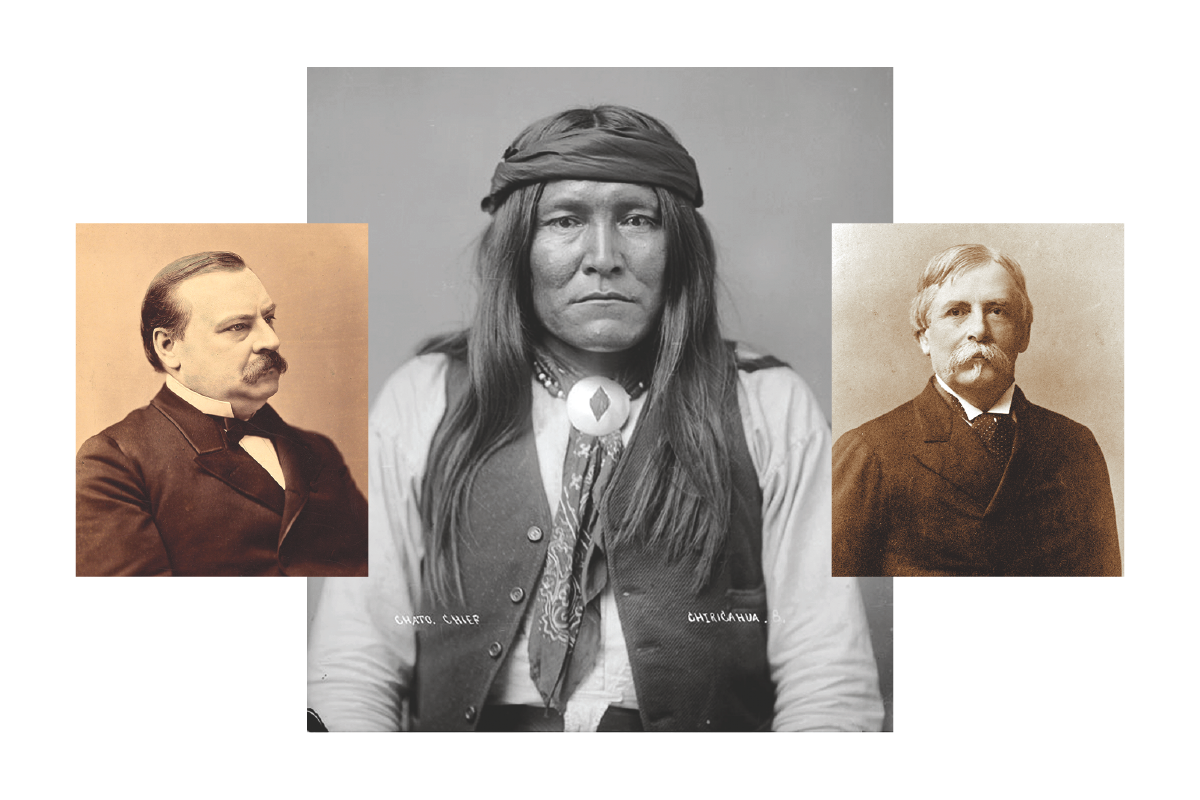

The federal government’s betrayal of Army Scout Chato is still a stain on American history.

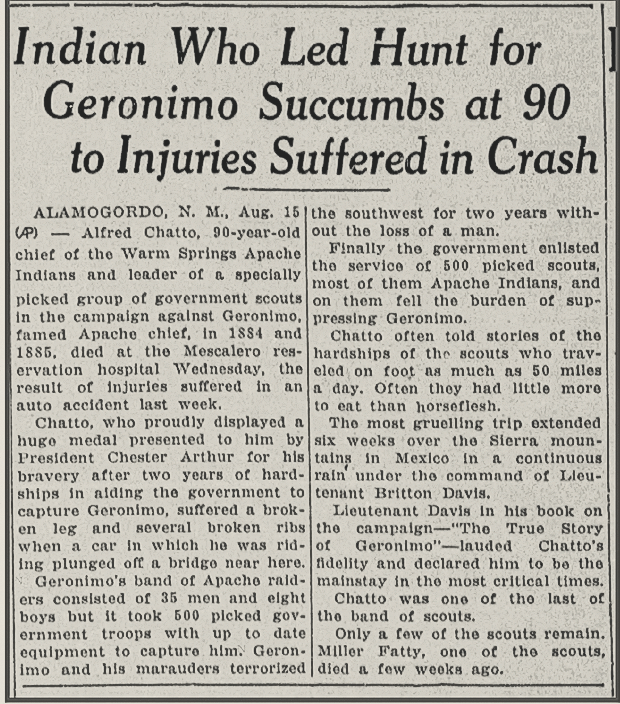

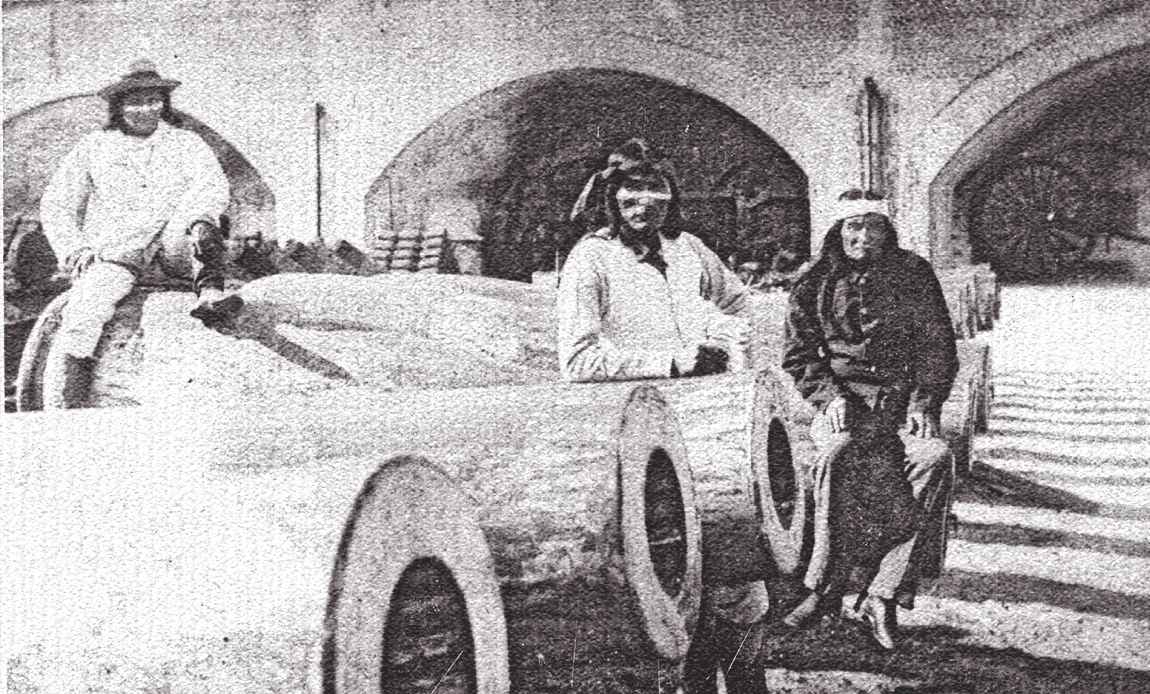

In 1934 Chato, well into his 80s, a shiny silver medal pinned to his vest, enjoyed good White Eye whiskey with his friends parked in a dilapidated old car up a Mescalero canyon out of sight of the main road. Finishing the whiskey, they let the car roll chugging and grinding out of the canyon and down main road ruts running by a creek. Despite being drunk, it was easy enough to steer the car along in the ruts until it suddenly swerved off the road, rushed down the creek bank, and landed in cold, rushing water. A passerby helped get Chato out of the car and to a doctor’s care. Pneumonia soon took him. The wind carried rumors of retribution across the Mescalero Reservation saying, “Yep, they finally got him.” There was no proof, only the knowledge that the old Apaches had very long memories and never let perceived wrongs go unavenged even if they had to wait years. The rumors soon died like the wind to light breezes of occasional whispers.

Chato outlived most of his friends and enemies, but the memories that seemed to make him a pariah at Mescalero were from his days as an Army scout and his bitter antagonism with Geronimo, once friend and ally. Their antagonism reflected the Chiricahua war and peace tribal factions that existed after the breakout of 25 percent of the Chiricahuas from Fort Apache on May 17, 1885.

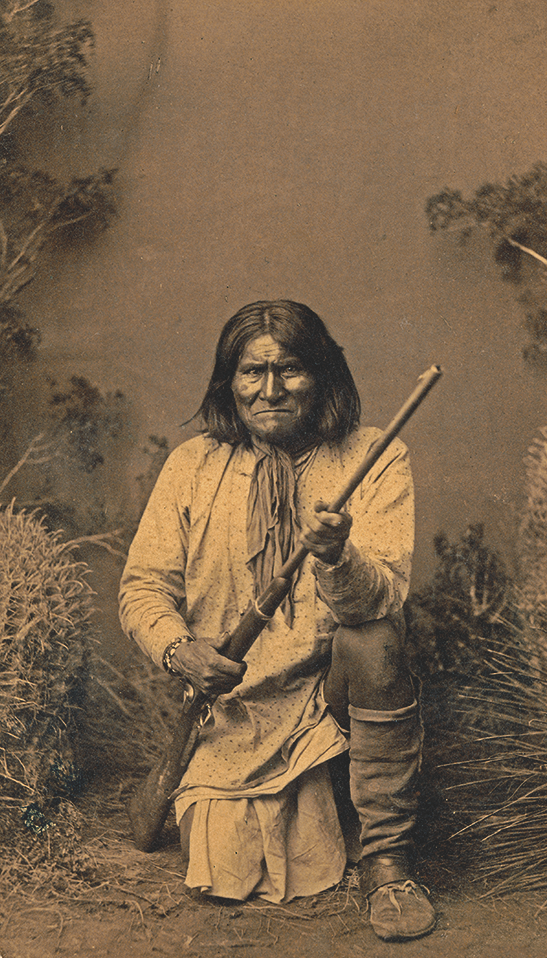

Goyahkla (Geronimo, as the Anglos called him after the Mexican nickname, “Jeronimo”), was never a chief. He was a powerful di-yen, a shaman, who, with seeming supernatural Power, could cure diseases; tell the direction of enemy approach; predict time, place and manner of future enemy attacks; and envision events at great distance when they happened. Geronimo was a consigliere to the young Chokonen Chiricahua chief, Naiche, who also made him his war leader, and he was the segundo (number two) for the indomitable Nednhi Chiricahua chief, Juh. A hard-eyed killer, Geronimo loved his People and his family, but hated disloyalty. He called Chato a traitor and at least once, told his brothers Fun and Tsisnah to kill him.

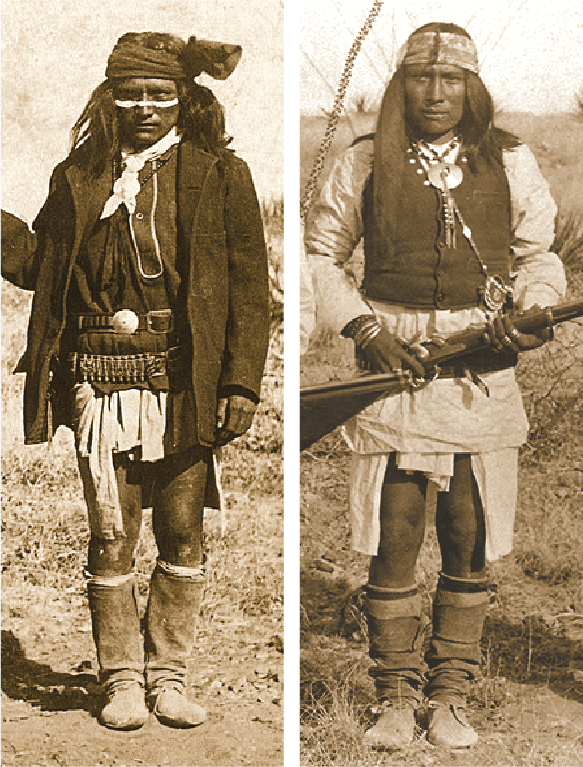

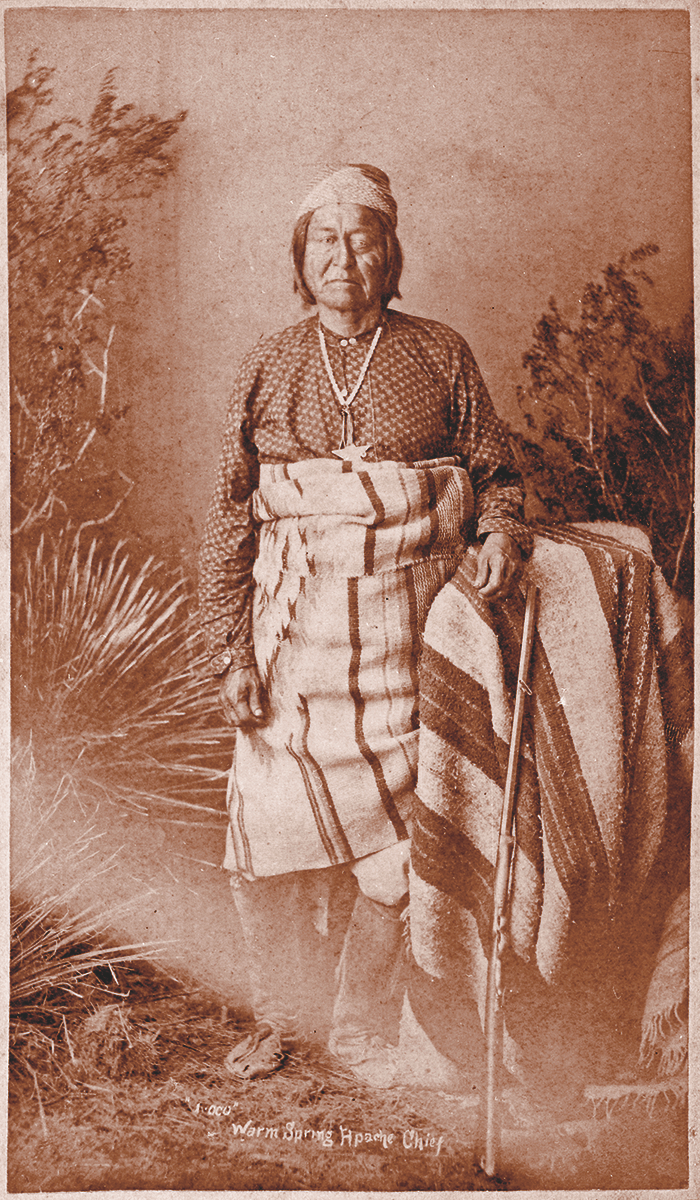

Pedes-klinje was a Chiricahua chief the Mexicans nicknamed “Chato” (flat-nosed), the name by which the Anglos also called him. Eve Ball quotes James Kaywaykla from In the Days of Victorio: “The White Eyes had no more implacable enemy than Chato. His brother had met death at their hands; and so had their father, Mochas. Chato boasted of taking many White Eye lives in retaliation.” In the late 1870s through the mid 1880s Chato led a small but powerful band of about 10 warriors and 30 women and children. He was always ready to fight and not reluctant to express his opinion in councils, even when it wasn’t wanted, which made him less than popular with other Chiricahua and Chihenne leaders. Chato said of Geronimo, “I have known Geronimo all my life and have never known anything good about him.”

Chato, 30 years younger than Geronimo, often served as his segundo in numerous raids and fights from 1877 until 1883. Along with 375 other Chiricahuas, he eagerly followed Geronimo and Juh when they left San Carlos for the Sierra Madre in late September 1881. The following year, in April 1882, Chato played a major role supporting Geronimo in abducting Loco’s 350 Chihenne (aka Warm Springs) Apaches, which included 50 fighting men, from San Carlos to Juh’s Sierra Madre stronghold. The abduction was a major success during their run toward the border, the Chiricahuas losing only one warrior in a fight with cavalry near Stein’s Peak in New Mexico. But within the span of two days, after crossing into Mexico, Loco lost more than 40 percent of his People and about half his warriors. Many Chihennes held Geronimo responsible for the loss of so many of their People and developed a long and abiding dislike for him and his supporters who had forced them from their San Carlos homes. Surprisingly, the other chiefs involved in the abduction, including Chato, received little of this animosity.

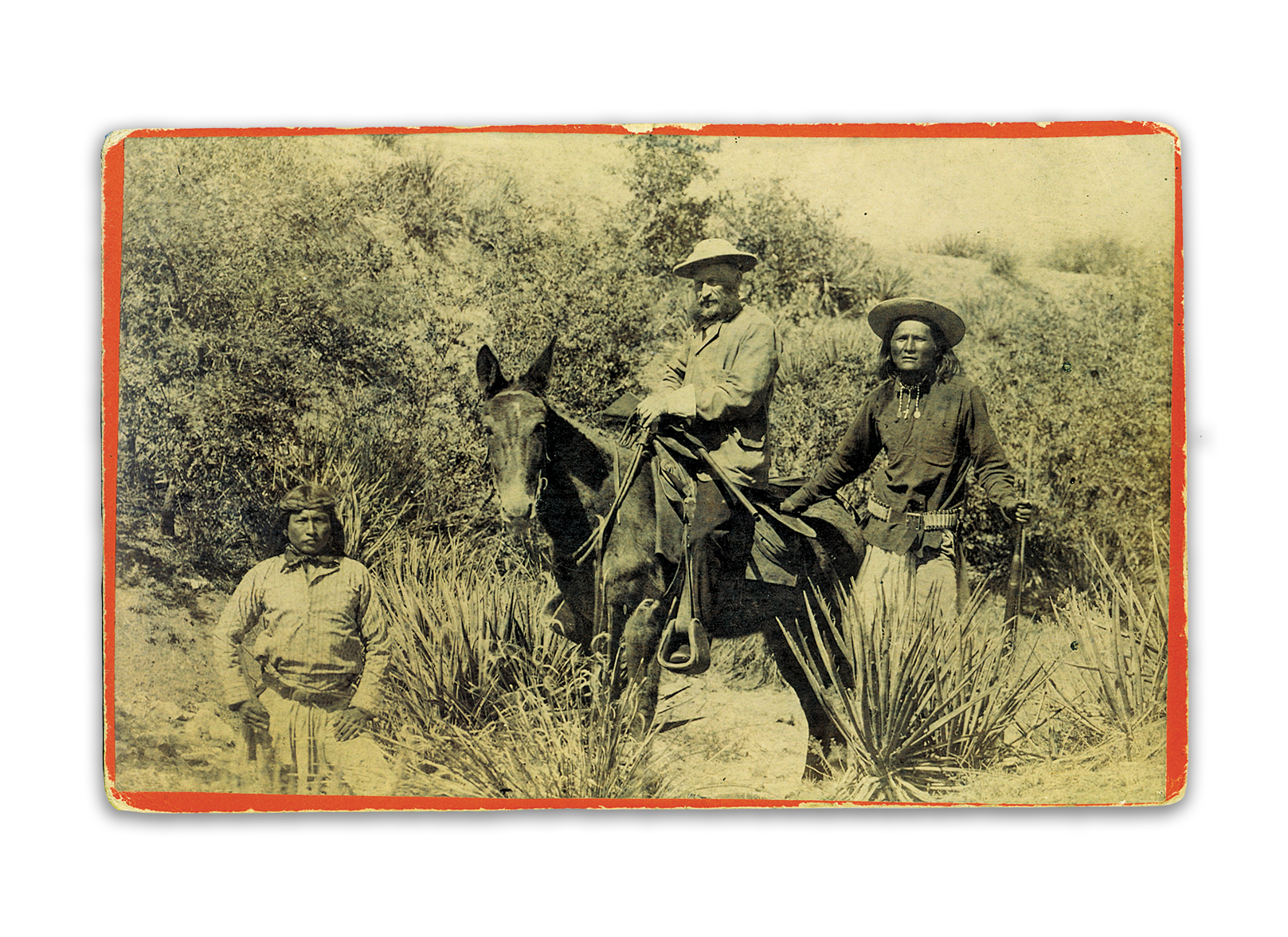

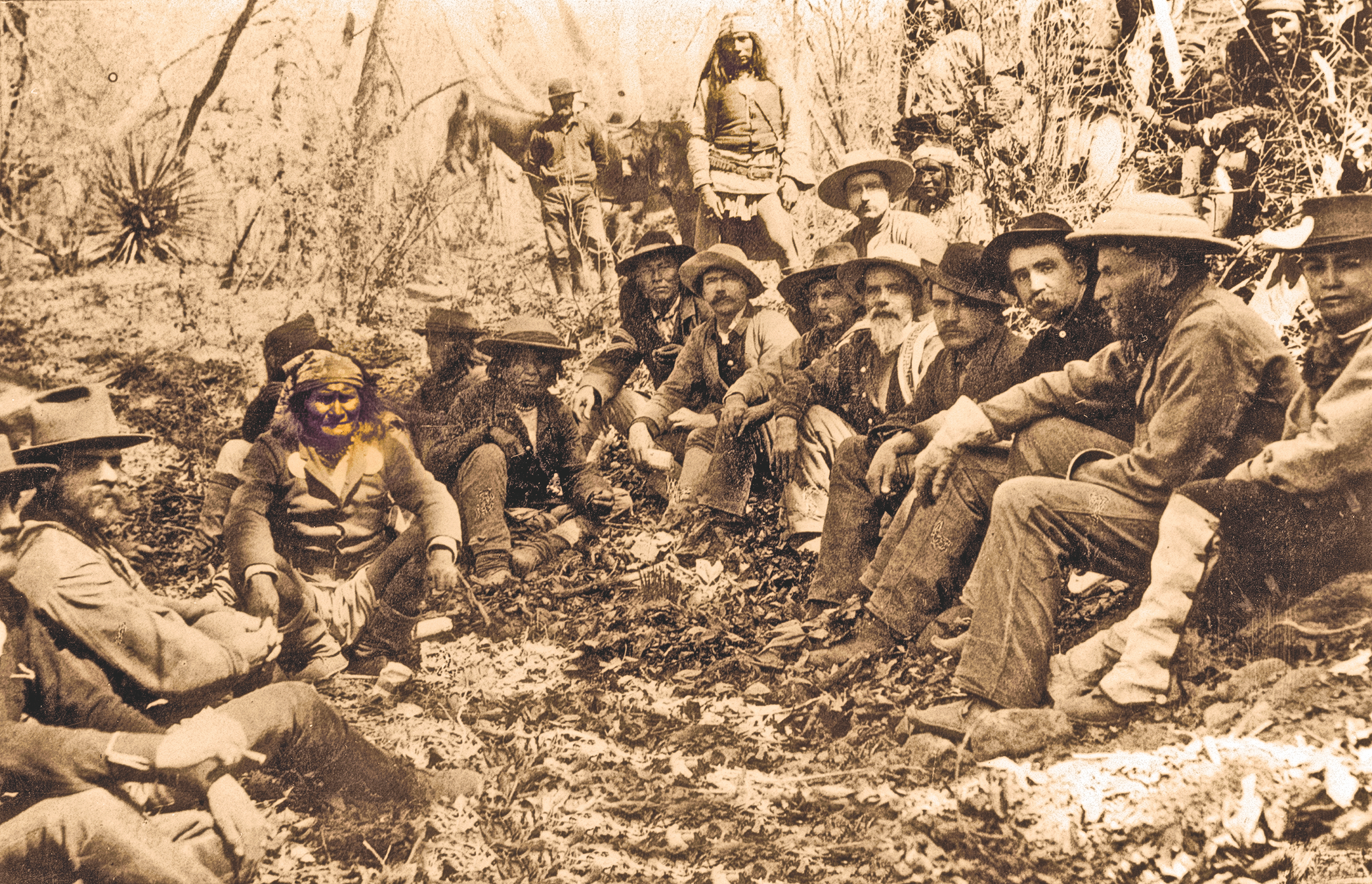

The following year, in May 1883, Gen. George Crook suddenly appeared at the camp of Chato and Bonito at Mesa Tres Ríos in Sonora (the Apaches called the area Bugatseka) with 193 Apache scouts and 50 mounted soldiers. The Apaches were stunned to see that the Mexicans let Crook cross the border, that he had found their camps, and that his primary soldiers were Army scouts, their own people. When Crook took the camp, Geronimo and Chato were at least 120 miles away leading some of their best warriors to take captives they could trade back to the Mexicans for family members who had been taken into slavery.

The same day Crook’s scouts attacked the camp with little bloodshed, Geronimo had a vision telling him Blue Coats were in their camp. The warriors raced back to Bugatseka to find the vision was true. Geronimo and the other chiefs including Chato thought Crook had god-like powers that enabled him to cross the border and find and take their camps. The chiefs and Geronimo agreed to return to San Carlos where Crook promised to give them good reservation land for their sole use and to protect them from agent theft of their rations and annuities.

Chato had a long talk with Crook at Bugatseka and decided that it was best for him and his band to accept the leadership and direction of the Army. In June, needing to get about half the People (those who had come in) to San Carlos, but running out of supplies, Crook let the chiefs stay in Mexico to gather their scattered people and then return. The last two leaders to return were Chato in early February and Geronimo in late February 1884.

General Crook gave the Chiricahuas a piece of the Fort Apache Reservation along Turkey Creek and made Lt. Britton Davis their Army commander. After they crossed the Black River in May 1884, on the way to their first camps on Turkey Creek, General Crook joined the chiefs and leading men in a council. During the council Chato pleaded with Crook to use his influence to get their people out of Mexican slavery, and Crook promised to do what he could. The promise gave Chato hope of getting his wife and children back and made him fiercely loyal to Davis and Crook.

Chato’s loyalty to Davis and Crook led him to report to Davis nearly every day on how the camps were doing and if there were any concerns among the People that Davis needed to address. The Chiricahuas knew Davis had three spies informing him about what was going on, and because Chato spoke with him almost every day, they thought Chato was a spy. He was not a spy. In fact, at that time, he wasn’t even an Army scout, but he often used his daily reports to make any rivals for tribal power look as bad as possible—at least that’s what some Chiricahuas believed.

After spending a peaceful time during the summer and fall months of 1884 on Turkey Creek and a winter at Fort Apache, the Chiricahuas returned to their camps and nascent farms on Turkey Creek. In April 1885, tensions between the Army and the Chiricahuas increased, as they had earlier in 1884, over General Crook’s rules against wife-beating and making and drinking tizwin, a strong corn beer. The Apaches considered these rules interference in their private affairs. All the Apaches, except the scouts who were led by Chato as First Sergeant, challenged Davis on the tizwin rule by getting drunk at the same time one evening in mid-May 1885. They came to his tent the next morning, some with a hangover, others still drunk, and wanted to know if he intended to lock them all up. They didn’t believe he could. Davis referred the decision to General Crook, but due to a communications snafu, Crook never got the request.

After waiting two days for Crook’s answer, Geronimo decided it was imperative to leave the reservation on May 17, 1885, before he was thrown in the guardhouse or taken to Alcatraz. He told his brothers, Fun and Tsisnah, to assassinate Davis and Chato at the next scout assembly, take all the ammunition out of Davis’s supply tent and get all the scouts they could to join them.

Late on the afternoon of May 17, 1885, Fun and Tsisnah, at the scout assembly in front of Davis’s supply tent, heard Davis tell Chato to command the scouts to “butt” their rifles (hold their rifles by the end of the barrel with the butts on the ground) and to shoot anyone who raised a rifle among the assembled scouts. They decided the assassination attempt was too risky and slipped away with two other deserters.

When Geronimo, Nana, Mangas, Naiche and Chihuahua left the Fort Apache Reservation only about 25 percent of the band was with them. The rest stayed peacefully on the reservation, minding their own business and tending their farms. It was learned later that Naiche and Chihuahua left because Geronimo had mistakenly told them that Davis and Chato had been assassinated, and they believed they would be implicated.

After leading the scouts who tracked the escaping Apaches, Davis and Chato left to return to Fort Apache, but left their scouts to support Capt. Allen Smith. Davis wanted to brief General Crook as soon as possible on the facts of the situation by wire. Chato with Bonito, both very bitter about the escape, wanted to select and organize scouts to hunt down the escapees. Seventy percent of the Chiricahua men who had stayed on the reservation would eventually serve as scouts in the search for the escapees in Mexico. For some, the work of going after friends and relatives was not pleasant, but most, with relatives they wanted out of Mexican slavery and who disliked Geronimo, were anxious to join Chato and Bonito. Their enemy had become their own people and their anger was directed at their symbolic leader, Geronimo, whose actions had threatened their livelihood on Turkey Creek and the chances of Crook getting their People out of slavery in Mexico. Their leader was Chato. Many of the Chiricahuas believed Chato had great supernatural Power, which he claimed years later came from dreams that told the future and muscle tremors that warned of immediate danger.

Chato became the trusted advisor to General Crook, Captain Crawford and Lieutenant Davis. He successfully led scouts into Mexico during the long, hot summer of 1885, forcing Geronimo and the chiefs with him to split, reunite and split again to avoid attack on their camps and capture. Weary from the cat-and-mouse struggle in Mexico, Chato and many other Chiricahua scouts didn’t reenlist in November 1885. They returned to Turkey Creek to tend to their farms.

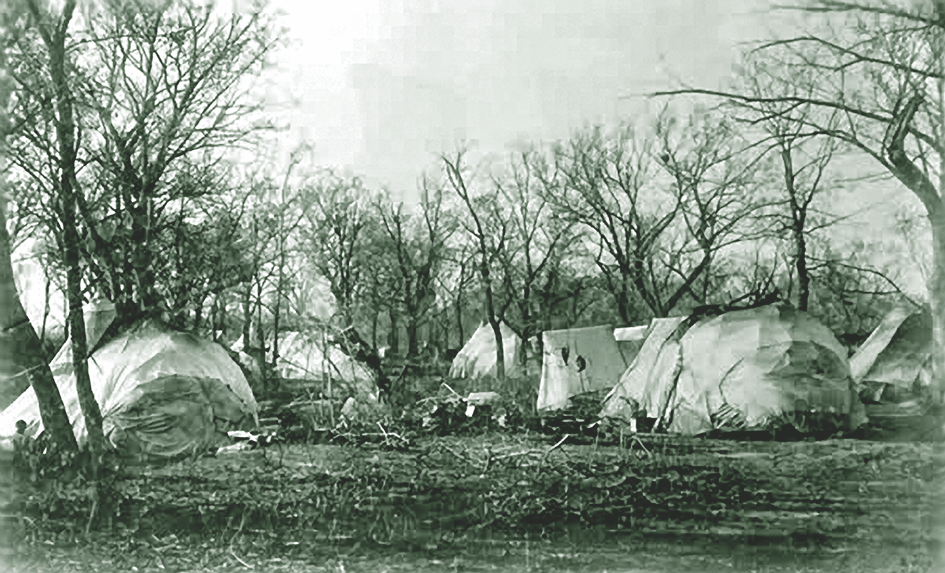

In late March 1886, the Chiricahuas surrendered to General Crook at Embudos Canyon about 10 miles south of the border, but two days later, just before they crossed the border, a band led by Geronimo and Naiche broke away from the main group and refused to surrender until late August 1886. The main group under Chihuahua was shipped as prisoners of war to Fort Marion, Florida, in April 1886.

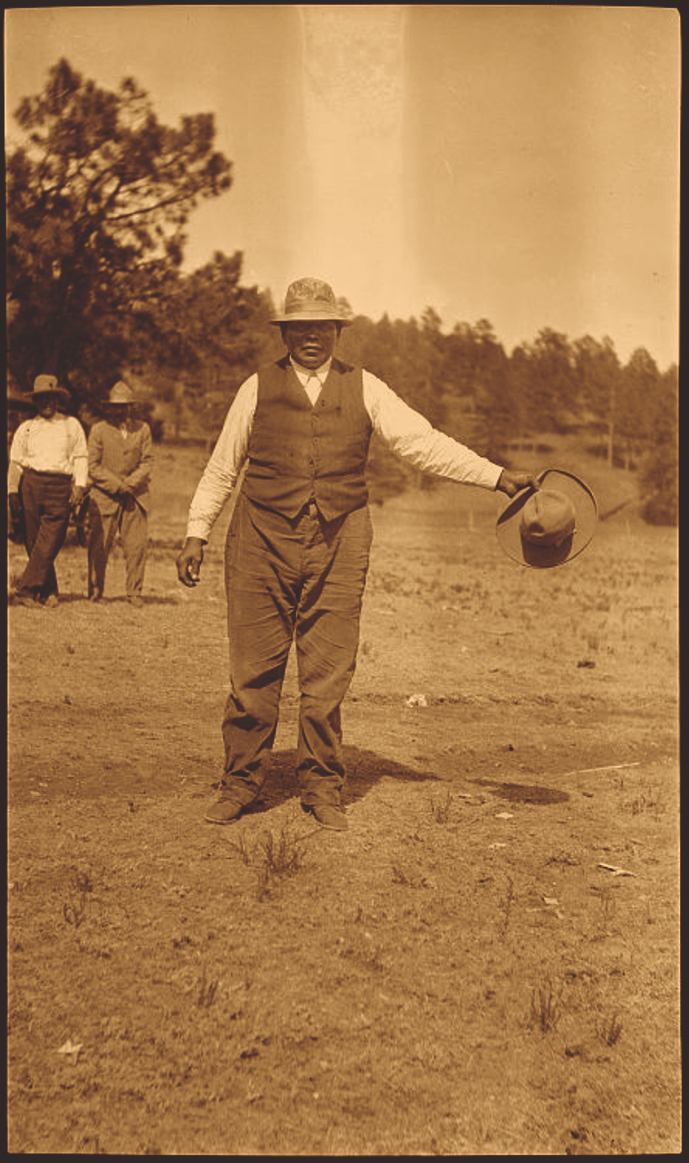

In July 1886 Chato was asked to leave his farm and lead a delegation to Washington and petition Secretary of War William C. Endicott to allow the Chiricahuas who helped the Army bring in the Chiricahua renegades to keep their land at Fort Apache. Endicott gave them a paper that they thought said they could stay at Fort Apache, but it only stated they had visited his office. President Cleveland gave Chato a fine silver medal that he wore on his vest or coat until his end of days. After the delegation boarded the train back to Arizona, in a stunning, shameful betrayal, they were delivered to Fort Marion and became prisoners of war for the next 27 years.

Geronimo and others blamed Chato for betraying the Chiricahuas to the White Eyes, but it was the White Eyes who betrayed all the scouts and innocent Chiricahuas who had lived peacefully on their farms while Geronimo and others rampaged across Sonora and Chihuahua. Chato survived the unrewarding, 27-year prisoner-of-war internment but had become a bitter old man when he was released from Fort Sill, Oklahoma, in 1913. He and his wife, Helen (who he had married at Fort Marion to save her from being shipped to the Carlisle school when she was 15), moved with other Chiricahuas to the Mescalero Reservation in New Mexico.

The factional hatred that living together as prisoners of war had kept in check finally made Chato a pariah to other Chiricahuas and many Mescaleros. Geronimo’s nephew, Asa Daklugie, a leading light for the Chiricahuas, passed on to younger generations the belief that Chato was a traitor.

In 1913 most of the Chiricahuas chose to live in the White Tail area of Mescalero. Chato chose to live with Helen alone at Apache Summit about 10 miles from the Mescalero Agency. He hauled water from the agency once a week, not an easy job for a man near 60. His death in August 1934, whether from revenge or accident, ended the life of one about whom Lt. Britton Davis wrote in 1929, “Chato is the finest man, red or white, I have ever known.”

W. Michael Farmer’s historical novels and nonfiction books on the Mescalero and Chiricahua Apaches have won Will Rogers Medallion Awards and New Mexico–Arizona Book Awards for Adventure–Drama, Historical Fiction, Literary Fiction and New Mexico History.