Back in 1989, when Life Magazine asked Hollywood legends like James Stewart, Bette Davis and Olivia DeHavilland to pick their favorite young stars of the day, Joel McCrea selected Kevin Costner. He described the Field of Dreams star as “a little Clark Gable, a little Gary Cooper, a little Jimmy Cagney. A boy like that is ideal for a colorful Western.” McCrea was right, although at that time Costner had only played a supporting role in Lawrence Kasdan’s very colorful Western epic, Silverado. The similarity in McCrea’s stoic appeal and his own wasn’t lost on Costner, who’d replied, “Joel and I are the kind of leading men who say, ‘Yup,’ and ‘Nope’ and ‘Where’s the horse?’”

Costner liked hearing McCrea’s words again, three decades later. “I remember enjoying Joel McCrea a lot. He was a really humble guy. Joel was constantly trying to give his roles away to Jimmy and to Gary and to other people, saying that they’d be just right for that. I’m pleased that he would say something like that about me.”

Does he still see himself as a “yup” and “nope” leading man?

Costner laughed. “Sometimes Westerns get reduced to that. In fact, the Westerns that I depend on are really dependent on the word, but the reality of the ‘yup, nope’ is there’s a level of economy that comes with language that has weight. They’re very literate. I mean, it’s our Shakespeare. Sometimes a couple lines can leave no doubt as to what someone’s intention was. I like classic, so I respond to a Liberty Valance, Searchers and certain things that occur in the [John Ford Cavalry] trilogy.”

Of course, Costner entered the Western film in an era when the genre had been declared legally dead.

“There were a lot of Westerns that I didn’t enjoy back then, and there were ones that stayed with me forever. And it’s the same way now. A lot of times they missed the mark for me personally, because they’re rushing to get to the gunfight. Whenever Westerns start out with a big slaughter, and then one man has to go on some vindictive hunt… I mean, that’s true, but I think it’s a convenient and too easy way to start Westerns. In the right hands, something like that can be dramatic, and in other hands, they miss the point.”

— Courtesy Columbia Pictures —

What was it like to get Silverado, his first Western role?

“Imagine standing in the best spot in a river on a really firm rock, and knowing you’re just going to fish there all day. This is everything I need right here. It was a blessing.”

Not that it wasn’t a challenge playing Jake, a loud and rambunctious cowboy who is the antithesis of his more familiar, thoughtful, soft-spoken heroes.

“Jake was just so full of juice that it was difficult to figure out who he was relating to in the scene, because he was talking at one pitch level. I remember thinking, I know exactly how to play those other parts, but how am I going to play this guy? And I found a way: I basically tried to compete with the horizon,” he said with a laugh, “the outdoors itself, and have a sense of fun. I was really lucky to be able to play that part. It did a lot for me.”

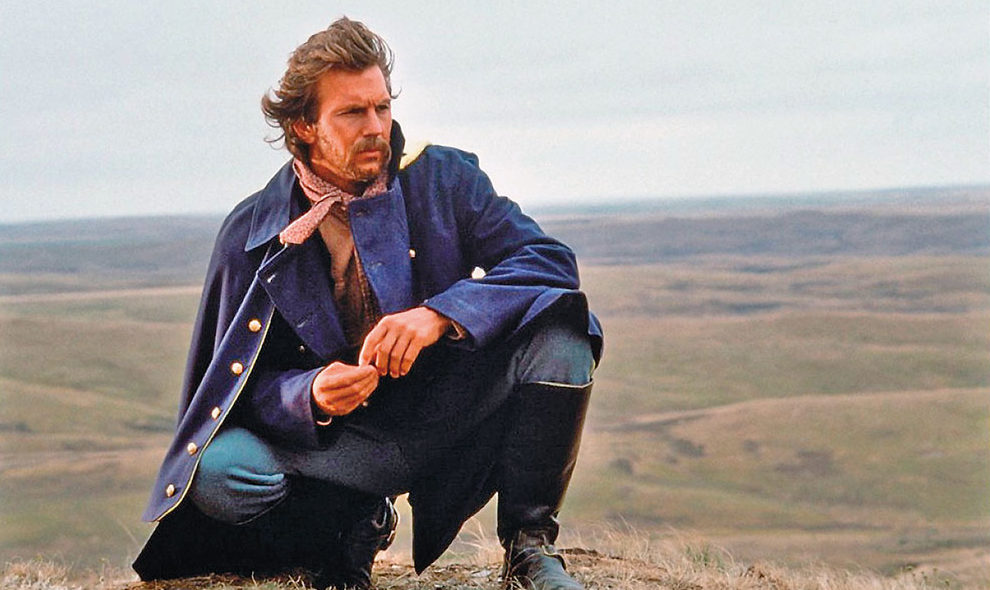

In 1990, Costner would become a producer and director as well as star in the most Oscar-honored and financially successful Western of all time, Dances With Wolves. It’s a wonderful film that helped rejuvenate the genre, and brought women back into the audience.

— Courtesy Orion Productions —

“I was prepared for people to like the movie because I liked it. I wouldn’t have put my money in, I wouldn’t have put my time in, if I didn’t think that if I made it correctly, people would relate to it. The surprise is that something can be a runaway hit, that it catches that kind of air, that it has that level of momentum.”

Nine years after Silverado, Costner would act again for director Lawrence Kasdan, as Wyatt Earp.

— Courtesy Warner Brothers —

“Larry’s a real thoughtful writer. Silverado was a matinee type of movie; Wyatt Earp was a darker look at a person’s life, and really thoughtful writers get past the gunfight and understand the makeup of what kind of guy actually survives, versus the kind of people that don’t survive. Even capable people don’t survive because of the randomness of violence; the wrong place at the wrong time. People that look carefully are always interested in why the Wyatt Earps never got hit by a bullet.”

In 2003, Costner directed his second classic, Open Range, which starts with a look at the day-to-day hazardous life of four cattle drovers.

— Courtesy Touchstone Pictures —

“The plot is simply: a storm came, and it sunk their wagon, it scattered their cattle. To go on, they have to re-provision and gather their cattle. So they almost escaped danger. That danger was always there, in the town. But the moment it rained on them, they were stuck. I love that plots can come out of that. The idea of friends knowing each other a long time and not communicating intimate information amused people, but we both know it to be true. People were very guarded, [going] back to the Civil War. People fished for information because some carry these grudges, these vendettas for the next 50 years. You’ll see that as a theme in all my work.”

To put it mildly, grudges and vendettas were a theme of his next Western project, 2012’s Hatfields & McCoys, for which Costner’s performance as Devil Anse Hatfield won him an Emmy and Golden Globe for Best Actor.

Did Costner mind that, while clearly the protagonist, he wasn’t a hero?

— Courtesy Paramount Television —

“I’ve played a lot of things; I played serial killers. But those characters [in Hatfields] that survived out there, in this case, are authentic, real. They are dark; they’re hard. They’re men of their time period. And I enjoy that. I don’t flinch from any of it.”

In 2018 and 2019, Costner has done a pair of contemporary Westerns back-to-back. Last summer, for Paramount Television he starred in the series Yellowstone, which will return for season two next summer. Costner’s character, John Dutton, runs the largest family-owned ranch in America, bumping up against Yellowstone National Park, and is besieged by the government, an adjacent Indian reservation and land developers.

Would Costner call rancher John Dutton a man out of his time?

“Well, a man out of his time, and time catching up with a way of life. He’s having to act like a current day CEO, but he’s mired in the way that he would hope that it could be. It’s a critical moment in his life, as a lot of different forces are coming for the property. And the biggest blow to this character is that the family’s really dysfunctional as he faces all these things coming at them. So it’s a boiling pot when you come in, when we start the series.”

While Dutton is a strong character, he’s also vulnerable, even frail at times.

“Well, as you play somebody that’s at that particular age, those things are always looming. We don’t know when they’re gonna come. I think that you see how he actually deals with those issues in a very straight-up way.”

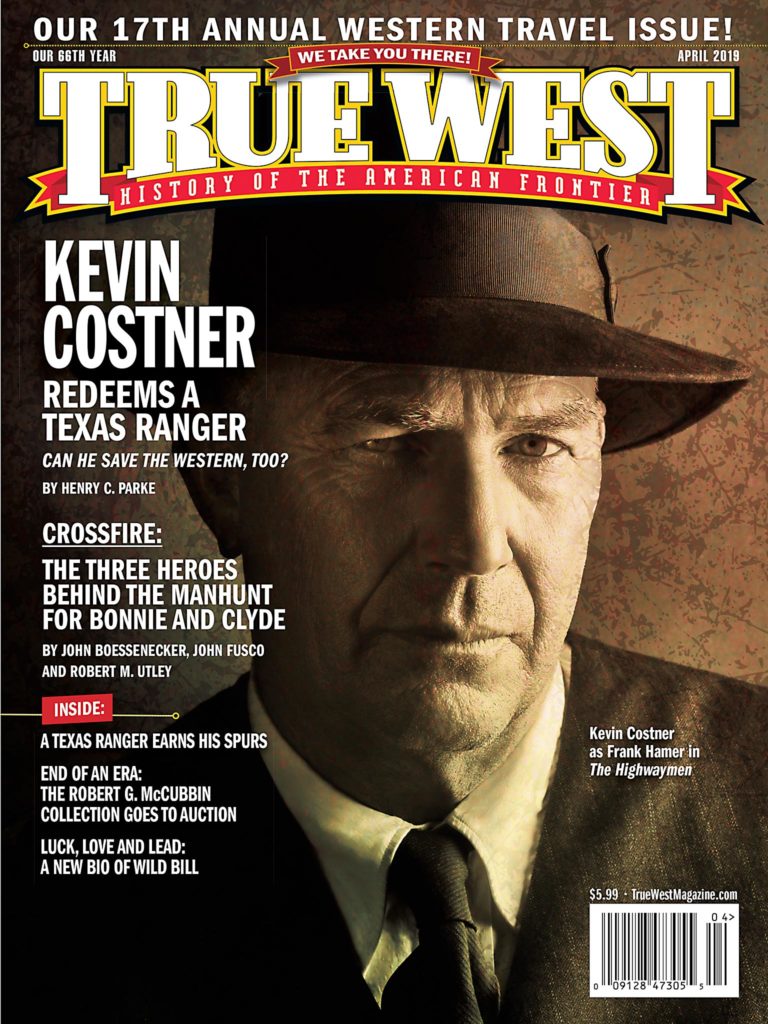

In April 2019 Costner will star for Netflix in the movie The Highwaymen, in which he and Woody Harrelson play real-life Texas Rangers Frank Hamer and Maney Gault, who came out of retirement to track down Bonnie and Clyde. The truth was much different from the Warren Beatty film version.

— Courtesy Netflix —

“Hamer’s wife sued for defamation, said, ‘My husband’s a hero. You have no business creating him out of two characters.’ And knowing that she was in two shootouts with him, Warner Brothers settled.”

What attracted him to the project?

“It’s always the writing. I thought it captured this guy and that time, and it was interesting to try to understand the men that were chasing these legendary bandits. It was just a whole other side of it, to see the man-hunters without radios, without cooperation state-to-state. You know, Rangers were almost like Spartans—they’d send a single Ranger to towns to take ahold of the situation. Seeing the Rangers evolve from on horse to automobile, knowing they’re filling out expense reports, going to chase somebody down and they have their own way of doing it…I just I thought to myself, this was a moment, this was a man that I could play.”

— Courtesy Netflix —

Was Frank Hamer a hero in the Wyatt Earp mold?

“Well, I think that they had a unique way of dealing with situations. You can look at whatever their background is and question their techniques and what they had to do in their times. But whenever we do that, and we don’t put ourselves back in that time, we do ourselves a disservice as well as them.”

— Courtesy Netflix —

Would he like to make another Western?

“I have a Western that I really want to make; I just can’t find the rich guys that want to make it—an epic Western. I want to shoot three movies, all about the same story, at the same time, three separate movies coming out like every four months. And probably lead to the fourth one, which was the one that spawned the first one. So it would be four movies. Now, will I get to do it? I don’t know, but that’s where my heart is. So if anybody wants that same thing, they can come make that movie with me.”

Henry C. Parke, Western films editor for True West, writes Henry’s Western Round-up online. His screenplay credits include Speedtrap (1977) and Double Cross (1994), and he’s done audio commentary on a fistful of Spaghetti Westerns.