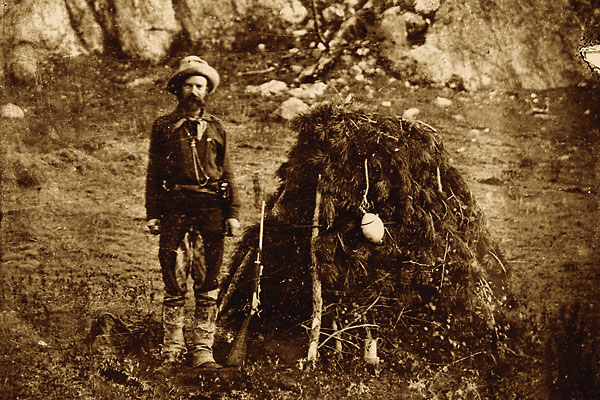

Valentine T. McGillcuddy, weak and on the verge of becoming an alcoholic after a stint as a doctor at the Wayne County Insane Asylum in Detroit, started a new career as a topographical engineer and cartographer when he was in his early 20s.

He worked on surveys of the Great Lakes and the city of Chicago, following its great fire in 1871. He first saw the Great Plains as a member of the Northern Boundary Survey in 1872.

McGillycuddy served with the U.S. Northern Boundary Survey team from 1872 through the summer of 1874. He and the other topographical engineers worked their way west 860 miles from Lake of the Woods in northern Wisconsin to the Rocky Mountains at what is now Glacier National Park in Montana.

We will start our journey at Fort Totten, near Devils Lake, North Dakota, where in the fall of 1872 the surveyors were told to return to a swampy area between Lake of the Woods and the Red River to complete that boundary survey section. The ground that earlier had been too wet, would now be frozen.

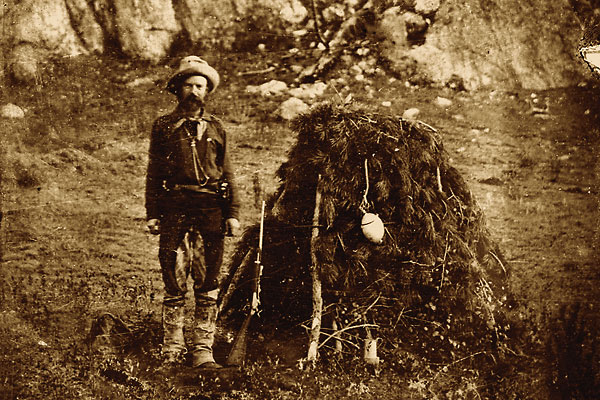

Like the other men on the winter survey party, McGillycuddy likely wore Sioux-style moccasins that were several sizes too large. Before putting on the moccasins, the men encased their feet in “one or two pairs of woolen socks, then a pair of ‘neeps’ [slippers made of blanket], then a square piece of blanket wrapped several times around the foot from heel to toe.” Finally the men added their oversized moccasins, “more to keep the blanket and slipper in place than for any other purpose,” one man said.

They concluded their work, and then returned to Detroit, where from March 1 to June 1, 1874, some men worked on their field observations while McGillycuddy was engaged in “plotting and draughting.”

The following summer he led one of the topographical parties, returning to North Dakota and working west from there toward the Rocky Mountains. He ran the survey lines for what would be the northern border of Montana. Sometimes finding the way blocked by massive herds of buffalo, McGillycuddy later recalled, “Buffalo dotted the plains as far as the eye could see. Often we had to suspend astronomical observations at our stations located at 20 mile intervals because the vibrations from the drumming hoofs of herds nearby shook the instruments.”

He met Maj. Marcus Reno and Lakota Chief Sitting Bull during the summer. Later that fall, as the topographical parties returned down the Missouri, he met Gen. George A. Custer at Fort Abraham Lincoln.

Outset at Devils Lake

Our route begins at Devils Lake. We will travel south to Fort Totten on Highway 57 then south to Jamestown, North Dakota, on U.S. 281 before turning west on I-94 to Bismarck. From there we travel north on U.S. 83 to Minot, then west on U.S. 52 and U.S. 2 to Havre, Montana, before turning south on U.S. 87 to Fort Benton. The survey parties ended their work there in 1874 and took a ride downstream.

McGillycuddy traveled to Washington, D.C., and began drawing maps of the border country. But his tenure at the map table was short-lived. John Wesley Powell, directing the Geographical and Geological Survey of the Rocky Mountain Region for the Department of Interior, called McGillycuddy into the field again.

Mapping the Black Hills

This time he traveled west by train to Cheyenne, in Wyoming Territory, and went overland to Fort Laramie, where he joined Lt. Col. Richard Irving Dodge of the 23rd Infantry and the leaders of the scientific party: geologists Walter P. Jenney and Henry Newton, both from the Columbia School of Mines in New York, and astronomer Horace P. Tuttle, of the Cambridge Observatory in Massachusetts.

The Black Hills Expedition, commonly called the Newton-Jenney Expedition, spent the summer of 1875 roaming the Black Hills. McGillycuddy surveyed and gathered information for the maps he would eventually produce, among the first prepared for the region. While there he climbed Harney Peak and named many of the other physical features in the Black Hills. The primary purpose of the expedition was to determine the extent of gold deposits in the region, which at the time was Lakota territory and officially off limits to mineral development.

Our route along this portion of McGillycuddy’s trail takes us from Bismarck south on U.S. 83 to Pierre, South Dakota. Travel west on I-90 to Rapid City and Deadwood, a community spawned shortly after the Black Hills Expedition concluded, in spite of tribal rights to the area. From Deadwood, we will follow the Newton-Jenney route in reverse, by heading south on U.S. 85 through Newcastle and Lusk, Wyoming, to Fort Laramie, where the expedition had organized, and then on to Cheyenne. At the time that city was the capital of Wyoming Territory, and a major terminus on the Union Pacific Railroad.

At the close of the 1875 expedition, McGillycuddy returned to our nation’s capital to draw the maps. In May 1876, he had another summons. This time, his ability as a doctor drew him to Gen. George Crook, who had met McGillycuddy on the Black Hills Expedition. Crook was organizing a military incursion into the Powder River Basin.

Treating the Wounded

McGillycuddy returned by train west to Cheyenne, where he met both Wild West showman William F. Cody and gunfighter James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok. He continued by rail to Medicine Bow Station and then traveled overland to Fort Fetterman. The doctor spent a few weeks at the fort, treating men wounded during Crook’s battle at the Rosebud, before he followed the troops into the field and joined Crook near Goose Creek. He would remain with Crook throughout the remainder of the summer and fall, working as assistant surgeon when Crook’s detachment moved east and then south into the Black Hills, engaged in the Battle at Slim Buttes and eventually arrived at Camp Robinson in October.

Our route from Cheyenne circles to the west on I-80 to Laramie, and then on U.S. 30 to Medicine Bow. You can take back roads to Fort Fetterman, or you can follow the highway by backtracking through Rock River to Bosler Junction and then taking Highway 34 through Sybille Canyon to I-25 at Wheatland. Follow the interstate west to Douglas, where you’ll take Highway 93 to Fort Fetterman.

In following McGillycuddy’s route to join Crook, travel back to I-25 to Casper and continue north to Buffalo, near where McGillycuddy joined the general. From here the Bighorn and Black Hills Expeditions traveled north toward the Yellowstone River. McGillycuddy and other doctors with Crook treated survivors of the Little Bighorn Battle, and then they traveled east before turning south toward the Black Hills. Our route takes us north on I-90 through Sheridan, Wyoming, and Hardin, Montana, site of the Little Bighorn battle, then east on I-94 to Miles City and on U.S. 12 to Bowman, North Dakota, before turning south on U.S. 85.

The troops engaged in the Battle of Slim Buttes, after which McGillycuddy took care of wounded soldiers as they engaged in what was known variously as “Horsemeat,” “Starvation” or “Mud” march. The starving troops were forced to kill their horses and mules for food, and to tramp through sloppy, muddy conditions caused by incessant rain.

Journey to Crazy Horse

Our route takes us back to Deadwood and Lead, and then south on U.S. 385 through the Black Hills into Nebraska. Turn west on U.S. 2 near Chadron to travel to Fort Robinson. This post, now a Nebraska State Park just west of Crawford, also has the location of nearby Red Cloud Agency, which served the Lakotas under treaty terms set forth in 1868 at Fort Laramie.

McGillycuddy first saw Red Cloud Agency on October 9, 1875, when he served with the Newton-Jenney expedition. The distribution of treaty annuities created a beehive of activity at the agency. When the doctor returned with Crook’s troops in the fall of 1876, he was soon assigned as assistant surgeon at Camp Robinson.

Dr. McGillycuddy would spend the next two decades in the Black Hills region. He worked as a doctor at Camp Robinson (later Fort Robinson) during the summer of 1877, treating both soldiers and Indians who had surrendered and become attached to Red Cloud Agency. He cared for Crazy Horse’s wife Black Shawl Woman, who suffered from tuberculosis. He came to know the Oglala leader quite well from the time of his surrender in May. He also cared for Crazy Horse during the hours after he was stabbed on September 5, 1877, until the chief’s death shortly before midnight that evening.

The doctor continued serving both military and Indian patients for another two years, moving with them as they abandoned Red Cloud Agency in northwest Nebraska and established a new temporary agency closer to the Missouri River in South Dakota. He took part in military excursions to round up the Northern Cheyennes led by Dull Knife and Little Wolf, after those people fled the Darlington Agency in Indian Territory (Oklahoma) in the fall of 1878. He was living at Camp Robinson until just before Dull Knife and his followers broke away from the barracks where they had been incarcerated following their surrender to troops.

Indian Conflict

In January 1879, McGillycuddy was in Washington, D.C., where he caught the eye of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. He returned to the new agency being organized for the Lakotas—Pine Ridge—in March 1879, in a new role: Indian Agent.

The next seven years were the most tumultuous of his life as he managed Pine Ridge with an iron will, often coming into conflict with Red Cloud, the venerable old leader of the tribe, who resisted every effort Agent McGillycuddy made to force the tribespeople to assimilate into white culture. During this period, McGillycuddy himself said he was the “most investigated” agent in the Indian service. No charges were ever brought against him that were proven.

Eventually removed from his position for political reasons—he refused to replace his long-time clerk with a political appointee—McGillycuddy and wife Fanny, who had been with him at his various postings since 1876, relocated to Rapid City. He became the town’s first mayor and the first president of the South Dakota Schools of Mines and Technology. He also served at the behest of South Dakota Gov. A.C. Mellette during the troubles leading up to Wounded Knee during the winter of 1890-91, treating both soldiers and Indians after that incident.

Our route turns east from Fort Robinson through Chadron, Nebraska, on U.S. 20. Turn north on Highway 87 to Pine Ridge and east on U.S. 18, before you turn north on Big Foot Trail to Wounded Knee.

Standing Tall

After Fanny’s death in Rapid City, McGillycuddy pulled up his Black Hills roots and relocated to California, where he spent the remainder of his life. He remarried in 1904, had a daughter, also named Valentine, and recounted his life story to new wife Julia (who wrote the 1941 biography McGillycuddy, Agent).

He died in 1939 at age 90. His cremated ashes were placed in a crypt atop Harney Peak in the Black Hills. The mapmaker/surgeon had been the first white man to climb it in 1875.