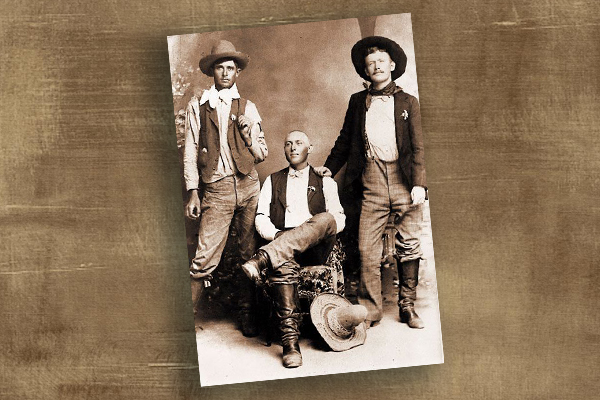

Wild Bill’s 1870 drunken brawl with Custer’s troopers is as legendary as the man of many names he killed.

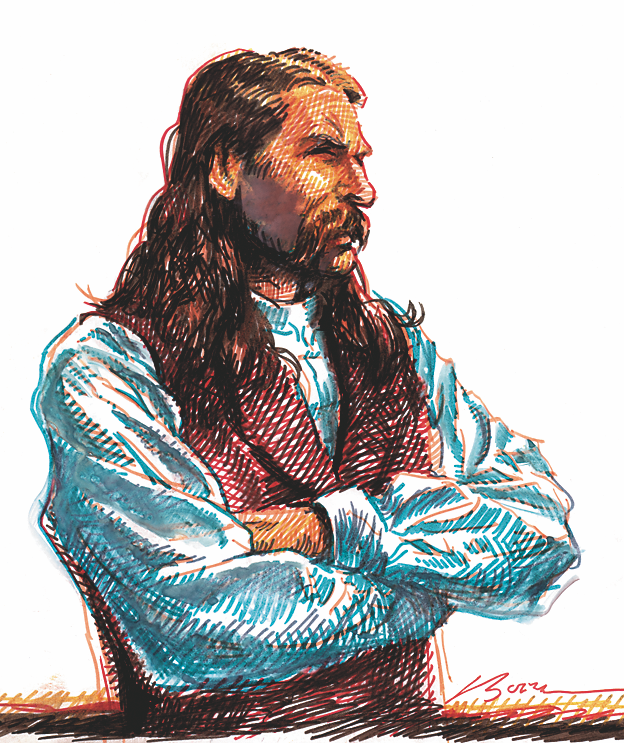

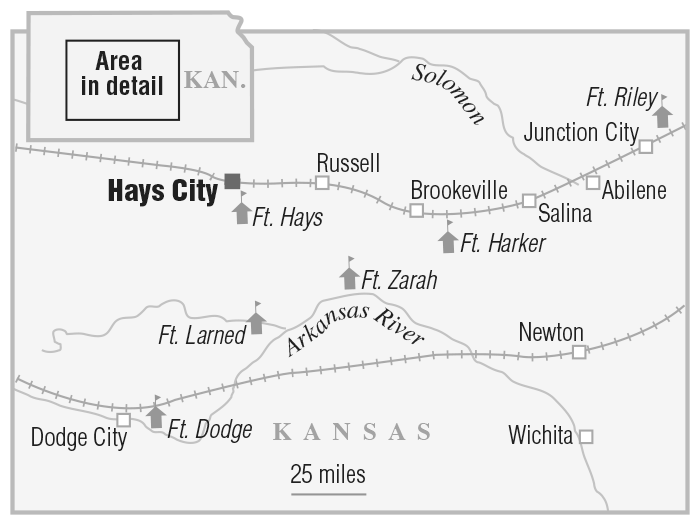

On July 17, 1870, Wild Bill Hickok had one whale of a brawl in Tommy Drum’s saloon in Hays City, Kansas. What makes this fight arguably Hickok’s most important is that he killed a trooper in Custer’s 7th Cavalry who had earlier been awarded the coveted Congressional Medal of Honor. The truth of the brawl and cavalrymen involved has only recently surfaced from military records in the National Archives. Biographers of Hickok injected so much fiction in recounting this brawl that the truth seemed forever lost.

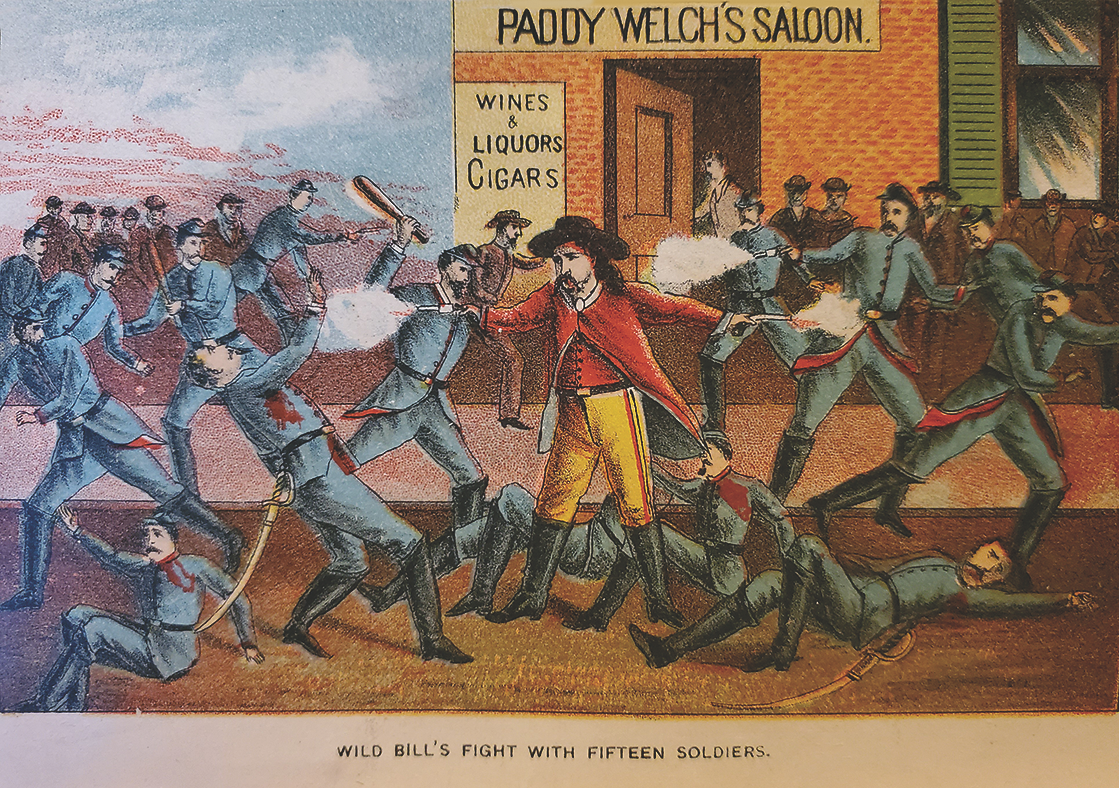

James W. Buel’s Heroes of the Plains (1885) produced a narrative wrong in every detail including saying the fight occurred in Paddy Welch’s saloon. Buel claimed Wild Bill’s widow gave him Hickok’s diary and thus the brawl is straight from Hickok. It started on February 12, 1870, as a fistfight in the street with a 7th Cavalry sergeant, but as Hickok was winning, 15 soldiers joined the fracas, pummeling Hickok until Paddy handed Hickok his pistols. Hickok then killed several soldiers and was wounded seven times and escaped across the Smoky Hill River—11 miles distant.

Later biographers followed Buel with certain emendations until William Connelley changed it to a different February date and said the brawl was caused by George Custer’s drunk younger brother Tom. A greater fiction could not be told. Connelley’s notes on his book, housed in the Denver Public library, cite the source as a letter written in 1926 by a man who was not even born when Tom Custer was alive. Eugene Cunningham also used this story in his popular book Triggernometry: A Gallery of Gunfighters (1934) and now the mighty legend became “fact.” It is all bunk.

Uncovering the Truth—Ryan’s Report

Joseph Rosa’s 1974 They Called Him Wild Bill gathered the first facts. Using military reports, Rosa identified just two cavalrymen involved in the brawl, John Kile and Jerry Lonergan. It happened on July 17, 1870, and not in the winter.

Kile was mortally wounded and died the next morning. Lonergan was wounded and spent weeks recovering in the post hospital. Rosa included an obscure Eastern newspaper account from 1909, giving the most detailed account of the row. It was written by John Ryan, an enlisted man in the same company as the brawling

soldiers, who said Kile had earlier served in Company M under the name John Kelley but had deserted in 1867 and shortly before the fight had re-enlisted as John Kile. When Ryan recognized “Kelley,” he went to George Custer to get his desertion absolved and transferred back to Company M, as he had re-enlisted in Company I. Because Kelley/Kile had important “meritorious papers” as well as a recent honorable discharge as a first sergeant in the 5th Cavalry, Custer approved Kelley/Kile’s transfer back to Company M. Shortly afterward, he was killed in the saloon fight.

Ryan’s memoirs said something new: at one point in the fight, Lonergan had Hickok pinned to the floor, and Kile took out his revolver, which had been hidden under his shirt, put it against Hickok’s head but it misfired. This allowed Hickok time to shoot his pistol behind him, hitting Kile in the wrist. A second shot to the stomach mortally wounded the trooper. A third shot struck Lonergan in the knee and Hickok escaped, knowing soldiers would soon be after him.

Ryan’s account is supported in the earliest extant documents. One is a diary of a teenage girl visiting relatives posted at Fort Hays that summer. Annie Roberts wrote:

In the middle of the night we were aroused by a man wanting a priest, Father Swembergh to go over to the town with him—for ‘God’s Sake’—that two men were shot. He went over— ‘Wild Bill,’ a celebrated Desperado shot them. One died this morning [July 18]—there were shots fired backwards & forwards across the bridge.

Company F Private Winfield Scott Harvey also kept a diary. He wrote on July 18: “Two soldiers were shot last evening in Hays City by Wild Bill Hickok. One died this morning and the other is badly wounded….” This confirms what the Rocky Mountain News reported July 20: “Wild Bill shot two soldiers of the 7th cavalry, in Hayes City, on Sunday night, last, while drunk.” Custer’s wife, Libbie, wrote of the brawl in Following the Guidon: “With the free hand the scout drew his pistol from the belt, fired backward without seeing, and his shot, even under these circumstances, was a fatal one.” George Custer wrote in Life on the Plains that the victims of Hickok’s deadly brawls included “one…being at the time a member of my command.” The earliest book mentioning the brawl was W. E. Webb’s 1872 Buffalo Land. He confirmed only two soldiers were involved and said a “musket” placed against Hickok’s forehead misfired, otherwise he would have been killed. These accounts confirm what Ryan wrote, including the claim of a weapon misfiring.

Ryan’s memoirs are themselves an interesting story. Only a portion of them were published in 1909, and they remained lost until early 2000 when a Custer scholar fortuitously acquired the typed manuscript and published them in 2001 as Ten Years in Custer’s Cavalry: A 7th Cavalryman’s Memoirs. Ryan served two enlistments under Custer and survived Custer’s defeat in 1876. His memory is not distorted by anything anyone else wrote unlike all other accounts of the brawl surfacing in later Hickok biographies. There is no reason to doubt him saying the brawl happened in Tommy Drum’s saloon. That Buel cited Welch’s saloon is reason enough to reject it, since every other claim he made about the brawl was unadulterated fiction.

Who was John Kile?

Additional records in the National Archives support Ryan’s account and tell us much more about the soldier killed, John Kile. When a soldier died, his company commander issued a Final Statement explaining how the soldier expired. There are two such papers on Kile. The first simply said he died July 18 of a gunshot wound in Hays City. It was sent back from department headquarters asking whether Kile died in the line of duty. Captain Myles Keogh, who died with Custer, commanded Company I, the company Kile initially was assigned to (exactly as Ryan reported in his memoirs). Keogh wrote a second statement, noting Kile died in a “drunken row” in Hays City and not in the line of duty. But more importantly, he noted: “Private Kile (alias Kelley) was originally a deserter of Troop M of this regiment, and on re-enlisting was assigned to Troop I but attached and doing duty with Troop M at the time he was killed.” This important statement shows that Kile and Kelley were the same person, just as Ryan said.

Company muster rolls show in 1867 Kelley (who is really John Kile) and Ryan, both corporals of Company M, together deserted on the same day in June, while Custer’s men were camped near Fort McPherson in Nebraska during Custer’s first Indian campaign. Ryan’s memoirs do not mention his desertion. Turning himself in weeks later, Ryan was court-martialed and, in his defense, he stated on the morning of his disappearance he was filling canteens in a distant stream but got lost returning to camp due to a dense fog. This was confirmed by his company commander, and Ryan was exonerated. The likely story is that Ryan and Kelley/Kile left camp the night before and visited a nearby “hog ranch,” as Custer camped a few miles from the post the night before the dense fog. This is confirmed in the Itinerary journal of Lt. Henry Jackson. The fog disoriented the two corporals and the command left without them.

Kelley/Kile went to St. Louis, and on July 24 enlisted into the 37th Infantry as John Kile. His new company was assigned to New Mexico where his company C constructed a camp later named Fort Lowell. On Christmas Day 1867, Kile was arrested by his first sergeant for being drunk and stealing goods from the sutler’s store. He was confined and court-martialed. Found guilty, he was given a dishonorable discharge and ordered to serve three years hard labor at the Jefferson City, Missouri, federal prison. He escaped in June 1868 while being escorted. He went back to Tennessee where he had earlier served when he first enlisted in the 5th Cavalry on December 9, 1865, but deserted on November 20, 1866. He re-enlisted three days later as John Kelley and was assigned to the newly formed 7th Cavalry. Now back with the 5th Cavalry, Kile was court-martialed for desertion and found guilty—he never mentioned his stint in the 7th Cavalry as John Kelley—sentenced to a year of hard labor but not discharged. Four months were erased for voluntarily surrendering. At the conclusion of that he served under Brevet Maj. Gen. Eugene A. Carr in the winter campaign of 1868, when Custer’s 7th Cavalry had its November 27 victory against Black Kettle’s Cheyenne village on the Washita in present-day Oklahoma, with Ryan participating. Carr’s command was soon sent north to Fort McPherson in the spring of 1869 and participated in the Republican River Expedition, sent to punish Dog Soldier warriors who had raided north central Kansas in late May. That campaign ended in the destruction of Tall Bull’s village at Summit Springs on July 11.

Three days earlier Kile, along with two other soldiers sent in search of an abandoned cavalry mount, had a brisk fight with more than a dozen warriors who thought they could easily kill the men caught miles from their command. Instead, several warriors were killed, most wounded and the men escaped to report Kile’s heroics in saving their lives. He received the Medal of Honor on August 24, finished his enlistment and was discharged as a first sergeant May 17, 1870. His discharge papers noted his excellent character.

On June 2, he enlisted as John Kyle in the 1st Infantry in New York—his citation for the Medal of Honor misspelled his name as Kyle—but he deserted the next day and then appeared in Chicago June 9th and enlisted back into the 7th Cavalry as John Kile. He must have recognized an officer in New York who knew of his earlier dishonorable discharge in the 37th Infantry. It is the best explanation for his desertion after only one day. Both the June 2nd Kyle and the June 9th Kile enlistment papers have written on the back that he ended an earlier enlistment in the Company M, 5th Cavalry. Hence, both Kyle and Kile are one and the same. And so is the Kile/Kelley persona noted in Keogh’s statement after Kile’s death. Further, his 5th Cavalry court-martial confirms his initial enlistment in 1865 as a teenager. Thus, it is the same soldier who had four enlistments in five years, under three names, three desertions, two court-martials, one dishonorable discharge and escaped prison sentence, and one final hell of a fight with Wild Bill Hickok.

In an amazing twist of fate, the very day Kile was shot, 84 new recruits arrived by train. One was Frederick Thies, who was also assigned to Company M. Had Kile not been killed by Hickok, Thies would have recognized him the next day as the 37th Infantry soldier dishonorably discharged who escaped a three-year prison sentence. Thies was Kile’s company first sergeant who arrested him on Christmas Day 1867 and testified against him at his New Mexico court-martial. When Thies’ 37th Infantry enlistment expired he re-enlisted and was sent to the 7th Cavalry. But he never knew the man shot that first night in the 7th Cavalry was the same man court-martialed in his 37th Infantry company in 1867.

And now we know the details of the man killed by Hickok, shot in Tommy Drum’s saloon the night of July 17, 1870. Kile was a brave soldier who unfortunately stumbled across the path of Wild Bill Hickok and lost. Had his pistol not misfired, today we likely would not know a man called Wild Bill. And that is why the July 17, 1870, fight is the most interesting of all of Hickok’s gunfights.

What happened to Jerry Lonergan?

Military papers in the National Archives show Jerry Lonergan was a baker from Cork, Ireland. He enlisted at New York City December 26, 1867, at age 22. He had hazel eyes, brown hair, fair complexion and was five feet, nine inches tall. After Hickok wounded him, he remained in the Fort Hays post hospital until August 25. Five months later he was arrested and court-martialed for a drunken outburst which ended his career in the 7th Cavalry.

His trial began February 25, 1871. Several soldiers testified in the early morning hours of February 1 Lonergan appeared at the bunk of Corporal Zametzer and tried to arouse him from bed. He kicked at the bed several times and began to curse at Zametzer. Two soldiers escorted Lonergan to his bunk and told him to go to sleep. Lonergan was intoxicated, loud and boisterous. Corporal James Byrne said Lonergan threatened that “he would shit in the room [barracks] if he had a mind to and nobody would say a word to him.” Things calmed down until shortly before dawn when Lonergan got up, and according to bugler John Murphy, “instead of going to the rear he stopped and done his business in the quarters.” When asked what Murphy meant, he replied that Lonergan had “made a deposit of man manure on the floor.”

Upon learning this, Capt. Frederick W. Benteen ordered Lonergan arrested. First Sergeant Frederick Thies went to awaken Lonergan and escort him to the guardhouse. Thies was the same soldier who three years earlier arrested John Kile for a drunken escapade in New Mexico while in the 37th Infantry, and who after re-enlisting in the 7th Cavalry arrived at Hays on the same day Hickok had his deadly brawl. Thies reported:

Seeing that he wished to make resistance I put on my belt and pistol and then ordered him to follow me to the guardhouse immediately. Upon that the prisoner drew a clasp knife from his pocket, opened it, and said, “If you say another word to me I’ll cut the guts out of you,” I, knowing the disposition of the prisoner, then drew my pistol and thereby probably prevented actual violence on his part.

Lonergan called several soldiers in his defense, who stated he was only slightly intoxicated and denied he was boisterous and loud. The trial lasted four days. He was found guilty on all counts, sentenced to the Fort Leavenworth prison for the remainder of his enlistment—until December 26, 1872—forfeited all pay and given a dishonorable discharge.

Six months into his sentence Lonergan wrote to Secretary of War W. W. Belknap and pleaded for a second chance. He believed his trial was not fair because the officers were already prejudiced against him. He wrote:

I hereby ask for a remission of sentence and to be a gain restored to duty if such is possible having bin in the U S service since 61 and endured all the hard ships of a soldiers life during the late rebellion suffered the hard ships of Southern prison as a prisoner of war for 8 months upon being discharged I a gain joined the Regular Army and have served honorably ever since until the misfortune of being court-martialed befell me I have no disliken to become a soldier a gain having never deserted the Army I feell my self capable of doing the duty of a soldier in every respect.

Lonergan was denied clemency and disappeared from recorded history. If Ryan’s memoirs are correct, Lonergan was soon killed in another incident involving an infantryman. But there is an enticing different possibility needing further investigation. Records in 1903 from an old soldiers’ home has a log book noting:

“Jeremiah Lonergan b. abt 1838 Ireland entered Soldiers Home Bath, NY 1903; Co E, 12 NY Cav, Enlisted 09-21-1864, Troy, NY [two of Kile’s five enlistment papers said he was born in Troy, so if this is the same Lonergan this might be why they gravitated into friendship in 1870]; Discharged 06-19-1865, Halifax, NC.”

Could this be confirmation that Lonergan did serve in the Civil War as he reported in his appeal to stay in the service?

Jeff Broome is a sixth-generation Coloradan. He has published several books on the Indian war covering 1864-69. His newest book is Indian Raids and Massacres Essays on the Central Plains Indian War (Caxton Press, 2020). A retired philosophy professor, Jeff lives in Beulah, Colorado.