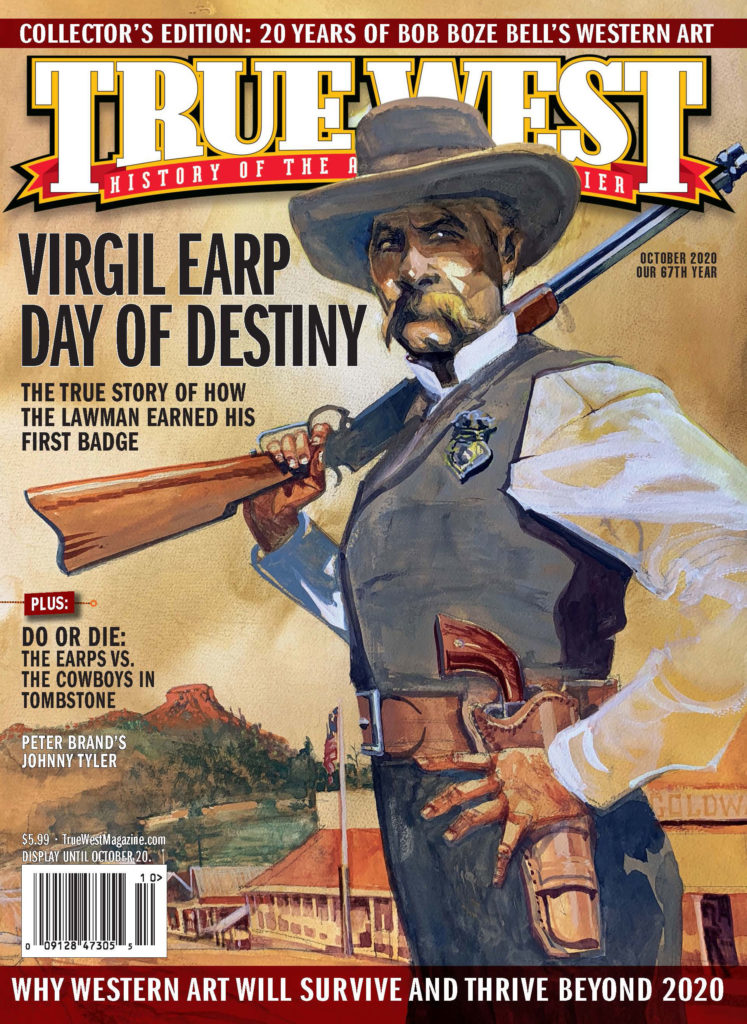

So great is the shadow cast by Tombstone’s legendary 1881 shootout at the OK Corral, it is not widely known that Virgil Earp’s law-enforcement career began in Prescott. Its launching point was a prominent saloon along Whiskey Row.

In 1877, the Jackson & Tompkins’ Saloon at 134 South Montezuma Street near the center of Whiskey Row was one of the top four saloons in Prescott. On October 17 of that year, Col. William McCall, a Pennsyl-vanian who had been brevetted general during the Civil War, was enjoying a game of billiards therein. That is when two men, George Wilson (calling himself “Mr. Vaughn”) and Robert Tullos (aka John Tallos), walked in and made a beeline for McCall. One jabbed a pistol in his back while the other whispered threats in the colonel’s ear, something like “Keep your mouth shut or else!”

Why convey such a warning? A few months prior, McCall had been living near the Texas/Oklahoma border. While there, he learned Wilson had murdered Robert Broddus (sometimes spelled Broaddus), deputy sheriff of Montague County, Texas. Very possibly, McCall played a part in chasing Wilson, who proved elusive. The murderer fled to Colorado before journeying to Prescott. So to Wilson’s surprise, and knowing McCall was aware of his crime, he spotted McCall and was concerned the colonel might cause him trouble.

The killing occurred when Deputy Sheriff Broddus was escorting Wilson from Collin County to Montague County to stand trial for an undisclosed misdemeanor. With Broddus were two guards, Bud McGary and Tom Lemans. The three lawmen and the prisoner were camping one spring morning in Denton County along Bolivar Creek. The guards were making breakfast. Suddenly, Wilson grabbed McGary’s gun, pulled the trigger and shot Broddus to death. He then snatched Broddus’s horse.

Apparently, Wilson had at least a smidgen of scruples. Before escaping, still holding his gun on them, Wilson offered McGary and Lemans $20 for a saddle. The guards refused but, bafflingly, sold a pistol to the outlaw for $10, and then gave him a blanket so that he would not have to ride bareback on Broddus’s horse.

On June 2, 1877, Texas governor Richard Hubbard, offered $500 for the capture or death of Wilson. He would up the ante in November, but by them, it was of no consequence.

Somehow Colonel McCall escaped Jackson & Tompkins’ and dashed straight into the office of Justice of Peace C. F. Cate and reported the presence of the outlaws. Cate issued an arrest warrant for “Mr. Vaughn” and “John Doe”; Tullos was a stranger to McCall, and perhaps McCall really believed Wilson’s last name was Vaughn. Cate gave the warrant to Constable Frank Murray who immediately strode over to Jackson & Tompkins’, followed by McCall.

Prior to their arrival, the two no-goods—clearly soused—had stepped outside, and one took a potshot at a woman’s dog as they strolled along Prescott’s plaza. When Murray arrived, the scoundrels believed they were being held accountable for discharging the gun at the animal. Told otherwise, both drew their pistols, quickly mounted up and galloped their horses south down Montezuma while shooting to the left and right.

Murray gathered an all-star posse. But it took a bit of time, which gave the desperadoes a head-start advantage.

Somewhere in Prescott, three men were engaged in friendly conversation, far enough away to be oblivious to what just transpired. Two were high-ranking lawmen: Yavapai County Sheriff Ed Bowers and US Marshal Wiley Standefer. It is likely that these lawmen would have hurried to the sound of gunfire had they been close enough to hear it.

Bowers, along with Murray, would take up the chase on horseback. Standifer and McCall hopped aboard the marshal’s horse-drawn carriage.

The third man was Virgil Earp, new to Prescott and so little-known that the Miner repeatedly reported his name as “Mr. Earb.” However, he was toting his Winchester rifle. Given the situation, that might come in handy.

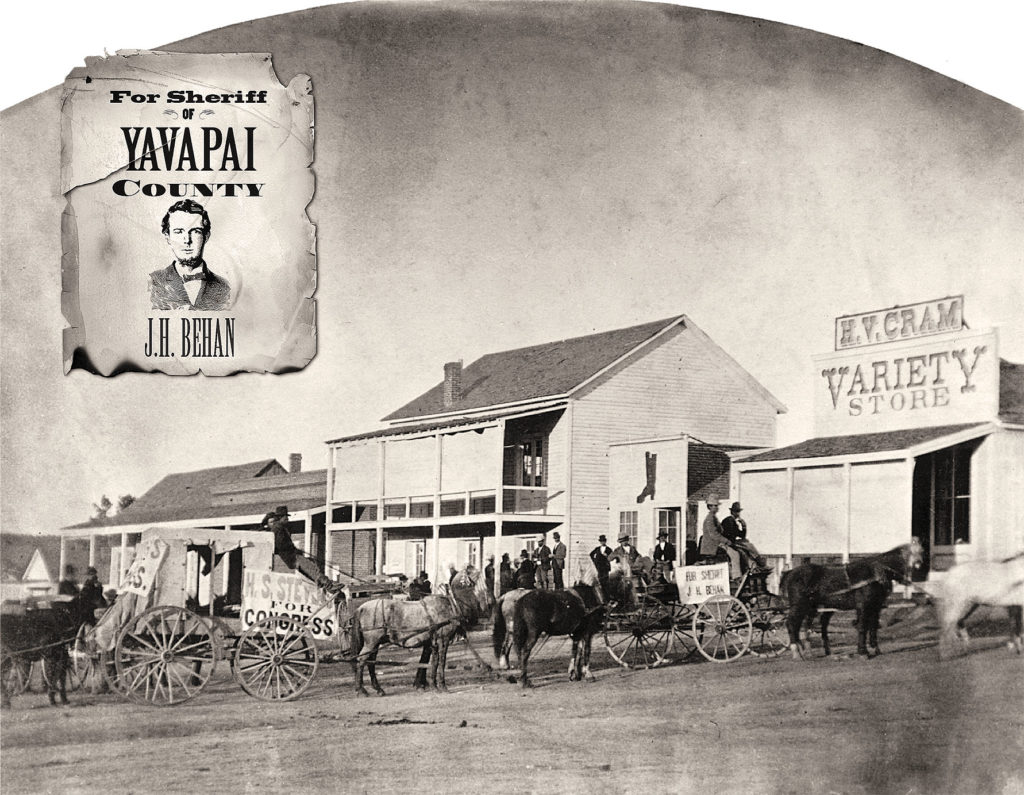

It’s election time in the new capital of Arizona. Hyram S. Stevens is running for the legislature and John H. Behan is running for sheriff of Yavapai County. Both win. Behan has been active in politics since his arrival in Arizona, having served as representative of Mojave and Yavapai counties. However, Behan trips when he runs for recorder in August of 1880. He is bitter about the defeat, feeling he wasn’t adequately backed by his Democrat friends. He will receive a bone in about six months.

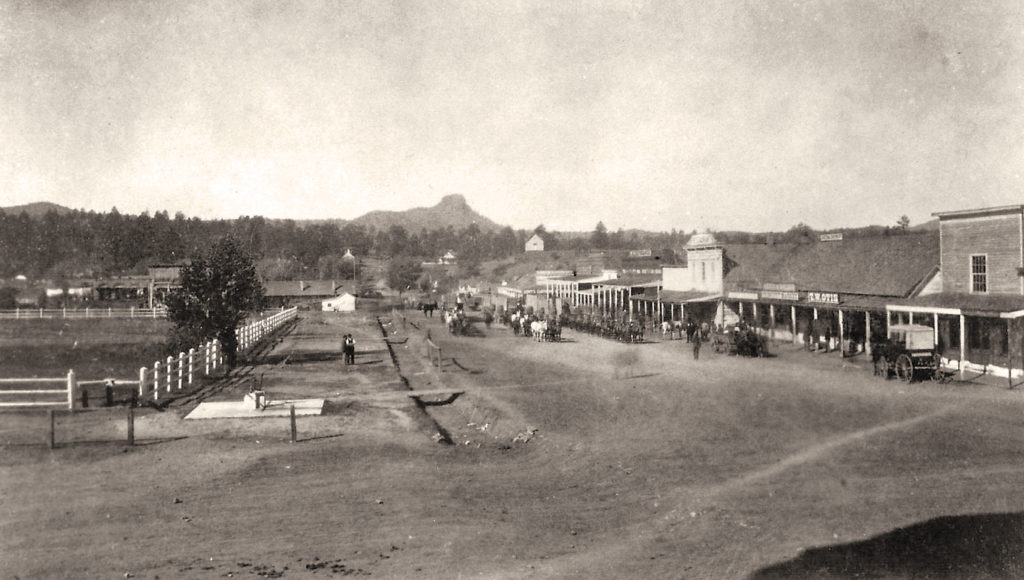

Meanwhile, Virgil Earp has been driving a stage to the surrounding mining camps including Tiptop (where Johnny Behan lives), Agua Fria, Gillett, Black Canyon, Humbug, Big Bug, Cottonwoods, Bumblebee and the little village of Phoenix.

– Photo courtesy of Sharlot Hall Museum –

A freight wagon like the ones Virgil and Wyatt manhandled across the Mojave Desert, approaches Prescott, Arizona Territory in the 1890s.

– Photo courtesy of Dorothy McLaughlin –

Most Old West historians—including his biographer Donald Chaput—believe that Virgil had never been an official lawman up to this point. Virgil claimed that he served in some capacity as a lawman in Dodge City, Kansas, with brother, Wyatt. Yet, there is no documentation verifying this.

Virgil, however, must have made an impression upon the three lawmen, and the Civil war veteran—he, too, had fought for the Union Army—and he was promptly deputized. But Earp had no horse at the time, and there was room for only two on the carriage. He would have to keep up on foot!

Wilson and Tullos were expected to be far down the trail by now. How long could Virgil last? Fortunately for him, the chase would not be a long, heroic, Western movie-like affair, but more like a scene from Mel Brooks’s Blazing Saddles.

The outlaws, instead of distancing themselves from Prescott, stopped about a half mile (perhaps less) southwest of the Row, probably on the corner of Carleton and Granite streets by Prescott’s main waterway, Granite Creek. Both dismounted with pistols pulled. They lit up their cigarettes and waited.

– Courtesy Bill Koch Collection –

Standefer and McCall, leading the posse and moving fast, rode right by the fugitives. Lucky break for the outlaws? Yes, until one of them shouted, “Don’t run over us, you son of a bitch!”

Imagine what the other outlaw thought at this outburst.

The two posse members halted, jumped off the carriage and turned their pistols on the bad men. Murray and Bowers, riding down from the north, dismounted and did the same. Earp quickly caught up, positioned himself between the four other lawmen and shouldered his Winchester.

Hearing the demand to surrender, Wilson vociferously entreated God, “O’ Lord have mercy on me, a poor drunken, worthless damned son of a bitch.”

The criminals opened fire.

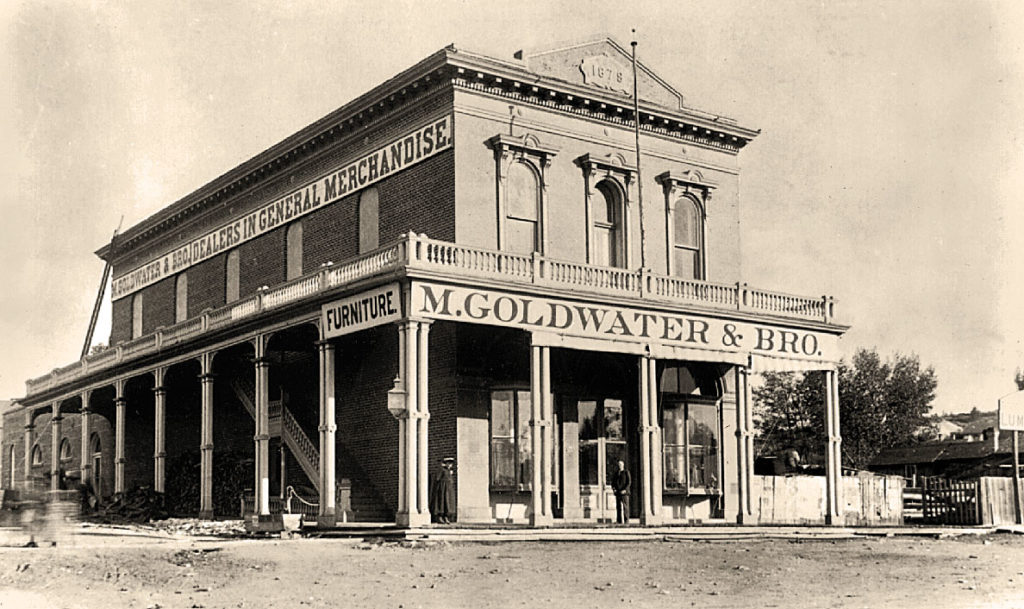

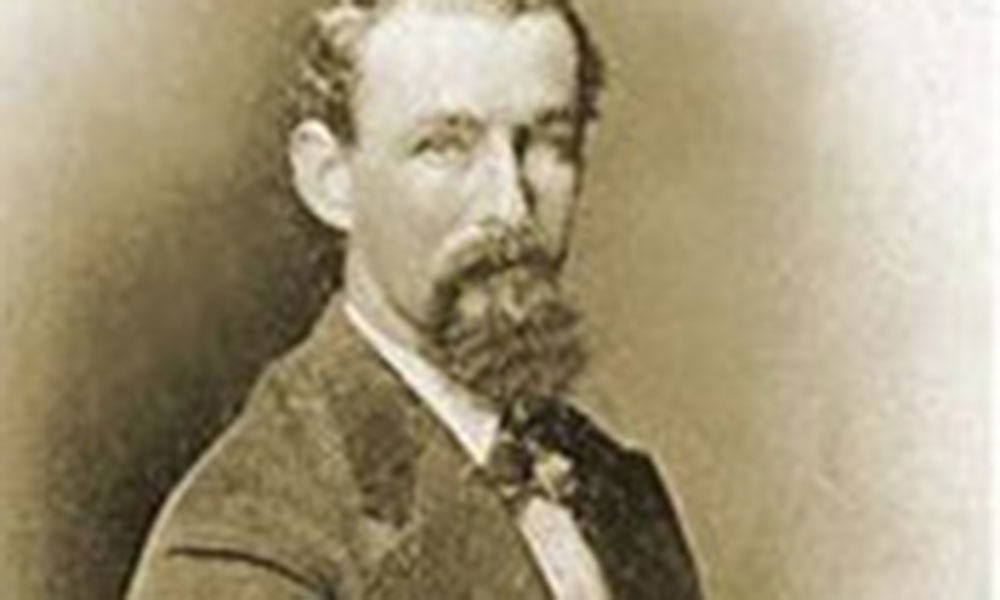

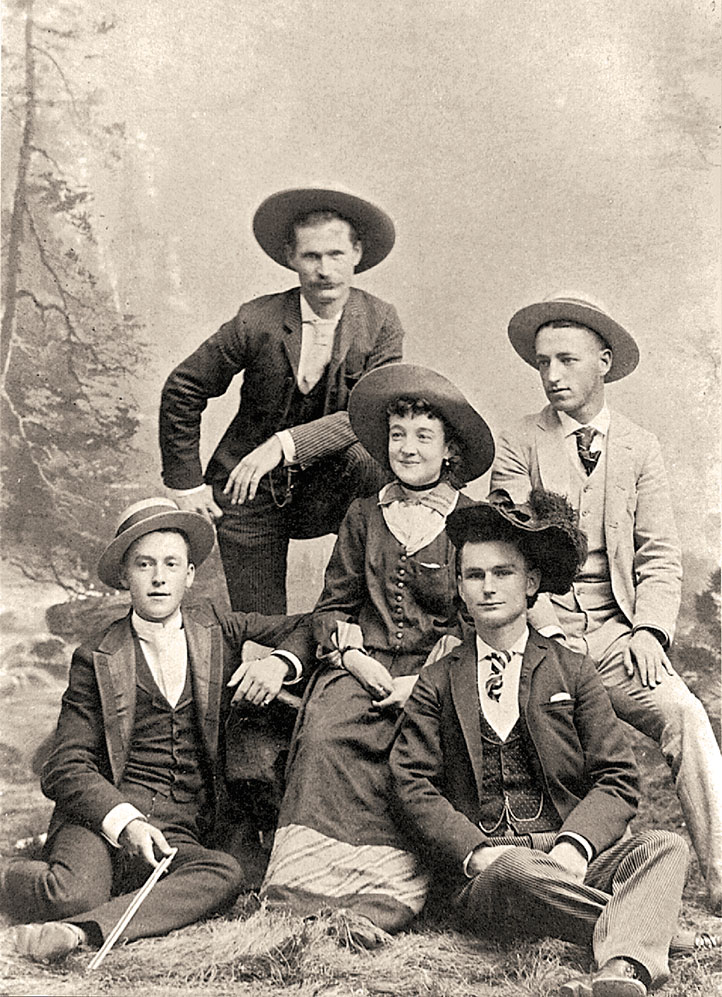

“Big” Mike Goldwater (standing) gets ready to go on a picnic with friends in 1880. It was no picnic when customers left without paying for goods and that’s what Virgil and Allie allegedly did to Mike. The Goldwater store (below) was a fixture in Prescott and later became a successful chain.

– photos courtesy of Sharlot Hall Museum –

Bullets and buckshot came from three directions. Wilson fell immediately when a bullet penetrated his skull. Tullos died instantly after being shot eight times. Most, if not all, of those wounds came from Virgil’s Winchester.

To the astonishment of many, George Wilson hung on for two days with a bullet lodged in his head. The Miner boys turned theological those two days, wondering if the prayer Wilson bellowed before being shot had any effect because of the sincerity behind it—even with its profanity. “It was the language with which he was familiar. The question is, are not such earnest prayers as likely to be answered as those hypocritically expressed in more elegant phrase?” the Miner speculated.

All for naught. Wilson died with a bullet still in his brain.

An interesting side note to this story is that Virgil’s younger brother Wyatt had dealt with Wilson in Wichita, Kansas, in 1875 when he was a policeman there. Apparently, Wilson had “forgotten” to pay for a wagon he had acquired. Wyatt came to collect, and did so after a bit of firm prompting.

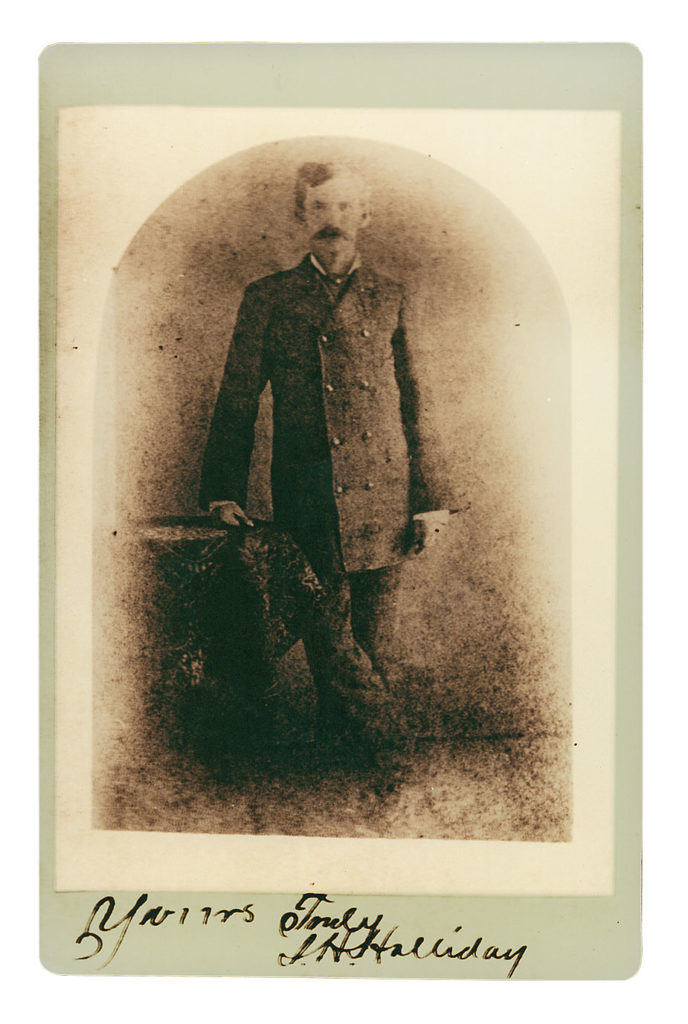

It is perhaps in this very boardinghouse, above, that Doc Holliday roomed with the Arizona Territory’s secretary of state and the future acting governor John J. Gosper.

This nugget of Arizona history has dismayed many Holliday researchers, who are deeply disappointed that Doc would have sunk so low as to have roomed with a politician.

– Sharlot Hall Museum Library/Archives, Prescott, Arizona –

Small world. Small Old West world.

It was later learned that Wilson was more evil than first thought. He was also wanted for the murders of the sheriff and deputy sheriff of Las Animas County, Colorado.

This episode proved to Prescott-onians that Virgil was a man who could be counted on and a crack shot with a rifle. He was soon appointed Prescott’s nightwatchman, and elected constable in 1878. Ironically, he defeated the very man, Frank Murray, who made him a member of the October 17 posse.

On November 1, 1879, after a series of correspondences between the brothers, Wyatt and his wife, Mattie, and older brother, James and his wife, Bessie, and two children, arrived in Prescott with Doc Holliday and Kate Elder in tow. Doc and Kate had joined them in Las Vegas, New Mexico Territory. In late December of 1879, Virgil and Wyatt arrived in Tombstone, the territory’s latest boomtown. Morgan most likely arrived sometime in the spring of 1880.

Doc Holliday, ever the sporting man, stayed in Prescott with Kate to gamble on Whiskey Row until early 1880, before she went to Globe and he went back to Las Vegas. In May, Doc returned to Prescott, where he roomed with Territorial Secretary John Gosper and a temperate miner Richard E. Elliot on Whiskey Row until he left for Tucson in July. He would rejoin the Earps in Tombstone on September 14, 1880. A little more than a year later, on October 26, 1881, in a 30-second gunfight, the three Earp brothers and Doc Holliday shot their way into eternal fame.

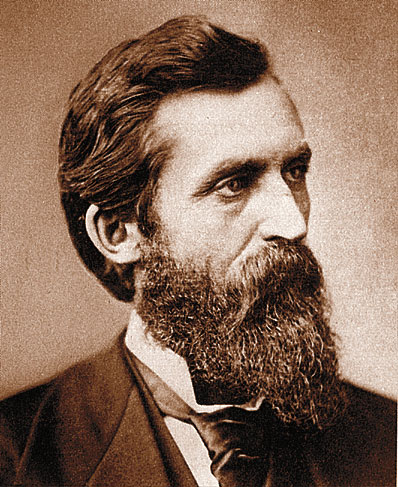

As head of the marshals in Arizona, Crawley gives Virgil his commission before Earp goes to Tombstone. A staunch supporter of the Earps, he will be sued by the federal government for the $3,000 he gives Wyatt to pursue outlaws.

June 2, 1880

When the Earps leave Prescott in November of 1879, Doc and Kate stay in the mile-high city. Doc Holliday shows up on the Prescott, A.T. census. He is rooming on Montezuma Street with two men, Richard E. Elliott, 45 (a good friend of Virgil Earp), and John J. Gosper, 39, the future acting governor of Arizona Territory. (Gosper is the secretary of state, but the official governor, John C. Frémont, is rarely in the territory and the duties fall to Doc’s roommate.) It’s unclear where Kate is during this time.

Stuart Lake will later claim in his book Frontier Marshal that Doc hit a winning streak playing faro on Whiskey Row and ran up a $10,000 poke, but Earp historian John Gilcrease thinks the figure is wildly inflated, stating, “Doc Holliday never saw that much money in his life.” Surprisingly, for those who imagine Doc and Wyatt joined at the hip, Holliday gets to Tombstone about ten months after the Earps arrive.

Bradley G. Courtney holds an M.A. in history from California State University-Dominguez Hills. He is the author of Prescott’s Original Whiskey Row and The Whiskey Row Fire of 1900.