Following David Crockett to the Alamo is a heritage trip of a lifetime.

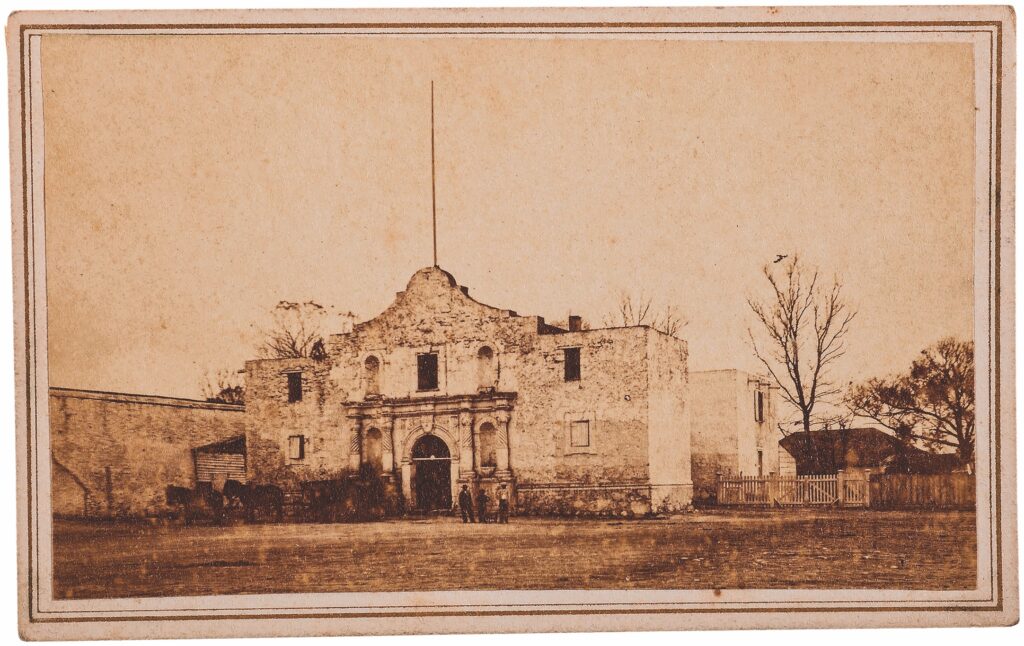

Alamo Photo by Carol M. Highsmith Archives Courtesy Library of Congress/Historic Alamo Image Courtesy True West Archives

In 1835, David Crockett was a noted author who had spent much of the previous year promoting A Narrative of the Life of David Crockett of the State of Tennessee (written with Thomas Chilton). Now, he had two new books out. He also had a wife (sort of), a family (when he saw them) and the status of living legend.

What he didn’t have was a job.

By only 252 votes, the citizens of Tennessee’s 12th Congressional district had chosen Adam R. “Old Black Hawk” Huntsman, who had lost a leg in the 1813 Creek War, to represent them instead of Crockett. Crockett took defeat as graciously as one might expect from a man of the cane, writing his publishers that “I was Completely Raskeled out of my election.”

That fall, Crockett set off for Texas with nephew William Patton and neighbors Lindsy K. Tinkle and Abner Burgin.

Early Years

Crockett was born on August 17, 1786, near Limestone, Tennessee (David Crockett Birthplace State Park). In 1794, the Crocketts moved to what is now Morristown (Crockett Tavern Museum). Married to Polly Finley in 1806, Crockett resettled his family in Lincoln County in 1811, then Franklin County, served in the 1813 Creek War and moved to Lawrence County in 1817, becoming a justice of the peace and Lawrenceburg’s town commissioner. Polly died in 1815, and Crockett married Elizabeth Patton the following year.

Though preferring wandering and hunting, Crockett was elected to the state legislature in 1821, lost an 1825 bid for a U.S. Congressional seat but won it two years later. He was an Andy Jackson man, till Jackson decided to kick American Indians out of their Southeastern homelands. Crockett railed against Old Hickory—another reason Crockett lost that 1835 election.

All Images by Johnny D. Boggs Unless Otherwise Noted

Leaving Tennessee

Sam Houston, who had also bumped heads with Jackson and left politics after a matrimonial scandal, had returned to Tennessee after spending time in the Indian territories and Texas. Houston likely talked up Texas, so Crockett set out West, writing his brother-in-law that “we will go through Arkinsaw and I want to explore Texas well before I return.”

On November 10, Crockett and his crew reached Memphis (Davies Manor Historic Site, Sun Studio). He enjoyed “horns of drink with citizens and comrades at the Union Hotel, Hart’s Saloon, and Neil McCool’s establishment,” Michael Wallis writes in David Crockett: The Lion of the West. And it was here, Wallis writes, that Crockett gave his famous quote:

“Since you have chosen to elect a man with a timber toe to succeed me, you may all go to hell and I will go to Texas.”

The Truth Teller, a Jackson, Tennessee, newspaper, reported that Crockett was “going to join the American forces against the Mexicans.” The Vermont Gazette was blunter, reporting that Crockett “modestly gives out that he will have Santa Anna’s head for a watch-seal before the campaign is over.”

Arkansas traveler

Crockett and his pards were ferried across the Mississippi River into Arkansas. On November 12, the party reached Little Rock (Historic Arkansas Museum, Old State House Museum), where Crockett took in a puppet show and butchered a deer behind the Jeffries hotel.

The Gazette reported that news of the arrival of Crockett—“the reel critter himself”—“rapidly spread, and we believe within bounds, when we say, that hundreds flocked to see the wonderful man, who, it is said, can whip his weight in wild-cats, or grin the largest panther out of a tree.”

Anti-Jackson men treated Crockett to supper.

“We shall die contented,” the editors of The Advocate said. “We have seen the Hon. DAVID CROCKETT—who arrived in this place this evening, on his way to Texas, where he contemplates ending his days.”

The journalists did not know how prophetic they were.

By then, newspaper reports numbered the party at six to eight. Crockett’s entourage moved on to Washington (Historic Washington State Park) for another evening of food, drink and tall tales. But where Crockett went next is debated.

He could have crossed in present-day Sevier County, Arkansas, or traveled the military road to Fort Towson (Fort Towson Historic Site) in present-day Oklahoma. Or stepped into Texas somewhere else.

Gone to Texas

Wherever Crockett entered Texas, he made it to Santa Fe Trail magnate William Becknell’s homestead near Clarksville (Red River County Jail Museum). He got as far west as Honey Grove and disappeared for so long, reports of his death appeared in Eastern newspapers. But in January, Crockett and pals arrived in Nacogdoches (Millard’s Crossing Historic Village, Stone Fort Museum).

How he got there depends on who tells the story. Some say he returned to Arkansas, boarded a steamboat on the Red River at Fulton, and floated to Natchitoches, Louisiana (Fort St. Jean Baptiste State Historic Site)—perhaps for great blackened alligator—and then rode east to Natchitoches’s sister city. Or maybe he merely cut across Texas to the state’s oldest town.

There, he gave a rousing speech and he and his compatriots pledged their allegiance to Texas’s provisional government. From Natchitoches, Crockett traveled to San Augustine (Mission Dolores State Historic Site), where he wrote a letter to his daughter, Margaret, and her husband in Gibson County, Tennessee, saying “do not be uneasy about me for I am with friends.”

Crockett and the Tennessee Mounted Volunteers set out to join the fight, reaching present-day Washington (Washington-on-the-Brazos State Historic Site) and eventually San Antonio (Briscoe Western Art Museum), where he entered the Alamo.

That’s where David Crockett’s life ended, but not his legend. William M. Groneman III, author of David Crockett: Hero of the Common Man, tells me there’s a good reason to remember Crockett today:

“The real Davy Crockett occupies a unique position as a distinctly American character. He came into prominence as the founding fathers with European ties were passing from the scene. His life stands on a foundation of hard work, generosity, decency, public service and bravery.

“The editor of The Niles Register, when asked to describe Crockett reported, ‘Just such a one as you would desire to meet with if any accident or misfortune had happened to you on the highway.’

“Today, details of his life are stretched thin to cover the demands of American history, revisionist history, folklore and popular culture.”

A Wide Spot in the Road

TEXAS RANGER HALL OF FAME AND MUSEUM

In 1823, the absence of an army to protect American settlers in the Mexican province of Tejas led empresario Stephen F. Austin to organize a group of men to “range” over the country. The Texas Rangers were born—as a military or quasi-military unit, though; they wouldn’t become a law-enforcement agency until 1874. The Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum had its beginnings in 1968, when the Homer Garrison Texas Ranger Museum opened at Fort Fisher Park in Waco. Today, the Hall of Fame honors 31 Texas Rangers—like John S. “Rip” Ford, who made significant contributions to the organization; and Stanley Keith Guffey, killed in the line of duty while protecting a two-year-old kidnapping victim in 1987. The museum includes a treasure trove of Rangers memorabilia, from badges and firearms to movie posters and lunch boxes. The Tobin and Anne Armstrong Texas Ranger Research Center, which opened in 1976, houses photographs, correspondence, service records and case files. TexasRanger.org

Good Eats & Sleeps

Good Grub: Loveless Café, Nashville, TN; Central BBQ, Memphis, TN; Pig and Whistle Café, Honey Grove, TX; Trail Boss Steakhouse, Natchitoches, LA;

Casa Rio, San Antonio, TX

Good Lodging: Urban Cowboy, Nashville, TN; Capital Hotel, Little Rock, AR; The Courthouse Inn Bed and Breakfast, Clarksville, TX; Crockett Hotel, San Antonio, TX

Johnny D. Boggs recommends David Crockett: The Lion of the West by Michael Wallis—and anything Wallis has written.