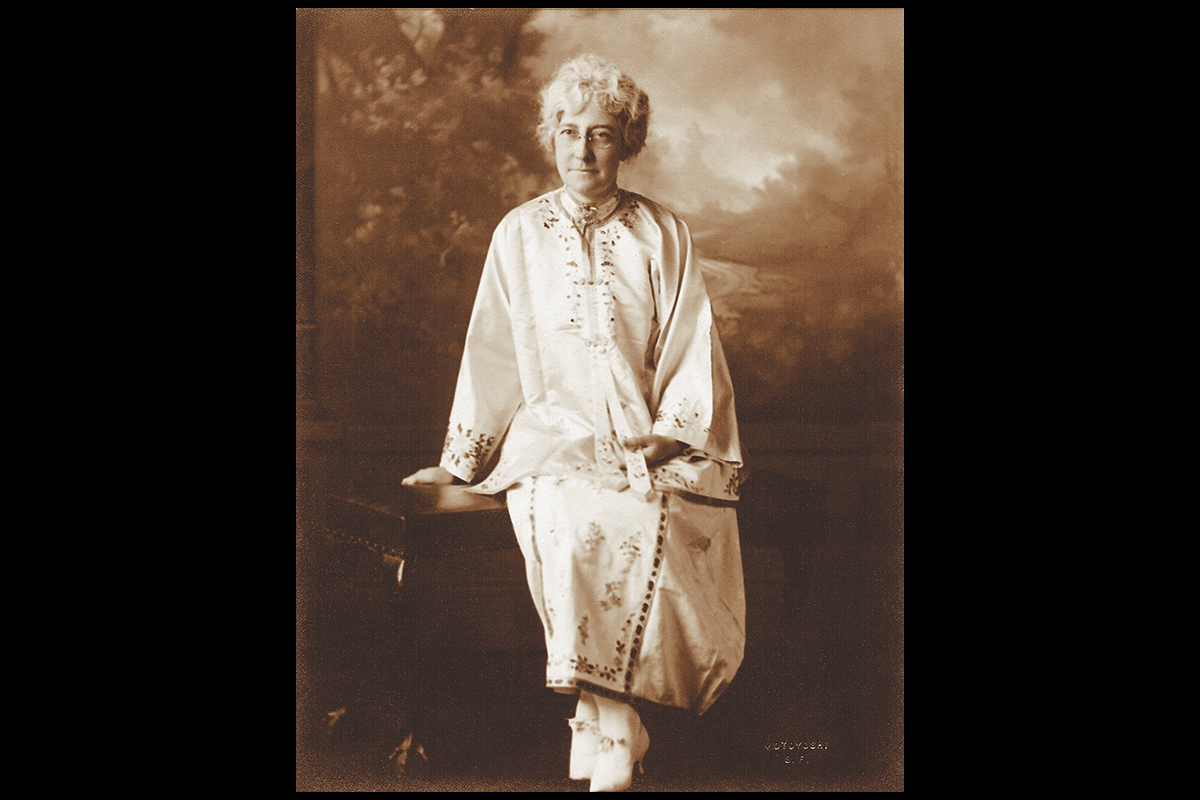

Chinatown’s Angry Angel never backed down from a challenge.

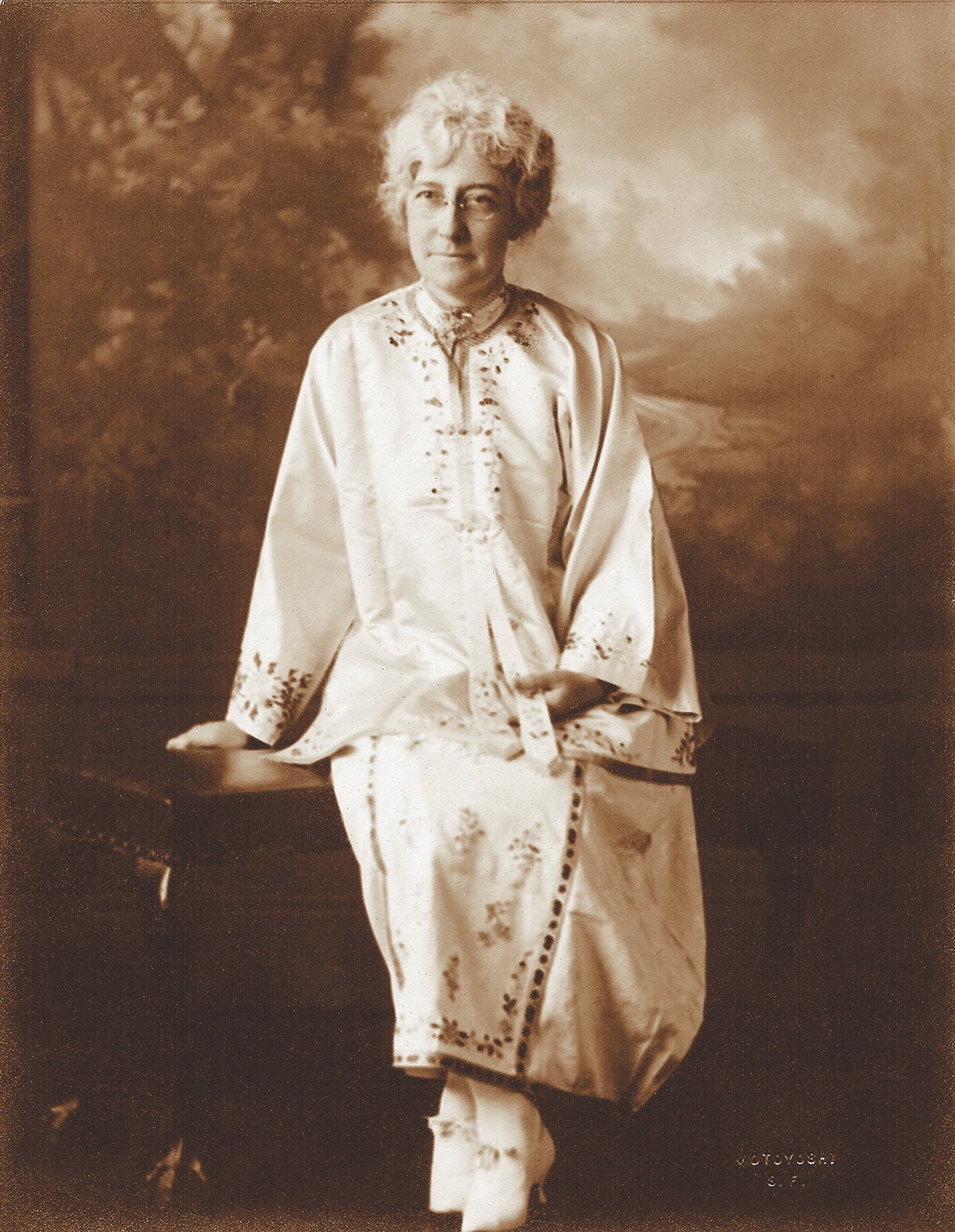

The girls she saved called her Lo Mo, Chinese for Beloved Mother; the men she thwarted called her Fahn Quai, the White Devil; and history calls her Chinatown’s Angry Angel.

Donaldina Cameron left a safe, cozy life as a young woman to take on a most remarkable and dangerous mission: From 1895 until her retirement 47 years later, this missionary waged war against the slave traders who imported Chinese girls to the United States for servitude and prostitution.

Historian Dorothy Gray calls her “perhaps the most active and daring freedom fighter in the history of the West.”

All photos courtesy Cameron House

These days, Cameron House exists in San Francisco’s Chinatown as a center to help low income emigrants and families. But in its early years, it was a safe house for girls and women who had no hope in life, who would be enslaved or raped until they died. Cameron House offered them a haven, and this tall, dignified woman fought for them like a mother hen.

Over her long career, Donaldina is credited with saving an astonishing 3,000 women and children.

Chinatown’s “Fearless” Angel

Donaldina was only three years old when a campaign began that would shape her life. In nearby San Francisco, Protestant women launched an attack on “yellow slavery” in 1873, the same year the cable cars first climbed San Francisco’s hills. But Donaldina wouldn’t even know this problem existed until she was 25, when a friend’s mother begged her to help the cause. Until then, Donaldina had always expected she’d marry and have a family, and live the kind of comfortable life her Scottish-born parents had always provided.

She found herself intrigued by stories of the mission where young girls were given safe haven, and she was impressed by the courage of the mission’s founder, Maggie Culbertson. When she was told Maggie’s health was failing and she desperately needed help, Donaldina agreed to donate her time for a year. She thought that she’d only teach the girls sewing and other useful skills.

She arrived in San Francisco in April 1895 and was quickly launched into her life’s work. Just 18 months later, Maggie died, leaving Donaldina to assume a role she had barely begun to learn.

For many in rough, garish San Francisco, the Chinese slave trade was as much a part of their history as was the gold rush. The latter had created the former—as Chinese men rushed to California to seek their fortunes, they longed for wives and pleasure girls. Soon, traders were traveling to China, where they’d offer families money for their daughters, who were supposedly going to America to find husbands or to get an education. Instead, the girls—some as young as five years old—were sold into prostitution or became domestic slaves. The underage females who were prostituted didn’t last more than a few years before their worn and abused bodies gave out—and those on the verge of death were put in a solitary room to starve.

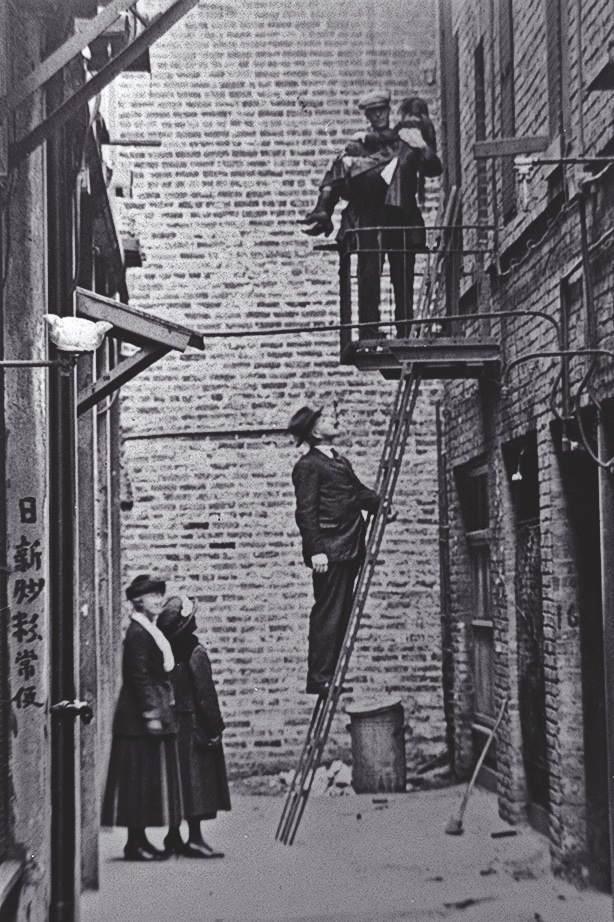

Freeing them was dangerous work. Even though Maggie Culbertson received help in running the mission, she always did the rescues herself, a job that Donaldina now embraced. She found herself in the worst hellholes of Chinatown, sneaking to avoid detection from the tongs who controlled the slave trade and often threatened her and her mission with death and destruction.

The girls were kept under strict guard and were warned that outsiders like Donaldina were devils. Besides, their lack of English skills or knowledge of their strange new city kept them locked in their torturous worlds.

By all accounts, Donaldina was fearless in challenging this dismal situation. She brought police to the doors of prostitute “cribs”; she climbed ladders and ran over rooftops and crawled into hidden rooms; some say she even wielded an ax to break down doors.

The law wasn’t always on her side. Since child protection laws were nonexistent until the early 1900s, getting legal custody was almost impossible. Tong leaders would claim a girl was a relative, or that she was working voluntarily, and as her “sponsor,” they had a right to their property. The courts often agreed, compelling Donaldina to occasionally break the law to save the girl.

She realized early on that her best strategy was to nab a girl and work out the legal problems later. At least then, the girl would be safely tucked away in the mission house while the courts hashed out the details. In 1904, she had her attorneys challenge the courts to provide for child welfare laws—a breakthrough that would provide her a most useful tool for her rescues.

At the safe house, girls learned sewing and cooking, they were educated and they were encouraged in the arts. The house was also the site of many happy marriages of girls who eventually found worthy men. Some of the girls opted for more education, and one of Donaldina’s “daughters” became the first Chinese woman to graduate from Stanford University. Another daughter trained to become the first Chinese nurse through the Presbyterian Hospital in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Yet other daughters stayed on at Cameron House to help with the mission’s work.

Donaldina found allies in the large Chinese population that detested the slavery as much as she did—these friends were often her eyes and ears to find victims who needed saving.

Throughout her career, she kept expanding her work—founding a home in Oakland, California, for babies and raising awareness about widespread prejudice toward all Chinese. For instance, she tried to overturn the Oriental Exclusion Act, which prevented Chinese from owning property, limited where they could live and denied them the right to testify on their own behalf in an American court.

Donaldina pleaded with religious leaders from throughout the West to fight against such prejudices, but she was rebuffed with the scolding that “politics was not her business—competent professional men would handle worldly problems,” according to the book Chinatown’s Angry Angel by Mildred Crowl Martin. But Donaldina never gave up the fight that would eventually see those discriminatory laws erased from the books.

Donaldina retired in 1942, and three years later, adopted a Korean orphan. She died in Palo Alto, California, in 1968, but her memory lives on in the house that bears her name and a life’s work that saved so many.

If you call Cameron House today, the phone is still answered in Chinese.