Fact or Fiction?

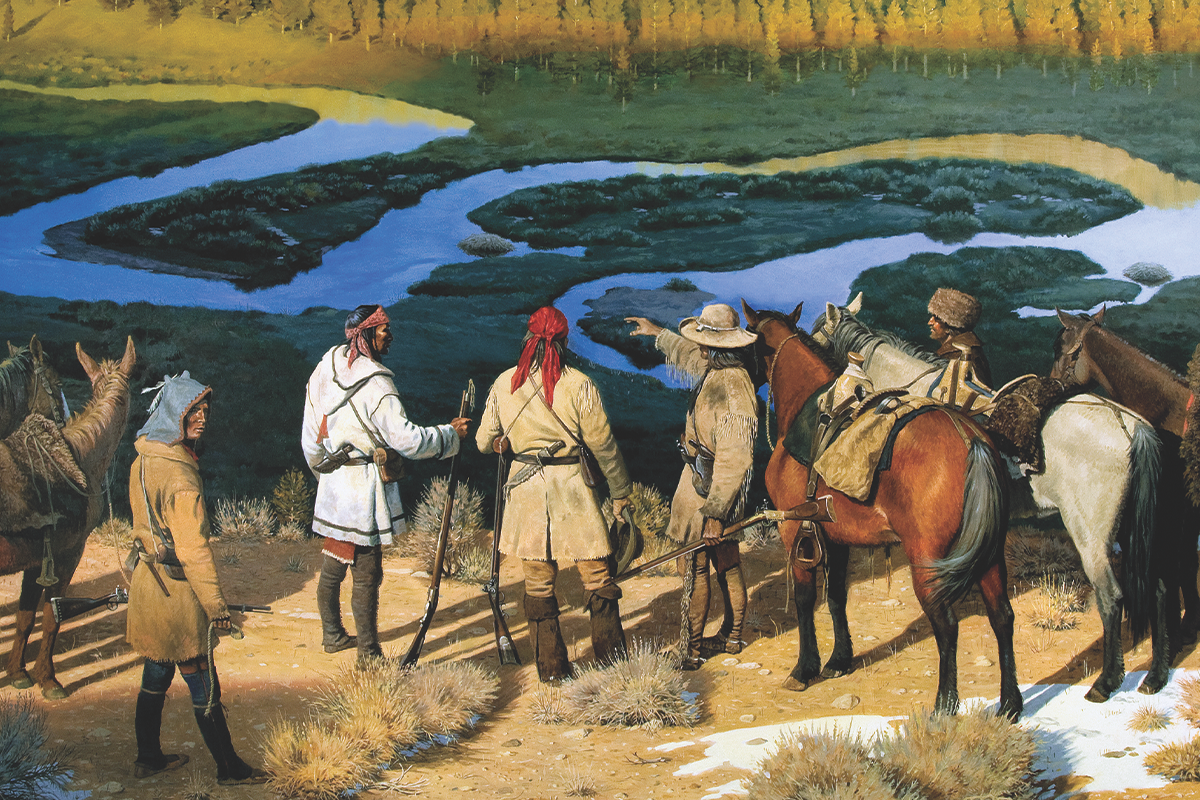

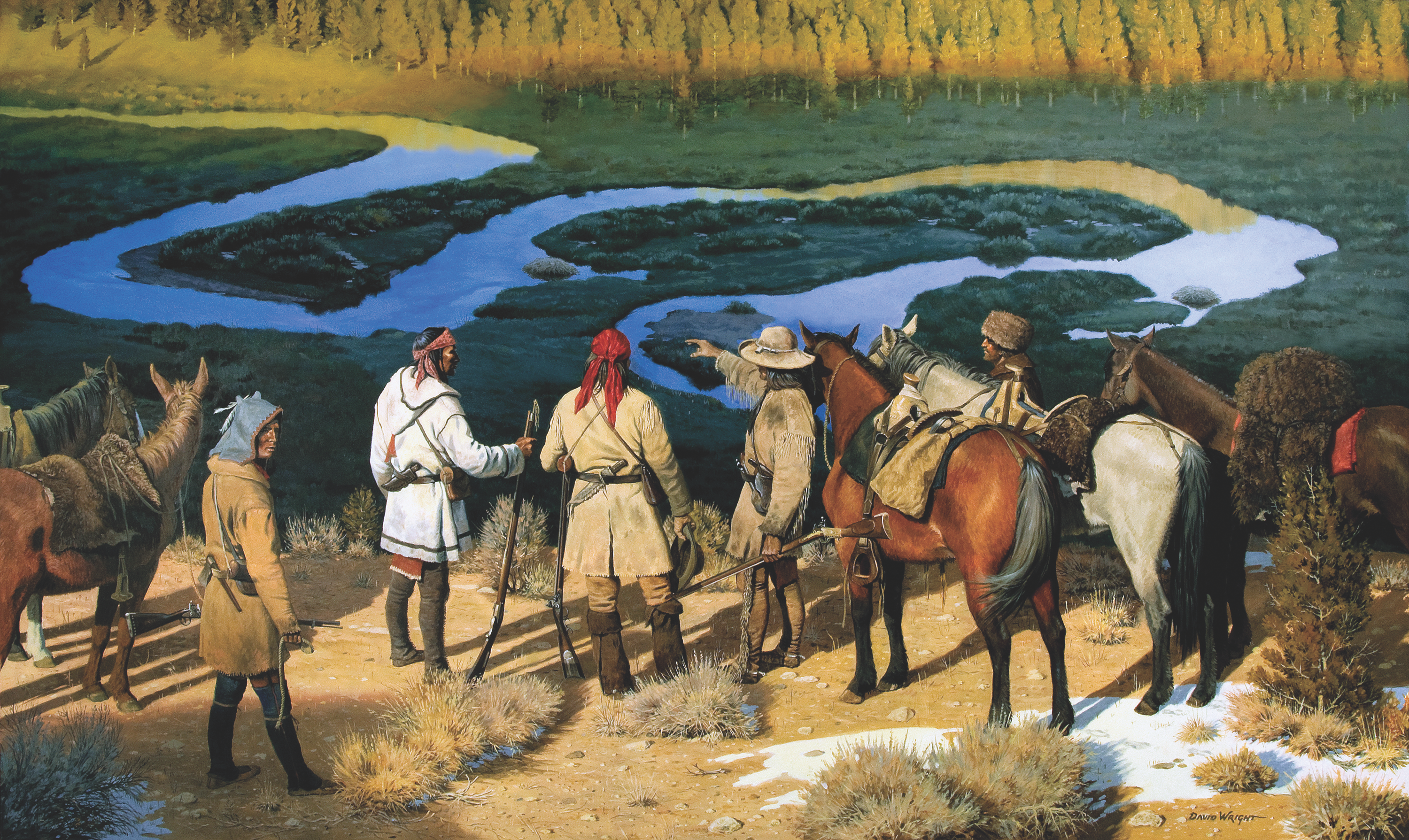

Did America’s first frontier hero reach the Big Sky land of geysers, scalding springs and “putrefied” trees that John Colter saw and Old Gabe and Black Harris yarned about?

Rumors abound of Daniel Boone’s treks to Yellowstone and beyond, even to Idaho and the Pacific. Recent writers hinting of these far-off forays can be vague on details, creating hybrid revelations taken as gospel. Two years past Boone’s death’s bicentennial we will revisit the most credible of these stories, placing them in the setting of his trans-Mississippian realm that by 1820, when he was buried near La Charette, Missouri, was already vanishing.

Twenty-five miles upriver from St. Louis village—a bustling fur hub dominated by two French half-brothers, Auguste and Pierre Chouteau—and west of Alton, Illinois, Boone and seven families, a few of the enslaved and a passel of livestock forded the Father of Waters into Spanish Upper Louisiana. Like Cumberland Gap to the east and South Pass to the west, this shallow oxbow of the Mississippi was destined to become the western portal for the thousands soon to tread in his wake. The year was 1799. Daniel Boone, at 65, was starting over.

He and his wife, Rebecca, hied to 850 acres of fertile bottomland past the village with its beaver bales, hide men and motley coureur de bois and over the Big Muddy from King’s Road—New Spain’s 40-mile hike back to St. Louis—to live with their son Dan Morgan at what is now Matson. Here the paterfamilias acted as syndic—Justice of the Femme Osage District—famously settling disputes under his Judgement Tree, claiming land and blazing Boone’s Trace.

Boone hunted and trapped the Niangua and Osage (and Marmaton, a Little Osage branch), Gasconade and the Meramec’s tributaries clear to the expat Shawnee towns. Samuel Coles saw him on the Lamine—“he caught two beavers. Their skins were worth nine dollars…at St. Louis.” A warrior band of hide-hunters, Sacs maybe, nearing his winter camp forced him to hide for 20 days, kindling fire only at night to cook. “He never felt so much anxiety in his life for so long a period,” he told John Mason Peck, an early biographer.

Beaver was king. To harvest them, a typical mountain man, a “company man,” say, for the firm of Smith, Jackson & Sublette, toted six heavy hand-forged double-long spring traps. Boone packed no less than 12. Stephen Hempstead watched as the colonel, his son-in-law and Derry Coburn, Dan Morgan’s teenaged slave, landed his wide, fur-laden canoe draped in bear hides to shield a fortune in peltry from the sun and rain at St. Charles’s wharf.

He landed first the stern and the sterns man got out and then the bowman rowed her around …to not disturb the cargo—the middle being full and covered. Flanders Callaway and the Negro rowed in front and Boone steered in the river. The value of their furs and skins was considerable. It was their practice to go by themselves or with Negroes every winter to hunt—even after their friends were opposed to it—and Boone, I should suppose, to be eighty years of age or upwards.

Osages spied him nearing Kansas’s border with Dan Morgan, Nathan and Derry. The Boones got 900 beaver and considerable otter, fleshing out the beavers and saving their castors for the perfume trade and for lure and lacing their skins on willow hoops. They pulled the case-skinned otter fur-side out down the narrow stretcher boards planed thin and tapered; once dried, they bundled the furs in half-grained bearskins and buried them. After the Boones trapped on down the Bourbeuse, the Osages raised a cache with 100 lush plews.

A year later the tall, proud Osages—shaven heads a-glitter with sterling earbobs, and tawny with ocher and bear fat and crowned with flamboyant yellow and black porcupine-quilled roaches—saw the aging buckskinned deer-slayer astride a pony, alone but for the Black teen who fled as they charged, jerking Boone from his saddle and out of his capeau and acting as if to whip him. When they reset their ramrods, Boone put Derry to cooking, as he and the Osages, striking flint-and-steel for their catlinite disc pipes, palavered by sign. He knew what they wanted.

After filling their bellies, powderhorns and shotbags, the Osages scarfed up the pelts and left, one of them in his new blanket coat. Boone backtracked to unearth a tiny cache of DuPont and stubby, finger-long lead bars to run the big .66 caliber balls he used and trapped on, hunkering by day, kindling fire by night. That spring he packed home 200 beaver.

The Boones now lived west of their original Spanish grant with Nathan on Femme Osage Creek. In 1813 when Rebecca died, Daniel moved 20 miles to La Charette (Marthasville) beside his daughter Jemima Callaway and her husband Flanders. La Charette’s meat-getters took native wives and hired out to fur mogul August Chouteau, its blended community offering, said Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, the last Anglo society before Santa Fe.

Wrote Clark:

May 25th. Friday 1804—Camped at the Creek called Chouritte, above a Small French Village, settled at this place to hunt, & trade with the Indians.… People at this Village is pore, houses Small, they sent us milk and eggs.… This is the Last Settlement of Whites.

Two years later, the Corps huzzah’d “the French Village Charriton”:

Saturday 20th Septr. 1806—…Saw cows on the bank which Caused a shout to be raised for joy.… French and Americans express great pleasure at our return, and acknowledged themselves much astonished… we were Supposed to have been lost long Since.

Neither man mentioned Boone. Nor did Zeb Pike when he visited July 1806 to dine with Joe Chartran—La Charette’s syndic—and his Osage wife. From this redoubt—the cutting edge of America’s frontier—Boone launched his last hunts. His knowledge of the West was vast. Besides local hunters, he knew James Mackay, St. Charles’s syndic. Mackay’s treks bisected Canada to the Rockies; he canoed with Hudson’s Bay; he mapped the Missouri to the Dakotas; Lewis and Clark used his maps. Senior pathfinders Boone and Mackay surely swapped notes on the West—the day’s most urgent topic.

Territorial Governor Clark was Boone’s friend, as was John Colter—the renowned Corps hunter Manuel Lisa hired to go to the Tetons. Colter mustered at La Charette with Nathan’s Rangers and Nathan named a son for him. Forrest Hancock, who trapped with Colter then pushed past the Platte with Joseph Dickson and Pierre Menard, lived a mile away. Daniel Boone visited Forrest’s father from Boonesborough, William, whose land bordered his son’s.

Wade Hays said Grandfather Boone learned about the West from “talking with Indians,” like the Shawnees who ranged “to the Three Forks of the Missouri and beyond,” Bernard DeVoto describes in Across the Wide Missouri. He visited Jimmy Roger’s Shawnee town near the Meramec to hunt with his native brothers of old and reminisce. Nathan hired Rogers’ sons for Army guides. Charles “Indian” Phillips, who ramrod-whipped Simon Kenton in Ohio land and captured Daniel in Kanta-Ke, became his Far West camp-mate.

As I write in The Hunters of Kentucky: “The old hunter’s grandchildren remembered Phillips as being ‘tall and spare,’ and that he ‘wore Indian leggings and moccasins’ and ‘walked and acted like an Indian.’ ‘All were afraid of him.’ Maybe. But for old Sheltowee—Boone’s adopted Shawnee name—feeling his age and rheumatism and the worries Kentucky wrought a fading memory, Phillips the Shawnee was the perfect comrade.”

Boone had hunted the Missouri past Kansas, maybe to the Platte, and knew what lay past it. He had kith and kin, a Shawnee and slave for camp-hands, and La Charette’s hide-hunters to contract with. In 1890, historian Lyman C. Draper, the State Historical Society of Wisconsin’s secretary, corresponded with Wade Hays, Boone’s great-grandson, who wrote that Boone and his father, William Hays Jr., hunted the Yellowstone from 1808 to 1809:

Col. Danl. Boone, Wm. Hays Jr., Derry the Negro, & several others were along. Started in the fall of the year–& returned…spending one whole year—& two winters hunting. Went near the junction of the Yellow Stone &…perhaps the Clark & Lewis Rivers…Had good luck—got some Mackinaw boats—& started homewards with the furs. In the act of landing Indians attacked them from the river…. Thinks they were Snake Indians—& landed & camped for the night with sentinels. But they were followed no longer …. Indians robbed the beaver traps & leaving their traps, hoping to repeat the procedure.

In recalling this episode of 82 years before, Hays names people and rivers, “Mackinaw boats,” tribal affiliations, times and seasons. Adding to his credibility, his tale is told simply, without bombast or romantic nuance, but his dates conflict with factual events in Boone’s life that occurred within the same two-year span.

Like:

1) Daniel, William Hays and Derry Coburn trapping near now Lexington, Missouri, came upon an Osage hunter who, through sign language, “invited Boone & his party to his camp.” Darting ahead as decoy, the Indian alerted another “twenty or thirty” warriors who charged, forcing Boone’s party to gallop off leaving traps and peltry behind.

2) Boone, beset with scrofula’s fever, oozing neck sores and lymphatic swelling, was in St. Charles under the care of Dr. John Jones, husband of Daniel’s granddaughter Minerva, who was treating his lesions with calomel, a mercury-laced balm.

3) During his medical stay, Daniel dictated his memoirs to Dr. Jones so “that his own words might be left in the hands of a true and trusted friend, penned strictly in accord with his dictation.” Jones was later murdered by rustlers who stole Boone’s manuscript from his buggy.

4) Boone wrote to Judge John Coburn, formerly of Kentucky, concerning his land claims.

5) Boone petitioned the U.S. Congress for remuneration for his loss of 10,000 acres.

Other issues: Snake Indians—a loose grouping of Bannocks, Sho-shones and Goshutes—rarely fired on armed Americans and bypassed the Yellowstone, land of the Blackfeet and Crow, Northern Cheyenne and Arikara. Further muddling matters, biographers have bastardized Hays’s quote, cutting and pasting in unrelated stories—like that of George Stoner’s, who got to the Big Sky country but without Boone, he says—to craft creatively skewed fabrications now in print.

Draper shelved Wade Hays’s story. In truth, it was not new to him. He’d corresponded years before with H.A. Logan, Jr. about Boone’s “last and most noted adventure…the Yellowstone trip”—with his late father Henry.

There were about a dozen in the company: Col. Boone, Alex. McKinney, Henry Logan and others. They started July 1817 and returned the next summer. They were attacked several times. Indians besieged their camp but…a snowstorm came up and the Indians raised the siege. They were attacked again as they descended the Missouri…[and] forced to anchor on the opposite shore… Boone ordered the company on board and they moved past the Indian camp. A great many valuable furs were secured.

H.A.’s letter has it all: weather, dates, raids and people like Alex McKinney, a La Charette hunter-surveyor who served in Missouri’s assembly. Draper doubted that Boone at 82 was traversing the Far West in the winter. Could it have been 1814?

“No,” said H.A. “My father served as a substitute in the War of 1812, so it was after that…probably the winter of 1815-16.” He admitted his “scattered fragments of memory” seemed as “faint recollections of a half-forgotten dream,” confessing he’d “mixed up” some of his father’s hunts—“The Salt River, The Grand River, The Osage and Yellowstone expeditions.”

Draper told H.A. of his talks with Nathan Boone who “sd. nothing about the Yellowstone trip.” If it did occur, “it might have taken place in abt. 1814, while Indians were hostile,” Draper mused, referencing the 1815 Portage des Sioux Treaty William Clark and Ninian Edwards (governors of Missouri and Illinois Territories) mediated with a dozen Midwestern tribes; the truce slowed raids along the Big Muddy and animated Western expansion while marking a step in the death march of native lifeways.

“As I stated before, I told you all I knew concerning the trips in which my father accompanied Col. Boone. I know nothing more that can be of interest & shall draw this reply to a close,” H.A. said, ending his interrogation by mail.

Draper tabled Logan Jr.’s story as he did Hays’s. Little of it pertained to the Yellowstone and Indians harassed travelers up and down the Missouri. And, Nathan and his daughter Delinda, he knew, distrusted Logan Sr.’s “telling tall stories” to inflate his role in Daniel’s exploits.

Draper never resolved the Yellowstone matter. Through it all, Nathan, though, is an intriguingly reliable source, though he omits key events in his father’s life; maybe because his was not a selfie culture and, like Daniel, he loathed boasting. A clue to this tale’s closure may lie in his own recounting of his father’s 1816 hunt (verified in the Niles Register in an April 29th letter from the Missouri Territory) when Daniel and “a noted woodsman by the name of Indian Philips” visited Fort Osage for two weeks.

We have been honored by a visit from Col. Boone.… The Colonel can’t live without being in the woods. He goes a hunting twice a year to the remotest wilderness he can reach; and hires a man to go with him, whom he binds in written articles to take care of him and bring him home, dead or alive. He left this [morning?] for the Platte.

Boone said he wanted to take “two or three whites and a party of Osage, and visit the salt mountains, lakes and ponds, and see the natural curiosities of the country along the mountains. The salt mountain was about 5 or 600 miles west of this place.” From Fort Osage, up Big Muddy and the Grand they canoed in search of beaver but “Indians and French trappers had caught them pretty much out.” When Boone took sick en route to the Platte, they paddled south to Fort Leavenworth, a day north of Kansas City, where he convalesced and met Capt. Bennett Riley.

Did this, his last far western trek foiled by sickness, mark Boone’s stab at the Yellowstone? Perhaps. Or did he get there, but Hays and Logan got the dates wrong? Maybe. We all want that Alfred J. Miller oil of him and Colter hunting griz on the Yellowstone or standing a’kilter to Old Faithful’s steam plume—hands high, mouths agape. One day, maybe, his lost memoir he dictated to Dr. Jones will surface at Sotheby’s and explain all. Until then…

The old hunter died in his 85th year at Nathan and Olive’s amid an unbroken circle of prayers and hymns and holding Nathan and Jemima’s hands until they heard him say “My time has come”—a triumphal end to an abundant life. A legend in his day and in ours, his indomitable spirit that sought new frontiers, that confronted hardship with courage, is the legacy left by the America’s original pathfinder and longest hunting long hunter, Daniel Boone.

Ted Franklin Belue is a prolific frontier writer and 2021 WWA Spur Award winner, whose latest book, Finding Daniel Boone: His Last Days in Missouri & the Strange Fate of His Remains, was published in September 2020.