The red dust of the Arabian Desert might have settled and cleared after Hidalgo’s epic cinematic ride in the well-done 2004 movie, but it’s nothing compared to the dust kicked up by critics of Frank T. Hopkins’ self-proclaimed heroics.

It would appear that his claims to have successfully ridden over 500 races, to have belonged to Buffalo Bill Cody’s Congress of Rough Riders, to have been half-Sioux, to have, in fact, played even the slightest role in the settlement of the West may be just so much … well, horse-pucky. It’s almost enough to destroy our faith in heroes. Almost.

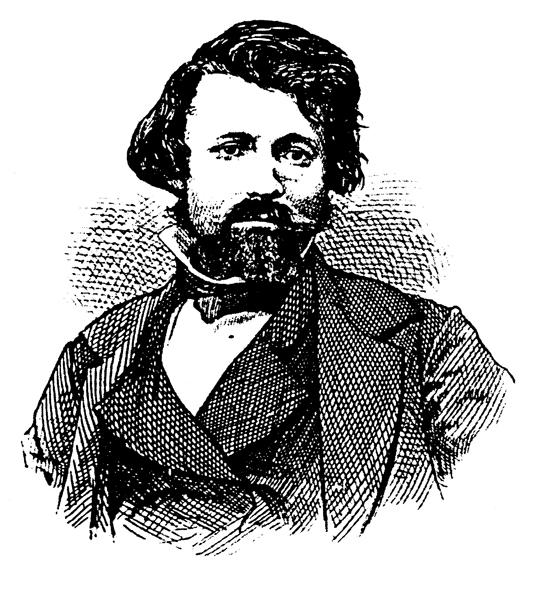

It seems there really was a man—modest, soft-spoken—whose exploits on horseback are the stuff of legend, but are absolutely, unquestionably true. He raced against the clock, and when he rode, he was known from Missouri to California. His full name was Francois Xavier Aubry—Francis, or F.X., to the Americans—but standing only 5’2″ tall and weighing a mere 100 pounds, he was known as “Little Aubry.” And he was the greatest speed and distance rider in the history of the West.

No Man Could Match His Fame

A young French Canadian, Aubry saw a fortune to be made in the Santa Fe trade. He left Quebec and the family farm at 18, and in 1843 made his way to St. Louis. After working as a clerk for three years, he bought a load of goods on credit and joined a party of traders, paying them to haul his freight. Leaving Missouri in early May, they arrived in Santa Fe nearly two months later. The war with Mexico had started while they were en route, and the old town was in the hands of Americans who craved goods from the “U. States.” Aubry and his fellow traders provided a wide variety of items; one trader, two years later, printed a list of his wares that filled columns in the Santa Fe Republican: knives, dirks, pistols, guns, rifles; Madeira wine, muslins and mackerel; hammers, hatchets, and silk hose; candles, cravats, and cotton thread; and, of course, all manner of liquors. Aubry proved to be a shrewd businessman; after selling his goods, he returned to St. Louis, where he paid off his debt and kept a hefty profit besides.

The following year, not satisfied with paying others to carry his inventory, young Aubry raised thousands of dollars, bought wagons and supplies, and formed his own caravan to Santa Fe. He offered to carry the mail from Missouri to New Mexico at a time when there was no organized system for mail delivery to the West. Aubry was filling a deep need; homesick Americans in New Mexico were starved for news from the states and for word from home. Still, the trip took over two months, with one man killed and scalped. By the time Aubry arrived, welcome though he was, the news was old.

Restless after selling his goods, Aubry immediately left Santa Fe for Independence, with dozens of wagons and a company of Missouri volunteers. Again, he carried the mail. When they were over halfway to Missouri, Aubry broke from the train and raced ahead alone, arriving in Independence on August 31, having traveled 300 miles in only four days.

Within weeks, Little Aubry loaded another caravan—out of season, since the Santa Fe trains had always stopped by September—and started for New Mexico. Again, he left the train at a gallop, taking the mail and three men along, and raced toward Santa Fe. This time, they were chased by Indians, but they made it in safely, ahead of the trade wagons. His daring rides through dangerous country were news, and Aubry was written up in the Daily Missouri Republican and the Santa Fe Republican. Everyone waited to see what the brave rider would do next.

Aubry was a restless man by nature, and he’d been bitten by the speed bug. Late in December 1847, he once again collected the mail and then stated his intention to ride muleback to Independence in 18 days, in an attempt to break the existing 24 1/2-day speed record. He took five men with him, but he and his crew soon ran into serious trouble. Mexican bandits stole 10 of their mules, and Aubry’s party rode three more to death. They were beset by Indians, and they were stuck for 10 hours in a blizzard. All five of his companions, overcome by exhaustion, quit, leaving Aubry to finish the trek alone. Despite setbacks, he made the 800-mile ride in 14 days.

The Missouri Daily Republican trumpeted Aubry’s success, stating, “Such a rate of travel is unprecedented in Prairie life, and speak[s] much in favor of Mr. A’s indisputable courage and perseverance.” The feat amounted to considerably more than just riding fast over wild country, the article went on; in the previous year alone, 47 men had been killed on the Santa Fe Trail, and 330 wagons and 6,500 head of stock either destroyed or stolen.

Only four years had passed since Aubry arrived in St. Louis from Quebec, and he was already a legend across the frontier. By now, Aubry’s pattern was fixed: Deliver goods and mail by caravan to Santa Fe, and race back to Independence. After escorting another of his trains to New Mexico, he prepared to ride for Missouri, seeking a 10-day record. This time, he rode alone. Along the way, he was taken by Comanches, who stole his food and the mail. Aubry escaped and raced on, riding three horses and two mules to death. Finally afoot, he walked 40 miles to Fort Mann, where he obtained a fresh mount and rode into Independence—his time, an incredible eight days, 10 hours!

Setting an Unbreakable Record

Every time Aubry set a record that couldn’t be broken, he broke it. And this was to be no exception. According to legend, he took a bet of $1,000—a vast sum, worth around $50,000 in today’s currency—that he could make the 800-mile ride to Independence in six days.

Aubry set about making his preparations as never before. Instead of relying on a single string of horses, he arranged to have hostlers stationed with mustangs at strategic points along the trail. In the dim light of early morning on September 12, 1848, Aubry bade goodbye to a handful of well-wishers in the Plaza, vaulted into the saddle and galloped out of Santa Fe. He first changed mounts in Las Vegas, New Mexico, and rode through the night into the second day. He found remounts at San Miguel and at Rio Gallina, and he galloped on, sometimes with only the horse beneath him, other times riding his mustang and driving one or two in front, “California style.” He tied himself on, ate as he rode and caught occasional brief naps in the saddle.

The relay stations were about 100 miles apart, and at one stop, he reined in long enough to bolt a cup of hot coffee and saddle his favorite horse, a Spanish mustang—he called her his “yellow mare”—named Dolly. He left camp at a gallop, pushing Dolly hard through a cold Autumn rain, but she bore up well.

As he sped past a westbound wagon train, he was observed by frontiersman, bullwhacker and entrepreneur Alexander Majors, who later wrote, “I met [Aubry] when he was making his famous ride, at a point on the Santa Fe Road called Rabbit Ear. He passed my train at a full gallop without asking a single question as to the danger of Indians ahead of him.”

Finally, Aubry rode into the camp where fresh mounts were to be waiting. He found the hostler recently killed and scalped, and the horses gone. Dolly had covered 100 miles, and now she would have to cover 100 more. This she did, in a record 26 hours, averaging around eight miles per hour. Aubry finally found a remount with a westering wagon train; he left his amazing yellow mare in the care of the wagon master, to be returned to Santa Fe.

Aubry rode on, through 24 hours of pouring rain and thick mud, crossing swollen streams, killing six horses and riding six more down. At one point, he found himself afoot, and, hiding his saddle, he walked over 20 miles to his next mount.

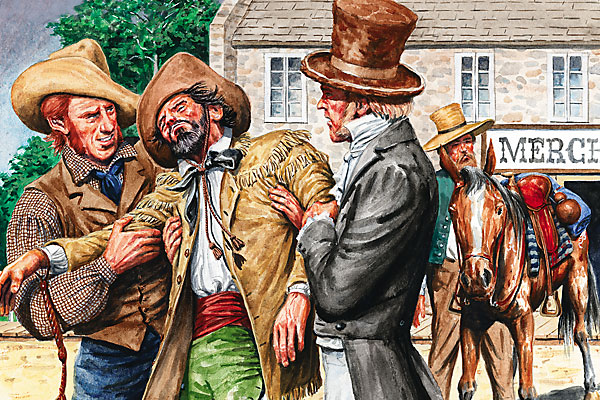

On the night of September 17, 1848, Little Aubry—nearly motionless aboard a played-out horse—stopped in front of Independence’s Merchants Hotel. With cries of, “Aubry’s here!” men dashed out to stare, to whisper their astonishment and to help him out of his saddle. When they cut the ropes holding him on, they found the saddle covered in blood.

Helped into the hotel, Aubry croaked an order for ham, eggs and coffee, and when he had finished eating, he finally slept. The black-haired little Frenchman with the trim goatee had ridden the 800 miles from Santa Fe to Independence in five days, 15 hours. He had won his bet, and he had set a record that would never be broken.

When he was awake and coherent, Aubry wrote a brief synopsis of his ride. It ends, simply, “made 200 miles on my yellow mare in 26 hours.”

An Unlikely Death

A few years later, feeling that the Santa Fe Trail had become too civilized, Aubry turned his attention farther west. In 1852, he mounted Dolly and led 10 wagonloads of goods, along with 3,500 sheep and 100 mules, to the California goldfields. The following year, while driving 14,000 sheep along the California route, he and his herders were attacked by Indians. Aubry’s August 3 entry in his journal reads, “Indians shooting arrows around us all day wounded some of our mules and my famous mare, Dolly, who so often rescued me from danger by her speed and capacity of endurance.” Aubry also writes that he himself had received eight wounds, “five of which cause me much suffering.”

With most of their food gone, the party of men was reduced to eating their horses. Dolly had succumbed to her wounds, and on August 16, Aubry wrote, “I have the misfortune to know that the flesh we are eating is that of my inestimable mare Dolly who so often saved me from death at the hands of Indians.”

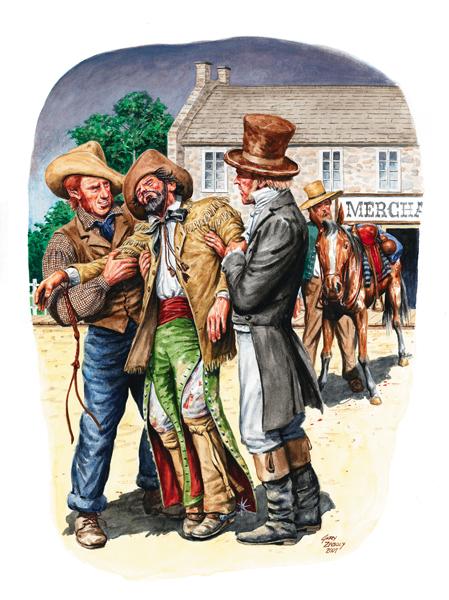

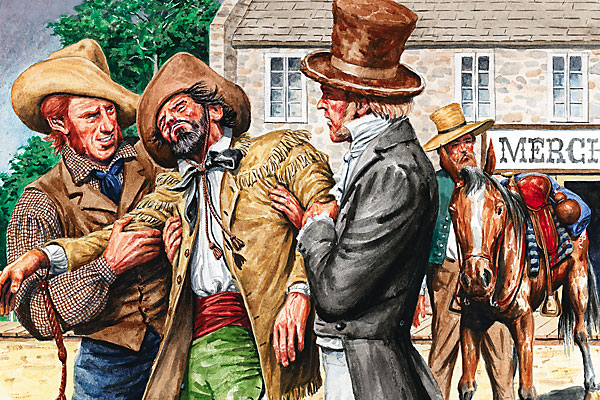

Little Aubry didn’t long survive his yellow mare. The following year, he rode to California in search of a central transcontinental railroad route from St. Louis to the West Coast. Upon returning to Santa Fe, he stopped for a drink at the Mercure Brothers’ store on the Plaza. There he encountered Richard H. Weightman, former editor of a defunct local newspaper. Weightman was a sometime military man, blustery and quick to anger. As a youth, he had been expelled from the U.S. Military Academy for slashing a classmate’s face with a Bowie knife. As he and Aubry sat, drinking their wine, an argument ensued. In some versions, it was over the best route for the railroad; in others, a slight to Aubry published in Weightman’s newspaper. Almost at once, Weightman drove his knife into Aubry’s stomach, killing him almost instantly. He was 29 years old.

Weightman was arrested and tried for murder. So popular was Aubry with the citizens of Santa Fe that a guard had to be placed outside his killer’s cell for his protection. Ultimately, Weightman was acquitted when his attorney argued that Aubry’s death came under the unwritten law of the duel; the defendant had claimed that Aubry was drawing a pistol when stabbed.

Shortly before the fatal encounter, a new steamboat was built and christened the F.X. Aubry. Between the smokestacks was bolted the wooden figure of a small man astride a yellow mustang. The boat would be the fastest on the Missouri.

Alexander Majors, who had witnessed that brief moment in Aubry’s legendary ride, later wrote, “This ride, in my opinion … was the most remarkable ever made by any man. The entire distance was made without stopping to rest…. At the time he made this ride, in much of the territory he passed through he was liable to meet hostile Indians, so that his adventure was daring in more ways than one. In the first place, the man who attempted to ride 800 miles in the time he did took his life in his hands. There is perhaps not one man in a million who could have lived to finish such a journey.”

Just six years later, Majors, with his partners, William H. Russell and William B. Waddell, launched an enterprise for the fast cross-country delivery of the mail. They officially called it the Central Overland and Pike’s Peak Express Company, but no one could handle such a mouthful, and the company was simply called the Pony Express. The ad the partners placed seeking carriers read, in part, “WANTED: Young, skinny, wiry fellows…. Must be expert riders. Willing to risk death daily.”

As Alexander Majors would have been the first to acknowledge, they were describing F.X. Aubry. In the words of one historian, “Americans love a race and they love a winner, and they loved that man on the horse.”

Ron Soodalter’s Hanging Captain Gordon: The Life and Trial of an American Slave Trader is published by Atria Books.

Photo Gallery

– Illustrated by Gary Zaboly –

– True West Archives –

– All photos by Henry Hamlin –

— Frederic Sackrider Remington, “Spanish Horse of Northern Mexico,” The Century magazine, January 1889 –