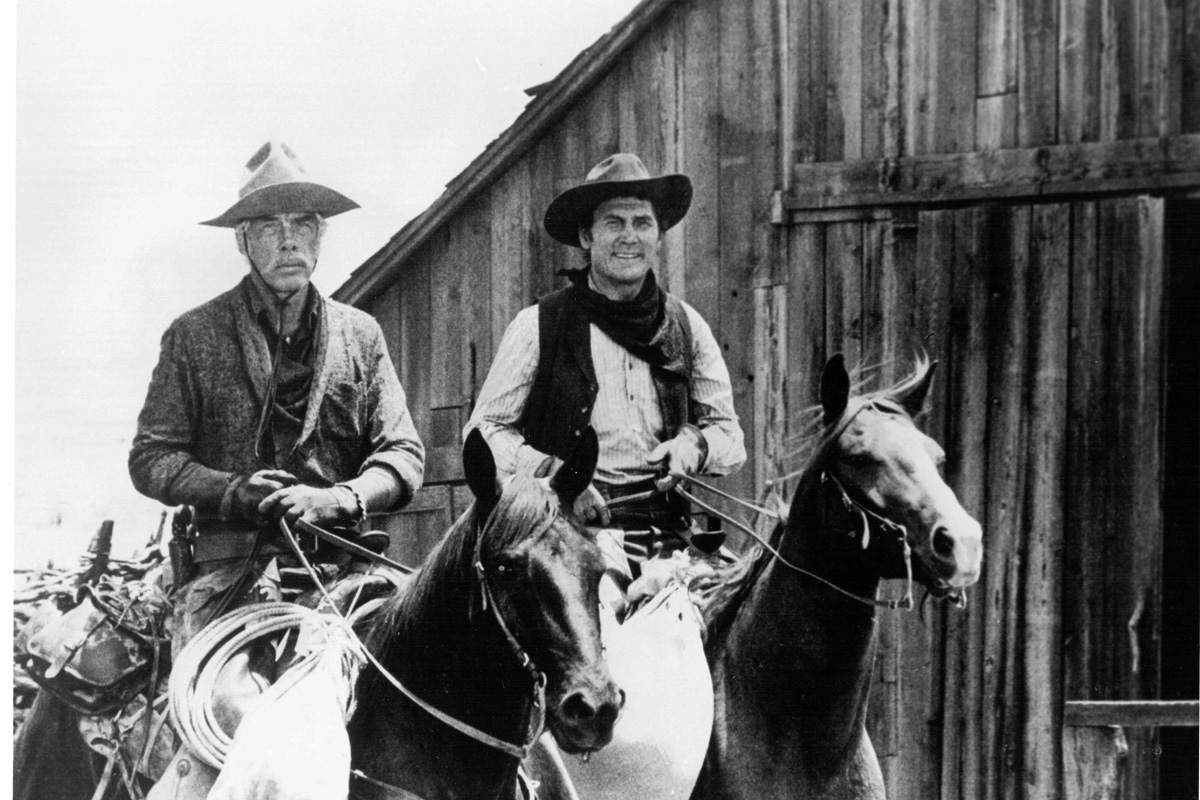

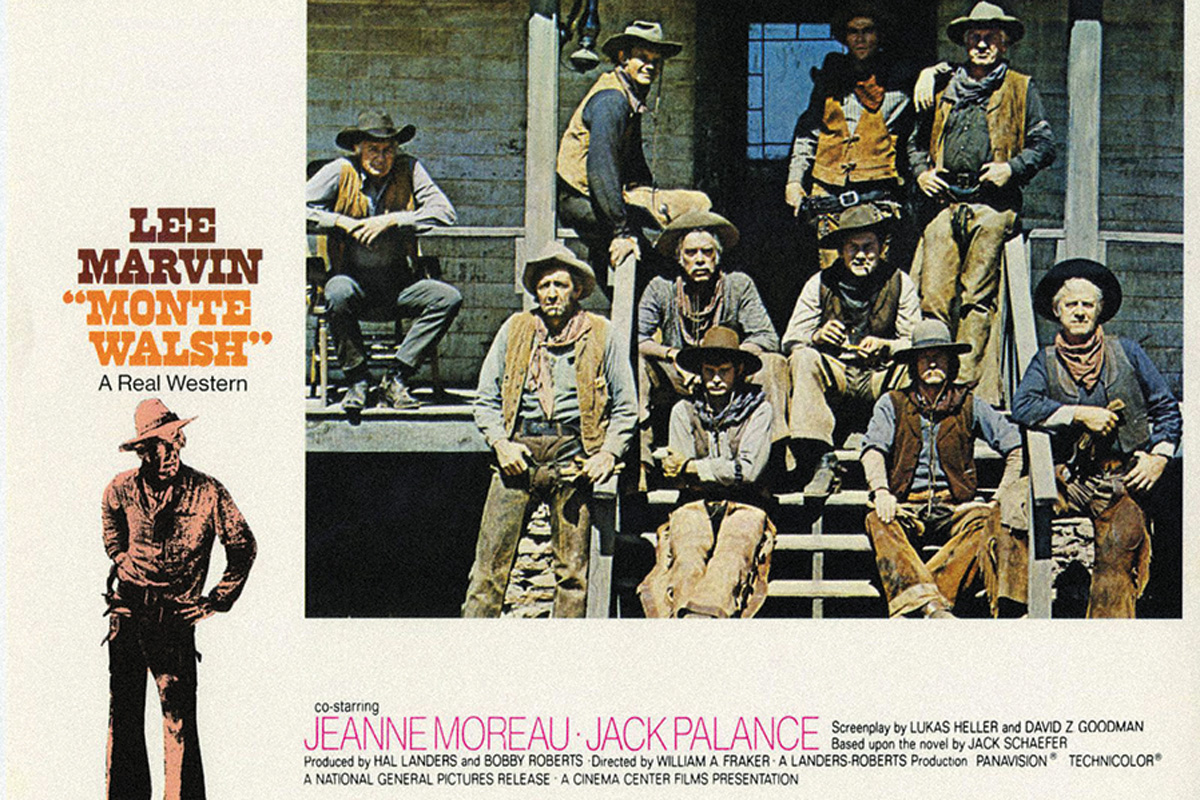

The film Monte Walsh turned 50 this year. Like so many fine Westerns of its time, it was about the end of the Western era, but unlike most, it wasn’t about outlaws, like The Wild Bunch, or gunfighters, like The Shootist. It was about hardworking, honest cowboys, typified by Monte (Lee Marvin) and Chet (Jack Palance), whose world was disappearing before their eyes as ranches merged into vast tracts controlled by faceless syndicates, their assets to be stripped. Its relevance has only grown with the years.

Critic Roger Ebert gave it four stars, but cautioned, “This may be the first three-handkerchief Western.” It is by turns uproarious, sweet, wistful, contemplative, exciting, tragic, and suspenseful. Monte Walsh got made because producer Bobby Roberts wanted to make a movie with his Malibu neighbor Lee Marvin, asked Marvin’s girlfriend Michelle Triola for a suggestion, and she said Monte Walsh.

The rambling Monte Walsh novel was not the obvious Hollywood home run that author Jack Schaefer’s tight and taut Shane had been. It’s more a collection of character sketches than a story, and screenwriters Lucas Heller and David Zelag Goodman surgically isolated the best vignettes to create a plot.

Marvin, a decorated World Wat II Marine, a star “heavy” since 1962’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, became a leading man with his Oscar-winning comedy performance in 1965’s Cat Ballou.

William Fraker was a great cameraman with deep Western roots—he’d started as assistant cameraman on The Lone Ranger—but he was directing for the first time. Cinematographer David Walsh was promoted from camera operator; his photography was often heartbreakingly beautiful. Palance was a great villain but was daringly cast as a nice guy. Mitch Ryan, best known for the vampire soap opera Dark Shadows, was cast as Shorty, who goes to the dark side when his horse-breaking job is eliminated. “Jack [Palance] and I talked about the complexities of Shorty,” Ryan recalls, “about how much of a challenge both our parts were, because his was a very sweet, shy kind of a guy. He said it was much more complicated than it looks like.”

open-range cattle days.

The film’s cast was a perfect mix of seasoned hands like growling Jim Davis as the Slash-Y range manager and youngster cowhand Bo Hopkins, fresh from The Wild Bunch. “I was thrilled to death, even though it was a small part, just to work with Lee and Jack Palance,” recalls Hopkins.

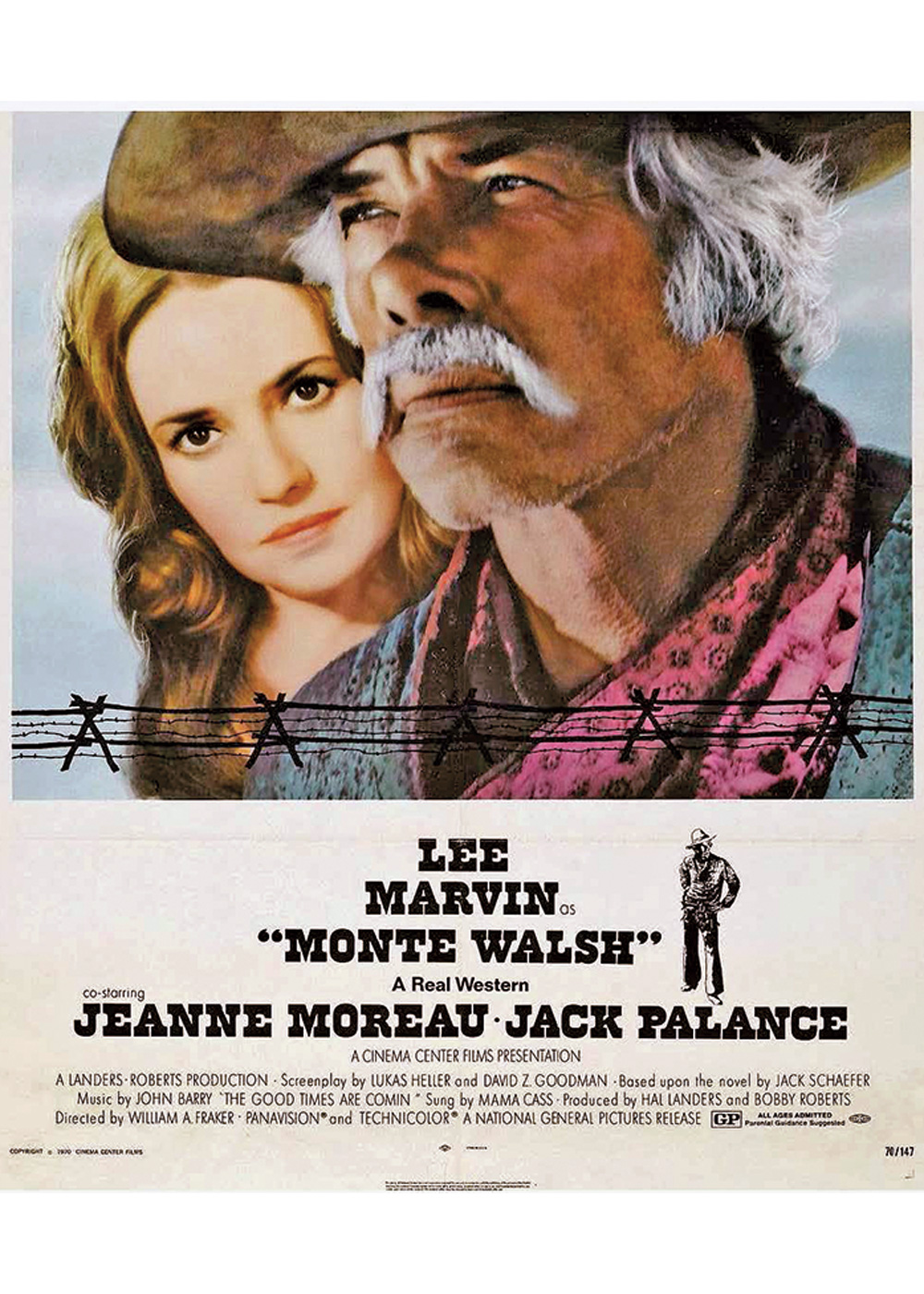

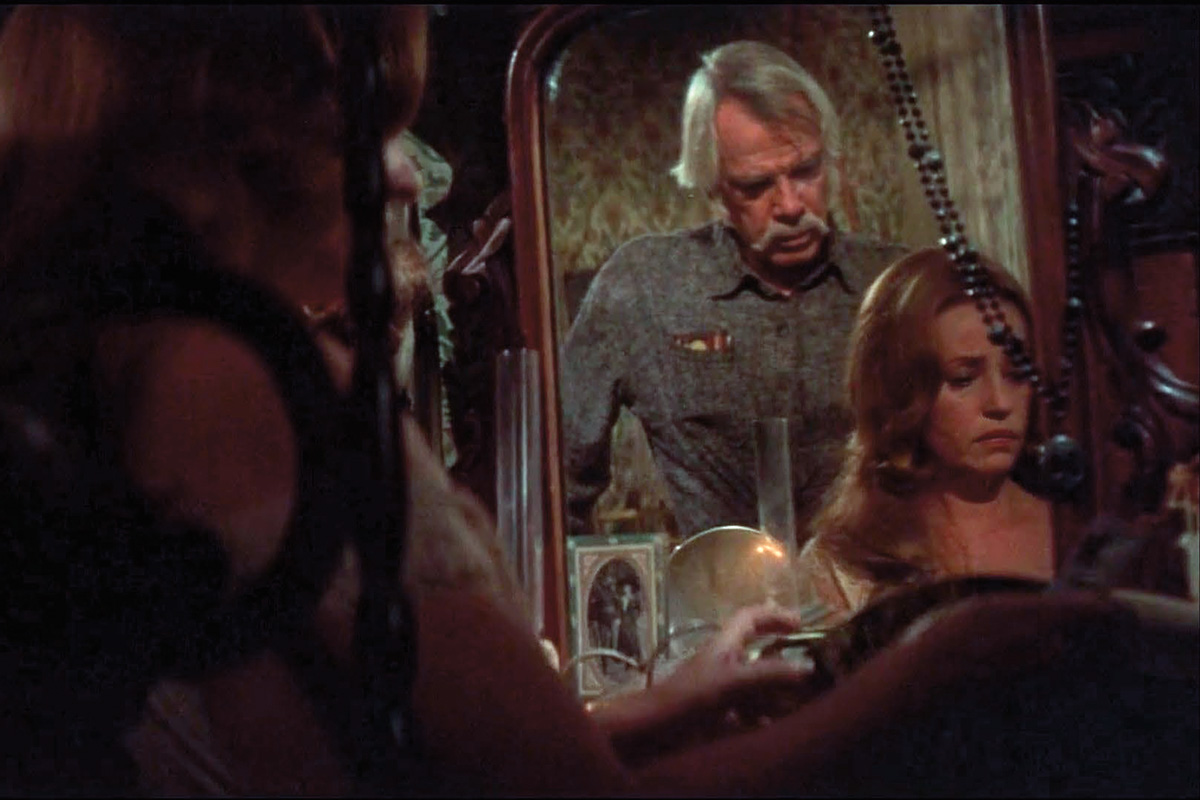

Perhaps the finest stroke of casting was international film star Jeanne Moreau in her only American film appearance; she’s luminous as Martine, the prostitute who loves Monte.

Memorable set pieces include a mustang drive and a familiar bunkhouse brawl, made special with touches like the cowpoke removing his dentures before joining in. The most copied is the sequence in which the cowboys, unable to enjoy the cook’s good food because of his foul odor, drag him to a water tank and scrub him, followed by his revenge.

The film succeeds largely on Marvin’s portrayal of Monte, and his behind-the-scenes involvement. “He was a meticulous actor, down to the barbwire cuts on his arm, things that make a performance marvelous,” Ryan remembers. “He helped me pick my wardrobe.”

co-star in Monte Walsh and play the prostitute and love-interest, Martine Bernard. Their mutual admiration blossomed on and off the set into a screen romance, which makes their scenes some of the best—and most believable—of the film.

The wonderfully weaselly Matt Clark, as a cowhand and occasional bank robber who leads Shorty astray, recalls, “Lee said, ‘I’m gonna tell you a secret. I do half of my performance in the wardrobe fitting.’”

When Chet quits cowboying and marries The Hardware Widow, Monte begins to rethink his own future. He asks Martine why they never married. “Because you never asked me.” He asks her then, and although she says an immediate yes, it turns out to be too late to make it work.

A saloon scene in which a lawman draws on Clark while he’s with Billy Green Bush and Ryan, leading to Ryan killing him, was simple on the page but a logistical nightmare. Clark remembers riding to the set with the other actors and “Lee is drunker than Cooter Brown. I said, ‘This doesn’t make sense. I’m not going to pull a gun when he’s standing there with a gun on us!’ So Lee said, ‘What if you have your arm on the bar…’” And Marvin choreographed the scene, positioning the three outlaws so that Bush could slip a gun to Clark that the lawman couldn’t see. “If Lee’d been interested in anything other than catching blue Marlin and drinking, he could have been one of the best directors going.”

– Courtesy Todd Roberts Family Collection –

Fraker went on to direct the infamous Legend of the Lone Ranger but redeemed himself when he returned to cinematography for Tombstone. Palance would win his Oscar 22 years later, like Marvin did, for a comedy, City Slickers. Marvin would go on to many more great performances, but Monte Walsh would be the last straw with him and Michelle Triola, who sued the producers, claiming partial ownership of the film. She also sued Marvin and lost both cases but introduced the word palimony to the English language.

Blu-Ray Review

Rachel And The Stranger

Loretta Young is Rachel, the bonded servant woman whom recently widowed William Holden buys—and marries for propriety. But he and his son treat her like a servant until backwoods-but-charming Robert Mitchum comes along and makes them realize what they’re in danger of losing. Norman Foster’s direction is elegant, Waldo Salt’s screenplay is full of clever charm, there’s a terrifying Shawnee attack and cabin-burning scene, and Mitchum sings six songs! Great entertainment.