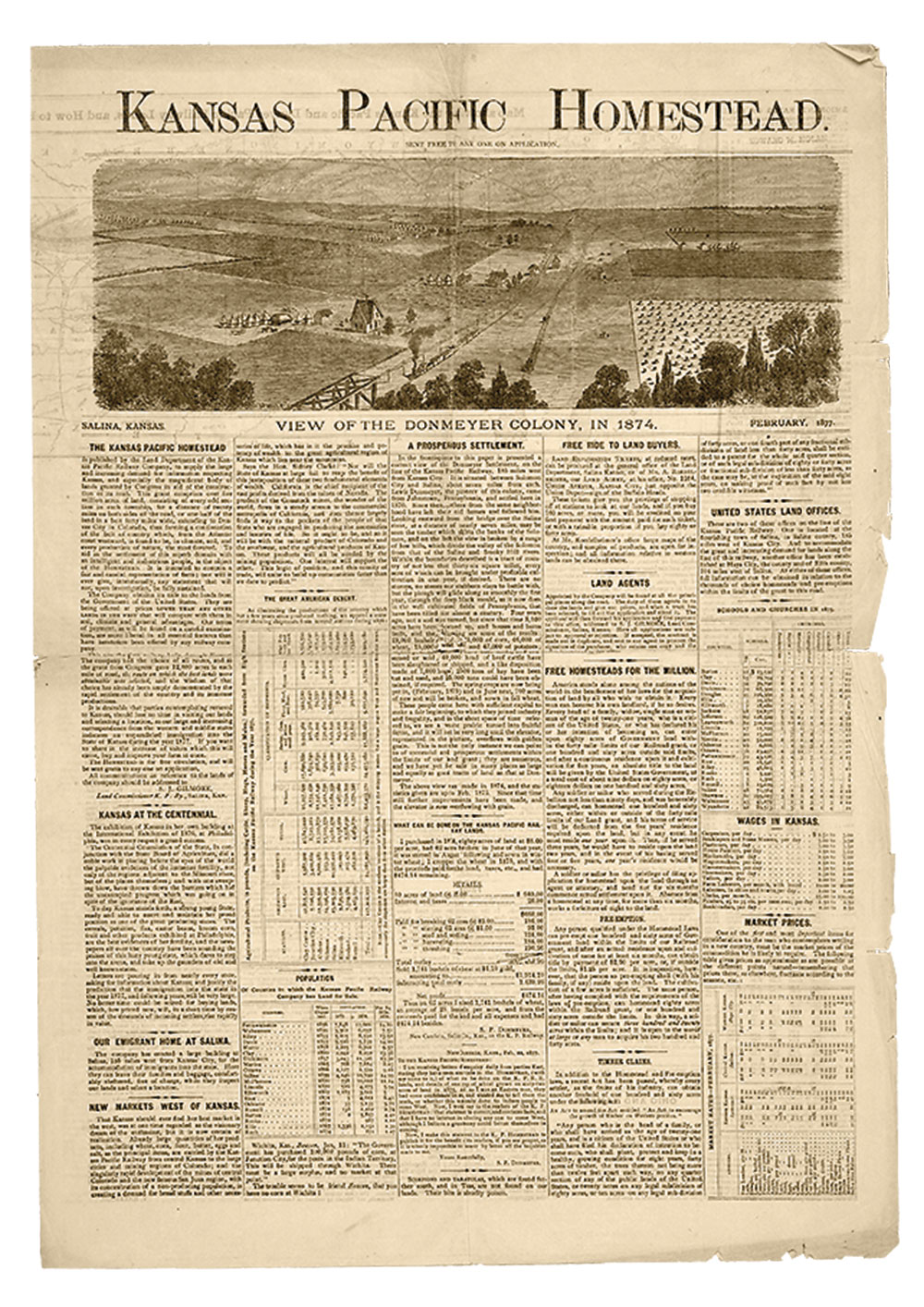

– Hannibal Bridge Photo Courtesy NYPL Digital Collection/KPRR Handbill Courtesy Beinecke Library, Yale University –

The American West and American rail-roads are filled with myths and legends. Some of them have been debunked, or at least questioned—like William F. Cody’s reputed buffalo-hunting contest against William Comstock near present-day Oakley, Kansas. Others are generally accepted, like the linking of the coasts by rail when the Central Pacific and Union Pacific met in Utah in 1869 to complete America’s first transcontinental railroad.

Often overlooked in both of those events is the role played by the Kansas Pacific Railway, which made a lot of Old West history.

The Race West

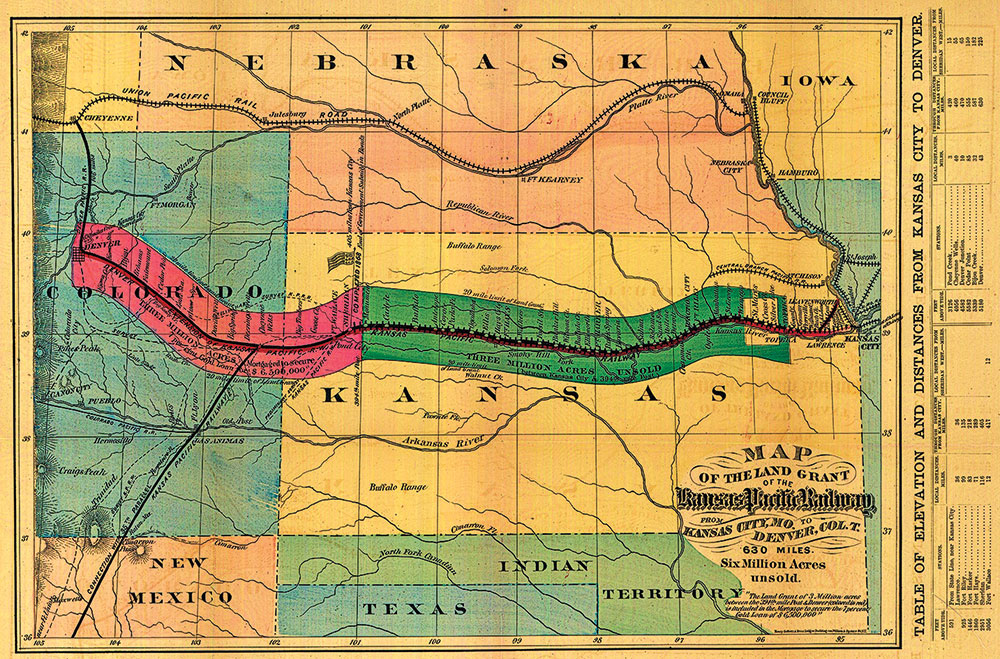

The KP had its origins in 1855, when the Leavenworth, Pawnee & Western Railroad was chartered. In 1862, President Abraham Lincoln’s signing of the Pacific Railway Act left the LP&W eying transcontinental glory, and in 1863, the LP&W had a new name, the Union Pacific Railway, Eastern Division, though it had no connection with the UP that was laying tracks west from Omaha, Nebraska. When the Pacific Railway Act was revised in 1864, granting westbound construction of the transcontinental railroad to the first company to reach the 100th meridian, the race was on. Yes, the Union Pacific won the beefy contract, but the railroad that became the Kansas Pacific Railway in 1869 kept making history.

While the railroad’s groundbreaking began in Wyandotte (now part of Kansas City, Kansas), the Missouri side of the city still honors its transportation history (Arabia Steamboat Museum, National Airline History Museum, 1914’s Union Station). By November 1864, the rails had reached Lawrence, and that helped the city burned by William Quantrill’s raiders in 1863 rise from the ashes to become the vibrant, historic city it is today (Watkins Museum of History).

In June 1866, the tracks hit Junction City (Geary County Historical Museum) and neighboring Fort Riley (U.S. Cavalry Museum, Custer House), the railroad’s planned western terminus. But Denver wanted a railroad, too, and Coloradans’ voices were heard in Washington, D.C., where President Andrew Johnson authorized a railroad line—funded primarily by German investors—to connect Denver.

Kansas Cowtowns

In the spring of 1867, the iron rails put Abilene (Dickinson County Historical Society, Old Town Abilene, Abilene & Smoky Valley Railroad) on the map as a shipping point for Texas longhorns. “The first shipment was made on the 5th of September,” the Chicago Tribune reported on November 14. “On the 24th, 25,000 head of cattle were gathered at the station waiting shipment, and 10,000 more were on the way from Texas. Next season it is calculated that not less than 200,000 head of beeves will go to the Abilene market for sale and shipment.”

By autumn, the rails reached Ellsworth, 224 miles from Wyandotte, so when Abilene’s run as a cowtown ended in 1871, Ellsworth (Ellsworth County Historical Society Museum) was ready to take over. Two weeks after reaching Ellsworth, Hays (Fort Hays State Historic Site) had a railroad, too.

– Photos Courtesy Kansas Tourism –

Railroaders had to eat, and Cody kept their bellies filled with buffalo. In 1868, Cody said, he defeated Comstock, 69-46, in a buffalo-shooting contest. Did it happen? Biographer Louis W. Warren says no, at least not the way Cody claimed. In Memories of Buffalo Bill, Cody’s widow mentioned a poster offering Kansas Pacific excursions to the contest—but the railroad didn’t become the KP until March 3, 1869, not the only factual error in a book written with press agent Courtney Ryley Cooper. Historian Steve Friesen, however, notes that there’s enough archaeological evidence, and plenty of stories, to suggest some truthfulness to the legend. No matter your thoughts, the monument near Oakley is worth seeing.

Comstock didn’t live long enough to add his opinion. Indians killed James Fenimore Cooper’s grand-nephew, operating as a scout for the 7th Cavalry out of Wallace (Fort Wallace Museum), on the Solomon River in August 1868, the month the railroad reached Wallace County. There construction stalled until October 1869 while the newly renamed Kansas Pacific Railway looked for more money.

– Railway Brochure Courtesy Beinecke Library, Yale University –

Denver Bound

In March 1870, westbound rails entered Kit Carson, Colorado, and tracks started moving east out of Denver. Coloradans had been busy. The Denver Pacific Railway and Telegraph Company, incorporated in 1867, linked Denver with the Union Pacific in Cheyenne, Wyoming, in June 1870.

KP tracks from the east eventually reached Hugo (Limon Heritage Museum Railroad Depot in nearby Limon) and Deer Trail (Deer Trail Pioneer Historical Museum). On the morning of August 15, 1870, 10 and a quarter miles separated the KP’s end of track from Denver. A race began for the midpoint at Comanche Crossing. Railroad crews, headed by Major L.H. Echoltz, departed from Denver, and another left from the east under one E. Weed. “The Weed party won,” the Atchison Daily Champion reported, “completing their 5 1/8 miles at 12:30. The last rail was laid at 2:30 this afternoon.”

A marker commemorates the event at Lyons Park in Strasburg, née Comanche Crossing.

– Courtesy Colorado Railroad Museum –

Coast-to-Coast

The Kansas Pacific Railway formally opened on September 1, 1870. Passengers could leave Denver (History Colorado Center; nearby Golden’s Colorado Railroad Museum and Buffalo Bill Museum and Grave) and be in Kansas City, some 639 miles away, in 36 hours.

The railroad cost more than $23 million, the Nashville Union and American reported, adding: “The government has done less for this road than for the Union and Central Pacific Railways, only giving it a subsidy of about nine thousand per mile, when we average the whole distance of the route, and it is remembered that the last 200 and 34 miles was finished by private subscription.”

But there’s more to this story because what history calls the first transcontinental railroad, technically, wasn’t. Sure, the UP-CP linked Sacramento and Omaha, but the Missouri River separated Omaha from Council Bluffs, Iowa. Passengers and freight had to cross the Big Muddy by ferry or ice bridges to catch the next train. Not until March 22, 1872, did a railroad bridge link those burgs. But on June 30, 1869, a bridge over the Missouri connected the two Kansas Cities by rail.

Which means the KP completed America’s first coast-to-coast rail connection.

“The people of the United States, and particularly those of the West and South, owe a debt of gratitude to the directors of the Kansas Pacific Railway,” the Union and American continued, because “they have secured the most direct route from the Eastern Seaboard and the Southern States yet completed to the Pacific” and “have aided the people to become prosperous….”