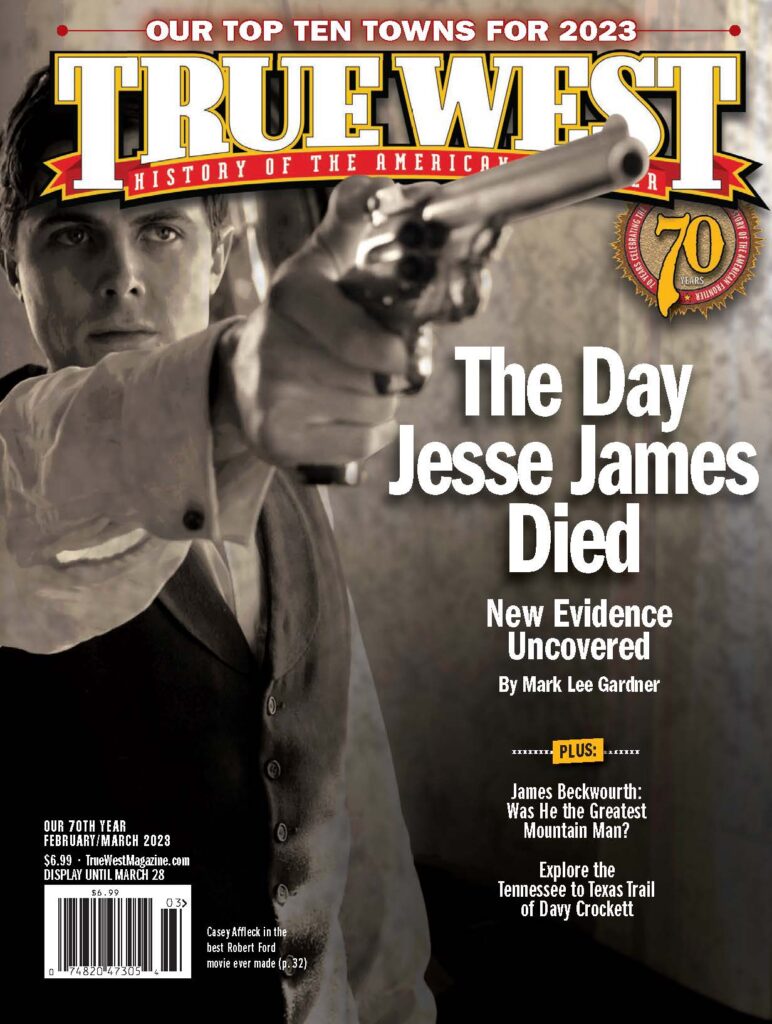

For over 140 years, Bob Ford’s cowardly killing of Jesse James has fascinated historians seeking the truth behind the assassination.

“That man is Jesse James and we have killed him and don’t deny it. We feel proud that we have killed a man who is known all over the world as the most notorious desperado that has ever lived.” —Bob and Charley Ford

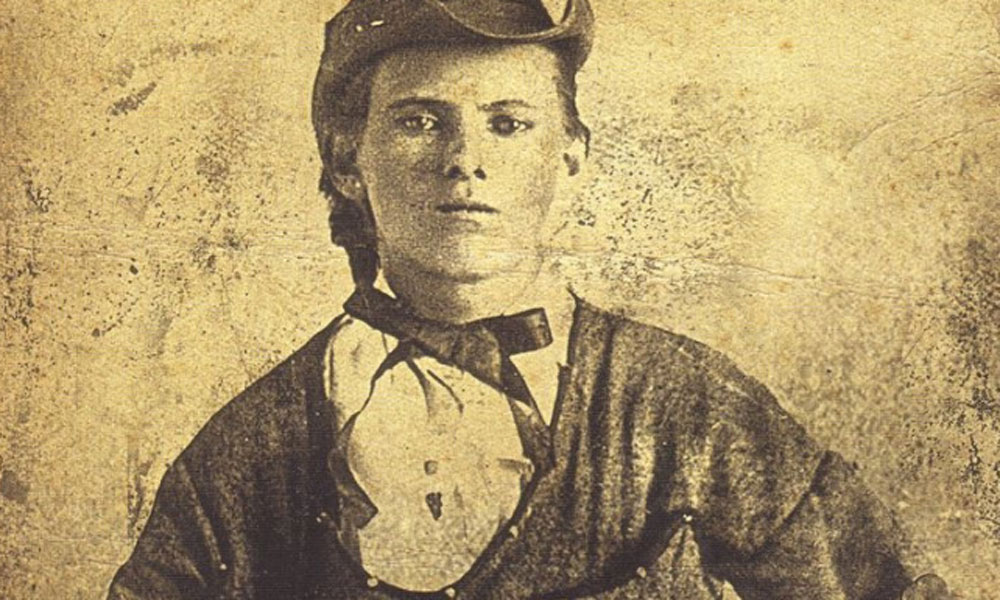

Five months short of his 35th birthday, Jesse James had much on his mind. Money was tight. In fact, he was nearly broke. He had a wife and two children to support, and he knew they couldn’t stay in their small, rented cottage on that high hill in St. Joseph, Missouri, forever. There was a farm in southern Nebraska he was keen on buying, and he’d written the man who’d advertised it in the newspaper, but the purchase would require cash on the barrelhead.

At the same time, Jesse James was itching for some action, for a return to the exhilarating days when he, Frank and the Younger brothers had relieved banks and trains of crisp greenbacks and double eagles. It’d been a long time since the notorious outlaw had made headlines, and no one reveled more in making headlines than Jesse. But he was about to fix that, or so he told Bob and Charley Ford, his “gang” at present.

Jesse’s sights were set on the bank at Platte City, a county seat 30 miles south of St. Joseph. The murder trial of George E. Burgess, accused of killing his cousin, had begun that very day, April 3, 1882. Jesse told the Fords they would leave that night for Platte City and hit the bank the next morning, while court was in session. “It would be a fine scheme and would be published all over the United States as a daring robbery,” Jesse boasted.

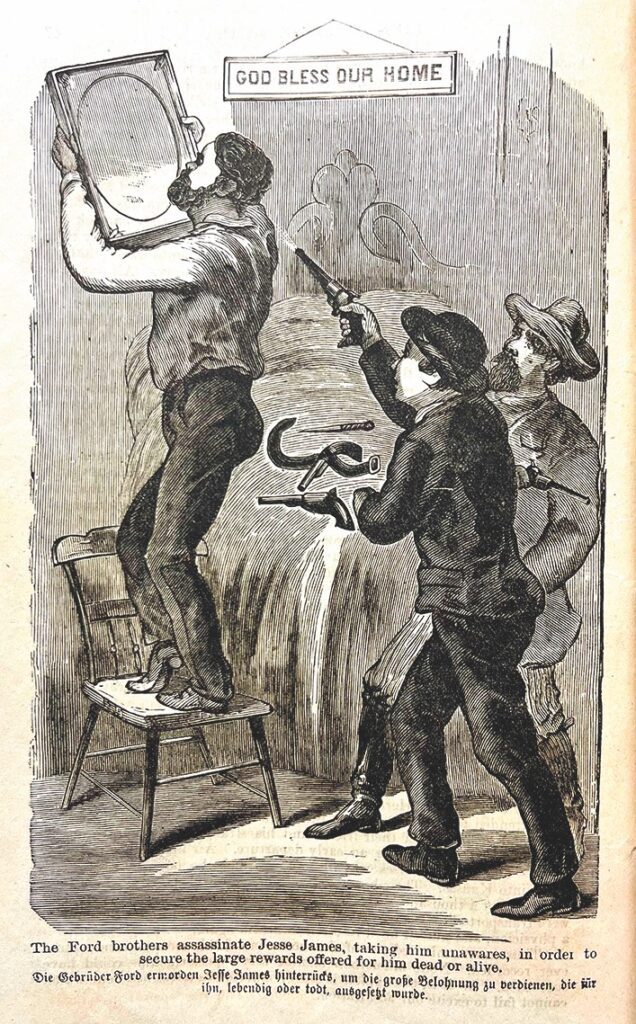

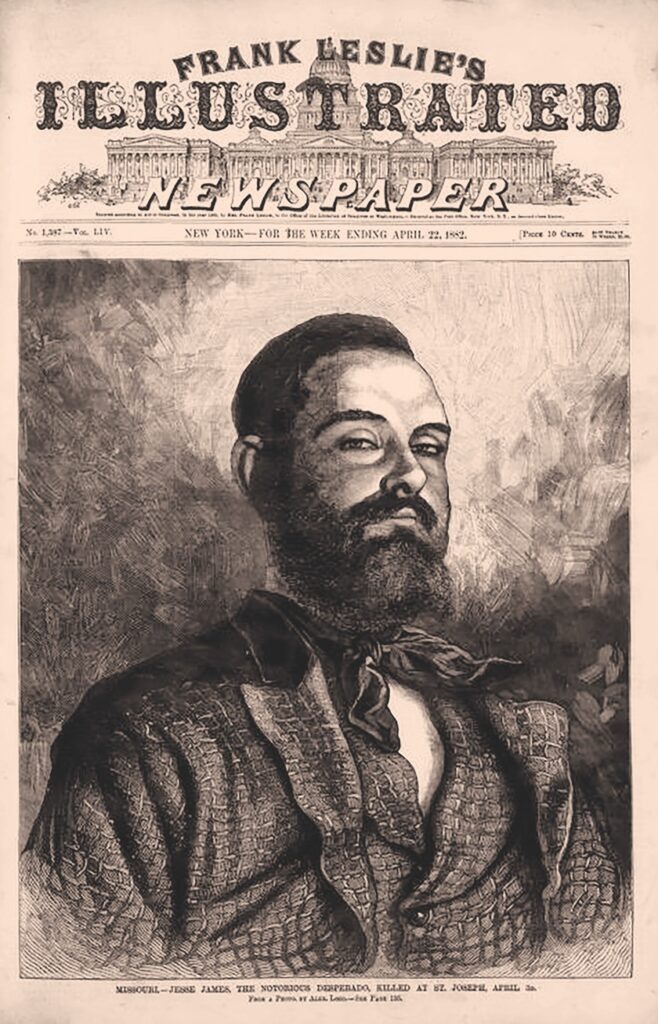

For the Week Ending April 22, 1882 Cover of “Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper”

Courtesy Internet Archive

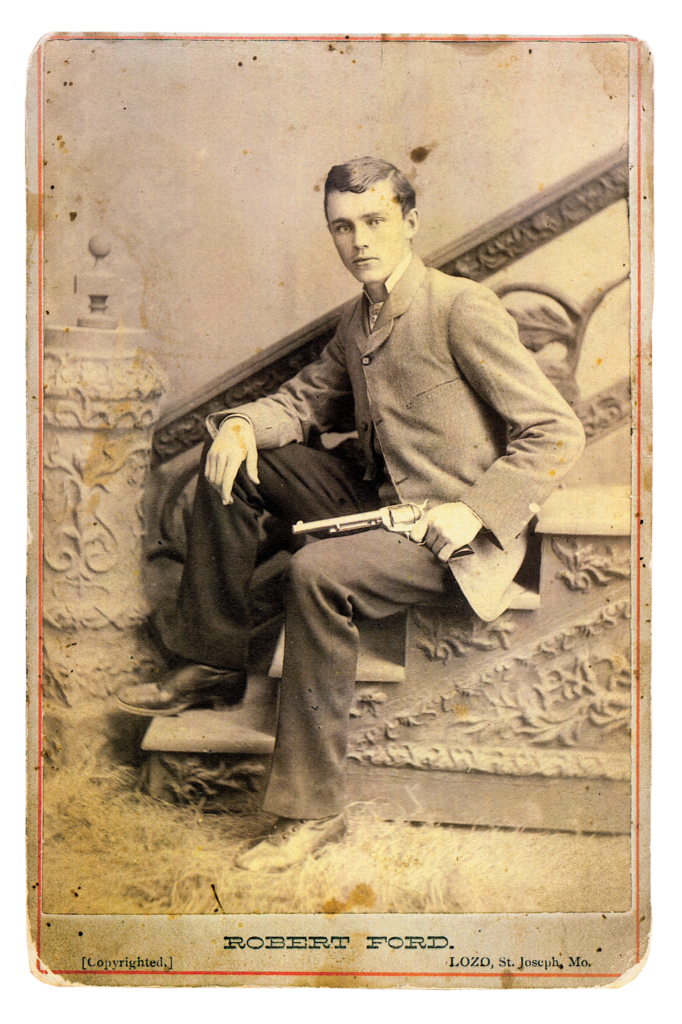

Bob and Charley Ford, 20 and 24 respectively, weren’t the Youngers—not even close. And whether or not they had any real grit remained to be seen, but they could pull a trigger, and Jesse believed they were loyal or “true.” He’d actually given the baby-faced Bob a handsome nickel-plated Colt .45 revolver. Even so, Jesse kept a close eye on the brothers and didn’t allow them to get too far away. Of course, Jesse watched everybody, Charley recalled, “even his own brother.” Having a $10,000 reward offered for one’s capture and conviction will do that to a man.

That Monday morning was too warm for Jesse’s liking, and he said so. Bob and Charley then watched as Jesse took off his coat and boots and tossed them by a chair, leaving plainly visible the gun belt he wore and the two revolvers he always carried. Jesse next stepped up to a bureau and combed his hair in front of the mirror. Seeing his guns in the reflection, he told the boys he guessed he better take them off, as the front door was open, and folks passing by could easily see inside. In an instant, then, Jesse removed his belt and weapons and threw them on the room’s only bed.

Despite all that was racing through the outlaw’s mind that day, he suddenly became fixated on something quite inconsequential. Hanging high up on the room’s east wall was a framed cabinet-sized portrait of his wife’s niece, Nannie Mimms. Jesse looked up at the picture and remarked that Miss Mimms needed dusting. He picked up a feather duster and while cleaning the picture accidentally knocked it askew. With “an exclamation of pettishness,” Jesse slid a chair under the portrait, stepped up on the chair, and grabbed hold of the picture.

As Jesse carefully slid the frame’s wire hanger to center, he heard a shuffling of feet and a slight creaking of the wood floor behind him, quickly followed by the sound of rapid metallic clicks, a sound as familiar to the gunman as his mother’s voice. Jesse started to turn his head….

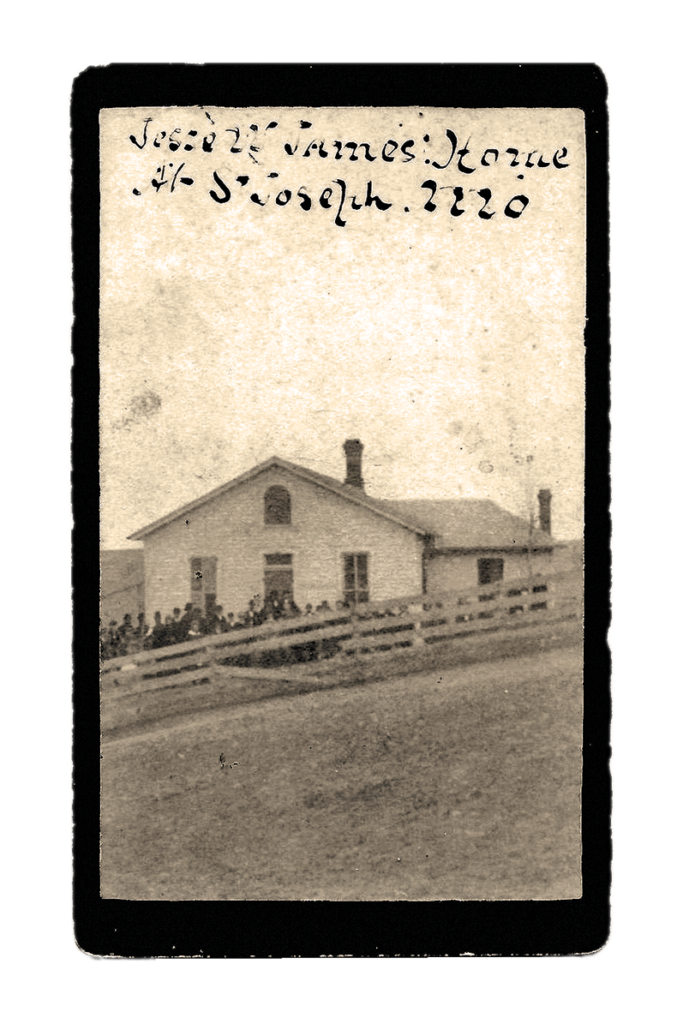

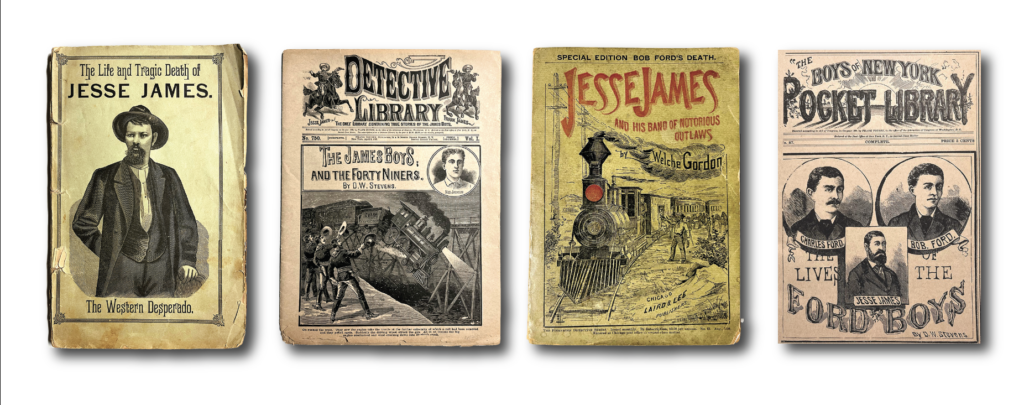

Selling the Legend

Today, the Jesse James “death house” sits on a small lot next to the Patee House Museum, just two blocks from its original location. Every day except Sunday, the story of Jesse’s murder is told and retold (through a recorded monologue) to anyone who has the four-dollar price of admission, a ritual that began almost immediately following Jesse’s death. Back then, the white cottage’s divorced owner, Mrs. Henrietta Saltzman, and her two young children served as the home’s first tour guides, charging the curious two bits to see where the notorious outlaw met his fate. Bloodstained wood splinters from the floor—no bigger than a toothpick—were available for another 25 cents.

By June of 1883, 4,000 paying customers had visited the outlaw’s last home, including railroad magnate Jay Gould, who was surely ecstatic that Jesse and his gang would no longer be interrupting train travel. Gould bought one of the wood splinters, supposedly to have it incorporated into a watch fob. What better accessory for the robber baron who has everything than the dried blood of a fellow scoundrel?

Despite the closeness of the iconic event, though, misinformation about the assassination was already pushing aside the facts. The Saltzmans, for example, gladly pointed to a ragged hole in the front room’s wall as the place where Bob Ford’s fatal round passed after punching through Jesse’s head. Indeed, Jesse’s assassin himself had appeared at the house’s door on May 29, 1882, and paid the quarter admission so as to settle a dispute “regarding the exact locality of the bullet hole in the wall”—at least according to Mrs. Saltzman. (Much to Henrietta’s chagrin, above Bob’s name in the house register someone had drawn a coffin featuring a skull and crossbones on the lid, together with the words “Death you deserve.” On the same line as Ford’s signature, another incensed visitor had scrawled “Coward.”)

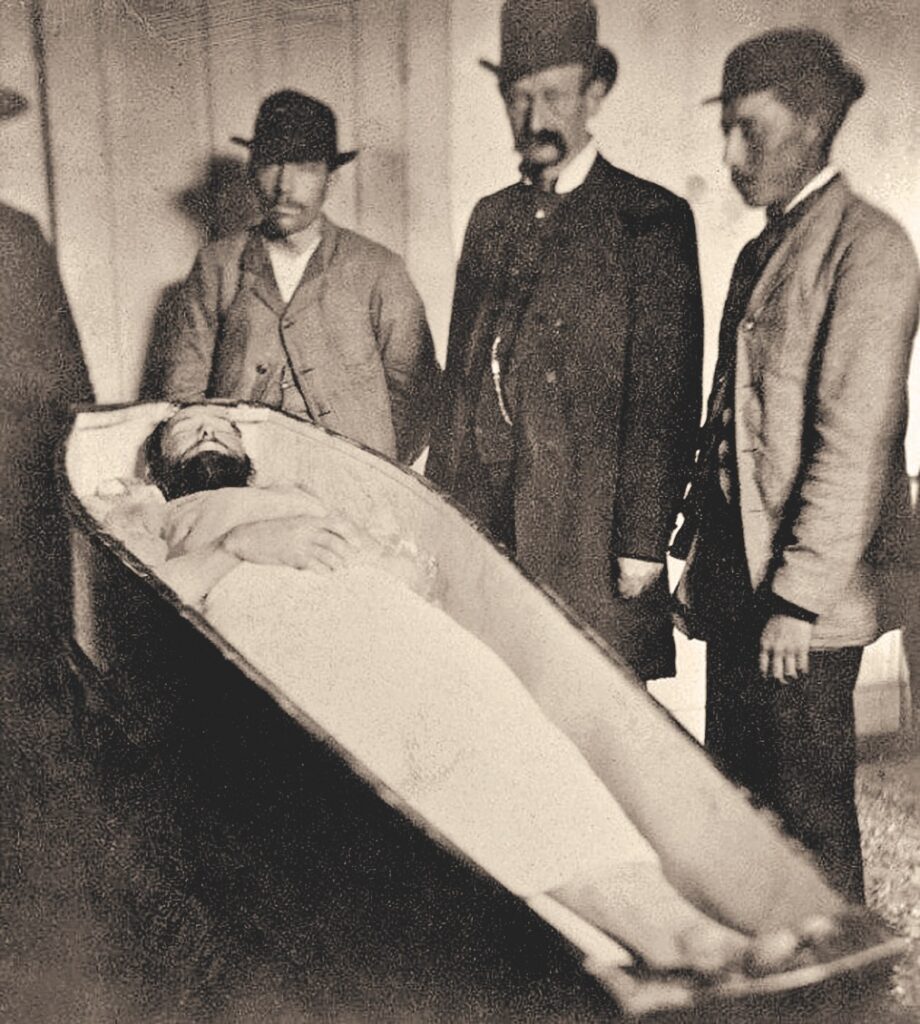

And yet, the results of an autopsy performed on the dead outlaw, prominently published in the St. Joseph’s Western News on April 6, 1882, revealed that the projectile had never left the outlaw’s skull. The doctors discovered it “under the cranium behind the left ear.” It was flattened out, the newspaper reported, and tiny splinters of bone were embedded in the lead. This finding was confirmed 113 years later when Jesse’s remains were exhumed and studied by forensic scientist James E. Starrs, who found no exit hole on the outlaw’s skull.

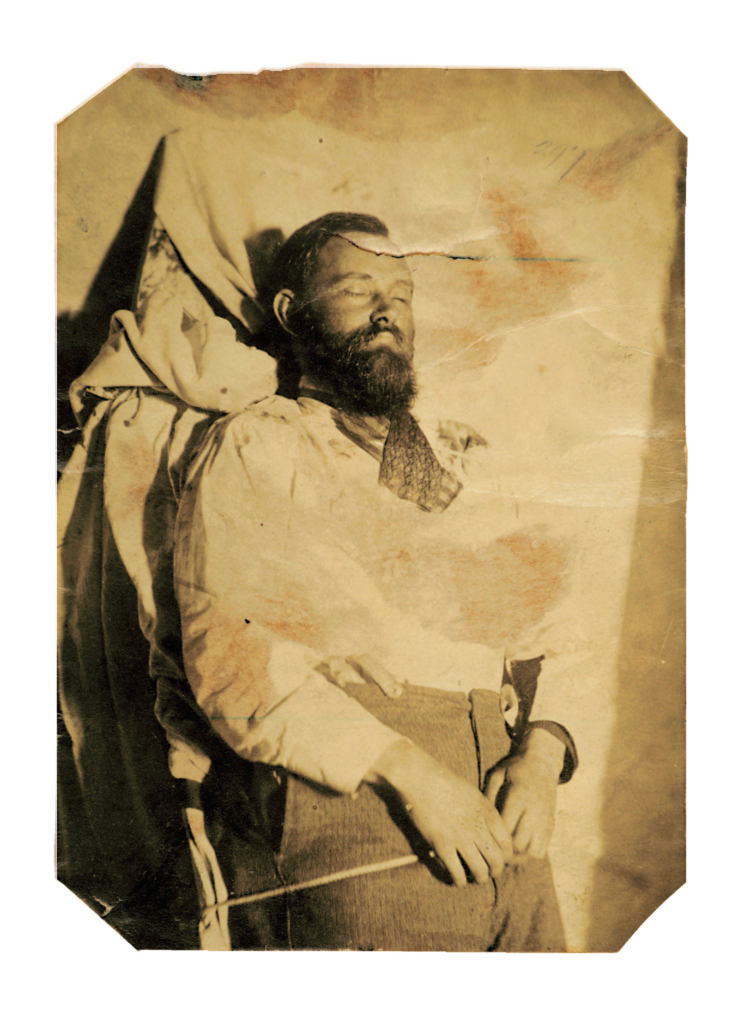

But what about that “ghastly wound” above Jesse’s left eye, the one that many observers believed to be an exit hole? The gash is plainly visible near the left eyebrow in at least one of the photos taken of Jesse’s corpse. The answer again comes from the autopsy: the cut was caused either by the outlaw’s head striking the chair or it came from the butt of a revolver. Did one of the Fords strike the prostrate outlaw to make sure Bob’s shot had done its work? When asked this question at the coroner’s inquest, Charley replied, “No, sir; nothing but the one shot.”

Images Courtesy True West Archives

A Tornado of Lead!

Tornado of Lead By Bob Boze Bell

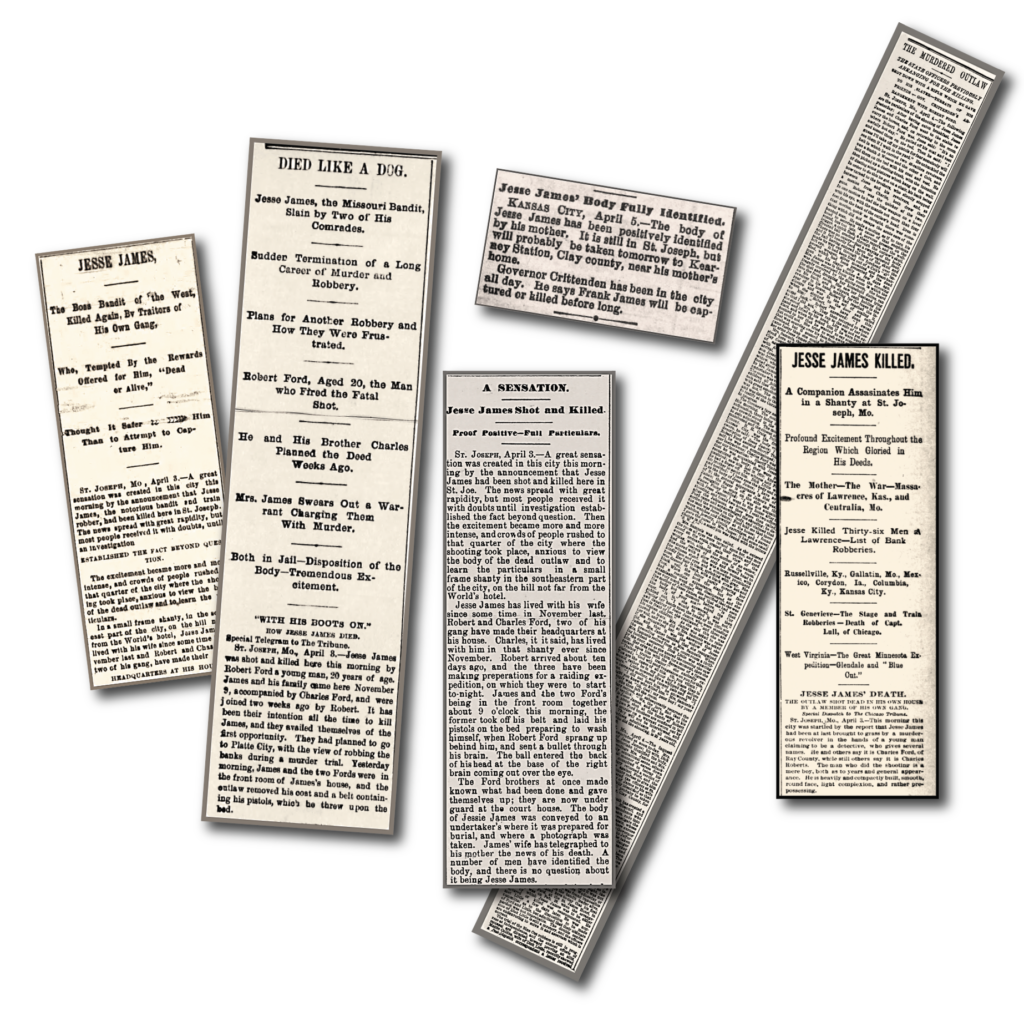

The killing of Jesse James produced a mountain of hot lead type from one end of the country to the other. Here are just a few of the screaming headlines from across the United State as the press went into a feeding frenzy.

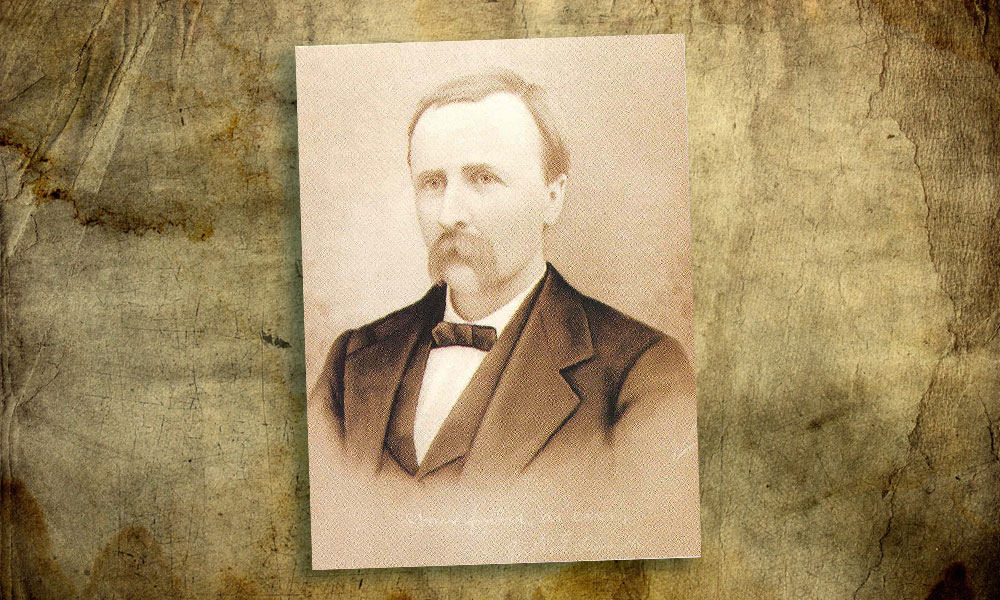

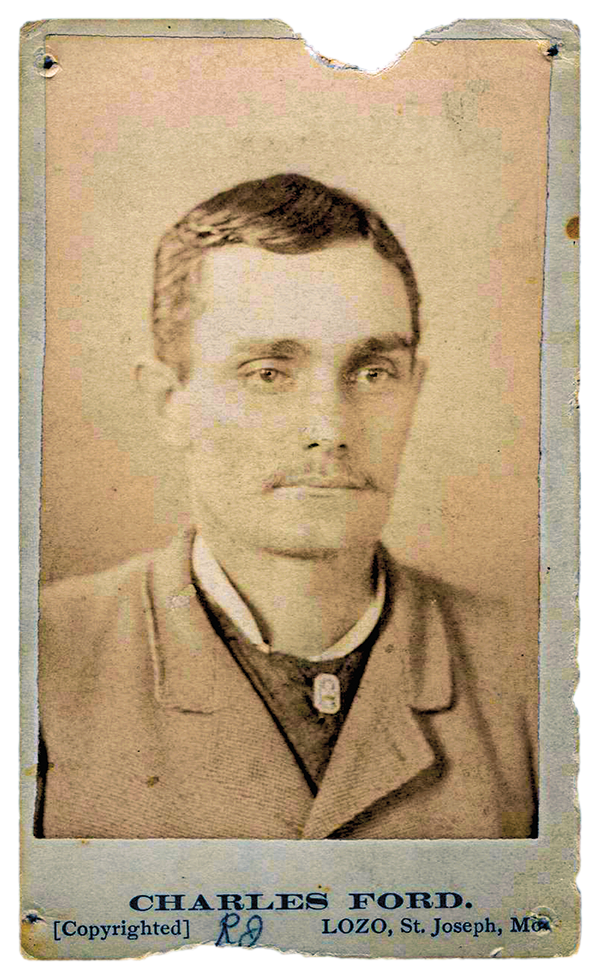

The Brothers Ford

The questioning had only just begun for Bob and Charley. When the pair later traveled to various cities reenacting their chilling deed in a play titled The Outlaw Brothers, they were obliged to tell their stories to local reporters once again. Several interviews, beginning on the day of the assassination, offer incredible firsthand information about the outlaw captain’s death, but it’s surprising how often what the Fords related has been overlooked or forgotten. The identification of the picture Jesse was straightening; the actual deal offered by Missouri’s governor ($40,000 for Jesse’s capture, $10,000 for the outlaw dead); the Fords’ confession that they’d never considered taking Jesse alive; the gun Bob used to kill Jesse (see sidebar p. 30)—these and other fascinating revelations the brothers freely offered, albeit at times contradicting themselves.

And in a weird sort of irony, the world obtained its first real insights into the flesh-and-blood Jesse Woodson James through the words of his killers. The brothers said “Jess” was a strong man with reflexes as quick as lightning. “He was so powerful,” Charley said, “that he could throw me about just like I could a baby a week old.” Jesse was also “the most interesting and entertaining man” they’d ever met, a sentiment shared by those in St. Joseph who’d gotten to know the outlaw as Mr. Thomas Howard.

The Fords told of how Jesse enjoyed recounting his numerous blood and thunder exploits (who else was he going to tell?), that he believed that God, whom the outlaw referred to as “The Master,” had seen him through so many close calls that he felt he was somehow protected. Consequently, they said, Jesse saw no reason to make a career change.

The Superstitious Family Man

It’s because of the Fords that we also know that Jesse was a strangely superstitious man. They claimed that Jesse wouldn’t start on a raid unless he’d seen the new moon clear. “He wouldn’t look at it through a window or a tree,” Charley recalled. “He wanted to see it clear.” Three days before Bob sent Jesse to meet The Master, Jesse saw the new moon “all clear and nice,” and he was thrilled. Charley couldn’t stand it any longer and asked his boss why in hell he believed in such nonsense. “By God,” Jesse blurted, “I suppose a man has a right to his opinions; I always have good luck if I can see the moon clear.” Turns out Charley was right about the nonsense.

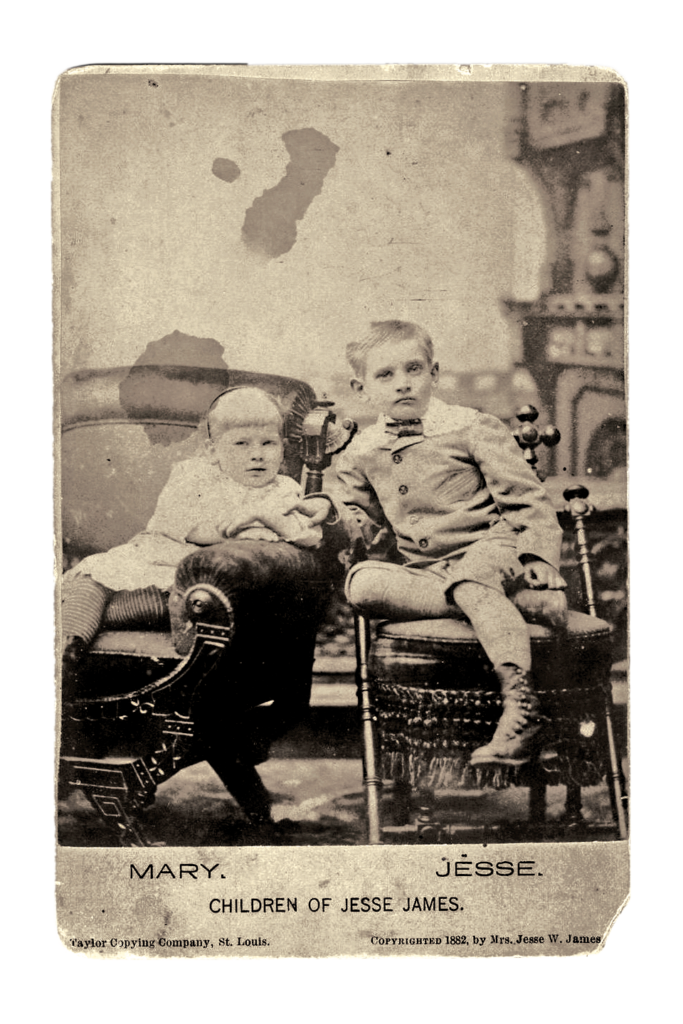

Jesse doted on his children, the Fords said, and became upset when his wife, Zee, tried to discipline them. And Jesse let it be known that he was intent on giving his kids a proper education, regardless of circumstances. It isn’t a stretch to say that what the Fords witnessed inside the James household was close to how Zee James worshipfully described her husband within an hour or so of his murder: “a kinder hearted and truer man to his family never lived.”

Not surprising considering Jesse’s narcissistic nature, the Fords noted that the outlaw was a voracious reader of newspapers, eagerly scanning their pages for references to the infamous James gang. “He wanted to be talked about and would do anything to get his name in the papers,” Charley said. “If the papers didn’t say anything about him for some time, he’d write something to them himself.”

Exploding Myths

It was various Missouri newspapers published at the end of March that provided Jesse confirmation of something he’d long known—that former gang member Dick Liddil had turned himself in and was giving state’s evidence. As the crackerjack British researcher and author Michelle Pollard has recently pointed out, this explodes the myth repeated by writers and filmmakers that Jesse first learned of Liddil’s surrender the morning of April 3, supposedly prompting the Fords to kill Jesse before he killed them. Zee James, interviewed by a reporter as her husband’s body grew cold in the front room, also well knew of Liddil’s betrayal, stating that “he has been a traitor for some time.”

While it’s clear that Jesse was quite the reader, one thing the Fords never saw him read was a book. In fact, when the majority of the contents of the little cottage were auctioned to support Jesse’s destitute family, no books were among the items sold. However, there was one book among the personal possessions initially taken from the home by the city police. It was Noted Guerrillas by newspaperman and ex-Confederate John Newman Edwards, the Jameses’ biggest defender and their pseudo press agent. Naturally, Jesse and Frank figure prominently among Edwards’ “noted.” (Jesse gave his son the middle name “Edwards” in honor of the newsman.)

The Legend Will Never Die

Whether newspapers, DNA-soaked splinters, tawdry melodramas, dime novels, movies, tacky souvenirs or questionable artifacts, people have been selling Jesse James since even before he met his fate at the hands of the Fords. The outlaw sells, of course, because we continue to buy. Jesse’s birthplace near Kearney, Missouri, and the death house at St. Joseph count visitors from all over the world. I actually visit the death house annually. There’s just something about standing in the room with the ghosts of Jesse and the Fords, imagining over and over in one’s mind that iconic moment that’s as emblazoned on the American consciousness as John Wilkes Booth’s outstretched arm holding a derringer to Lincoln’s head.

On a visit to the death house a few years ago, I spotted in the modest gift shop a box containing some old, weathered pieces of wood. The box had a paper sign on the front that read: “Original shingles from this house where Jesse James was killed. $12.50.” Could this really be? I thought. Can one still buy a piece of Jesse’s house after well over a century? A piece, so to speak, of the legend itself? I took a picture of the box—and then quickly got out my wallet.

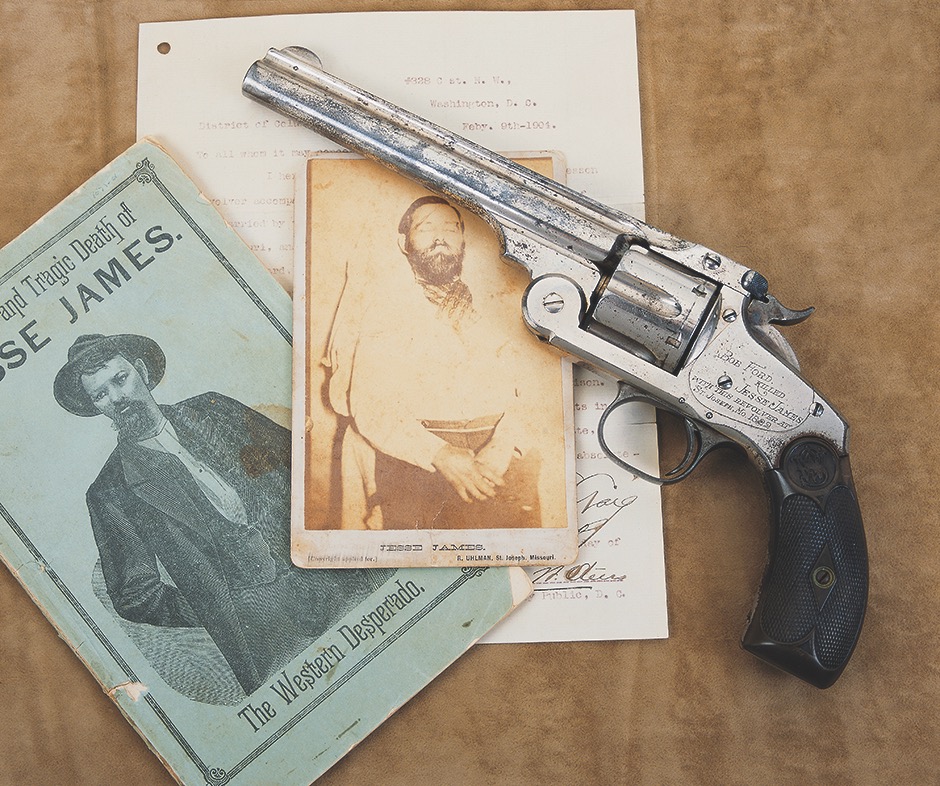

The Smoking Gun: Where is Colt #50432?

One enduring—and needless—controversy stemming from the assassination of Jesse James centers on the gun that Bob Ford used to kill the outlaw. Was it a Colt or a Smith & Wesson? The St. Joseph Western News, in its issue published on the day of the shooting, stated that Bob’s weapons consisted of “one forty-five caliber Colt’s and one forty-one caliber of the same make, but double action.” As for which of those arms Bob used to kill Jesse, the St. Joseph Daily Gazette of April 4 reported that Bob used the .45 Colt.

And then there’s the striking photograph of a seated Bob Ford taken by St. Joseph photographer Alex Lozo on April 6 in which Ford is holding a Single Action Army Colt, which appears to be nickel-plated.

The above would seem to settle the matter, but Charley Ford did create some confusion for historians when, at the coroner’s inquest held on April 5, he was quoted as saying his brother used a Smith & Wesson. Whether Charley was misquoted or simply mistaken matters little, for Charley wasn’t the one who shot Jesse. And brother Bob, in addition to not having a Smith & Wesson on his person when he fired the fatal shot, soon made quite clear the make and caliber of the murder weapon.

By May, 1882, Bob and Charley were still waiting on the promised reward for Jesse’s demise. They needed money, and it seems Bob struck on the idea of getting a loan using the famous gun as collateral. However, former City Marshal Enos Craig still retained the weapons and other property of the Fords. After some prodding, Craig finally turned over the brothers’ property on May 2. The receipt from Craig, published in the St. Joseph Herald, lists one Colt .45 and one Colt .41, the same weapons identified as belonging to Bob. Then, in Kansas City the next day, Bob signed the following affidavit in front of Justice of the Peace J. C. Ranson:

Personally came before me, J.C. Ranson, justice of the peace in and for the county of Jackson, Robert N. Ford, who, having been by me duly sworn, deposes and says that the pistol No. 50432 Colt .45 caliber here shown is the same that he, Robert N. Ford, used to shoot and kill Jesse James, at the City of St. Joseph, on the 3d day of April, 1882.

Ford’s sworn statement was published in the Kansas City Times of May 5, 1882, which added that the murder weapon was presently on display at C. Blitz’s “Famous Loan” office. Bob soon paid off the loan and retrieved his gun, for he used it on stage in the following months when reenacting with his brother their dastardly—or heroic—act.

Unfortunately, the above historical information, readily available to any serious researcher, didn’t figure in the 2003 sale of a .44 caliber Smith & Wesson revolver touted as the gun that killed Jesse James. That weapon brought an astounding $350,000 at an Orange, California, auction. Its history is traced to Corydon F. Craig, a theater manager and the son of Enos Craig. Corydon turned up in Baltimore, Maryland, with the Smith & Wesson in 1904, claiming it was the Jesse James murder weapon. According to the tale Corydon spun, Ford had given the gun to his father in appreciation for the kindness shown by the marshal while the Fords were in jail.

Corydon found a ready buyer for the revolver, who promptly sent it off to the Smith & Wesson factory to have it engraved with an inscription identifying it as the gun that killed Jesse James. Naturally, the inscription gave the

gun an air of authenticity to the unsuspecting. The revolver remained largely out of sight for several decades until it came up for auction in Lewes, England, in 1993, where it sold to an American named J. McGee for $185,493. The individual who dropped $350,000 for the spurious revolver ten years later chose to remain anonymous, but their purchase surely set a world record for the highest price paid for a .44 caliber paperweight.

And what of the actual gun that killed Jesse James, the Colt SAA #50432? In 1891, Bob Ford got into a face-to-face shootout with a man named J. D. Harden in a Walsenburg, Colorado, saloon. Bob was wounded in the foot, while Harden took rounds in his shoulder and hand. The Rocky Mountain News reported that Bob used the same gun he’d used to kill Jesse, which is certainly possible, although the News gave an incorrect caliber for the weapon. The News also quoted the town marshal as saying he intended to keep the weapons of both men as “mementos of the almost fatal tragedy.”

Whether or not the revolver Ford blazed away with in Walsenburg was his Colt #50432, it seems to be the last time Ford is mentioned as possessing the gun that killed the Missouri outlaw. Where it went from there is unknown. If not discarded or destroyed, Colt SAA #50432 is still out there, perhaps in a private gun collection, a museum or maybe even someone’s dresser drawer, waiting to be discovered. Its value today could be in the millions, so start looking!

—M.L.G.

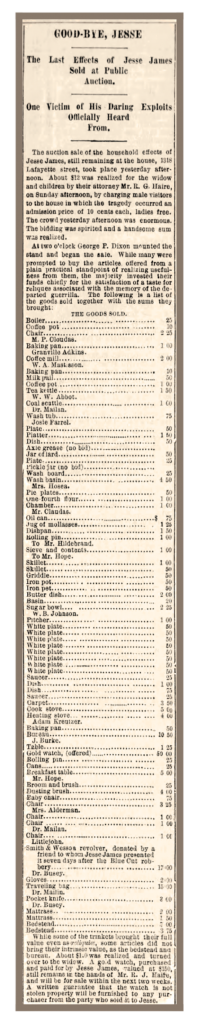

The Jesse James Auction

On April 10, 1882, a week after Jesse’s murder, a good portion of the James family’s personal property, mostly household goods, was auctioned at the hilltop cottage to benefit Jesse’s widow and two children. The St. Joseph Herald reported that the sale drew a large crowd, but it was largely composed of “lookers.” With few bidders, then, items went cheap. The total from the sale was a paltry $117.65. Below is the partial list of the items sold as published by the Herald, along with the amount each piece realized.

Copper bottom boiler, .25

Coffee pot, .10

Chair, $2.25

Dripping pan, .50

The coffee mill which little Jesse Edwards James was using under instruction of the Ford boys when they shot his father, $2.00

Milk pail, .50

Coffee boiler, .90

Tea kettle, $1.50

Coal hod, with coal carried in by Jesse just before he was shot, $1.00

Wash tub, .75

Can of kerosene, .50

Jug of molasses, $1.25

Jesse James’ dog, $15.00

Rolling pin, .50

Sieve and contents, cans, etc., $1.00

Skillet, $1.00

Skillet, .50

Griddle, .50

Iron pot, .50

Iron pot, .50

Butter dish, $2.00

Tin basin, .25

Sugar bowl, $2.25

Pitcher, $1.00

Tin plates, .50 each

Three saucers, .25 each

Vegetable dish, $1.00

Small dish, .75

Large platter, $1.50

Jar of lard, .50

Washboard, .25

The wash basin that Jesse James used a few minutes before he was shot, $4.50

Three pie plates, .50

Half sack flour, $1.00

Vessel, $1.00

Zinc, .50

Lot of cans, .25

Table, $5.00

Scrub brush and broom, .25

Brush used by Jesse James in dusting a picture at the time he was shot, $4.50

Baby’s high chair, .75

Chair, $3.25

Chair, $1.00

Revolver, with a history in connection with the Blue Cut robbery, $17.00

Pair of gloves belonging to Jesse, $2.00

Mattress, $2.00

Mattress, $1.50

Valise purchased by Jesse James in Baltimore and carried by him ever since, $15.00

Bedstead, used by Jesse and his wife, $7.00

Jesse James’ pocket knife, $3.00

Individual salt, .25

Bedstead occupied by the Ford boys, $3.75

Bloody carpet, $3.50

Leather strap from the Blue Cut robbery, .25

Cook stove, $5.00

Heating stove, $4.00

Kitchen table, $1.25

Bureau, $10.50

Jesse James’ gold watch was offered, but there was only one bid, $50.00, and the watch was not sold.

—M.L.G.