The dirt road to Mangas almost loses itself amid low hills as it winds through the windswept plains of New Mexico’s high desert.

It isn’t a drive for the faint of heart. Or the directionally challenged.

Just when getting lost in this time-forgotten patch of nowhere seems unavoidable, signs of life rise out of the scrub.

Outside Quemado, 15 miles off U.S. 60, the ghost town of Mangas is little more than a few crumbling adobe buildings, dust and endless sky. This is private land, owned by the cattle operation, Mangas Ranch. People who wander in out of the dust simply aren’t welcome.

That is what an aged man bellows at me, or something to that effect. Short and wiry, he dismounts a sputtering tractor and strides toward me across the corral, where just moments ago he was stacking bales of hay. Apparently the patch of brown grass in front of an old house where I stopped isn’t a good place to park.

“You gonna drive into my living room?” shouts the man, stomping across his front yard. He doesn’t get many visitors out here. Most days, he’s hard at work on the ranch, the old man snaps at me.

“Or talking to writers from Phoenix,” he says, finally cracking an impish grin.

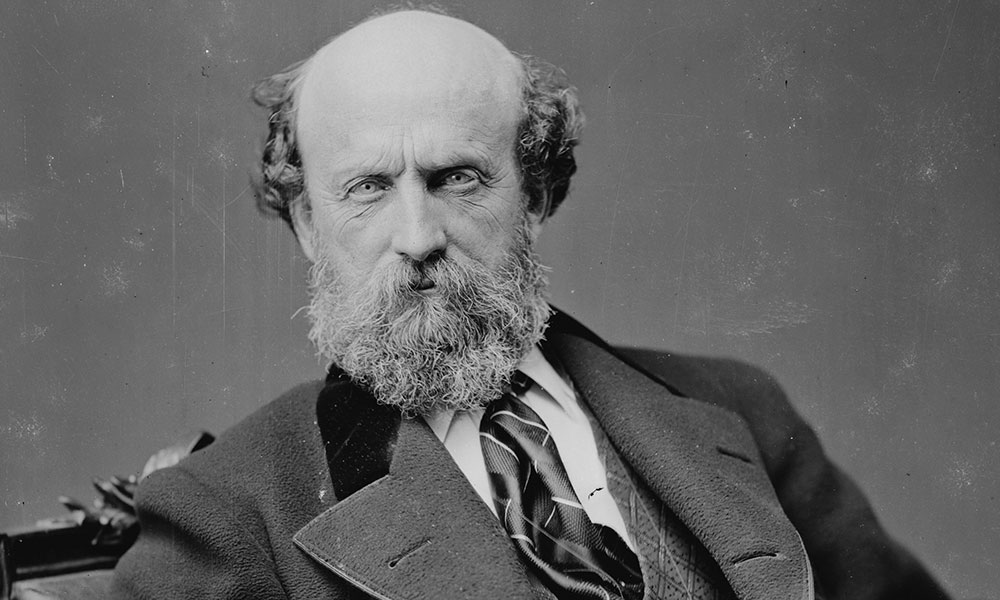

This place could take its name from Mangas Coloradas, chief of the Chiricahua Apache. It was once within his homeland, which reached across the Rio Grande into Mexico and out west into Arizona.

Mangas, a conflicted man, alternately terrorized and then reached out to strangers. By the mid-1860s, he and the Apache were embroiled in a war with the Army. Soldiers finally captured Mangas at Fort McLane, near present-day Hurley.

His death was as terrible as it was treacherous. With a promise of peace, the Army lured the aged warrior to meet them. Then they tortured and killed him. His mutilated remains now lie somewhere in western New Mexico, or so the stories go.

There are rumors about his grave site. Perhaps it’s among these crumbling adobe buildings, deep in Apache country?

At Mangas Ranch, it’s hard to say if this man is as coarse as he lets on or just trying to scare off city slickers. Drawing a smoke from the pack in a breast pocket, he leans against a fence post and identifies himself as Narciso Baca, the 63-year-old owner of the ranch and few buildings that sit here.

“The city, the metropolis,” he calls it, noting his wife is also a resident. “We fight all the time about who’s Mayor.”

Baca wears a sweat-stained baseball cap pulled low over his weathered face. Dark sunglasses hide his eyes. He lights his cigarette, takes a drag and begins to unravel the story of Mangas Coloradas and this place. As Baca talks, his country drawl at times slips into a Spanish accent.

“I was born here,” he begins.

He tells me Mangas was founded when Spanish settlers moved to the region in the mid-1800s. As they farmed and raised cattle, Mangas grew into a bustling town.

“That whole hill was full of buildings,” says Baca, pointing at the barren terrain. “It was the only town in Catron County.”

A generation of children then budded from the resulting encounters between the Apache and the Spanish. Mestizos. Baca says he’s one of them.

“[Mangas Coloradas] is my kinfolk. This was his campground,” Baca says. “They used to go through here to trade, and they’d stop to feed the horses.

“I was born as a result, I guess.”

Losing Your Head in Mangas

Six hours earlier, I was speeding east on the way out of Phoenix, chasing the legend of a great Apache, dead certain I was headed to find a lonely grave somewhere.

Outside the urban sprawl, the highway near Apache Junction squeezes down into two lanes, with the Superstition Mountains looming in the distance. I drove past towering Picketpost Mountain, while to the north stood a plateau called Apache Leap.

Up there, desperate Apache warriors chose to plunge to their deaths, rather than die at the hands of pursuing U.S. Cavalry. The tiny bits of obsidian scattered among the rocks are called Apache Tears, for the wives and children of those doomed braves.

The highway then blows through Superior and Globe, dusty towns founded in the 1850s, whose fortunes rose and fell with copper and silver mined in the area. Long before the first prospectors plunged shovels into dirt, this was Apache country.

In 1846, Mangas signed a treaty, allowing passage through Apache lands so the U.S. could fight the Mexican Army, long an enemy of the Apache. Mangas, who stood well over six feet tall, was a diplomat, both among the scattered bands of the Chiricahua (his daughter married Cochise) and to the U.S.

The treaty ended in violence. A rancher’s stepson, Felix Ward (better known as Mickey Free), was kidnapped. To get back the boy, the Army dispatched 24-year-old George Bascom. He suspected Cochise. Rather than attack, Bascom invited the Apache to meet for a conference in 1861. It, and the ensuing events, came to be called the Bascom Affair.

When the Apache convened at Bascom’s tent, soldiers surrounded them. In the ensuing fracas, Cochise escaped, but his brother and five warriors weren’t so lucky. Cochise retaliated and took white hostages for an exchange, but he killed them when Bascom asked the boy be included. The soldiers hanged the captured Apache. The treaty between the Apache and the Army was over.

After decades of bloody conflict, the Apache saw themselves defeated and confined to reservations. Two of these, the San Carlos and Fort Apache, are divided neatly by the rushing Salt River and a majestic canyon of the same name.

Through there, U.S. 60 winds its way down to the river, to a rest area smelling of burned-up brake pads and panic. Maybe due to the white-knuckled slalom on the way to the bottom.

Up and out the other end lies Carrizo, Arizona, a tiny Apache community, just east of Salt River Canyon. There, Scott Cody, 42, of the White Mountain Apache, stands passively watching horses lazily pick at straw and nuzzle a water trough.

Cody is a lifetime resident at this place with nothing but a general store, a smattering of small houses and streets that dead-end into the wilderness. Life here is steady but slow, Cody says.

“Out here it stays quiet,” he says. “You can pretty much ride horses all day without seeing anybody.”

Cody has heard stories about Mangas Coloradas, passed down from tribal elders. The chief will likely spend the afterlife wandering the spirit world, searching, he tells me. “When you leave some things behind, you’re still looking for it,” Cody says. “That’s the way we were taught.”

Mangas Coloradas left behind his head.

Before his death on January 17, 1863, Mangas sought another truce with the Army. He was 70. He’d been fighting for years and had been wounded several times. Some 3,000 troops were looking for him. It was time for peace.

But that wouldn’t be the case.

“Somehow, somebody got a lucky shot,” says Cody, of the surprise attack on Mangas. “He was the biggest guy they ever seen.”

At Fort McLane, soldiers cut off the chief’s head, boiled away the flesh and shipped off his skull for scientific research. Accounts have the skull going to either the Smithsonian Institution or a phrenologist in New York City. It remains lost to this day.

A Trail of Blood

Springerville, Arizona, sits roughly 10 miles west of the state line. At nearly 7,000 feet in elevation, the city is cool and the sunlight intense. But it’s dark inside Tequila Red’s Cantina, where a few customers are hiding from the afternoon sun and swapping jokes. The harsh guffaws end abruptly when I plop into a stool and start asking around about Mangas Coloradas.

“Mangas was a mean S.O.B. He fought against my relatives,” says Travis Armijo, a 43-year-old resident of Springerville.

“I remember my grampa saying stuff,” notes Armijo, between tugs on his beer.

Mangas and his warriors terrorized the Armijo family back when they were among the first homesteaders in New Mexico, he says, adding “They fought all them Indians.”

Between the 1846 peace treaty, cut short by the Bascom Affair, and the chief’s death in 1863, miners and ranchers crowded onto the Apache homeland. Skirmishes were frequent. In 1860, miners attacked an Apache camp near the Mimbres River, killing four men and kidnapping a dozen or so women and children. Mangas stepped up his raids. With the Civil War underway by that time, settlers had little protection against marauding Apache, led by Cochise, Geronimo and Mangas Coloradas.

Today, the outpost of civilization nearest Mangas is Quemado, an unincorporated community in New Mexico of about 5,300, sitting at the foot of the Continental Divide.

Locals tell me I should talk to Eric Skrivseth, chairman of the 53-member Community Advisory Board. He also owns the local hardware store. Skrivseth knows I’m in town looking for him, sees me first and calls to me from across the street.

Quemado doesn’t get a very steady stream of visitors, the 47 year old says.

The population around Quemado has dwindled, he tells me. Homestead farms failed after the turn of the 20th century. The slide continued through the late 1980s, when Interstate 40 was completed and started drawing traffic off U.S. 60.

The settlement of Quemado happened to coincide with an Apache declaration of war following the Bascom Affair. “When the Apache were in the final round of trying to hold onto their land, people all through this county were vulnerable,” Skrivseth says.

That evening in Quemado, as sunset falls over the quiet streets, it seems to me the perfect time for pondering the past over a beer. Except there’s a shortage of liquor licenses in New Mexico. The nearest available beer is a 42-mile haul east to Datil, at the end of a winding crawl up the Continental Divide. It’s a nice drive.

As U.S. 60 climbs, the elevation starts to yield pine trees. Sugarloaf and Madre Mountains squat on either side of the road. Just off the highway in Datil sits the Eagle Guest Ranch: a convenience store, gas station, motel and café.

The place has been in Carol Spears’s family for more than 50 years. The white-haired matron won’t divulge her age, save for she’s “old enough to know better.” Spears seems taken aback when she hears the impetus for my trip here.

“There’s more to life than liquor,” says Spears, rolling her eyes.

Maybe, and the beer did warm up on the drive back to Quemado. Still, better than nothing, I think, popping open a longneck and diving into one of the books about Mangas Coloradas I brought along.

The chief was killed under the orders of Brig. Gen. Joseph Rodman West, who’d agreed to discuss peace with the Apache.

“Men, that old murderer has got away from every soldier command and has left a trail of blood for 500 miles on the old stage line,” one account quotes West as telling his troops. “I want him dead or alive tomorrow morning, do you understand? I want him dead.”

The soldiers shot and buried Mangas, reporting he’d attempted to escape. Several days later they dug him up to remove the head. The warriors who accompanied Mangas to Fort McLane were set free and returned home. The story drops off without mention of his final resting place.

The end of the Apache Wars came with Geronimo’s surrender in 1886.

Grave to Nowhere

At Mangas Ranch, when I finally tell Baca about my quest to find Mangas Coloradas’ grave, it’s clear to me that he has heard all this before. He lets out a long breath of smoke, taps the butt and shakes his head. The chief isn’t here, he says. In fact, Mangas Cemetery is named for the town, and only the bodies of ranchers and their families rest there.

“Try Pinos Altos,” he kids. “Or maybe Silver City.”

As far as Baca goes, he says he’s fine where he is, given all the fighting, killing and dying men tend to do. People don’t come out to Mangas often.

“I don’t have a lot of respect for human beings,” he adds, as the sun sets over Mangas. “That’s why I stay out here.”