Following the Great Sioux War of 1876-77 on the North-ern Plains, the various bands of Lakota Indians yielded at agencies in Dakota Territory and Nebraska or sought refuge in Canada. In May 1877, the Northern Cheyennes, who had previously surrendered at Camp Robinson, Nebraska, were escorted by Army troops to join their southern kinsmen at the Darlington Agency in the Indian Territory in present Oklahoma. They had lived on the Northern Plains for decades, and the sudden exile of 937 of them to this foreign environment affected them profoundly. With scant food, over the next year the people suffered starvation and homesickness amid humid, disease-prone conditions. The winter of 1877-78 proved especially brutal for them, and dozens perished.

On the night of September 7, 1878, some 300 Northern Cheyennes, led by Chiefs Little Wolf and Dull Knife broke away and headed north from Darlington in a gambit to reach Montana. Over the following weeks, soldiers and Indians collided as the Cheyennes wended north through Kansas and into Nebraska. The tribesmen further raged against citizens en route, destroying property and killing settlers. As they plied the land north of the Platte River in Nebraska, the respective followers of Little Wolf and Dull Knife separated, the former heading for the Yellowstone River country in Montana Territory, where they peaceably yielded to troops in the spring of 1879.

Those with Dull Knife fared much worse. In late October 1878, famished and distressed amid increasingly cold conditions, that chief’s followers, numbering 149 men, women and children, submitted to a cavalry patrol and proceeded as prisoners to Camp Robinson in northwestern Nebraska, where they occupied a vacant cavalry barrack. After two uncertain months, the government resolved to return them to Darlington, although the people stated their preference to die rather than go back. In early January 1879, to compel their compliance, post commander Capt. Henry W. Wessells, Jr., cut off their provisions, and during the night of January 9, 1879, the desperate people staged a breakout, killing and wounding several soldiers with guns and ammunition they had secreted in the barrack. During their rush, 40 Cheyenne people were killed or wounded, while another 55 were captured.

The garrison of 3rd Cavalry troops re-sponded swiftly, yet many of the tribesmen succeeded in scattering into the hills and getting away. For two weeks, soldiers pursued them west of the post, now redesignated Fort Robinson. Skirmishing occurred along Hat Creek Road, a rough-cut corridor through wooded hills west of the post. Near midnight on January 16, Wessells’ command bivouacked 20 miles from the fort. The next morning, as soldiers proceeded beneath a looming bluff, warriors let loose a distant volley, killing Private Amos Barber, then swept in, stripping Barber’s body of weapons and ammunition before racing off.

On Sunday, January 19, Captain Wessells’ command reached Bluff Station, north of present-day Harrison, Nebraska. Major Andrew W. Evans arrived from Fort Laramie with two companies of the Third Cavalry and took command. On the 20th, Wessells’ troops reconnoitered northeast for trails. Evans with his companies searched ridgelines until that afternoon, when his men exchanged shots with warriors ensconced along a distant pinnacle called Castle Rock.

Early on January 21, with two companies and Lakota scout Woman’s Dress accompanying, Wessells searched bluffs northeast toward Hat Creek for 10 miles. He related that while “going around the base of the bluff, a corporal [and] a private of my company and myself saw plenty of moccasin tracks. Soon after, more were discovered by Woman’s Dress. I started on the trail. We followed out about 3 miles from the bluff and found a dead beef killed by Indians and soon after lost the trail.” As night fell, Wessells moved closer to the foot of the bluffs and “almost immediately saw a camp-fire. I went to it and saw…some men of my company [H] who had been sent ahead during the afternoon to look for the Indian trail. They told me that they had discovered the whole thing….”

The Northern Cheyennes, meanwhile, had sustained no significant losses in their brush with Major Evans’s soldiers on January 20th. They regained the prairie floor and set out toward the Sioux at Pine Ridge Agency, 60 miles away. There they hoped Lakota friends and relatives would provide them food and shelter, and they might blend with the population. The Indians planned to navigate the fingered courses of Antelope Creek and other routes trending that way while maintaining sufficient distance from patrolling troops. During the night of January 20-21 they covered eight or nine miles before stopping to rest and build fires for warmth and roasting whatever meat they still carried. Then they moved on. With ammunition low, they wanted no further soldier encounters. Altogether, they were led primarily by Little Finger Nail, whose stature had grown since the breakout. They numbered 32 people-—17 warriors and 15 women and children.

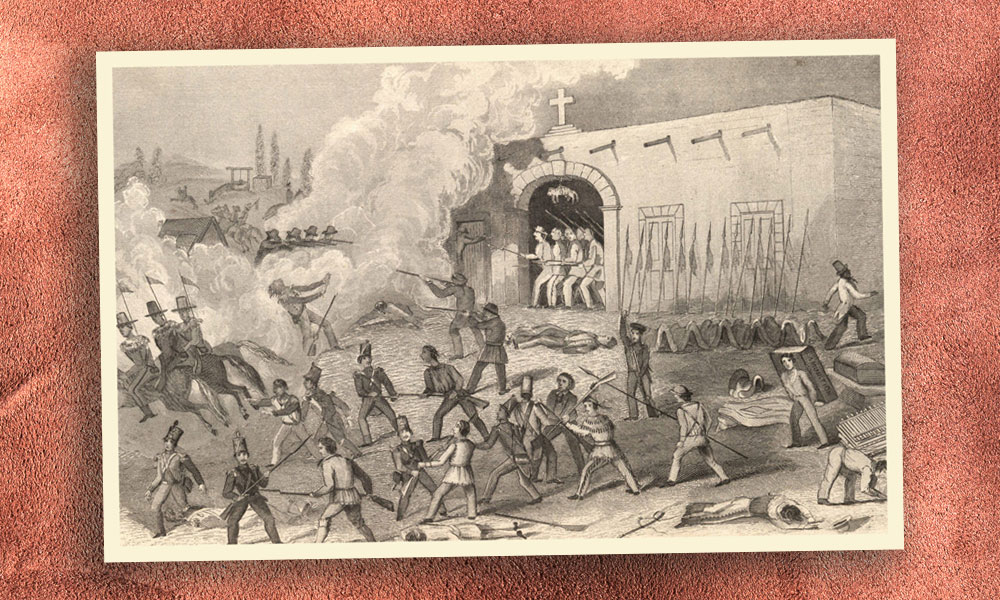

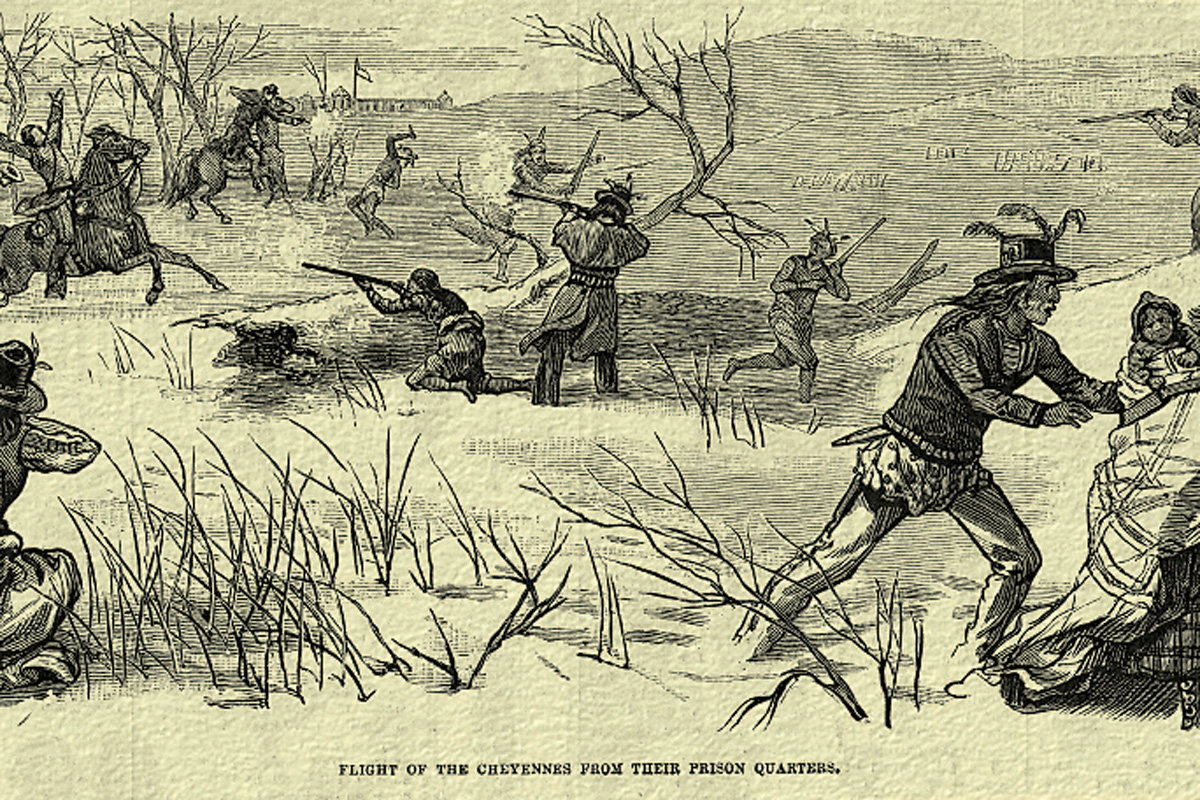

shows an artist’s interpretation of the Northern Cheyennes’ January 9, 1879,

breakout from the barrack prison at Fort Robinson.

– Courtesy Author’s Collection –

Continually fearful of the troops finding them as they crossed the prairie, the Cheyennes sought secluded places where they might evade discovery. When darkness settled, they moved on. Still, they left footprints in the melting snow, evidence of their passing that Wessells’ soldiers had detected. Ascending the brim of a low rising grassy escarpment before dawn, they found what they thought would be a safe hiding place. Located some 13 miles northeast of Evans’s skirmish site, and eight or nine miles northeast of Bluff Station, the surviving clutch of Dull Knife’s people settled into what would seem a natural entrenchment—a large blowout perhaps 35 feet long, a dozen feet wide, and between three and six feet deep.

The refuge offered only modest protection, but occupied high ground. Situated 25 feet above the trifling streambed of Antelope Creek, it enabled the Cheyennes to survey the adjacent plain and upland approaches to the south and west. The people improved the setting by digging with knives to modify rude natural breastworks. At the west side of the pit, a two-foot wide gulch ran down 50 feet to the tributary of Antelope Creek, which provided a meager water source. The stream’s webbed complex of rivulets coursed a few miles east to Hat Creek, which in turn headed north.

Cognizant of their precarious circumstances, the people hunkered beneath the lip of their make-do redoubt. They planned to pass the day until darkness enabled them to proceed on their course. Some of them must have realized the site’s vulnerabilities. If the troops found them there, they were trapped, yet if they moved on, they were sure to be discovered. In this manner, the balance of Dull Knife’s people reconciled themselves to their dilemma atop a gentle bluff overlooking Antelope Creek.

The troops, in fact, were close at hand. Early on January 22, a morning Wessells would recall as “clear and pleasant,” the captain’s command found the Indians’ trail as it passed through a large prairie dog town. His men proceeded ever closer to the rising ground on the northeast. Arriving from Bluff Station with 2nd Lieutenant Francis H. Hardie that morning, Scout Shangrau brought word that the supply wagons were en route. After advancing a mile or so, Wessells directed Lieutenant Chase to move ahead and to the left of the column, with Shangrau, Woman’s Dress and two Company A soldiers as an advance guard.

The troops proceeded in this manner for two miles, at last approaching a slightly timbered and sage-covered bottom fronting the area of the Indians’ concealed position atop the bluff. Therein, Little Finger Nail, Roached Hair and the other Northern Cheyenne men had caringly painted their faces, prepared for any exigency. The women, children and elderly took shelter as best they could, bracing for discovery and the climax that now appeared inevitable.

Near one o’clock, as the Army scouts came within several hundred yards of the rising ground, shots rang out from the Cheyennes’ lofty berth, immediately felling Shangrau’s mule. Shangrau and Woman’s Dress ran for cover in the bottom growth while the advance guard pulled back. Directly behind, Companies A and E dismounted and returned fire. Wessells ordered Lieutenant Chase to dismount and hold his position. For several moments, Chase’s men returned fire toward the Cheyennes’ entrenchment, and in the brief exchange Woman’s Dress received a gunshot wound to his arm. Private Henry A. Dublois of Company A also fell wounded from his saddle, his horse shot beneath him. To keep the Cheyennes in place, Wessells sent Chase with Company A to take position below and opposite the bluff top while the balance of the soldiers waited expectantly for Lieutenant Baxter, who was to arrive with Company F.

As they paused, Wessells, who maintained a 200-yard distance from the Indians, determined to surround them and attack on foot from several directions. With Companies E and H, he moved north of the entrenchment, directing Captain Lawson to advance with E on his left and secure a location to cover the Indians. Below and some 125 yards southwest of the tribesmen, Chase’s Company A completed the encirclement, effectively “hemming them in on all four sides.” Appointed troopers thereupon removed most of the company mounts to secure ravines or sheltered areas beyond range of the Indians’ guns. Lieutenant Chase meantime dispatched riders on the back trail to hasten forward Baxter and Company F. Wessells presently directed interpreter James Rowland to call out to the Indians that the women and children “would be protected” if they came forward. There was no response.

From these several positions, the soldiers girded for battle, sporadically exchanging shots with the Northern Cheyennes over the next two hours or so, until Baxter and his unit at last arrived, increasing Wessells’ immediate force to four understrength companies totaling 100 men. On Wessells’ direction, Company F took position below the Indians and across Antelope Creek, while Chase and Company A proceeded “to a point occupied by Capt. Lawson’s [E] company and thence down the ravine [that led] in the direction of the Indians’ position.” Chase’s men took cover behind a crest and “prepared to charge the rifle pits occupied by the Indians.” Baxter’s Company F covered Wessells’ and Chase’s units during the maneuver. After the companies had realigned to complete the investment, Chase reported to Captain Wessells, who laid out his plan. He explained that he would “advance up the ravine from the position his company [H] then occupied [north of the Cheyennes’ entrenchment], and at a given signal the two companies [H and A] would charge the ravine together.” In short, the combined force would comprise a semicircle “so as to bring the right and left of the line respectively toward the edge of the steep creek bank,” where the Indians were sheltered. A detachment of Company F would also later move to advance from the east, while the remainder of that unit stayed in the bottom to monitor the west side of the Northern Cheyennes’ position.

Prior to opening the attack, Wessells told his command: “We have lost enough men now waiting for these Indians, and we must charge them.” Company A men pulled off their overcoats and arctic overshoes to enable them to move more freely. Before the assault could proceed, however, Chase sustained a grievous loss to his unit when Sgt. James Taggart was abruptly killed by a carbine bullet to his neck as Company A took position 50 yards from the Cheyennes’ pit. At that, Chase’s men suddenly took the direct brunt of the ensuing opening melee. As Chase recalled, “I found my men subject to a flank[,] rear[,] and front fire. I determined not to wait for the arrival of H Company, but ordered an immediate advance on the rifle pits of the Indians. We came under their fire at a point about 12 yds distant [and east] from [the east side of] the pits. The Indians raised from the pits as my men…[reached] the crest and volleys were simultaneously exchanged. Farrier [George] Brown of my company was killed here.”

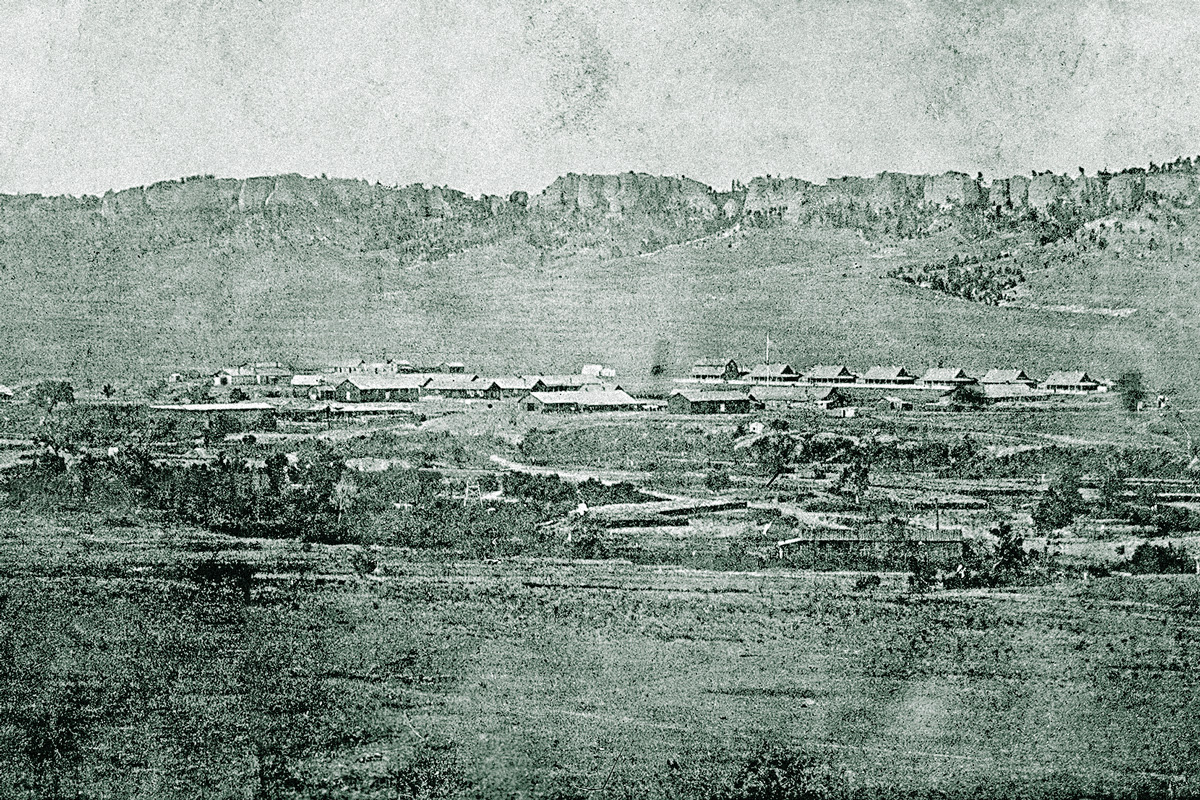

– Photo by Victor Gondos Jr Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration, No. 70168742 –

Lieutenant Chase described the continuing engagement: “The Com-pany then advanced to within about 5 yards of the pit and fired two or three volleys into it. Capt. Wessells [,] seeing ‘A’ Company in action [,] moved at double time and within 5 or ten minutes had surrounded the pit with his company and a few men from the other companies. In the meantime Pvt. [George E.] Nelson of my company was [also] killed. From this time [forward] I did not see an Indian take aim except the one who [subsequently] wounded Capt. Wessells with a revolver. The line fought in this position for nearly three-quarters of an hour during which time Captain Wessells twice ordered the firing to cease and called to the Indians to surrender and come out. The answer in both cases were shots from the Indians. The firing eventually ceased. I formed my company in line [and] directed that the bodies of the Indians should be taken from the pit. Upon removal it was ascertained that 17 bucks were dead and one buck wounded. There were eight women and children alive and seven women and children dead.”

Chase remembered certain hesitation among the troops in finally surmounting the crown of the Indians’ defenses, as well as specifics about the wounding of Captain Wessells: “[During the assault] we found it difficult to force the men onto the crest of the pit occupied by the Indians. I called around me men [from Company A] whom I thought I could trust. Capt. Wessells did the same in his company [H]. Capt. Wessells and I walked side by side with cocked pistols[,] determined to lead the few men around us up to the very edge of the pit. As we advanced

I saw an Indian’s head and his hand with

a pistol in it raised above the other Indians, but not above the level of the crest. Captain Wessells and I both fired. The Indian fired

at the same time, the bullet taking effect in Capt. Wessells[’] head. Capt. Wessells staggered. I caught him to prevent his falling, ran back with him about 15 yards to where I found a place out of the range of fire. I then went back to the skirmish line [and] told the men Capt. Wessells was wounded and called for a general advance on all sides.”

Another felled by a bullet in the assault was First Sergeant Edward Ambrose, of Company E, who survived.

Following the wounding of Wessells, as Chase reported, “the men now rushed right to the very edge of the pit and fired, I suppose, 200 shots into it, and again fell back some six or eight yards. The line wavered backward and forward within 10 yards of this Indian rifle pit for some 10 or 15 minutes after Capt. Wessells was wounded.” It was quickly apparent that the fighting was over. When the soldiers closed at last, most of the Indians were dead or immobile from wounds, their shots trailing off as their ammunition played out. At the very end, two warriors rose from the ditch in a forlorn final charge with but an empty revolver and two knives. They were quickly “riddled with bullets and fell dead.”

From start to finish, the carnage of Antelope Creek lasted perhaps three hours. The initial shooting between the soldiers and the Northern Cheyennes began at about 1 p.m., with the fighting intensifying after Company F arrived. The standoff ended at about 4 o’clock. “When the fight was over,” remembered Shangrau, “the Cheyennes fired their last cartridge.” For the people, their defensive pit had become a cauldron of dashed hopes, frustration, and loss. Of the 32 Northern Cheyennes occupying the pit defenses at Antelope Creek, total casualties numbered 18 men, five women and three children killed or died of wounds. Army losses at Antelope Creek totaled four killed and three wounded. When the shooting subsided, Captain Lawson recalled, “I saw a little girl on the opposite side of the pit looking imploringly at us. I instantly gave the order [to] cease firing and[,] leaping in onto the dead bodies[,] took the child by hand and helped her out. I also took hold of a squaw’s hand and assisted her in getting up from amongst the dead, and called on the men to assist all those that were wounded and living out of the pit.”

The fight at Antelope Creek was over, but not the Army’s prosecution of the Northern Cheyennes. The events comprising the breakout were scrutinized in formal proceedings at Fort Robinson that largely absolved that hierarchy. Eventually, the Cheyenne survivors were transferred to the New Red Cloud Indian Agency at Pine Ridge, Dakota Territory. Several faced prosecution for the misdeeds in Kansas, but were later freed and returned to Darlington Agency. Ultimately, the Northern Cheyennes at Pine Ridge were permitted to move to their new reservation in Montana, established in 1884. Because of intermarriages and other reasons, some chose to remain in South Dakota, where their descendants live today.