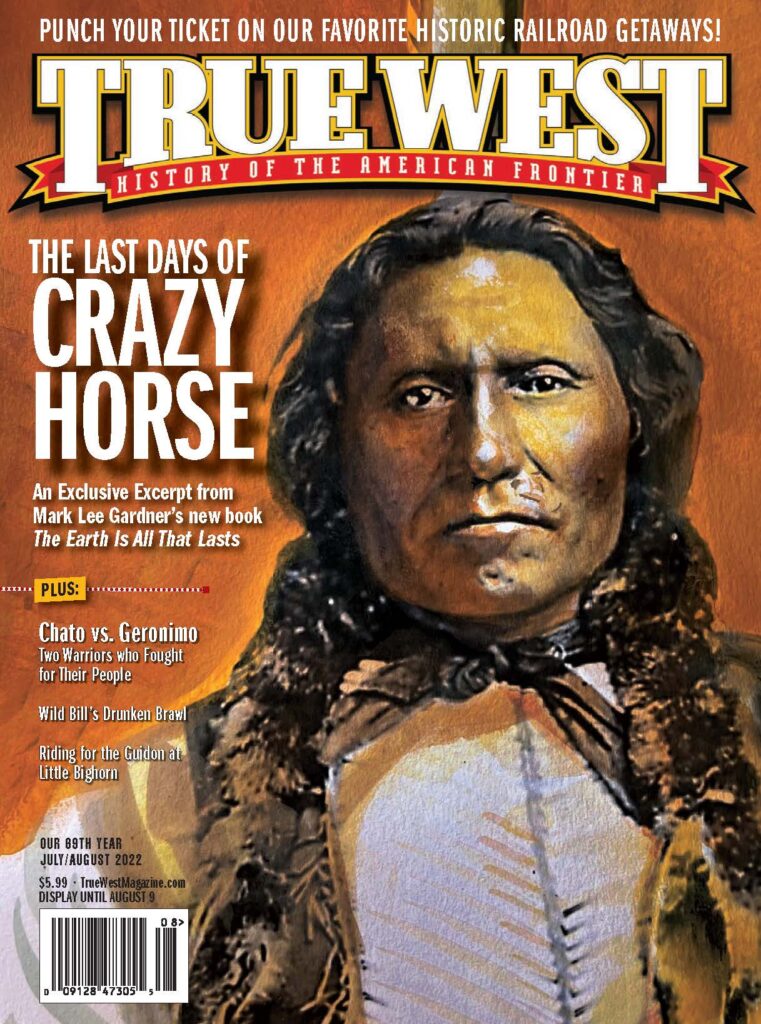

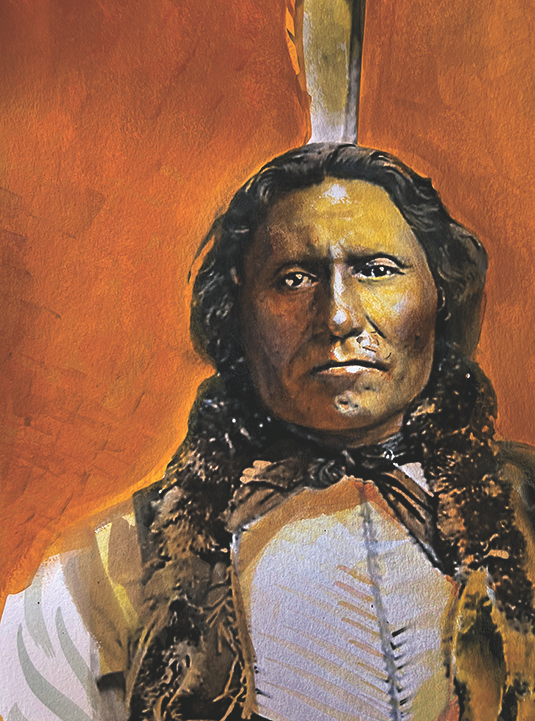

The prophetic Lakota leader’s final days still haunt us today.

There were too many tongues. Crazy Horse sought quiet on solitary walks on the prairie, away from his village. On one of these walks, he chanced upon a dead eagle, and it deeply disturbed him. Crazy Horse returned to his lodge and sat in silence for several hours. The war chief was often immersed in his own thoughts, but those close to him sensed something was different. When asked what troubled him, Crazy Horse’s answer was startling. He said he’d found his dead body on the prairie.

A short time after this incident, Crazy Horse experienced a terrifying dream. In the dream, he rode a white pony on an elevated plain. On all sides were enemies and even cannons. Crazy Horse said he was killed in this dream, but how he met his fate he didn’t know. All he knew was that he didn’t die from a bullet. For a man guided by visions and dreams, this powerful nightmare could only be a foreboding.

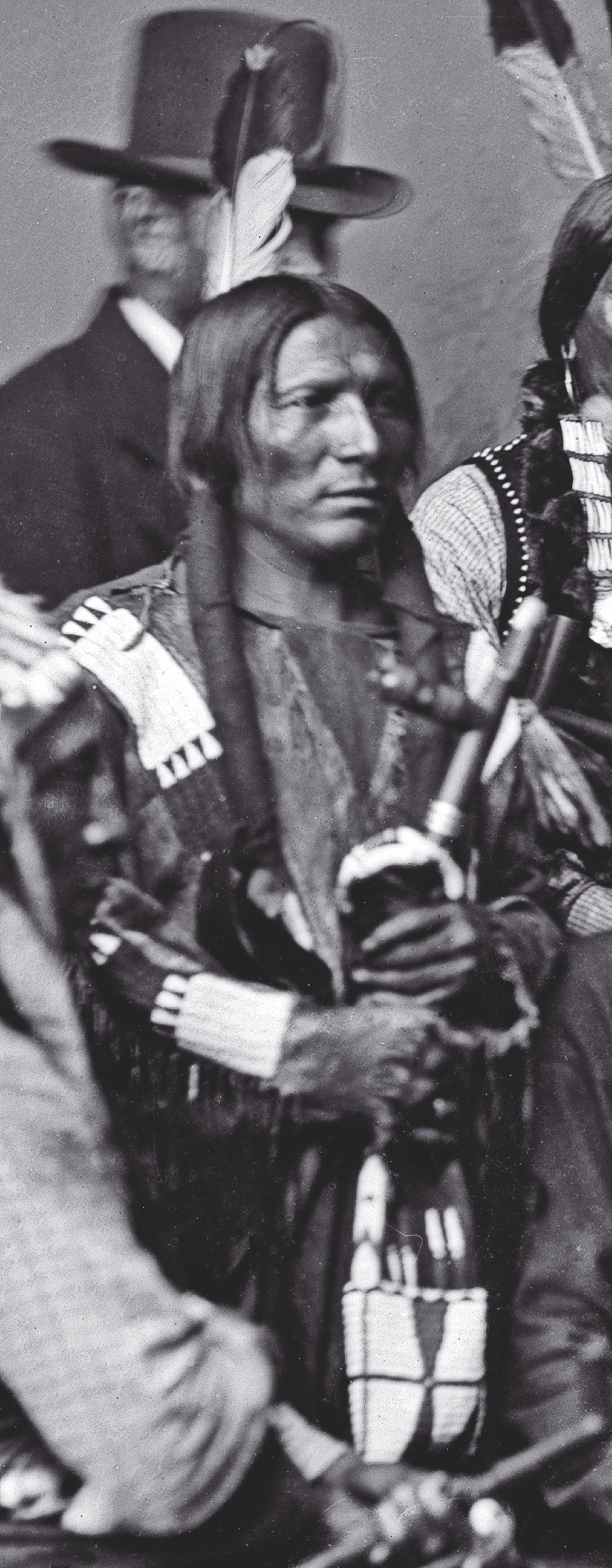

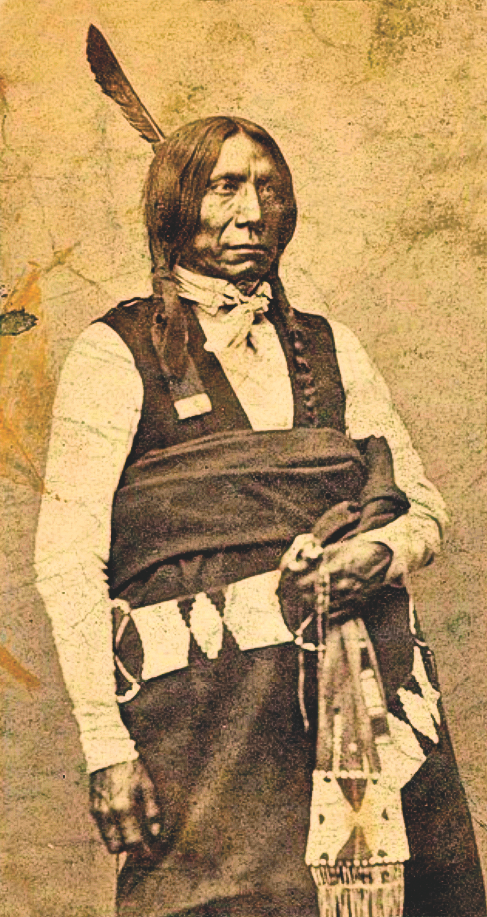

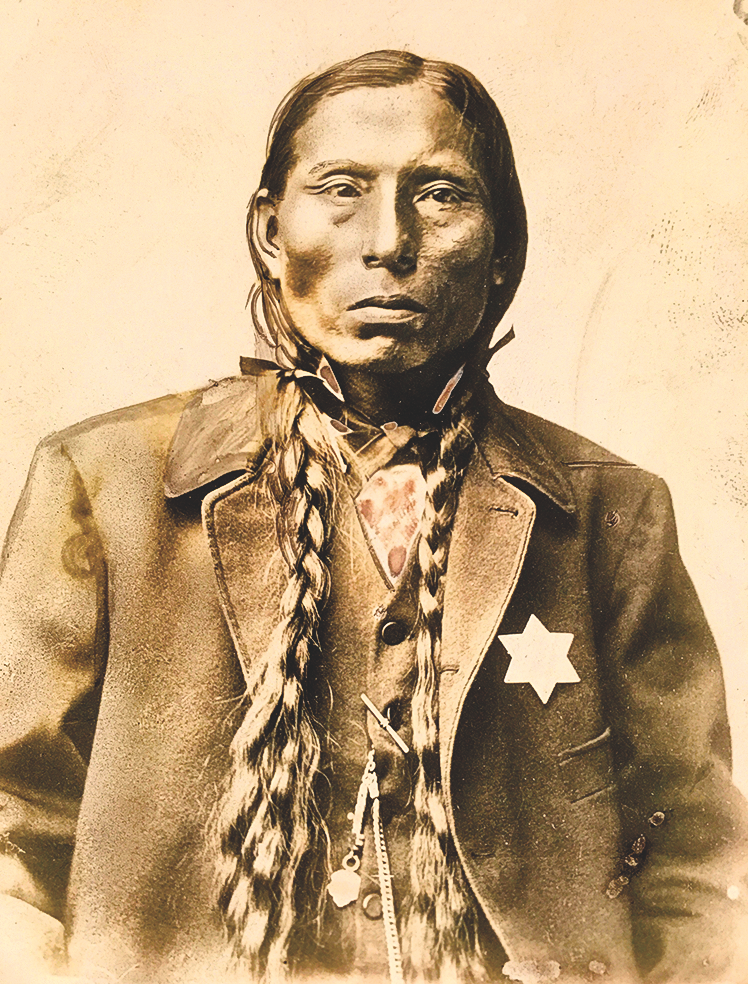

Lakota leaders like Spotted Tail, Red Cloud, American Horse, and others feared Crazy Horse because he was a threat to their status at the agencies. These chiefs believed they had a good thing going with the white man, and the last thing they wanted was a defiant Crazy Horse shaking up agency politics. Feeding their anxiety was a rumor that said the Great Father intended to make Crazy Horse chief over all the Lakotas.

All this fear put Crazy Horse in extreme danger. Many whites and Lakotas would sleep much more soundly if Crazy Horse no longer lived. When an early report from White Hat’s failed attempt to corral Crazy Horse’s band claimed the war chief had been killed, one of the officer’s wives wrote that it was “considered good news.”

Lee and Captain Burke assured Crazy Horse they meant him no harm and that he was safe at the Spotted Tail Agency. Lee was willing to consider a transfer of Crazy Horse’s band, but it was something that would have to be worked out with the authorities at the Red Cloud Agency and Camp Robinson. In the meantime, Crazy Horse would be under the protection of his friend Touch the Clouds during the night. Lee instructed Crazy Horse to report at Sheridan the following morning, when Lee would accompany the war chief back to Red Cloud to see what could be arranged. No troops would be part of the escort, Lee promised.

Fear of Trouble

Crazy Horse arrived at the post the next day as requested but informed Agent Lee he’d changed his mind about going to Red Cloud. He said he “feared some trouble would happen.” The war chief asked Lee to make the trip without him and settle the matter about the transfer. Lee made it clear, however, that that wouldn’t do. The agent stressed to Crazy Horse that no one intended to harm him and that he would have to return peaceably to Red Cloud as planned. But Crazy Horse wanted additional assurances. Accordingly, Lee promised a meeting with the Soldier Chief, Colonel Bradley, in which he would explain everything they’d discussed at Camp Sheridan. Crazy Horse would then have a chance to give his side of the events that led to his flight. If Crazy Horse was truthful, Lee would tell Bradley that he, Captain Burke, and Spotted Tail were agreeable to the transfer of Crazy Horse’s band to the Spotted Tail Agency. Lee and Crazy Horse also agreed that both would travel to Red Cloud unarmed.

Now that Crazy Horse was going to make the forty-three-mile journey, he decided he wanted a saddle; he’d ridden bareback from his village to Spotted Tail. Crazy Horse started back to Touch the Clouds’s camp to get one. Lee planned to meet him there with the ambulance. Two Sheridan Indian scouts were ordered to follow Crazy Horse to the camp. Even though Lee and Captain Burke told Crazy Horse several times not to worry about being harmed, they weren’t about to take a chance of the war chief escaping. If Crazy Horse tried to flee, the scouts were instructed to shoot his mount. If that didn’t work, they were to shoot Crazy Horse.

When the mule-drawn ambulance arrived at Touch the Clouds’s camp, Crazy Horse seemed in no hurry to leave. Eager to get going, though, was Lee, who sent the interpreter Bordeaux after the chief. But just as the interpreter found Crazy Horse, Touch the Clouds invited the war chief to his lodge for a breakfast of bread, meat, and coffee. The two friends took their time eating, seemingly trying to put off the inevitable as long as possible. Finally, having finished their leisurely meal, Crazy Horse said he was ready to go.

As promised, no troops appeared to escort the party, but a number of warriors and headmen came along, some friends of Crazy Horse whom he requested and others there to make sure the Oglala leader didn’t try to get away. Seated in the ambulance with Lee were Bordeaux, Touch the Clouds, and three other chiefs. Crazy Horse, a bright red trade blanket draped around his upper body, rode horseback.

After the procession was about fifteen miles out, it became obvious Crazy Horse wasn’t going to get away even if he’d wanted to. Small groups of scouts from Spotted Tail began to come up on their back trail. By the halfway point to Red Cloud, some forty scouts had joined the party. This sudden increase of strength had all been planned. Crazy Horse tested the escort just once by suddenly spurring his pony ahead and galloping over a rise a hundred yards away and out of sight. The scouts gave chase and brought the chief back to the ambulance. Crazy Horse said he’d only gone ahead to find water for his horse. Lee instructed him to ride behind the ambulance for the remainder of the trip. Crazy Horse now grew very serious and uneasy, more uncertain than ever as to what awaited him. This prompted Lee to reassure Crazy Horse and his friends that he would do exactly as promised, and Crazy Horse would be allowed to state his case to the Soldier Chief and request a transfer.

When within fifteen miles of Red Cloud, Lee sent a runner ahead with a message to Lieutenant Clark asking if he should bring Crazy Horse to the agency or to Camp Robinson. Lee also mentioned his promise to Crazy Horse of an audience with Colonel Bradley and asked that this be arranged. After going another eleven miles, a rider delivered Clark’s written response: take Crazy Horse directly to the adjutant’s office at the post. Clark said not a word about the requested meeting with the colonel, and as the adjutant’s office was next to the post guardhouse, Lee figure that was where Crazy Horse was going to end up. Lee still hoped for a brief talk with Bradley, however; he’d given Crazy Horse his word.

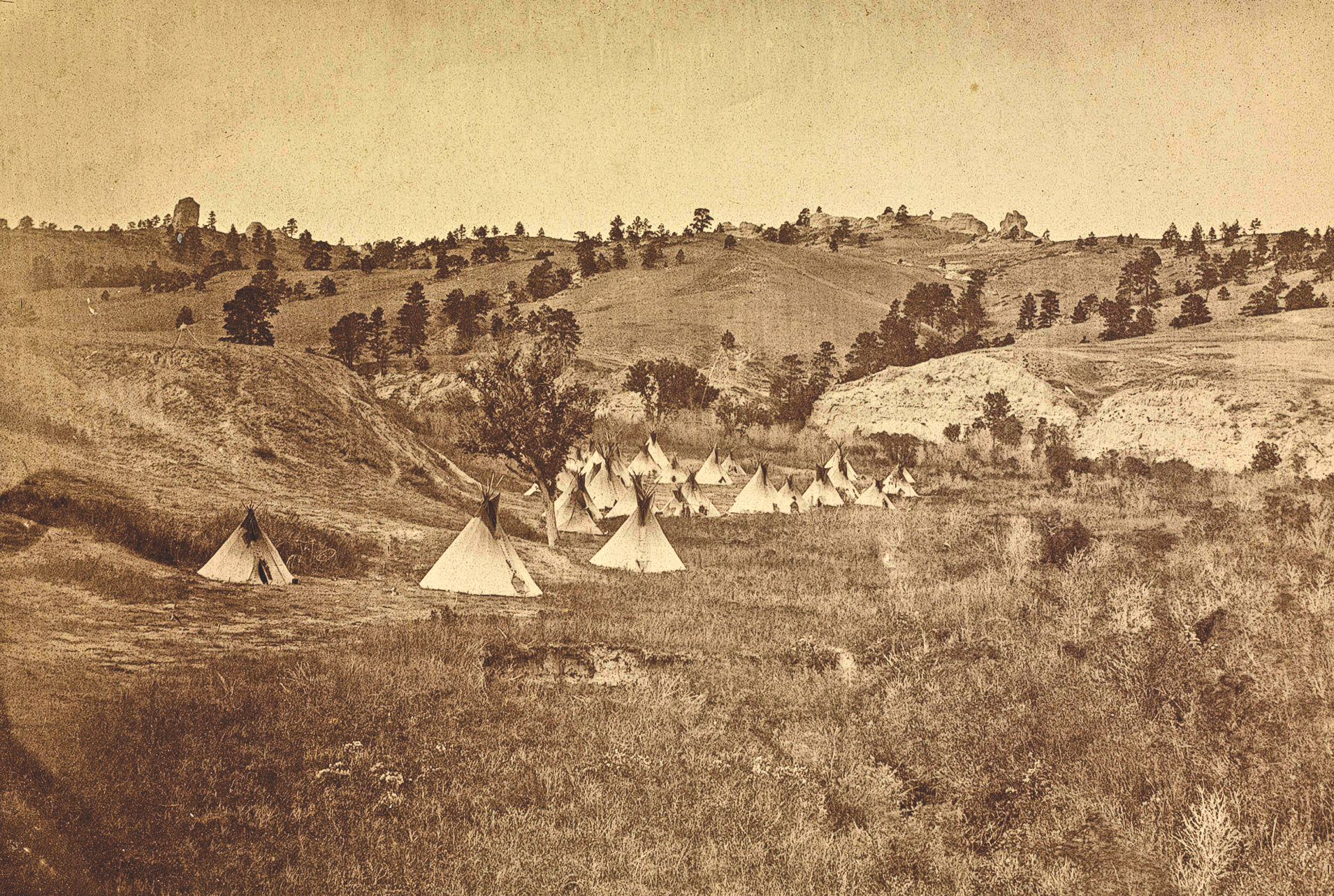

The procession passed the Red Cloud Agency at a good clip. Groups of Indians stood silently near their lodges to catch a glimpse of Crazy Horse as he passed. They’d been warned not to approach the party; it could be confused as a rescue attempt. The Indian scouts were already on edge, leery of a possible ambush from Crazy Horse’s people. A mile and a half more and the column pulled into Robinson. The time was approximately 6:00 p.m.; in a little more than an hour, sunset would bring a close to this crisp, clear day.

Alerted to the war chief’s approach, a crowd of several hundred had gathered at the post: Crazy Horse’s people, agency Lakotas, Cheyennes, Arapahos, and Bluecoats. Crazy Horse rode in front of the ambulance as it crossed the parade ground. Among those waiting to see the war chief was He Dog, who rode up on the left side of Crazy Horse and shook hands. He Dog leaned close to his friend. “Look out,” he whispered, “watch your step. You are going into a dangerous place.”

The Betrayal

The ambulance stopped in front of the adjutant’s office, on the south side of the parade ground. Here several artillery pieces were arranged in a line, not unlike in Crazy Horse’s dream. As Lee stepped down from the vehicle, the post adjutant met him and said Crazy Horse was to be turned over to the officer of the day. This meant the guardhouse for the chief. “No, not yet!” Lee blurted out. He requested that Crazy Horse be allowed to speak to Colonel Bradley first. Only the colonel could decide that, the adjutant replied, so Lee had Crazy Horse dismount and go into the adjutant’s office to wait. Crazy Horse was joined by his friends Touch the Clouds, High Bear, and other Lakotas who’d made the journey from Spotted Tail.

Lee rapidly walked the 175 yards across the parade ground to Bradley’s quarters, passing through throngs of Lakotas on horseback and on foot, all wondering what was transpiring with Crazy Horse. But to Lee’s utter dismay, Bradley refused to see the chief. General Crook, who’d departed Robinson the morning previous, had telegraphed orders to send Crazy Horse under guard to Omaha. From there, the chief was destined for exile at Fort Marion, Florida, the War Department’s prison of choice for American Indians who dared resist the loss of their lands and freedom.

Lee tried to delicately reason with his superior, explaining that the only way he’d been able to convince the Oglala leader to come was by promising he could have a hearing before the Soldier Chief. But Bradley was unsympathetic and firmly told Lee it was too late for any talk. Orders were orders. Turn Crazy Horse over to the officer of the day, he said, and tell the chief “not a hair of his head should be harmed.” Desirous of somehow finding a way to honor his pledge to Crazy Horse, Lieutenant Lee asked the colonel if it would be possible to meet with the chief in the morning. Bradley gave Lee a glance that signaled their talk was over.

This was a disconcerting turn of events for Lee; he’d betrayed Crazy Horse’s trust. Nevertheless, a promise to an Indian, one his fellow officers considered a troublemaker and a murderer, definitely wasn’t worth risking his career over. Lee walked back to the adjutant’s office and told Bordeaux to bring out a few of Crazy Horse’s friends. Through the interpreter, Lee told them he’d done all he could for Crazy Horse and that Colonel Bradley would take care of him for the night. Then Lee, who wished to avoid any uncomfortable questions from Crazy Horse, told Bordeaux to go in and tell the Oglala leader that night was coming, and thus it was too late to talk to the Soldier Chief. Instead, he was to go with the officer of the day, Captain James Kennington, who would get him settled and keep him from any harm.

Crazy Horse appeared satisfied with Bordeaux’s words and walked out with Kennington, followed by the Lakotas who’d been waiting with him. Suddenly appearing near the door was Little Big Man, who roughly took Crazy Horse by the left arm. “So you are the brave man,” he sneered. “Come on, you coward.” Crazy Horse was both astonished and taken aback. Little Big Man had seized this moment when Crazy Horse was at his most vulnerable to demonstrate how big a friend he was to the white man. Two soldiers of the guard followed close behind the war chief. Several Indian scouts watched with weapons at the ready. A distance of sixty feet separated the adjutant’s office from the guardhouse. Like many structures at the post, both buildings were constructed of pine logs. The guardhouse, one story high, contained two rooms, and from the outside, there was little to suggest its purpose. Its main door opened into the guardroom; to the right was the prison room, and it currently held a number of inmates, the chains of their leg irons clinking and rattling on the wood floor every time the men moved.

Crazy Horse stepped through the door of the guardhouse with Kennington and Little Big Man, followed by a cluster of allies, among whom were Touch the Clouds and Horn Chips, Crazy Horse’s friend and holy man. Neither Crazy Horse nor his friends realized what they were walking into until Touch the Clouds heard the sound of the chains and saw the door to the prison room with its barred window. In a startled voice, Touch the Clouds said the place was a jail. Crazy Horse instantly sprang back, careening into bodies of guards and Indians. Even though the war chief had promised Lee he would not come armed, he wore a revolver and a knife beneath his blanket. In a blur of movement, he yanked his knife from its sheath. Seeing a knife on Little Big Man’s belt, he seized that, too, and began slashing wildly in all directions while moving toward the outside doorway.

Kennington drew his saber. Little Big Man grabbed one of Crazy Horse’s arms. “Let me go! Let me go! Let me go!” the chief shouted. Stunned onlookers in the parade ground saw flashes of polished steel and heard sounds of chaos: shouts, stomping feet, chairs tumbling. Crazy Horse spun around so his back faced the doorway and lunged for the outside, dragging Little Big Man with him. Several Indian scouts raised their revolvers, causing Kennington to yell, “Don’t shoot! Don’t shoot!”

Crazy Horse brought the sharp blade of his knife down on Little Big Man’s hand, cutting deeply into his thumb and forefinger Little Big Man howled in pain and jerked his hand back, blood spurting from the wound. Indian scouts and guards grappled with the chief, who violently pulled in all directions, trying to break free. Kennington hovered near the frenzied mass of bodies looking for an opportunity to deal a blow with his saber, yelling, “Kill the son of a bitch! Kill the son of a bitch!”

A sentry next to the door, intently watching the scuffle, already had his Springfield rifle lowered, an eighteen-inch bayonet blade affixed to the gun’s muzzle. He swiftly guided the sharp point of the bayonet between those struggling with the chief and made a sudden jab, pushing the triangular steel blade deep into Crazy Horse’s abdomen, just above the hip. Crazy Horse stiffened for an instant and gasped as the sentry withdrew the blade. “Let me go, you’ve got me hurt now,” he cried. The sentry thrust again but missed the squirming chief and struck the doorframe, the rigid bayonet sinking deep into the pine wood. The soldier jerked the Springfield back to make another stab, accidentally slamming the butt of the gun into Horn Chips, dislocating the holy man’s shoulder.

Nauseated from pain, Crazy Horse stopped fighting and sank to the ground. An Indian scout grabbed the grip of the war chief’s revolver and jerked it out of its scabbard; Crazy Horse had never tried to use it. The scout held the gun triumphantly in the air. As the Indian scouts and guards stepped back from the war chief, Crazy Horse was seen to be writhing on the ground in a fetal position, moaning loudly. Crazy Horse’s father, Worm, had watched in horror as his son fought with Little Big Man and the soldiers. He now jumped off his pony and ran toward Captain Kennington, a cocked revolver in one hand and a bow and arrows in the other. The Indian scouts knocked the old man down and disarmed him. Doctor McGillycuddy also witnessed the melee, and he pushed his way through to Crazy Horse’s side. The war chief was frothing at the mouth, and his pulse in both arms was weak and intermittent.

The doctor searched for the wound and found it on Crazy Horse’s right side, where blood trickled from a small puncture on the upper edge of the war chief’s hip. The entry wound didn’t look bad, but the doctor assumed the bayonet’s long blade had traversed the entire width of Crazy Horse’s body, slicing through vital organs and causing internal bleeding. The Oglala leader had but a short time to live.

Meanwhile, Crazy Horse’s friends and followers in the crowd began shouting angrily and brandishing their weapons. The Indian scouts fled across the parade ground to the front of Colonel Bradley’s quarters. Kennington ordered his guards to take Crazy Horse back inside the guardhouse, but when they attempted to pick up the wounded chief, the crowd became more threatening, chambering rounds and cocking hammers. At this point, the interpreters Bordeaux, Billy Garnett, and Frank Grouard decided to make themselves scarce. Kennington and McGillycuddy became increasingly anxious and uncertain as what to do, neither one being able to speak or understand Lakota. All it would take was one gun going off to commence an all-out firefight.

After several tense moments, a mixed-blood Lakota offered to translate and informed the crowd that McGillycuddy wanted to move Crazy Horse inside the guardhouse so he could be treated. “Don’t take him in the guardhouse,” someone shouted, “he is a chief.”

“What shall I do with him?” said McGillycuddy.

Several in the crowd motioned to the adjutant’s office. “Take him there,” they said.

Crazy Horse was carefully removed to the adjutant’s office and placed on a pallet of blankets on the floor. McGillycuddy made a more thorough examination of Crazy Horse’s wound, confirming his earlier assessment. The doctor gave the war chief a hypodermic injection of morphine to ease his pain and bandaged the swollen puncture on his side. Touch the Clouds and Crazy Horse’s father were allowed to stay with the chief. Others in the room included post surgeon Charles E. Munn, Captain Kennington, and officer of the guard Lieutenant Henry R. Lemly. Louis Bordeaux had gotten over his fright and was there for the next few hours as interpreter.

As darkness settled on Camp Robinson, the crowd of Indians gradually melted away. Most didn’t know exactly how Crazy Horse had been hurt, whether it was from a knife or a bayonet. And they didn’t know the culprit, either. The bayonet thrust had been so quick that very few saw it, and the soldier who skewered the war chief was immediately relieved by a new sentry. Some strongly suspected Little Big Man stabbed Crazy Horse to gain favor with the Long Knives. Another theory was that Crazy Horse stabbed himself. This fantastical theory involved Little Big Man, too, for he claimed afterward that when Crazy Horse cut his hand, the blade glanced off and entered the war chief’s body. The Crazy Horse-killed-himself scenario was especially liked by White Hat. He telegraphed General Crook that he was “trying to persuade all [the] Indians” that was indeed what happened.

Under the warm glow of kerosene lamps, Crazy Horse slipped in and out of consciousness. McGillycuddy shot morphine into the war chief’s veins as needed. Lucid moments were far apart and brief. During one of these, Crazy Horse told Bordeaux the soldiers shouldn’t have stabbed him. “I had no desire to do injury to any of them,” he said. “The only man to whom I wished to do harm was Little Big Man, for his insolent treatment of me, but he got away. I don’t know why they stabbed me.”

Worm sat on the floor next to his son. Crazy Horse looked up at him and said, “Father, it is no use to depend upon me; I am going to die.” Worm and Touch the Clouds began to sob uncontrollably.

Late in the evening, about 11:00 p.m., “Big Bat” Pourier relieved Bordeaux as interpreter so Bordeaux could get some rest. Crazy Horse’s face had become very pale, and his body was growing cold. The war chief, as if speaking from a dream, began a sort of chant: “Father, I want to see you.” He repeated this several times. It was the last that Crazy Horse’s voice was heard in this world. He died at approximately 11:40 p.m. Touch the Clouds pulled Crazy Horse’s blanket over his face and pointed to his body. “There lies his lodge,” he said. The Miniconjou then motioned toward the heavens and said, “The chief has gone above.”

Crazy Horse, Tasunke Witko, was with the Thunder Beings.

“Crazy Horse’s Final Vision: The prophetic Lakota leader’s final days still haunt us today” by Mark Lee Gardner is excerpted from Chapter 12, “Father, I Want to See You,” of his latest book The Earth Is All That Lasts (Mariner/HarperCollins). Gardner is the award-winning author of nine books. A review of Gardner’s dual biography can be read in this issue’s Western Books article.

Photograph by Mark Lee Gardner

True West Archives