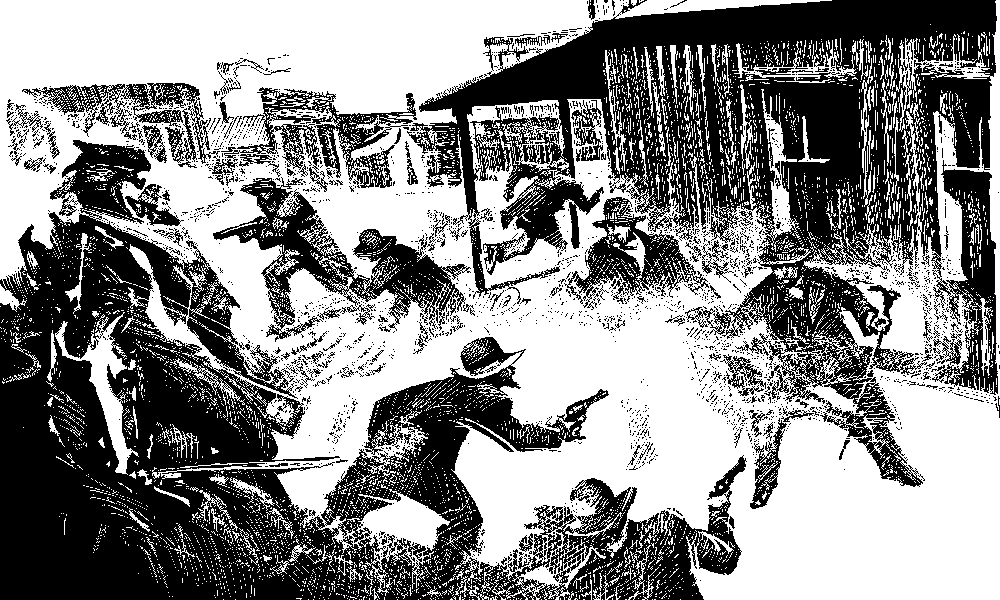

The well-liked sheriff slept late on that blustery day of October 26, 1881, awakening to find his town in turmoil. He tried to stop a tragedy by confronting Frank McLaury and ordering him to give up his guns. Frank refused and, minutes later, he lay dying with his brother Tom and Billy Clanton. After the shoot-out, Behan tried to arrest Wyatt, only to have the lawman publicly refuse.

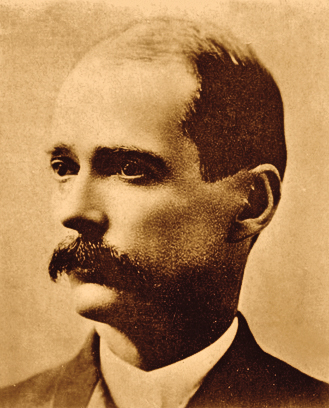

– Photo True West Archives –

In the aftermath of the gunfight, Behan attended three important meetings: He talked with Tombstone Nugget City Editor Richard Rule, he visited Wyatt’s wounded brother Virgil at his bedside and, in all likelihood, he spoke to Ike Clanton, who had turned himself in at the jail for his own protection. During the course of the evening, Behan changed his mind.

When the shooting ended, Rule scurried around town to learn the details. The Nugget was a Democratic, pro-Behan newspaper. On that fateful day, Harry Woods, both publisher and undersheriff to Behan, was collecting prisoners in El Paso, Texas. For Rule not to talk to Behan for his article would have been unthinkable.

Rule wrote his Nugget piece in a style of the day, telling the story, rather than using direct quotations, a method that left out attribution or sources. Rule did not identify Behan as a source, but the information could only have come from the sheriff.

“During the shooting Sheriff Behan was standing nearby commanding the contestants to cease firing but was powerless to prevent it,” the Nugget reported.

The battle began when Frank made a motion for his pistol, the newspaper stated, adding that Wyatt responded by drawing his pistol and firing, while Doc Holliday let loose with his short-barreled shotgun. Rule’s report that Frank had gone for his guns justified the actions of the Earp brothers and Holliday.

Rule probably would not have written up this version of events had Behan told him a dramatically different story that implicated the Earps in some wrongdoing.

When Behan visited Virgil’s bedside, Virgil recounted the fight to him, saying that one of the McLaury boys had drawn their gun to initiate the action. Behan told him, “I am your friend, and you did perfectly right.”

Then Behan made his way to the jail for a meeting that would shape history. Historians can never know with certainty what occurred when Behan sat down with Ike that night. Earlier in the evening, Behan had told both the Nugget and Virgil that the Earps were right in their actions. But something would change after Behan’s discussion with Ike.

Behan’s Surprising Testimony

Two days later, Behan told a different story at the coroner’s inquest. He testified that the first shot had come from a nickel-plated pistol held by one of the Earp crowd. He was watching the Earps, not the cow-boys, so he could not testify about whether one of them had also made a motion for a gun.

In the weeks that followed, Behan became a key witness in the preliminary hearing known to history as the “Spicer Hearing,” in which Judge Wells Spicer presided over extended testimony to determine whether enough evidence existed to bound over the Earps and Holliday for a jury trial. Ike had filed the murder charge against the Earp contingent. History does not record why Ike, instead of the Territory of Arizona, filed the charge, but the most likely reason was so Ike could hand-pick his attorneys to prosecute the case, instead of leaving it in the hands of District Attorney Lyttleton Price. Ike amassed a dream team of prosecutors, led by brothers Ben and Briggs Goodrich. The Earps countered with excellent attorneys of their own, led by Thomas Fitch.

As the hearing ensued, Ike, Billy Claiborne, local merchant Billy Allen and 19-year-old Wesley Fuller all testified that they had seen the Clantons and McLaurys surrendering when the Earps and Holliday fired upon them.

Under oath, Behan testified that he had his eyes on the Earp party as they fired the first shots of the gunfight.

But Behan had a motive to lie.

Wyatt was angling to run for sheriff in the November 1882 election. The two had not been friendly for months, after Behan reneged on his promise to make Wyatt his undersheriff for the newly formed Cochise County. By late 1881, Wyatt may have been keeping time with Josephine Marcus, Behan’s former live-in lover who had left the sheriff when his affections strayed, although no evidence has been found to support this claim. At the very least, Behan had political reasons to want Wyatt out of the way.

Fitch Sets His Trap

Behan’s testimony during the Spicer Hearing resembled a delicate tightrope walk, where he avoided directly contradicting what he told Rule for the Nugget article. He was watching the Earps, so he could not have seen the actions of the Clantons and McLaurys. If the ranchers made a motion for their pistols, he would not have known.

During cross-examination, Behan’s responses became particularly interesting. One enticing question was, “If anything, how much have you contributed, or have promised to contribute, to the attorneys who are now prosecuting the case now associated with the district attorney?”

“I have neither contributed nor promised to contribute one cent,” Behan answered.

Yet more than a century later, an important detail has become public. Behan did make a contribution of sorts. He served as guarantor on a loan to Ike during the hearing, an action that would be as dubious then as it is now.

Fitch asked Behan what had transpired during his visit with Virgil on the night of the gunfight. The sheriff stoutly denied that he had ever said he saw one of the McLaurys draw his pistol to begin the fight, or that he had uttered the words, “I am your friend, and you did perfectly right.”

Fitch stopped his cross on the subject. He had the testimony he needed. Fitch had set his trap.

Weeks later, on November 28, Fitch called Winfield Scott Williams to the stand. Williams had recently been appointed an assistant district attorney by Price. He likely would have to work with Behan on future cases, which made his testimony shocking.

When Behan came to call in on Virgil, Williams had also stopped by for a visit. He testified that he was there when Behan arrived. He then confirmed Virgil’s version of the meeting, saying that he had heard Behan say one of the McLaurys initiated the action, as well as tell Virgil, “I am your friend, and you did perfectly right.”

Williams took the stand to essentially call Behan a liar. This was a pivotal moment in the case and a critical element to understanding what actually occurred that day in Tombstone.

Justice Prevails

A few days later, Justice Spicer would determine that there was not enough evidence to show a likelihood of conviction, and the Earps and Holliday were not bound over for trial. The long, agonizing hearing ended, and the Earps returned to the streets of Tombstone.

Behan had every motivation to lie when he took the witness stand. He had the chance to eliminate his rival and improve his political position. An intense examination of the evidence makes it appear that lying is exactly what Behan did. He told one story to Rule and Virgil before he met with Ike, when they cooked up a much different, darker story that could carry the Earps to conviction, perhaps even to the noose. And he left behind a puzzle for historians to ponder and debate for more than a century.

Casey Tefertiller is the author of Wyatt Earp: The Life Behind the Legend.

He is working on the forthcoming book, The Last Deputy.