The president paved the way for the great Westward Expansion.

On March 4, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln took the oath of office for the second time. He had big plans for the nation as it worked its way clear of the Civil War. Those plans were placed in jeopardy when Lincoln was assassinated just 41 days later. And yet, many of those projects really took hold and made a mark after his death.

During his first term, the President had been looking West—even been thinking about his retirement. “I have long desired to see California,” said Lincoln. “The production of her gold mines has been a marvel to me, and her stand for the Union, her generous offerings to the Sanitary Commission, and her loyal representatives have endeared your people to me; and nothing would give me more pleasure than a visit to the Pacific shore…”

– Lincoln Tintype by Matthew Brady courtesy Library of Congress/Homestead Advertisement Courtesy Beinecke Library, Yale University/Sacramento Depot Courtesy Library of Congress –

Lincoln had an affinity for the West, one that he’d already established by 1865. In fact, the year 1862 was a big one for the region, at least in terms of government actions aimed at pioneering and settlement. Over a month and a half period, between May 15 and July 2, Lincoln championed and signed four measures that would forever alter the West. Historian Todd Arrington refers to them as the “Western New Deal.”

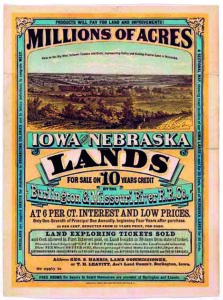

The initial two came in mid-May of 1862. The first created the Department of Agriculture and was designed to promote farming—and take ag technology and methods to the West. The second was the Homestead Act. It opened millions of acres of public lands to settlement, farming, ranching, etc., at a relatively cheap cost. It was open to pretty much everyone, not just white males, including blacks in 1868. Ultimately, homesteads reached 30 different states and covered 270 million acres.

The next two acts came in the first days of July. The Morrill Act created the land grant college system. States were given public lands in the West to sell—then they used the proceeds to start agricultural and technical colleges in their states. Counting additional acts in 1890 and 1994, there are now 102 land grant colleges/universities. Many are located in the West, providing educational opportunities for residents as well as research and other services.

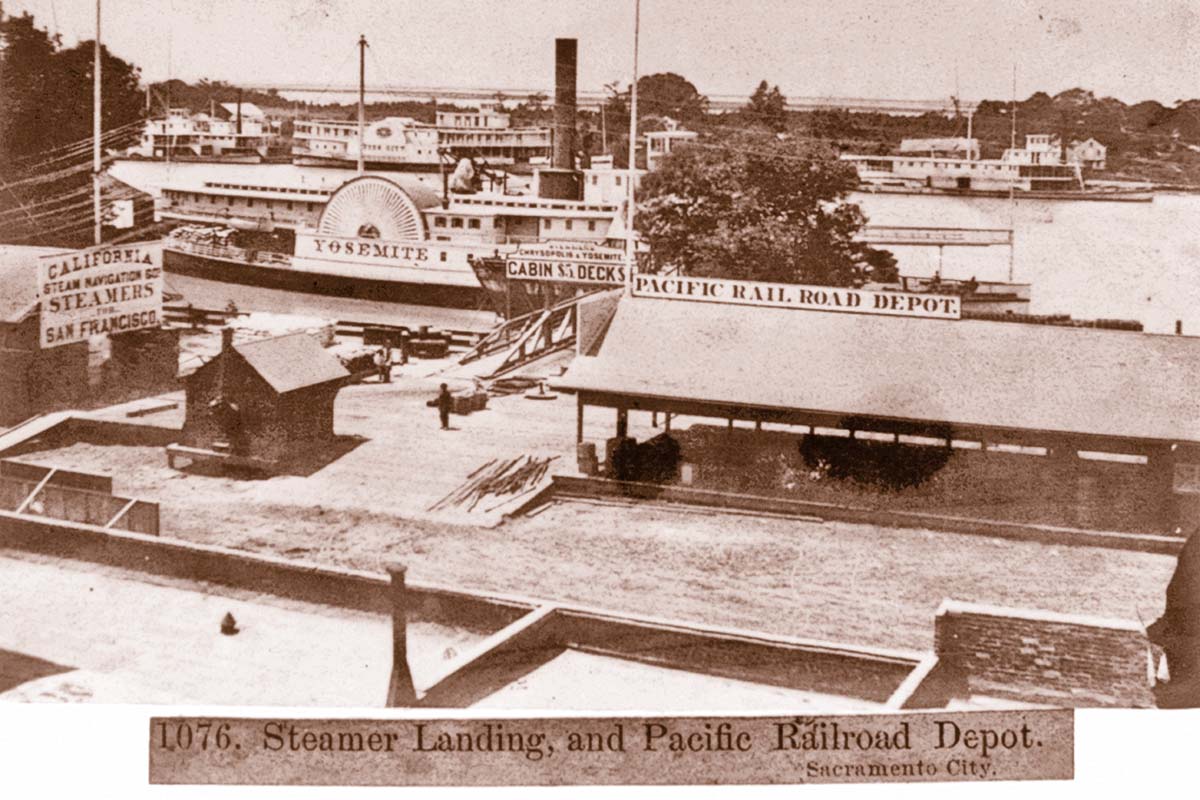

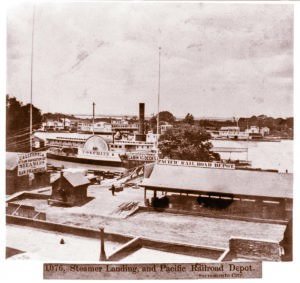

The final act may be the most important. The Pacific Railway Act created the transcontinental railroad, which would improve transportation from east to west. The railroads really opened up the West, and towns along the routes saw huge economic benefits as a result. Lincoln, by the way, made sure that the railroad ran along a northern route—which was very important during the Civil War. The project was completed in 1869, but already additional railroad projects were under construction.

While all of these became law during Lincoln’s first presidential term, sadly, he wouldn’t live long enough to see their greatest impact. In particular, he spoke of the future transcontinental railroad, of how he and his wife, Mary, would be able to take the train from Illinois to the Promised Land of California.

And if he’d made that trip, there was a special destination. On June 30, 1864, Lincoln signed the Yosemite Grant Act. It gave the Yosemite and Mariposa Big Tree Grove areas to California—with the proviso that they had to be set aside as parks. This was the first real state park in the country. And a little less than eight years later, Lincoln’s favorite general, Ulysses S. Grant—now president—made Yosemite the first national park. That set in motion land preservation that started a different kind of tourism for the West.

Even after he was gone, Abraham Lincoln’s fingerprints were all over the West, setting the stage for the region as we know it today.