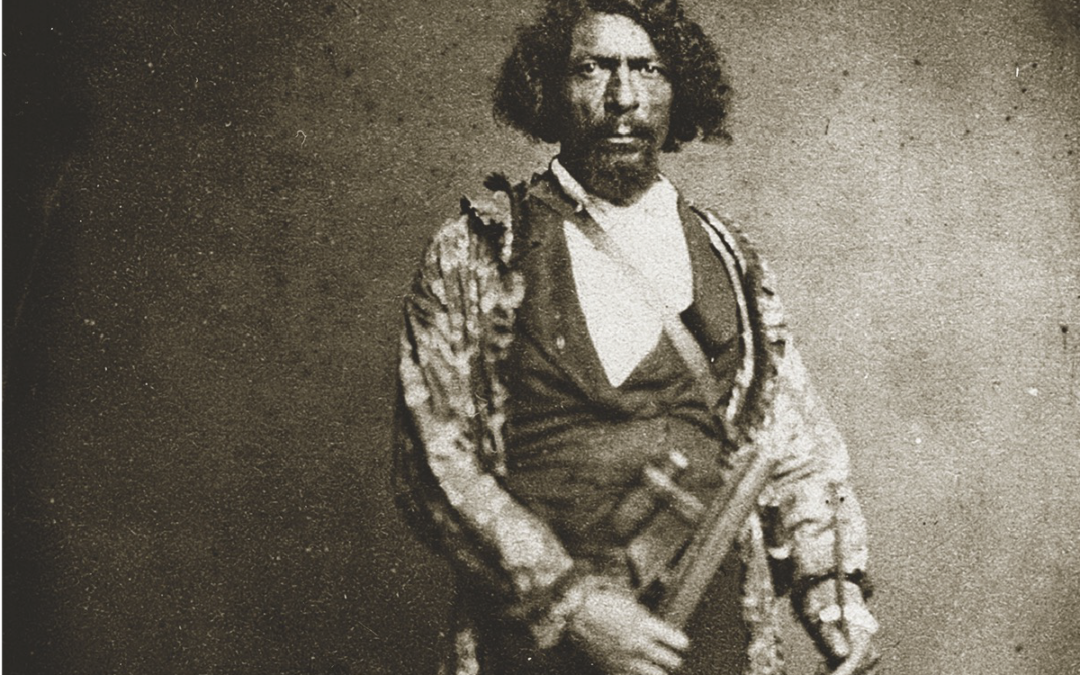

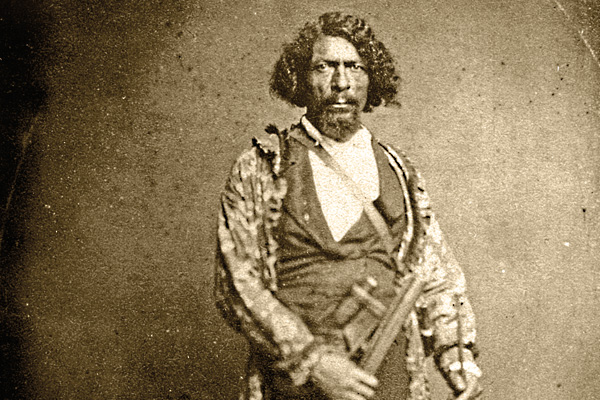

The legendary mountain man left a legacy of truth and fiction about his larger-than-life experiences as a trapper and trailblazer of the American West.

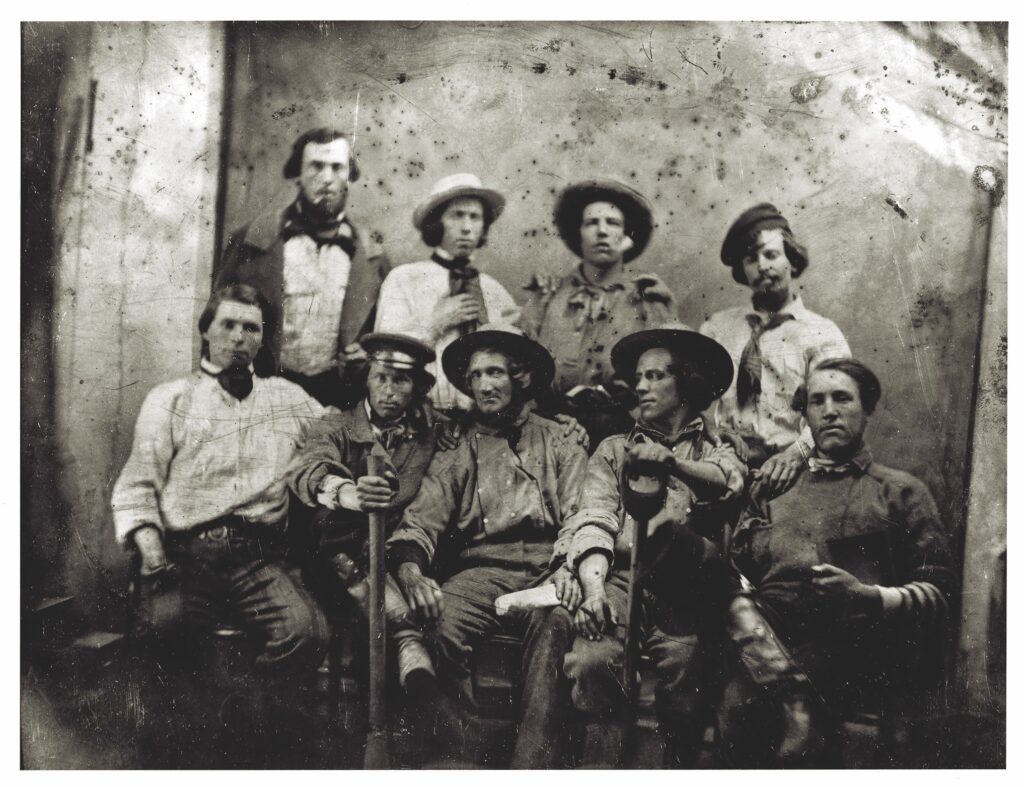

True West Archives

“We reached the American Valley without the least accident, and the emigrants expressed entire satisfaction with the route… A northern route had been discovered, and the city had received an impetus that would advance her beyond all her sisters on the Pacific shore. I felt proud of my achievement, and was foolish enough to promise myself a substantial recognition of my labors.” —Attributed to James Beckwourth by T.D. Bonner on the arrival of the first wagon train traveling via the Beckwourth trail in Marysville, California

The Man, the Myths, the Legends

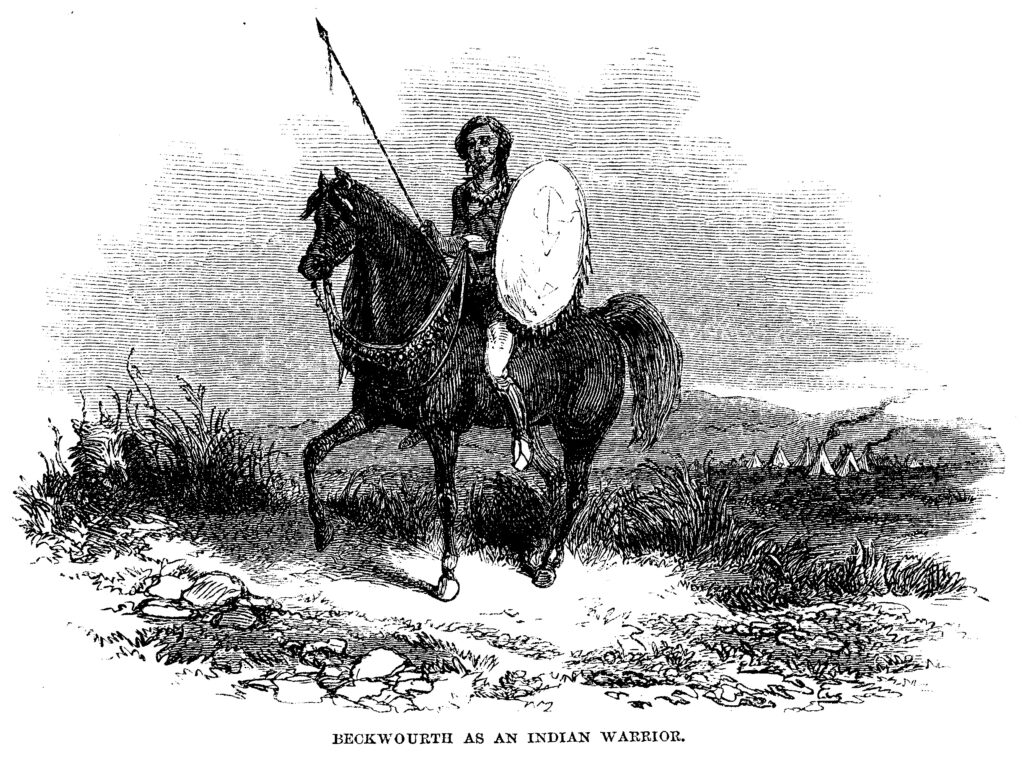

James Beckwith (changed to Beckwourth in 1853) earned a place in the pantheon of the Mountain Men who opened the West. Jim rode, trapped, hunted, traded and fought alongside many of those rugged individuals who became legends of the fur trade era. That was the first act of a career as a frontiersman that encompasses roughly 50 years. Jim traveled the nation, a witness to its growing pains. He was at many important events in American history, including the Bear Flag Rebellion, the Seminole War and Sand Creek Massacre. He was a war chief among the Crow Indians. His resume includes a variety of jobs—trapper, scout, hunter, wagon guide, hotel manager, dispatch rider, trader, merchant, horse thief, warrior, prospector and gambler to name a few. Beckwourth is remembered more for his racial heritage than the astounding life he reputedly led. Even with a stellar resume, equal or better than many of his contemporaries, Beckwourth did not always get the respect he had earned.

“Beckwourth, a mongrel of French, American and Negro blood…is a ruffian of the worst stamp, bloody and treacherous, without honor or honesty…” —Francis Parkman

Given the inconsistent record-keeping associated with the fur trade, Parkman’s damning of Beckwourth reads more as a fit of racial pique, rather than a cold reading of the historic record. Jim’s mixed-race background, his unabashed preference for living as an Indian, his multiple wives and his boastful pride in his own accomplishments did not set well with many Americans, especially in a world where people of color were not supposed to rise to the level of celebrity he achieved.

Beckwourth’s public championing of American Indian issues was not popular in his world. This is a curious aspect of his life. As a Crow war leader, Army scout, vigilante and militiaman, he had cause to fight the Lakota, Cheyenne and other tribes in numerous actions. Yet, he took up their cause, arguing for fair treatment at the hands of the government and White society. When Jim was called to testify at the Congressional hearing regarding the Sand Creek Massacre, the representatives of the military shut down his testimony regarding his conversations with the Indian prisoners and survivors of the massacre. The military argued that Beckwourth was being treasonous by trying to insert the views of an enemy into the proceedings.

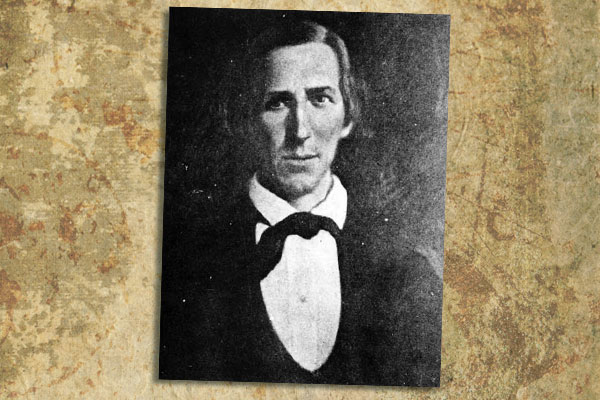

Beckwourth unabashedly liked to talk about himself to anyone who would listen. In the process he left an impressive number of stories about his adventures and misadventures. Jim was somewhat of an entertainer in social settings. Embellishment came as second nature to the storyteller. Jim did not see himself as a chronicler speaking to history. Some stories about him are true, while others are loosely based upon fact. Yet more recollections were made up by James, and more made up by others, including his chosen biographer T.D. Bonner. Bonner is credited with polishing up Beckwourth’s recollections and seems to have invented a few details in the process. Samuel Butler wrote, “Any fool can tell the truth, but it requires a man of some sense to know how to lie well.”

Fuzzy facts are common during this period. Many of Beckwourth’s contemporaries, such as Jim Bridger, were afflicted with the same penchant for spinning stories and enhancing their own legends without raising the ire of one of the nation’s foremost contemporary historians.

The result of all these wagging tongues and “polishing” of imperfect recollections is that, for a substantial portion of what we have heard about Beckwourth, it remains difficult to define precisely what might be factual. There are consistencies in the descriptions of those who met him as to his affability, bravery and fairness in trade that have a ring of authenticity. Jim’s poor memory for dates and spelling of place names complicates attempts to pin down his participation in several events. The date of his birth, the specifics of his mixed-race ancestry, his status among the Crow Indians, the spelling of his name, and even the cause of his death have unsettled aspects about them.

Beckwourth’s descriptions of life among the Crow people ring truer than his more self-serving descriptions of combat and survival. As with many of his contemporaries, we consume their recollections with a grain of salt. Perhaps in our search for the unattainable truths of the man’s story we have lost the meaning of his rise from humble beginnings to succeed and survive in worlds where the odds in opposition to both were stacked against him. It is sufficient to say that Beckwourth was very active in the fur trade era and the subsequent opening of the West. Few of his contemporaries covered as much territory and were present at as many of the events that made up the complex history of Westward expansion.

Ho to California!

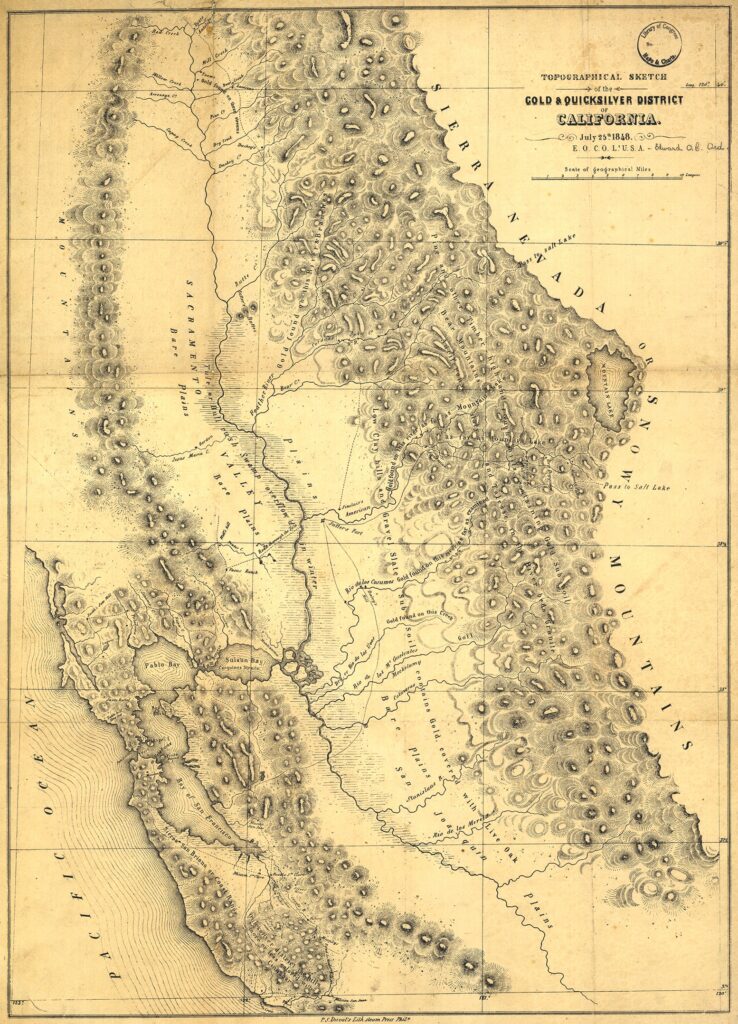

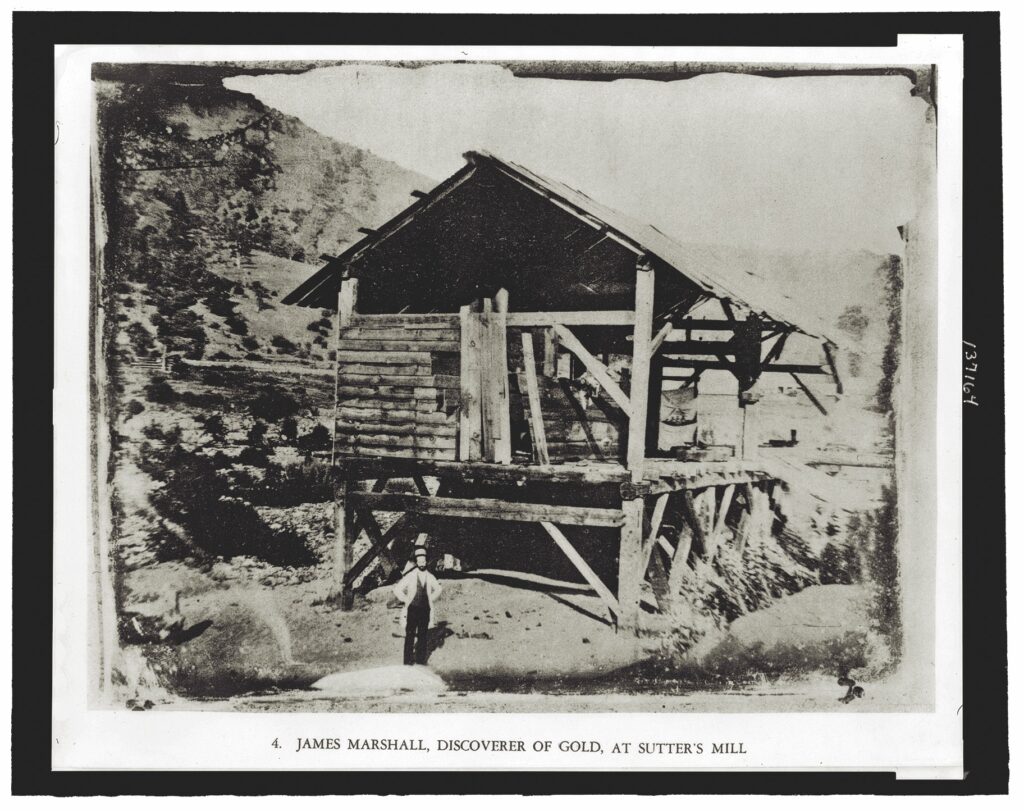

The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill on the American Fork River set in motion an international exodus that Jim was well-positioned to exploit. In 1849 Jim had been working as a dispatch rider and livestock trader. His income was supplemented by his work as a monte dealer. For a brief time, Jim was fabulously rich from his winnings. All too soon the money was spent and he moved on to the Greenwood Valley where he was laid low for the winter by rheumatism.

As his health improved, he took the path of many Californians who abandoned their previous lines of work for the lure of easy riches in El Dorado. In the spring of 1850, Jim tried his hand at prospecting. It was during these explorations he noticed a low pass (5,221 feet above mean sea level) which appeared to traverse the Sierra Nevada. Recognizing an opportunity, Jim returned from his unsuccessful attempt at striking it rich and explored the pass. He determined the route was suitable for wagons and provided good grass and water with gentler terrain within the pass than the tried-and-true wagon routes. The hard lessons of the star-crossed Donner Party of 1846-47 were a vivid memory in California, and the Truckee route through, what later became Donner Pass—altitude 7,057 feet above mean sea level—leading to Johnson’s Ranch became all but impassible during the snowy months. Those unfortunate emigrants resorted to murder and cannibalism to survive. The harrowing tales of the survivors became infamous and even cast a pall on the route, despite the lure of quick riches once over the Sierra.

Courtesy Library of Congress

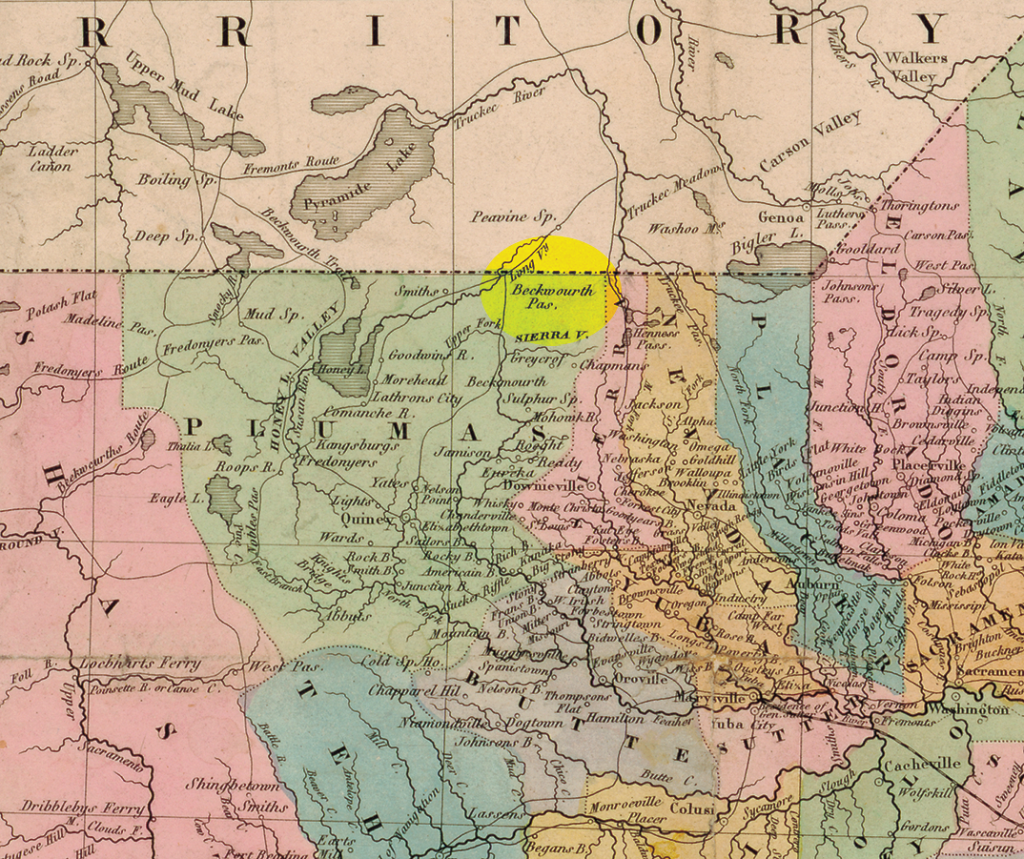

Beckwourth’s pass, at almost a third of a mile lower elevation than Donner Pass, was expected to remain snow-free longer and have less snowpack to contend with over the course of a season. Jim recognized his pass, positioned to the north of the Truckee route, had the potential to become the most popular route. He set about developing a trail through the pass with his own financial resources. According to Beckwourth, Marysville, which already served as a support hub to many of the northern mines, agreed to help support the road. A wagon road linking the community to the east, and allowing emigrants direct access, was a desirable development.

Beckwourth set about carefully laying out the new wagon road. The route departed from the Truckee Route in the Glendale Valley near the modern location of Sparks, Nevada, and took a northerly route, swapping length of travel for challenges created by slope. The winding trail went through the relatively gentle pass discovered by Jim and bent a large arc to the north. The destination of the Beckwourth trail was Bidwell Bar Ranch, where a wagon road entered from the east and an improved road headed north to Marysville from there. In all, Jim’s winding route traversed roughly 200 miles.

Like most new wagon routes of the period, Beckwourth’s trail was advertised with a certain amount of exaggeration. Jim claimed it as “the best wagon-road.” Others promoted its abundance of good grass and water, both necessary for keeping livestock healthy. The pass was compared with South Pass in modern Wyoming for presenting a gradual slope. The easy nature of the pass is indisputable. However, the pass is but a small part of a long route. There are roughly 150 miles of more challenging travel beyond the western end of the pass. Emigrants lulled by the inviting nature of the pass soon found that rocky trail and crossings of five mount-ains were ahead. The difficulties in terrain reached an apex in ascending the mountain near Beckwourth’s War Horse Ranch, where his hotel and trading post were situated. Traveling the route in 1852, John Denton described the mountain as being “…a mountain that is a mountain…” and rocky with a slope approaching that of the roof of a house. All of these difficulties paled in comparison to Donner Pass. Colossal snowdrifts, frequent in Donner Pass, were able to bring livestock-powered travel to a halt in ways that slope and rocky terrain rarely matched.

Guide, Rancher, Publican and Mercantilist

In 1851, Jim guided the first wagon train through the pass and into the Marysville area.

A member of that wagon company was 11-year-old Ina Coolbrith, destined to become the poet laureate of California. The little girl was smitten with their charismatic guide. He was tall, swarthy, hair braided in Crow style, and every bit the walking, talking epitome of the heroic Rocky Mountain men who opened the West. She recounts the joy of being allowed with her sister to cross the pass riding bareback on one of Jim’s horses. “Here is California, little girls, here is your kingdom,” she remembers him announcing. In an unfortunate twist of fate, the town burned to the ground. Was it a celebratory accident or arson? As luck would have it for James, the burning of Marysville was credited to him in gossip, despite the fact that he depended on the good graces of the community of Marysville to help him recover the costs of preparing the trail.

On September 1, 1851, Beckwith & Company submitted a petition to the Marysville Town Council in an attempt to receive remuneration for the expenses incurred preparing the wagon road. The document was referred to a committee and was never acted upon. The money supposedly promised by Marysville did not materialize, and Jim decided to make the best of things. He filed a land claim in 1852 and built a hotel and store at his Sierra Valley (soon to be Beckwourth Valley) ranch. He was not alone in establishing these lodging and mercantiles to serve the emigrant traffic. His War Horse Ranch became a hub of commercial activity. The most reliable gold in California was in mining the miners, and Beckwourth was an able salesman. Jim was able to build a frame house, the first seen by many emigrants in months of travel. Jim entertained his customers by recounting episodes, both real and imagined, from his adventurous life. The next year Jim was busy in a small cabin recounting his memoirs to T.D. Bonner.

By 1853 Beckwourth’s trail proved to be a success. It is difficult to determine accurate numbers of emigrants who used the new route, but by some accounts it was the most popular route for a short time. Use of Beckwourth Trail continued into the 1860s, but traffic numbers declined once tolls were levied for its use. By 1855 trader Beckwourth left his wagon road, moved to Colorado and opened a general store. There were adventures sufficient between 1855 and his death in 1867 (or 1866) to fill most lifetimes. He fought against the Apaches and the Cheyennes as a militia member. He was a scout for the military at the Sand Creek Massacre (November 29, 1864) and was either poisoned or died of natural causes when guiding the military to a Crow village in Montana. Say what you will about James P. Beckwourth, his was not a boring life.

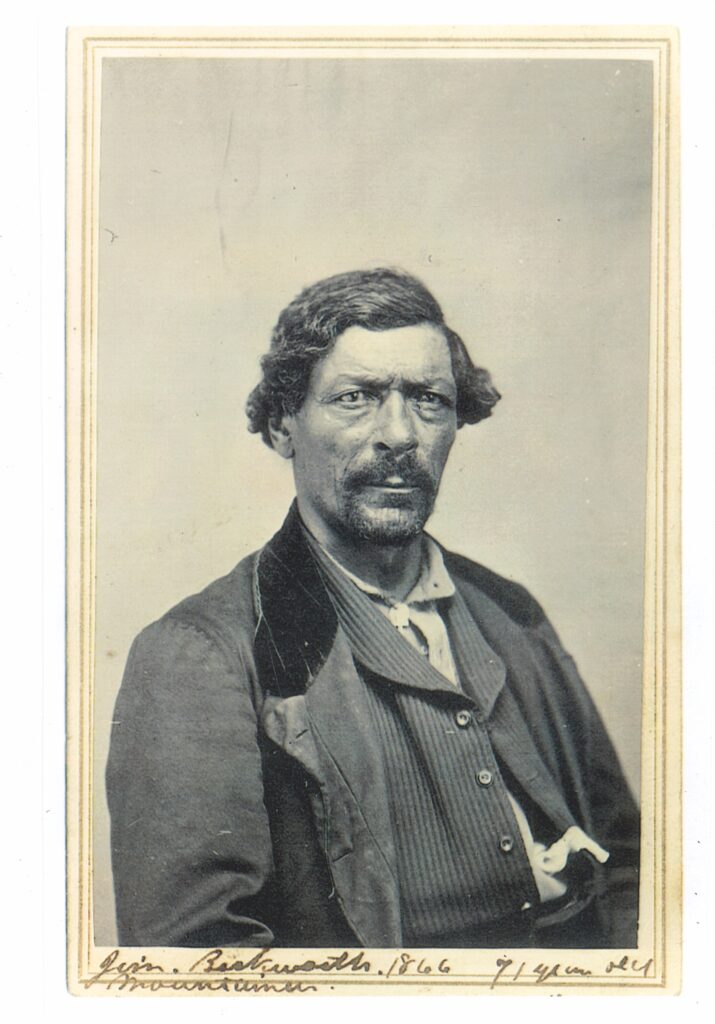

True West Archives

Terry A. Del Bene the author of The Donner Party Cookbook: A Guide to Survival on the Hastings Cutoff and several other historic books about the American West.