Somewhere, Fred Harvey, a visionary from the 19th century, is smiling down on Allan Affeldt, a dreamer in the 21st century.

Somewhere, Fred Harvey, a visionary from the 19th century, is smiling down on Allan Affeldt, a dreamer in the 21st century.

Fred Harvey was a plain working man who became the “quintessential American entrepreneur.” He helped “civilize” the Southwestern United States with his string of Harvey Houses—15 hotels and 47 lunch and dining rooms along the Santa Fe line by his death in 1901. Harvey Co. continued to build hotels and restaurants until a Hawaii hotel chain bought it in 1968.

In Winslow, Arizona, Harvey built a traditional hacienda named La Posada, designed by the legendary Mary Colter. In Needles, California, he created El Garces, a neo-classical railroad station that was one of the last great Santa Fe-Harvey hotels. Both would eventually be abandoned and abused.

Allan Affeldt just didn’t think that was right, but he wasn’t looking to save anything when he came to Winslow, Arizona, in 1994. “I just came to look,” he says. “La Posada had been put on the endangered list of the National Trust for Historic Places, and it was on the disposal list of the Santa Fe Railroad.”

Allan and his wife Tina Mion saw that La Posada was beautiful and could be beautiful again, and they found a whole town thinking the same thing. Two local women had been working tirelessly to save what they could: Janice Griffith of the Old Trails Museum and Marie LaMar of the Winslow Historical Society led the way. Griffith got La Posada registered as a historic site, and the two women marshaled the community to becoming “Gardening Angels” to tend and water the hotel’s gardens to keep them from dying.

The big stumbling block, of course, was money. It would take millions to restore the hotel, and after it was restored, what would you do with it?

At the time, Allan was heading a think tank in California for architectural professionals, teaching them responsible development. Like Harvey, he didn’t have a personal fortune, but what he lacked in funds, he made up for in determination. And, like Harvey, Affeldt had a plan. La Posada should become what it once was; it should again be a hotel, with a fine restaurant and why not add a Western museum?

The City of Winslow was so impressed with his plan, it gave him negotiating power with the Santa Fe Railroad, handed over ownership of the hotel and awarded him rights to a state grant toward restoration.

“With old buildings, it’s not what it costs to buy the place, but what it costs to restore it,” Allan says. “But La Posada is one of the most important buildings of 20th-century American architecture.”

His first rule of historic preservation is this: “It doesn’t do enough to restore—you have to think about making it useful. There has to be a revenue stream, or else it becomes a drain. So it’s not enough to be a historian or an architect, you also have to have business sense.” He happily reports La Posada is such a successful hotel again, its occupancy rate is 95 percent. (And, oh yes, Allan is now the mayor of Winslow.)

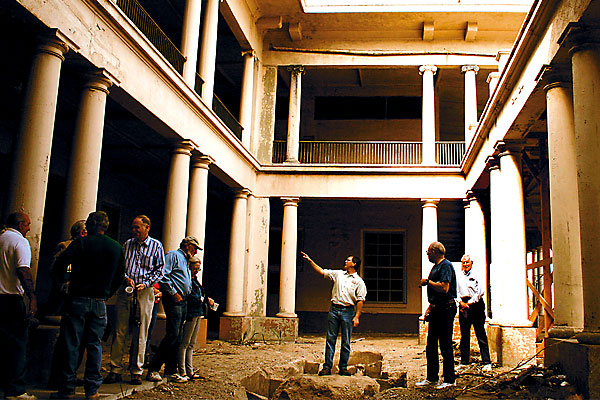

He’s applying the same lesson to his newest project, El Garces in Needles. This hotel was built in 1908—a building originally 500 feet long with 16-foot-high ceilings that is a “forest of columns” and is considered the “most important neo-classical train station remaining in California.” It operated as a hotel until 1949 and has been abandoned since 1988.

Earlier this year, Needles City officials expressed their delight as they helped Allan break ground on the rehabilitation of El Garces. “I’m going to do the same thing I did with La Posada,” he tells us. “It will be a hotel, restaurant, visitor center and museum.” He hopes to reopen it in December 2008, which would mark its Centennial Year.

His second rule of restoration is “you have to tell great stories—you have to be engaging.” He notes that “people hunger for more information,” so historic sites should include old photos as well as video tours and walking tours. His third rule is “pay attention to beauty—not every building is worth saving.”

He acknowledges that not everybody can pull together the dollars it takes to embark on one of these mega-expensive projects. “But you never know where the resources will come from and when you’ll get that combination of preservation passion and business sense. That doesn’t mean you can’t start. Even if all you can do is mothball it to keep it from destruction—that’s an important step.”