–Courtesy Library of Congress –

Few would argue that names made a difference in the Old West. The easy-on-the-tongue alliteration of “Jesse James,” the rhythmic cadence of “Billy the Kid,” the romance conjured by monikers such as “Medicine Bill” and “Bear River Tom.” All gilded the image and lent legitimacy to the legends.

So when confronted with the name Marion Columbus Hedgepeth, one may be inclined to dismiss its owner out of hand—especially when he and his gang were known as the “Hedgepeth Four.” That sounds more like a jazz quartet than an outlaw band. But outlaws they were—and as deadly as any who achieved greater notoriety.

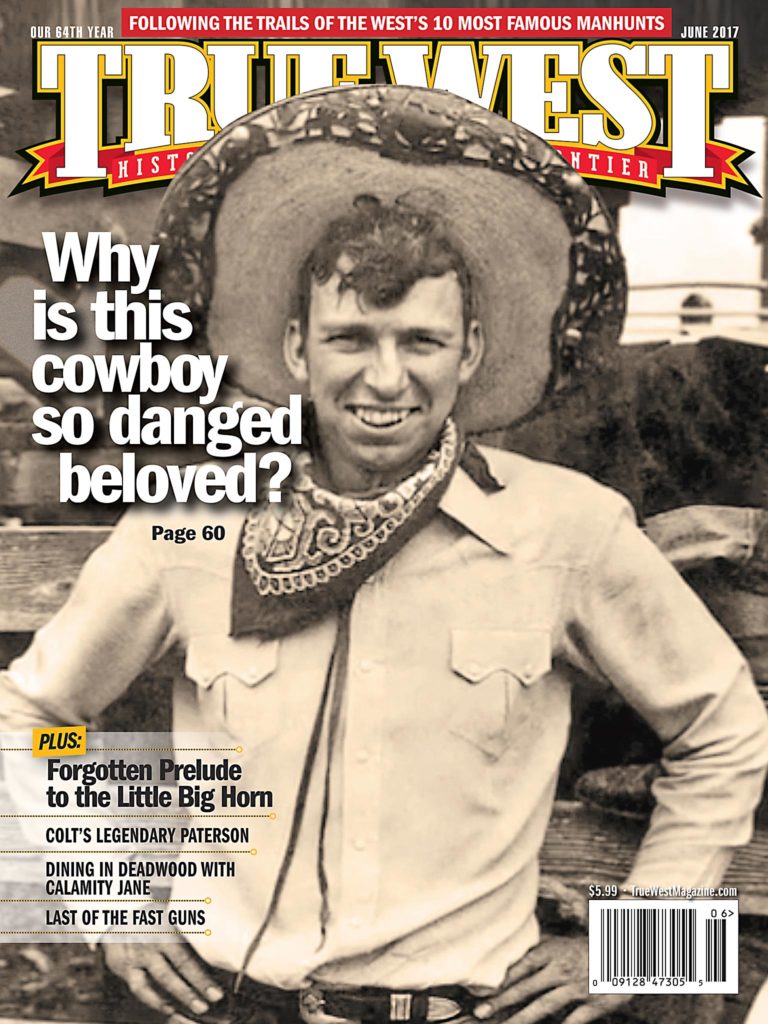

Once the first decade of the new century was nearly over, all the Old West’s most notorious pistol fighters— “Wild Bill” Hickok, Ben Thompson, King Fisher, Wes Hardin, Bill Longley and their ilk—were long gone. In more than just a poetic sense, Hedgepeth became the last of the fast guns.

The Road to Crime

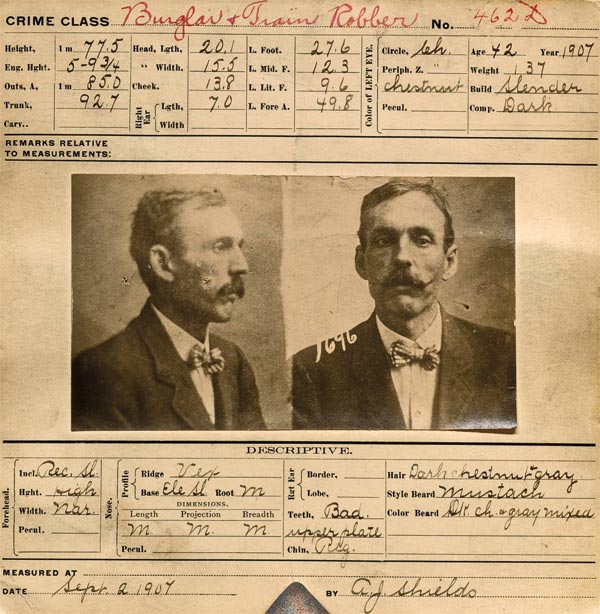

Born in 1856 in Prairie Home, Missouri, Hedgepeth left home at 15 and worked briefly as a cowboy in Colorado, Wyoming and Montana. He exhibited larcenous tendencies at an early age and was soon wanted for horse theft, cattle rustling and bank robbery. In 1889, after serving a seven-year prison stint for theft, he relocated to the “Seldom Seen” section of Kansas City, Kansas (so-called because the police were seldom seen there), and formed a gang of train and bank robbers.

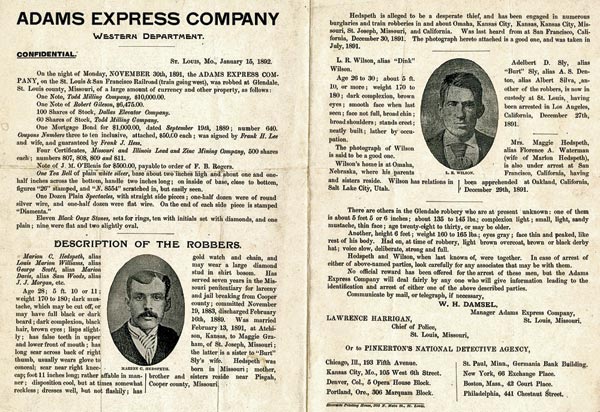

For a while, the Hedgepeth Four gang was both successful and innovative. Consisting of Hedgepeth, Lucius R. “Dink” Wilson, James “Illinois Jimmy” Francis and Adelbert “Bert” Slye, the gang was reportedly the first group of outlaws to use nitroglycerin to blow up safes and express car doors.

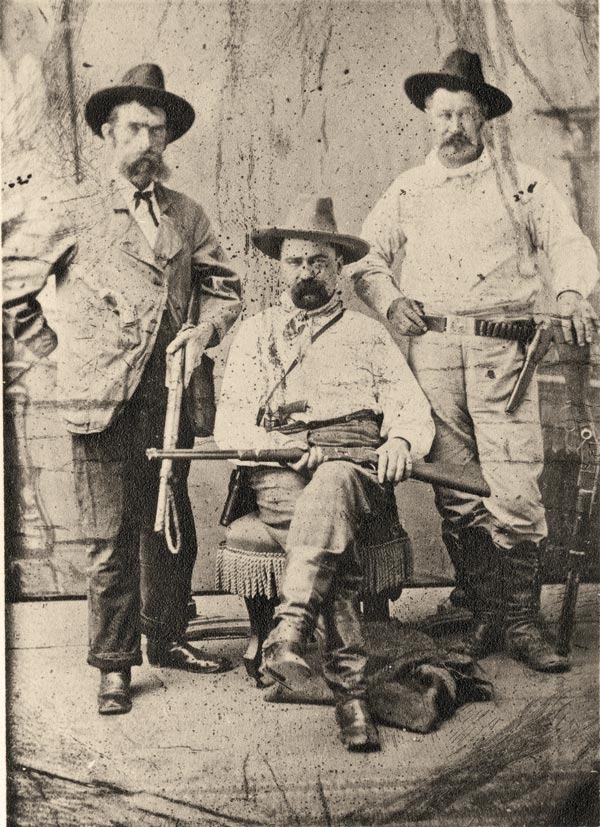

In addition to being a practiced thief, Hedgepeth was one of the West’s fastest and deadliest shootists. William Pinkerton, head of the famed detective agency’s Western Division and a man who had met more than his share of desperadoes, commented on Hedgepeth’s “incredibly fast draw,” adding that he was “bad clear through.” Pinkerton recalled seeing Hedgepeth draw and fire his revolver, and then shoot his opponent through the heart, after the man had already unholstered and leveled his pistol.

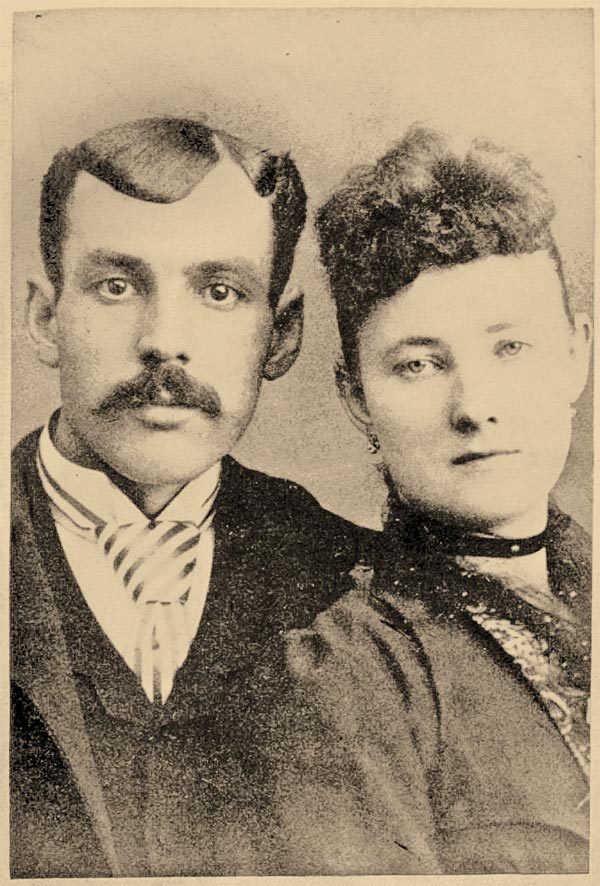

The tall, dark-haired Hedgepeth didn’t dress the part of a typical Western badman. He was, in a word, elegant; according to an Adams Express Company “Wanted” handbill, he dressed “well but not flashily.” Hedgepeth prided himself on his expensive suits, diamond stickpins and shirt studs, costly shoes and a hat style that earned him the nickname, the “Derby Kid.” He was also known by other impressive aliases, including the “Handsome Bandit,” “Debonair Bandit” and “Montana Kid.”

Most Dramatic Robbery

Hedgepeth’s train robberies were well-planned models of derring-do. The outlaws robbed three trains in as many weeks in November 1891, in Omaha, Nebraska, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and Glendale, Missouri. The last was by far the most dramatic—it ultimately led to the end of the Hedgepeth Four.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

As the St. Louis & San Francisco Railroad express train left the station in Tower Grove, Missouri, on the chill night of November 30, four men boarded the front and rear platforms of the express car, located behind the coal tender.

Donning masks, the two on the front platform—Hedgepeth and a colleague—crept over the top of the coal tender and into the cab of the locomotive. They pulled out their loaded revolvers and confronted the engineer and fireman.

After ordering that the train be stopped, Hedgepeth shouted to the Adams Express Company messenger to open the express car door. The messenger refused, yet the bandit was not deterred. He set a charge of nitro and, according to a Pinkerton brief, “blew the door down with such force that the messenger was seriously injured….”

Hedgepeth then blew open the safe, removing some $20,000 in cash and valuables.

Meanwhile, Hedgepeth’s colleagues remained outside and “beguiled their time with shooting…through the windows of the Saloon car..,” the Pinkerton brief reported. Then, loot in hand, “with a final volley of shots” the gang “escaped through some thick woods adjoining the tracks.”

Plunder in James Gang’s Territory

The fact that Glendale had been the site of one of Frank and Jesse James’s robberies 12 years earlier was not lost upon the local papers. The day following the robbery, the Omaha Daily Bee ran a front-page report under the outraged headline, “In Jesse James’ Territory!” “Train robbers invade Missouri,” the article trumpeted, “and boldly hold up an express.”

As was policy, the Adams Express Company immediately called in the Pinkerton Detective Agency. Allan Pinkerton, who founded the agency in Chicago, Illinois, in 1850, had died in 1884, but the agency was in the able hands of his sons, William and Robert. They moved the detective game forward with a project their father had begun, a database of mugshots, newspaper clippings and criminal histories—this was the precursor for the FBI’s criminal database.

From the physical description of the leader, as well as the gang’s method of operation, the Pinkertons identified the robbers as Hedgepeth and his associates. By this time, however, the gang had quietly left for California.

Through exemplary detective work and dogged determination, the Pinkertons tracked down three of the gang members.

In January 1892, they fatally shot Francis while he resisted arrest in Pleasanton, Kansas; he had just robbed another train, killing a lawman and netting all of $75.

They captured Slye in Los Angeles, California. He was sentenced to 20 years in prison.

Hedgepeth got caught because of someone closer to home. The Pinkertons tracked him down through a letter written to him by his wife and sometimes accomplice, Maggie. He was packing two pistols when the agents found him at a San Francisco express office, but he ended up trapped and overpowered.

Only Wilson managed to elude capture…for a time. He and his brother made their way to Syracuse, New York, where they staged a series of burglaries and bank robberies. When a lawman sought to question them, Wilson shot and killed him, for which he was eventually executed in New York State’s electric chair.

Rotting Away in Prison

Hedgepeth got a 25-year sentence in the Missouri State Penitentiary. He had no intention, however, of staying in prison.

“He Had Almost Gained His Freedom,” reported The New York Times on December 17, 1893, adding: “In some unknown manner he had secured possession of a saw and file, with which he cut the bars on his cell door.”

Just as he was climbing to a window leading to the street, however, his escape attempt was foiled.

Back in prison, Hedgepeth struck up a jailhouse friendship with a man calling himself H.M. Howard, who was incarcerated on a swindling charge. Howard was about to be released, and he brought Hedgepeth in as a partner on a life insurance scam.

But when Howard later failed to pay him his promised share, Hedgepeth added “informer” to his list of callings. As it turned out, Howard, better known to the law by his alias, “H.H. Holmes,” was really Herman Webster Mudgett, the fiendish serial killer who had murdered as many as 200 young women in Chicago. The law caught up with Mudgett, and he subsequently died on the gallows.

In 1904, Hedgepeth, suffering from consumption, wrote an impassioned letter to William Pinkerton, pleading to be considered for a pardon: “I’ve stolen thousands of dollars. What good did they do me?… Everything is gone except my poor old carcas [sic] and it is racked by an incurable disease…. That’s what they call graft. I’m tired of it….”

and signed both of them

“Marion C. Hedgepeth.”

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

“Ready to be Good”

Hedgepeth must have gotten a hold of William when he was in a charitable mood. The Pinkerton head interceded with the governor, and the 45-year-old Hedgepeth walked out of prison on July 4, 1906.

“[H]e looked like a skeleton and appeared 60 years old,” reported the Kansas City Times. “His jaws were sunken, his eyes deep set and his hair thin and gray. He said he was ready to be good.”

– Courtesy Missouri History Museum –

Hedgepeth made an honest, if short-lived, attempt to go straight. After briefly returning to Prairie Home to visit his ailing mother, he worked as a shoemaker and sometimes-paid informant for the Pinkertons.

His resolve weakened, however, and he was arrested the following year for robbing a safe in Council Bluffs, Iowa, for which he served a year in jail.

Hedgepeth decided to ring in the New Year as one for outlawry when, on New Year’s Eve in 1909, he attempted to rob a saloon in Chicago, Illinois. A lawman suddenly appeared in the doorway, aimed his pistol at Hedgepeth and ordered him to surrender. The sick and aging outlaw reflexively drew and fired—but the old days were gone, and with them, some of the old skills. His shot missed; the lawman’s didn’t.

Hit in the chest, Hedgepeth continued to fire, without effect. The lawman shot again, hitting him in the head, and what remained of the “Derby Kid” fell mortally wounded, his pistol in his hand.

The outlaw was taken to St. Anthony’s Hospital, where he died. Hedgepeth’s death certificate lists the cause of death as “shock and hemorrhage,” and in the space reserved for “occupation,” the Cook County coroner wrote “shoemaker.”

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

The man most knew as the “Derby Kid” was buried in Dunning Cemetery, a “potter’s field” filled with tens of thousands of Chicago’s nameless dead, from the prison, the Cook County Poor Farm, the insane asylum and the Chicago State Hospital. No stones marked the graves.

William Shakespeare famously asked, “What’s in a name?” Apparently, when it comes to Old West desperadoes, a great deal. The renowned Western historian and biographer Robert K. DeArment, in describing the career of legendary bandit Sam Bass, wrote, “Bass might be completely forgotten today had he been born with a name like that of a certain bank and train robber whose daring exploits spawned headlines in the 1890s but who was not immortalized in song…. No one ever wrote or sang ‘The Ballad of Marion Hedgepeth.’”

Ron Soodalter is a published author and magazine reporter who also writes a monthly column in America’s Civil War. He serves on the Board of the Abraham Lincoln Institute and is a member of the Western Writers of America and the Wild West History Association.