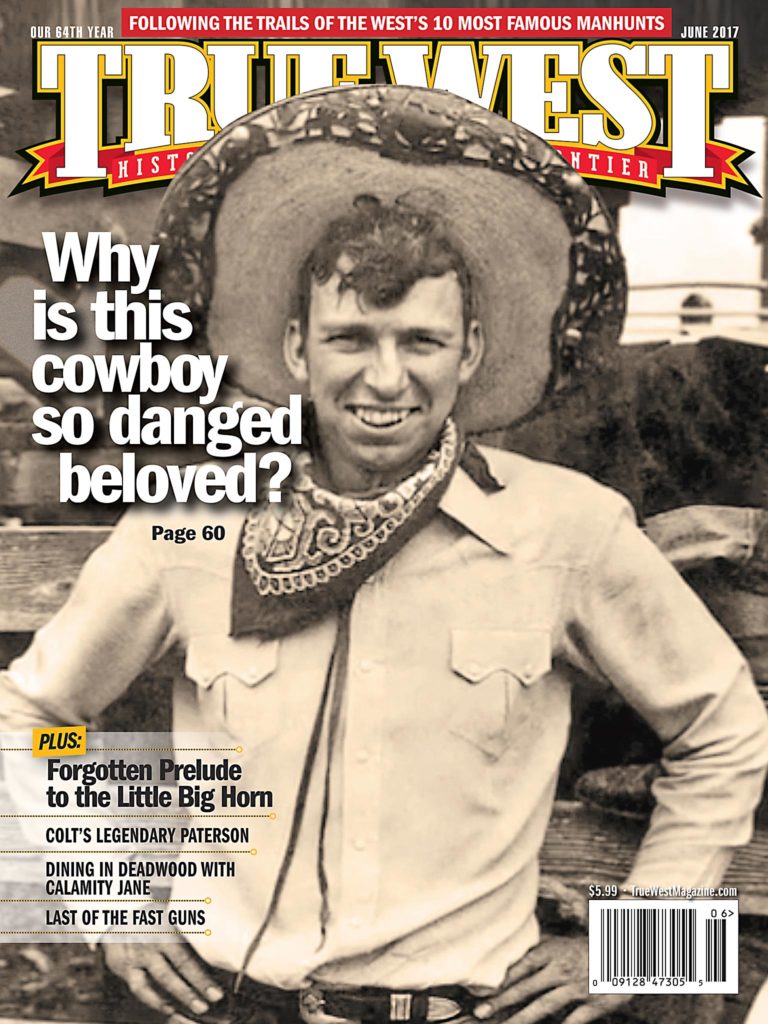

Before arriving in Tombstone the Reverend Endicott Peabody of Boston had attended school in England where he was an outstanding athlete. He graduated from Trinity College at Cambridge in 1880 then returned to the United States where he entered a three-year program to train as a minister. He left after only three months to accept a job to re-establish an Episcopal Church in Tombstone. His friends liked to say the town’s notorious reputation and foreboding name provided enough inspiration for the venturesome lad to go forth into the wilderness after only three months training.

He might have had a formal Eastern upbringing but he quickly won the respect of Tombstone society in which he mingled freely. He was also a first-class boxer and of all the sporting events staged in a typical mining camp, pugilism was the one that garnered the most respect from the miners. Not only was this proper Bostonian the kind of man who was not too uppity to drink a bottle of beer in public with the common working man, he could handle his fist with the best of them. More than once he duked it out in the boxing ring and he never lost a match. One time he was matched the local Methodist minister, “Mac” McIntyre, who was considered a pretty good pugilist. Peabody handed his rival a sound threshing. He also handedly defeated the local miner’s champion, something that made him the undisputed hero of the town.

The Tombstone Nugget wrote: “Talk about muscular Christianity, we overheard a miner yesterday say, upon having the Episcopal minister pointed out to him, ‘Well, if that lad’s argument was a hammer and religion a drill, he’d knock a hole in the hanging wall of skepticism.’”

One Sunday he preached a sermon on the Eleventh Commandment: Thou Shalt Not Covet Thy Neighbor’s Cattle” A cowboy who happened to be a well-known cattle thief took umbrage at the newcomer’s remarks and threatened to “tar and feather” the new preacher. Peabody suggested if they were going to make a fight of it they should build a boxing ring and charge admission, the money going to the local children’s orphanage. A large crowd gathered for the event and for three rounds the cowboy came at the preacher with fists flying but none of his windmill punches landed as Peabody backpedaled around the ring. Finally, the cowboy was plum worn out and dropped his arms. Peabody then delivered a round house blow the laid him out cold. The young minister had gained a whole new respect from the rough and ready Tombstonians and the attendance at the Episcopal Church kept increasing.

Billy Claiborne, a self-styled “Billy the Kid,” who was, in reality an ignominious member of the Cow-boy or rustler element, is best-remembered by western historians as the brash young man who talked tough, then high-tailed it for cover when the shooting started at the gunfight near the OK Corral leaving three of his friends to die.

Billy usually hung out in the town of Charleston a few miles west of Tombstone and a raucous burg that made the latter seem tame in comparison. When word reached him that Peabody had made another of his Eleventh Commandment sermons in Charleston he sent word that the next time Peabody set foot in Charleston he would attend and make the preacher “dance” to the music of his roaring six-gun. Peabody sent word that he would be in Charleston in two weeks and would look forward to dancing with Billy. “Billy the Kid” failed to keep the appointment.

Tombstone gladly embraced the young minister but his notes tell of how much he missed his home in Massachusetts. Unfortunately Peabody didn’t remain long, returning to Boston on July 17th, six months after his arrival. Parson noted in his diary, “It will not be easy to fill Peabody’s place.”

He returned to the Episcopal Theological School, graduating in 1884. The following year he was ordained and took a wife. He then decided to combine the ministry with teaching and with financial aid from the folks in Boston he established the famed boys’ prep school at Groton. His stated mission was to prepare young men, not for college but for life. One of his students was a bright young man from New York named Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He later officiated his former pupil’s wedding to Eleanor.

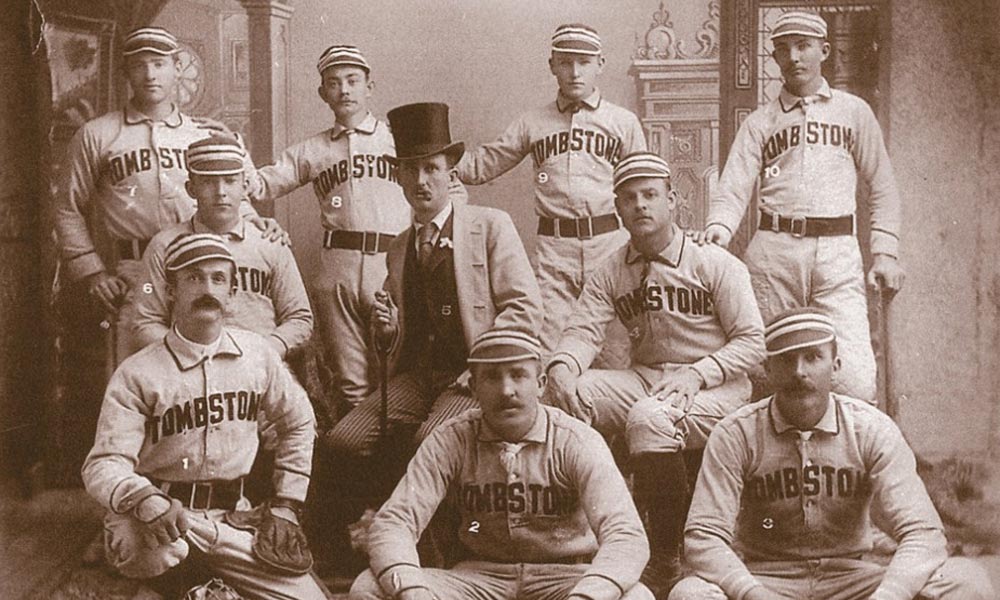

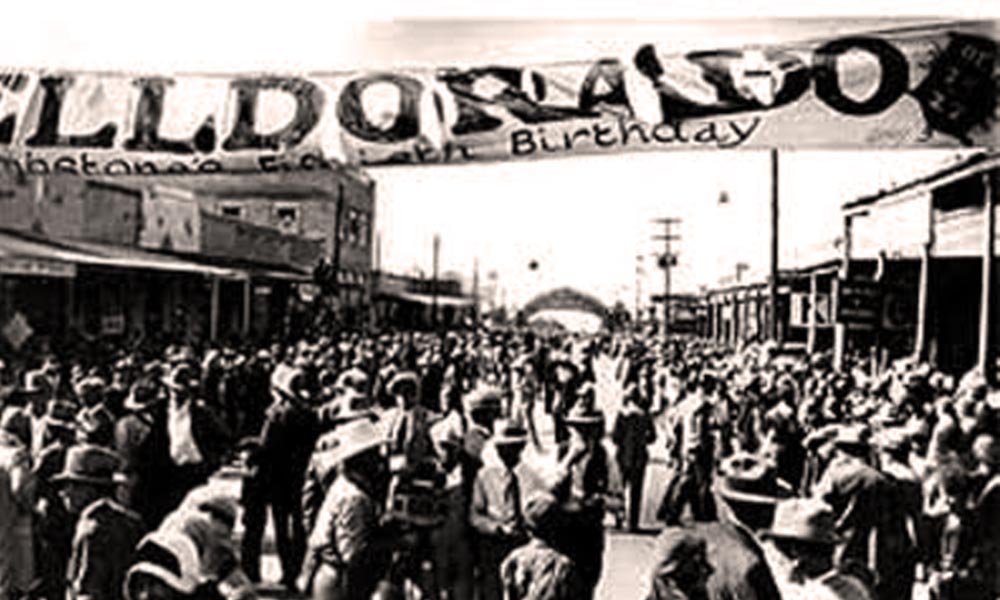

After Peabody left Tombstone the legend of the “two-fisted” preacher grew, much like that of the legendary gunfighters of the Old West. He found many parts of the myth were hard to dispel. It’s likely the overflowing crowds that attended church were attracted more by the charisma of the man than a desire for religious learning. For whatever reasons, they never forgot him. When the “two-fisted” parson returned to the “Town Too Tough to Die” to preach a sermon in 1921 and again in 1941 his old flock traveled from all over the state to be present for the occasion.

Tombstone also left its lasting effect on Peabody as well; the generosity, independence, rugged individualism and honest determination he observed there. Years later he wrote of these people: “They could almost fairly be so described (the good old days in Tombstone) for they helped one discover the ideals and generosity which are latent in our people….It has taught me that in America we are all just ‘folks.’”

In 2007, following the 125th anniversary of the building of the St. Paul’s, Peabody was added to the Episcopal Church’s liturgical calendar, with November 17th becoming the feast day of Endicott Peabody. He is thus regarded as the “patron saint” of the Episcopal Diocese of Arizona and venerated as one of its most important missionaries.

The Peabody’s are one of Massachusetts’ most illustrious old families dating back to Colonial times. His son Malcomb E. Peabody, was Episcopal Bishop of Central New York.

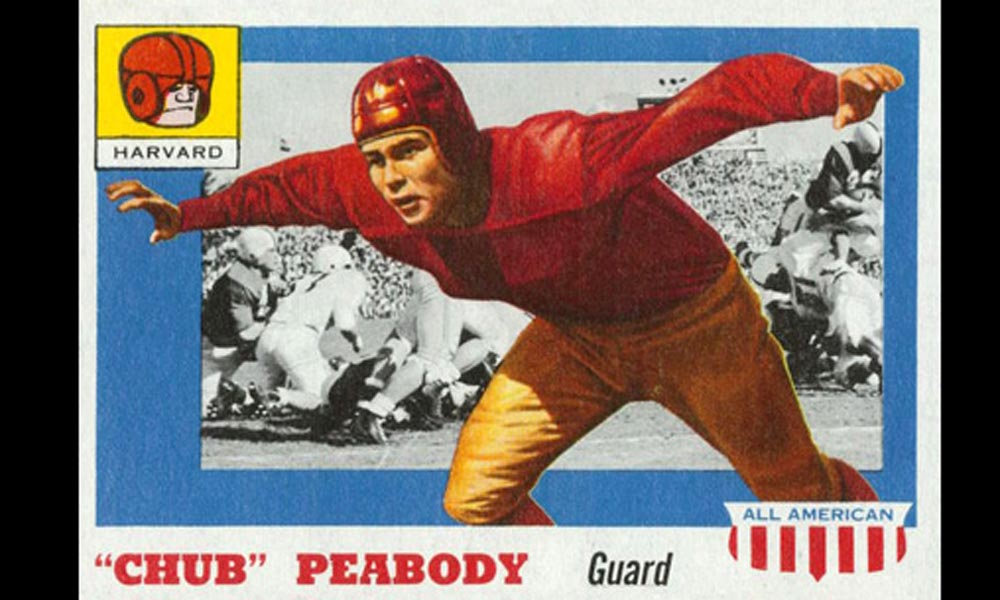

Athleticism ran in the Peabody family. His grandson Endicott “Chub” Peabody graduated from Harvard in 1942. He was an All-American defensive lineman for Harvard and was later inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame. During World War II he was a Navy lieutenant and received the Silver Star, for gallantry during action in the Pacific aboard the USS Tirante. In 1962 he was elected governor of Massachusetts.