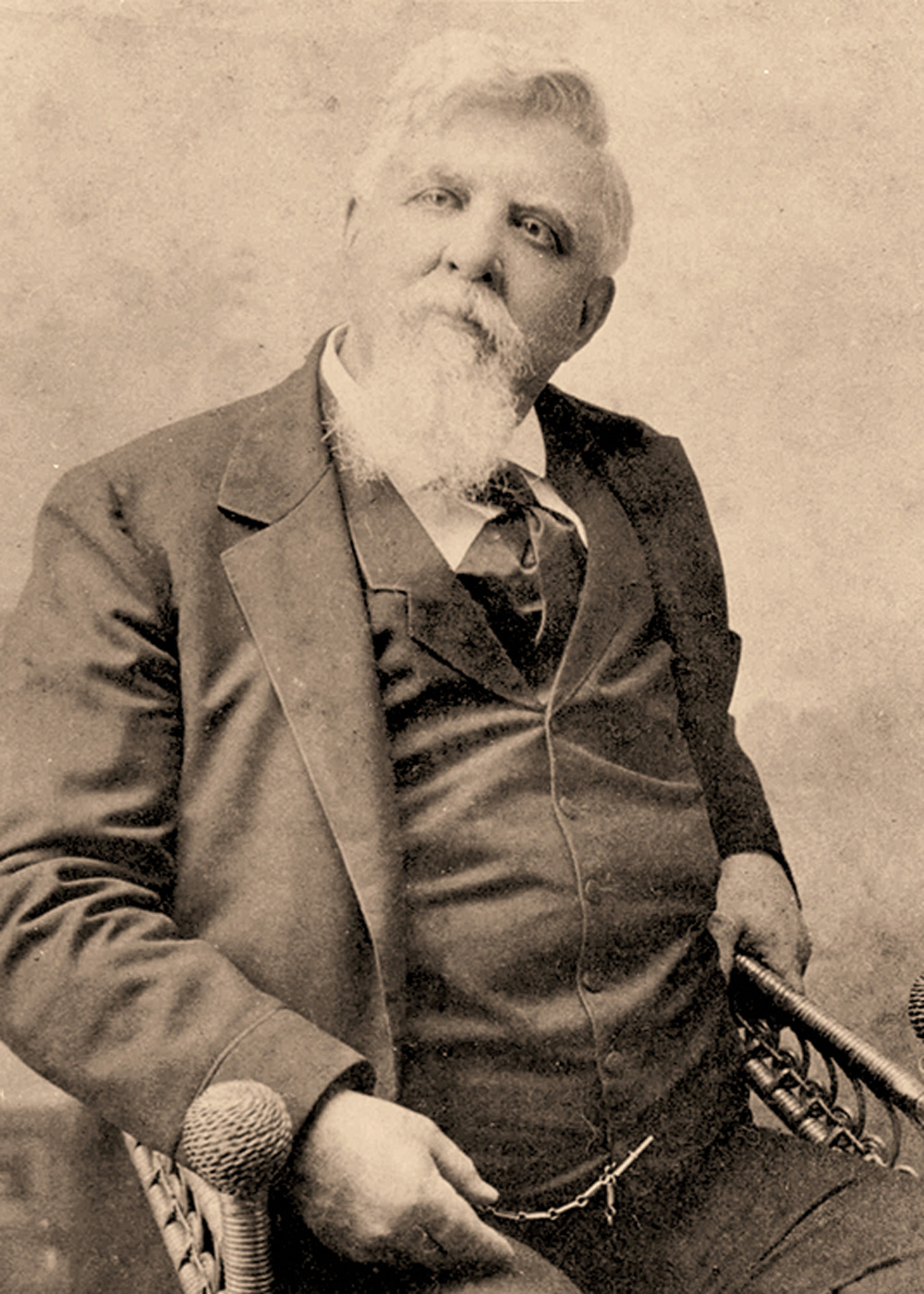

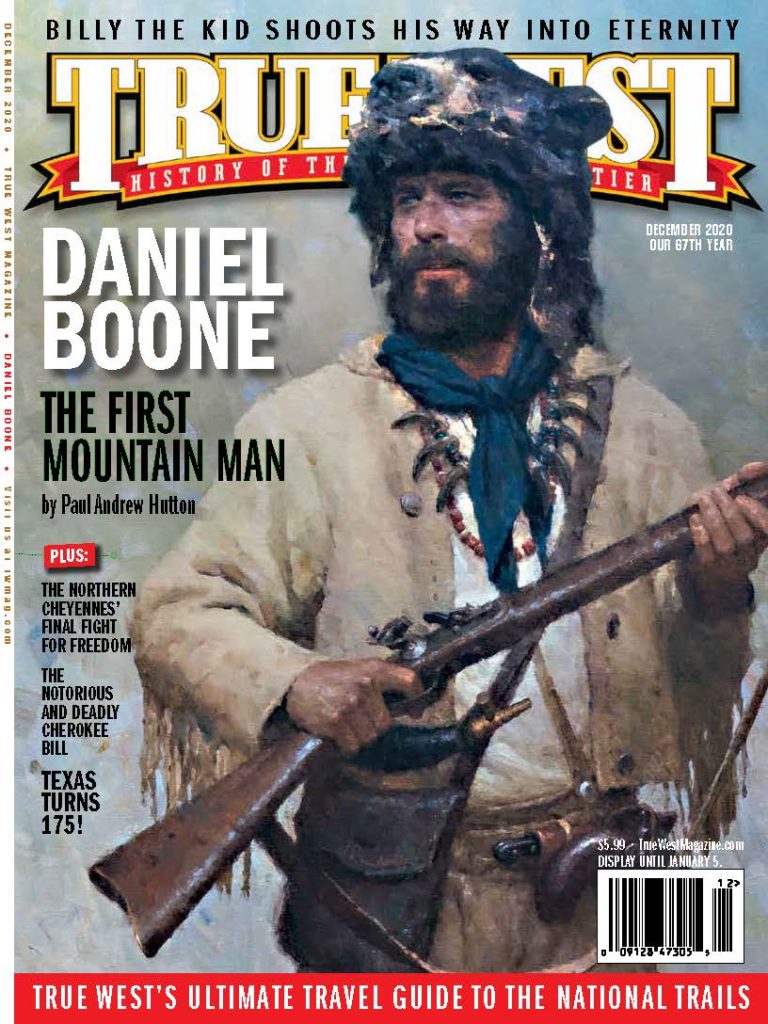

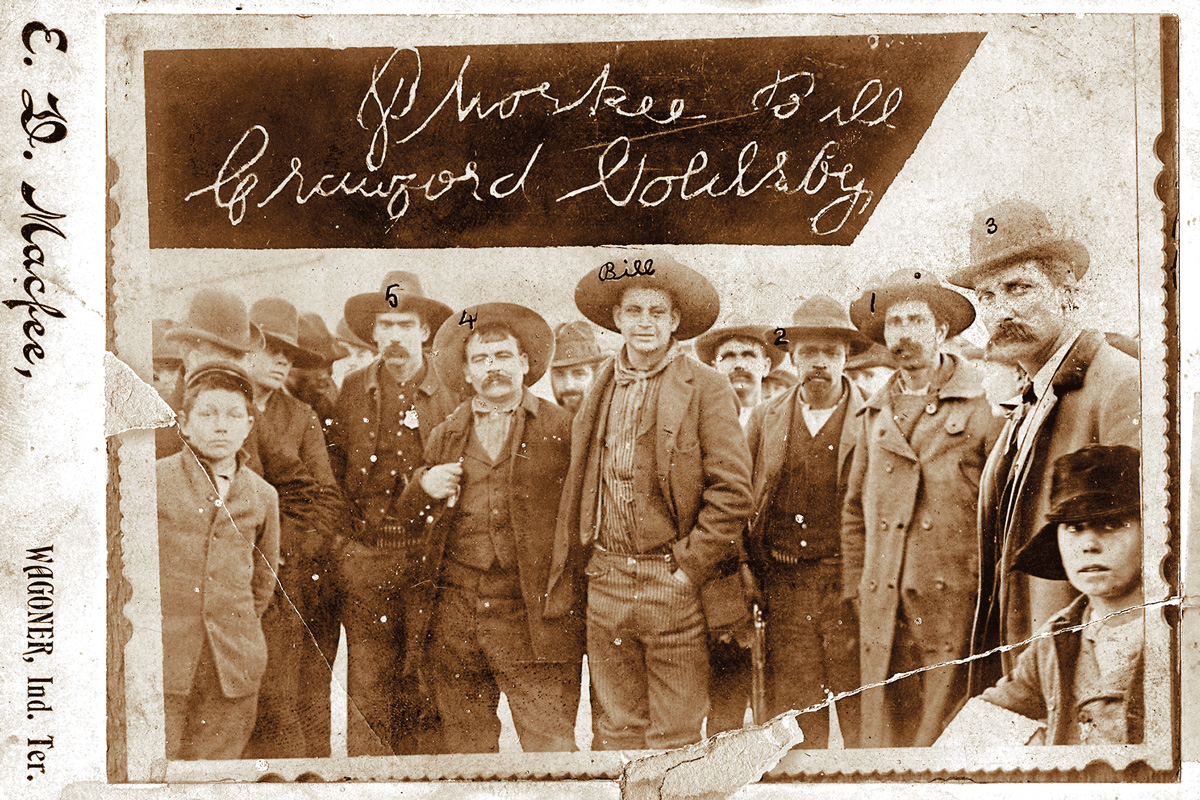

– Photo of Cherokee Bill Courtesy True West Archives –

Cherokee Bill can be compared to John Dillinger and Pretty Boy Floyd of the 1930s. Like these men, he garnered national press for his exploits; the well-known New York Times had a running commentary on his actions and deeds in the Indian Territory. Cherokee Bill was every bit as colorful and outrageous as any criminal on the Western frontier, perhaps even more so. There were a few things about him that made him truly unique for a famous desperado of the purple sage. First and foremost, he was an African American living in the Indian Territory. He was also a Native American, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation as an Indian Freedman from his mother’s lineage. Compare Cherokee Bill to Billy the Kid of New Mexico Territory fame. Although both outlaws received national media attention for their crimes while they were living, Billy the Kid was remembered and immortalized in books and films in the 20th century, but this did not occur for Cherokee Bill.

The boldest and most brazen robbery by Cherokee Bill and the Cook gang occurred on Monday morning, July 30, 1894, when the gang robbed the Lincoln County Bank in Chandler, Oklahoma Territory. Chandler was the county seat of Lincoln County; a few years later, the famous Dodge City, Kansas, lawman Bill Tilghman would become sheriff of Lincoln County.

At about ten o’clock on that July morning, five heavily armed cowboys rode into town from the northeast, coming down Manvel Avenue to 7th Street, where they turned and went to the alley. They rode behind Fletcher’s Hardware Store and stopped at the rear of the Lincoln County Bank, where they dismounted….

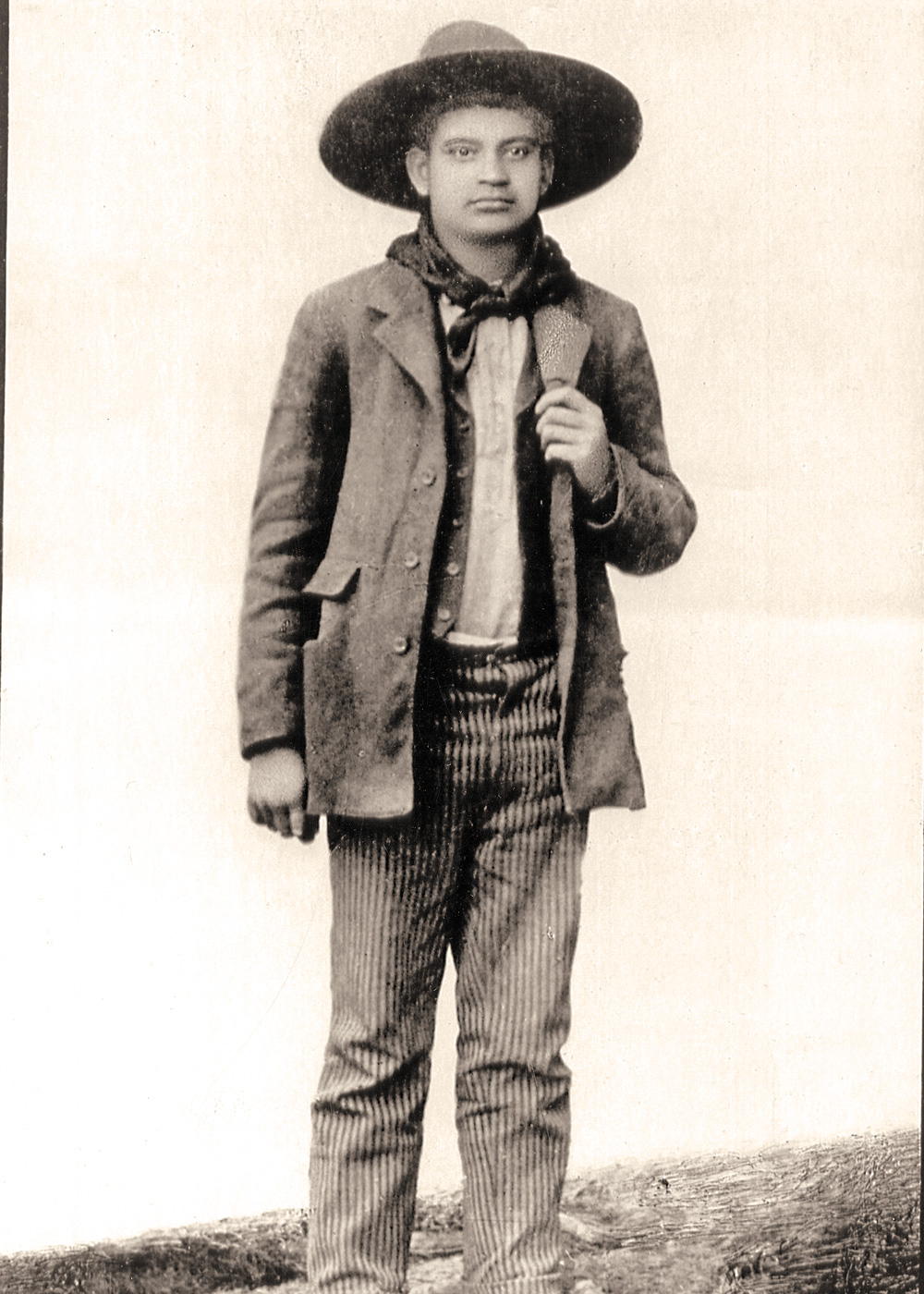

– Courtesy Author’s Collection –

The Guthrie Daily Leader earlier on August 1, 1894, carried a front-page story that said:

DASTARDLY DEED OF DEMONS.

THE LINCOLN COUNTY BANK AT CHANDLER LOOTED.

A CITIZEN RUTHLESSLY SLAIN.

Sheriff Parker and Posse Give Chase. A Terrific Battle and as Outlaw Brought Town – Now Safe Behind the Bars. A Mere Boy is He but the Others are Old Timers – Latest Job of the Notorious Cook Gang.

Special to the Leader.

Chandler, Ok., July 31. – The quiet and serenity of this little city was rudely disturbed yesterday morning by a bold bank robbery. About 9 o’clock, five horsemen dressed as typical cowboys and heavily armed, rode into town from the north along the street east of the court house, and turning down the alley back of Fletcher’s hardware store, proceeded to the rear of the Lincoln County Bank where they dismounted.

One of the men held the horses while two entered the building from the rear and one from the front entrance simultaneously, while another remained on the guard on the outside.

Mr. Harvey Kee, president of the bank, was at the teller’s window, when one of the men stepped up and presenting a Winchester said, “Say, you d— s— of a b—, shell out your cash, and be d—d quick about it too.” At the same time, noticing O. B. Kee, the cashier, at the books, he ordered his pal to attend to him.

The third bandit then went to a room in back of bank building where F.B. Hoyt lay very sick, and compelled him to get up to open the safe. Hoyt came in at the point of a Winchester and made an effort to open the safe but was so nervous that he did not succeed, although being roundly cursed for his delay and having a Winchester snapped in his face once or twice.

About this time, shooting commenced on the outside which so excited the bandits on the inside that they grabbed up what money they could find on the top of the counter, (about $300) and skipped out. They could have got two thousand dollars by pulling out the tellers draw just below. As they were leaving, one of the fellows jerked off O. B. Kee’s watch and put it into his pocket.

On the opposite corner from the Lincoln County Bank, J. B. Mitchell has been conducting a barber shop. He was sitting out in front of his shop, and noticing the movements of the bandits called out “the Dalton gang in town,” and got up and started to go into his shop, when the fellow in front of the bank, called to him to “shut up and sit down.” He did not heed the admonition however, and started to go into his shop, when the bandit shot killing him instantly, the bullet entering on his right side, between the fourth and fifth ribs and piercing his body.

By this time there was a general fusillade between bandits and citizens, fully 100 shots being fired. As the robbers were mounting to ride off, N. W. Warren, a deputy U.S. marshal killed one of their horses, (since ascertained to be Bill Cook’s) but the owner got up behind one of the others and all rode off in the same direction from whence they came – the Creek country.

Sheriff Parker immediately organized a posse and started in pursuit. At the edge of town another one of their horses was killed. They overtook an old German in a cart, took his horse out of the cart and rode on. They also made old man Pollard dismount and appropriated his horse also. The sheriff and posse came up on them near Chuck-a-hoe on section 36, 15-4, and a hundred or more shots were fired. One of the bandits were shot and taken prisoner. The others scattered through the woods and were lost track of. The sheriff and posse feeling that they had achieved enough glory for one day returned home. The prisoner captured is a young boy of the typical cowboy order, aged about 21 years. He gives his name as Elmer Lucas. He is shot through the hips the ball going through his body, making a painful and ugly, but not seriously fatal wound. He gives the names of the band of outlaws: Bill Cook, Tom Cook, Jack Starr or Cherokee Bill (a Cherokee Indian) and the prisoner. He says they are known as the Cook gang and that he joined them at the…ranch in the Creek nation only last Monday.

J. B. Stewart , the liveryman says that he remembers that the horse that was killed, was put up at his stable last Friday. It is evident that they were posted, because they knew exactly how to get into the rear of the Lincoln county bank. One of the gang was seen in the rear of Hoffman, Charles & Conklin’s bank about an hour before the hold-up. A number remember the fellows loafing around last night, (Sunday) and this morning one of them purchased two or three bottles of whiskey at Reeve’s saloon.

Mr. Mitchell, the gentleman shot, was a quiet, unoffensive citizen aged fifty-three years. He leaves a wife and two daughters in straightened circumstances. The people are very much worked up over the affair and are in favor of meting out summary justice to all the gang should they be captured, but as they made directly for their haunts in the Creek country, and are now safely hiding in the canyons and caves of that section there is little hope of capturing them.

Cherokee Bill was one of the two outlaws out in front of the bank. When J.B. Mitchell started screaming about the bank being held up, Cherokee Bill called to him to shut up. When Mitchell tried to stand up from his chair, Cherokee Bill leveled his Winchester rifle and shot the barber at a distance of about 200 yards. Mitchell staggered a few feet and fell to the sidewalk near the corner of the barber shop. Mitchell died within minutes of being shot; he was 53 years old and left a wife and two young children.

When the outlaws came out of the bank, they fired their guns wildly in all directions. N.W. Warren, a county deputy sheriff, shot Bill Cook’s horse, and then Cook mounted up behind one of his gang. The gang was vigorously pursued by a posse put together by Sheriff Claude Parker, and a gunfight took place in some timber east of town. The August 3, 1894, Edmond Sun Democrat said the gun battle lasted for 15 minutes and over two hundred shots were exchanged. One of the gang, Elmer Lucas, was wounded and captured by the posse. The rest of the gang was able to escape into the hills. Lucas was taken back to Chandler, but due to anger over the death of Mitchell and calls for a lynching, he was transported to the federal jail at Guthrie, capital of the Oklahoma Territory. While he was in custody, Lucas named the other members of the gang. According to him they were Cherokee Bill, Bill Cook, Henry Munson, Jack Starr, Tulsa Jack and Lon Gordon. Under interrogation, Lucas also confessed to his involvement in the train robbery at Red Rock. Later, he was transferred to the federal jail at Fort Smith, Arkansas, where he was indicted for the train robbery and recovered from his wounds.

On July 31, Deputy U.S. Marshal Scott Huffvine, an Indian resident of Kellyville, got information that the Cook gang was going to meet on Polecat Creek in the Creek Nation. To be able to locate the gang, Huffvine got the most famous tracker in the Indian Territory to assist him. Tiger Jack, an Euchee Indian, a tribe closely aligned with the Creek Indians, had worked with quite a few deputy U.S. marshals, including Heck Thomas, in tracking down desperadoes. Tiger Jack picked up the trail of the gang, but they were too late, and the gang got away.

On August 9, Deputy U.S. Marshals Jesse Allen and Thompson Pickett—who were also Euchee Indians and members of the Creek Lighthorse Police—located the Cook gang with the aid of an Indian posse. Allen and Pickett had been hunting the Cook gang since the Red Fork robbery. The gang had been hiding out 14 miles west of Sapulpa, Creek Nation, in the home of Bill Province, the uncle of Henry Munson. It was 8 a.m. and the gang was outside the home washing up when the posse, about a dozen strong, came in with guns blazing. A desperate gun battle ensued resulting in about 40 shots fired between the parties. Henry Munson was killed; Lon Gordon was severely wounded; Curtis Dayson was captured; and one Indian policeman was wounded. Cherokee Bill, Bill Cook, Thurman Baldwin and Buck Snyder were able to escape a close call. Gordon later died from injuries—gunshots to the head and lungs—after being taken to Sapulpa.

Cherokee Bill was said to have had irresistible charm and a sweetheart in nearly every section of the territory. Cherokee Bill was often protected from harm by loyal friends and a violent reputation. Lawmen who pursued him, hearing of his deadly rifle accuracy and fast six-shooter action, kept a safe distance and many times avoided engaging him in battle. Because he was on good terms with Cherokees, Creeks and Seminoles, he moved easily through their villages and lands, something his pursuers could not do.

From the time Cherokee Bill joined the Cook brothers, he acted as though he was destined to die in two years and wanted to kill as many men as he could. Some of the fugitives who allied themselves to the Cook Gang that summer of 1894 were killed in desperate fights with deputy U.S. marshals; others were captured, convicted and given penitentiary sentences.

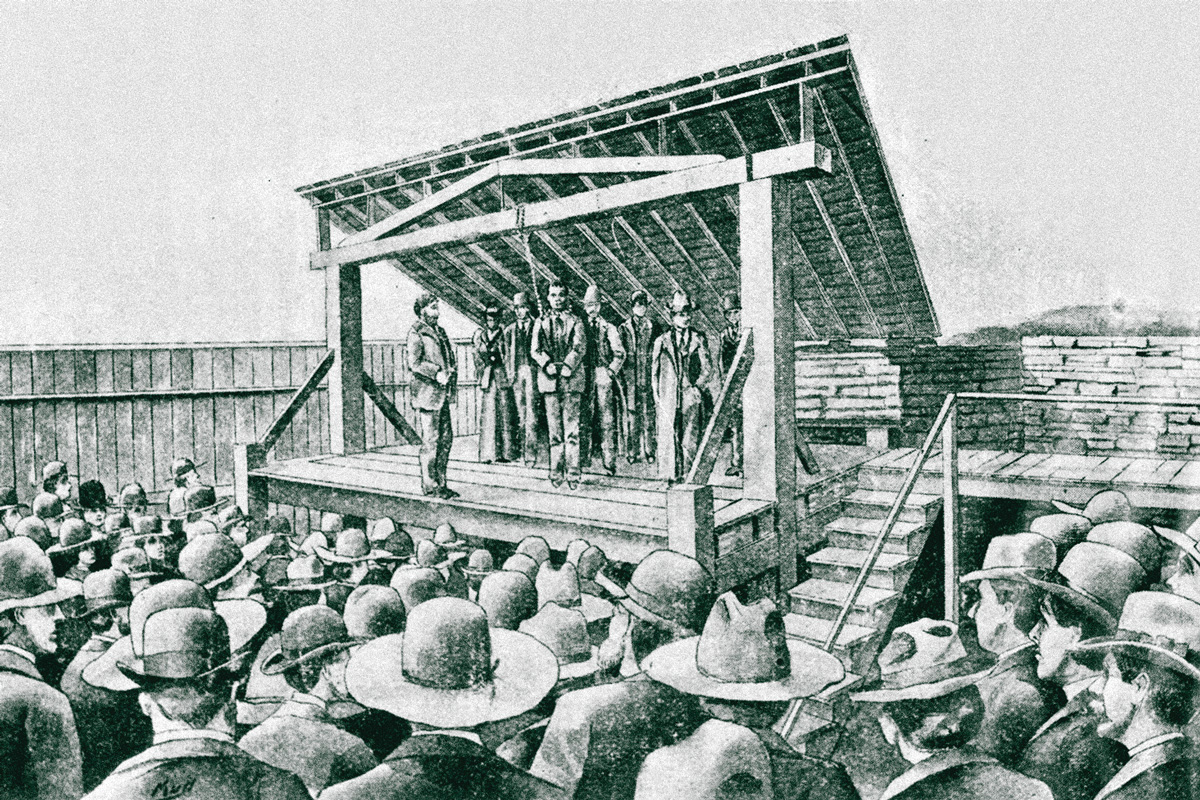

Epilogue

Cherokee Bill was executed for crimes committed in the Indian Territory at the federal jail at Fort Smith, Arkansas, on March 17, 1896.

Cherokee Bill’s family took his body to Fort Gibson where a wake and funeral were held in the old military commissary building. He was buried in the Cherokee National Cemetery in Fort Gibson, later named the Citizens Cemetery of Fort Gibson, not far from companions Jim French and the Verdigris Kid. Some of the most important Cherokee citizens in Indian Territory history are buried in this cemetery, along with Cherokee Bill, his mother and siblings. In the 1990s, a headstone was placed on their gravesite with incorrect dates for the children. It listed Cherokee Bill as the youngest.

The saga of Cherokee Bill comes to a close, but the outlaw legend from eastern Oklahoma lives on. He was like a shooting star that shines real bright for a short period but then quickly flames out. If Jesse James, Butch Cassidy, Billy the Kid and the Daltons can be celebrated as American outlaws, there is no reason we cannot also celebrate the dashing firebrand Crawford Goldsby known as “Cherokee Bill.” What is known is that Cherokee Bill’s outlaw legacy remains forever in the annals of frontier Oklahoma history.