I’ve heard it said countless times that if you can punch cows in Yavapai County, Arizona, you can punch cows anywhere.

The rough, steep, brushy, boulder-strewn terrain provided the tests that young Monk Maxwell passed with soaring colors. He apprenticed with his father Virgil, who tied his catch rope hard and fast, Texas style and made super-handling horses at the Circle Bar Ranch. Then way back of beyond, on the Yolo Ranch run by a cowman deluxe, his uncle Gene Smith, Monk reveled in the demands of the country and cattle, made a top hand and rose to the rank of jigger boss, second in command to the ranch foreman.

When I learned of Monk in the late 1960s, his young family had brought him in a bit closer to civilization, to the Wineglass Ranch in the Chino Valley-Big Chino area. I first photographed him at the Del Rio division of the Wineglass. When Monk trotted toward me on his fine buckskin mount, what caught my attention was the swaying motion of the long eagle bill tapaderos, fancy leather stirrup covers, my first live sighting of such elegant appurtenances. This gentleman of the range was not at all what I was accustomed to seeing in my rather limited experience in the cow countries of Texas and Arizona. Flat-brimmed hat. Slick-fork saddle with no flank cinch. Fancy silver bit. Braided rawhide reins with silver chains. Clearly, my education was far from complete.

Naturally, I asked Monk about his horse gear. “It’s California style, and it goes all the way back to the old-time vaqueros,” he told me. “Dunny’s packin’ a spade bit [a bit that contacts the roof of the horse’s mouth, versus the curved mouthpiece of a curbed bit]. It took me quite a while to get him through the stages to where he now handles like a dream. The saddle’s a three-quarter single rig, Weatherly A-fork. I use a long rope and take my dallies.”

He went on to explain that vaqueros have long been known for their skill and patience in training ultra-responsive, “trigger-reined” horses. This result was achieved in three progressive steps over a lengthy period of time. The horse was started in a hackamore with a simple noseband, the bosal, with reins. Next came a lighter bosalillo, plus a bit in the mouth, with reins on both, called the two-rein. Last came only the bit, and the horse was declared “straight up in the bridle.”

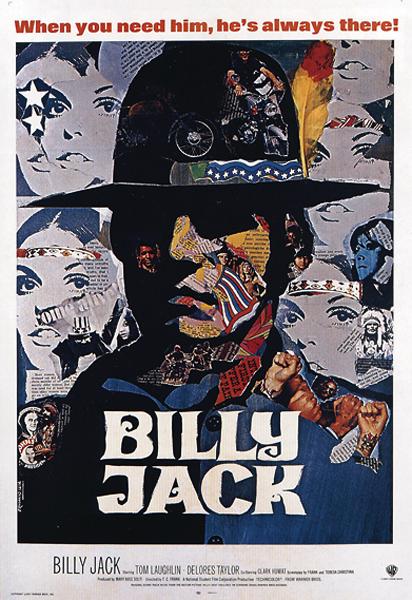

Quite a few years would pass before I rode and worked cattle, in fairly easy country, with Monk, but my good first impression of him was with me to stay. One day at Prescott College, where I taught photography, the advance man for a movie company just happened to run into me. Did I know anything about locations, livestock, etc? “Yes, but you really ought to hire Monk Maxwell. He knows the country and can fix you up with anything you need.” They did, and Monk delivered as advertised, even becoming one of the on-screen “baddies” in the 1971 low-budget cult film Billy Jack.

“He was up, down, all over the place, absolutely fearless. Just like a little monkey.” That’s what Dorothy Maxwell told me about her son, Virgil Jr., when I had asked her the origin of the name Monk. That brand of nerve and athleticism was to serve him well throughout his freelance career of catching and bringing in cattle that had “gone to the wild” in ranching’s nether reaches.

Over the years Monk ran a couple of ranches and even worked a much-despised stretch as a transcontinental trucker. But mostly he prowled remote mountains and canyons, usually on contract with ranchers who had wily cattle way back in the rough stuff that had eluded normal roundups. Since I never had the opportunity (nor the mettle) to accompany Monk on one of his wild-cow forays, I simply asked questions and took note of his descriptions and lore.

A gig might go like this: Trail up some errant bovine, say a maverick bull with several years growth and horns to match. Get him roped and maneuvered up close to a tree, and sufficiently “fouled” to be able to safely (a relative term, at best) dismount and anchor him to the tree. Tie el toro (the bull) so he will neither choke nor escape, then saw off enough of his horns to render them blunt. Ride away, perhaps to find more critters, but in any case to leave the captive to make either war or peace with el árbol (the tree). Return later and lead the chastened bull, and possibly other cloven-hooved companions, downrange to a corral or stock trailer.

Some years ago, Monk was leading a renegade bull down a rough, snow-covered mountain. The bull rammed Monk, breaking the cowboy’s ankle and nearly sending his horse off a bluff. He led the bull nine miles down to a corral, then rode another 11 back up the mountain to his camp to get his pickup and drive into town to a doctor. A week later he was back on the mountain, horseback, with his leg in a cast, chasing wild cattle.

“If you’re gonna make a living gathering wild cattle, you have to know how to get all this done working alone,” Monk explains. “When I’m roping, I like for my run to be uphill. Once I have something caught I get on the uphill side, so if we get charged, my horse and I have gravity on our side. If you’re riding up to something wild in the brush, never approach from the downhill side, because if he charges, you don’t want him to have a momentum advantage. If you have to turn away and your horse hangs up in the brush, you’ve had it. If you end up on the bottom of the wreck, you can get killed.

“I’ve been able to get my job done because of the careful schooling I’ve given the horses and mules that I’ve used in this line of work. My mounts really have to handle with precision. Position is the key to keeping the advantage. I have always roped with a loose twine and taken my dallies. In all these years, I’ve only had one horse badly injured—a busted leg.

“I never did work for any of those huge buckaroo outfits that run a wagon and have a big crew, but I’ve always stayed with old vaquero ways over here in my home country.”

Monk and his wife Wanda now live on and run a remote high-elevation ranch that straddles the Arizona-New Mexico border. In late 2007, the rather routine act of roping a gentle range cow in a corral, on a seasoned horse, turned into a colossal wreck. Hours of evacuation—pickup to ambulance to helicopter—were excruciating. At the hospital in Las Cruces, New Mexico, doctors determined that Monk had suffered a massive heart attack, and he came close to losing a badly damaged leg.

As of this writing, the man is back at it, rawhide reins and long catch rope in hand, forking an ancient Visalia centerfire saddle that would receive an approving nod from just about any vaquero viejo.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Warner Bros. –

In roping, one can tie the rope to the saddle horn, then go and catch something. As long as the rope or the horn doesn’t break, the “something” stays caught. If the something is big and soggy, one can expect a major impact to both horse and critter when the rope comes taut.

Alternatively, one can catch something with a loose rope, then “dally welty” some rope around the saddle horn to complete the catch. (The author references this in his article as “my dallies.”) Dally welty is the rough anglicization of the Spanish dar la vuelta, which means “to give the turn.” If the horn has been wrapped with inner tube rubber, a turn or two will hold the critter. If the horn is “slick”—wrapped with leather, vaquero style—the number of turns is adjusted to the situation, with the advantage that rope can be “run” to gradually “set the brake,” thus minimizing the impact of stopping a heavy critter.

Old-time vaqueros used only hand-braided or twisted rawhide reatas (see above) with which to catch and handle stock. These “gutlines” were not nearly as strong as modern nylon or poly ropes, so they had to be handled with considerable finesse to prevent breakage.

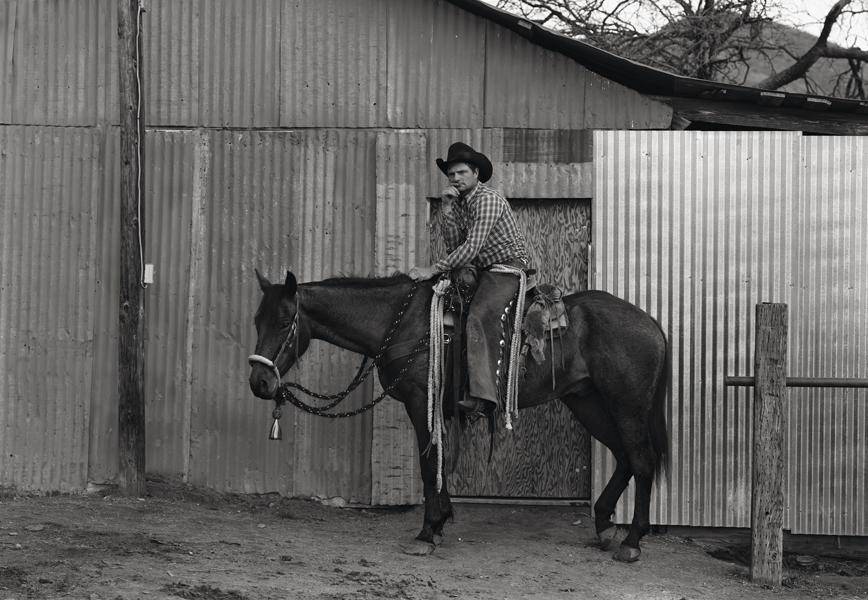

Photographed at the AY Ranch in Arizona in 1982, Monk Maxwell, on Clayton, shows the first phase, the jaquima (hackamore). It consists of a simple headstall, rawhide bosal (noseband) and mecate (twisted horsehair rein and lead rope).

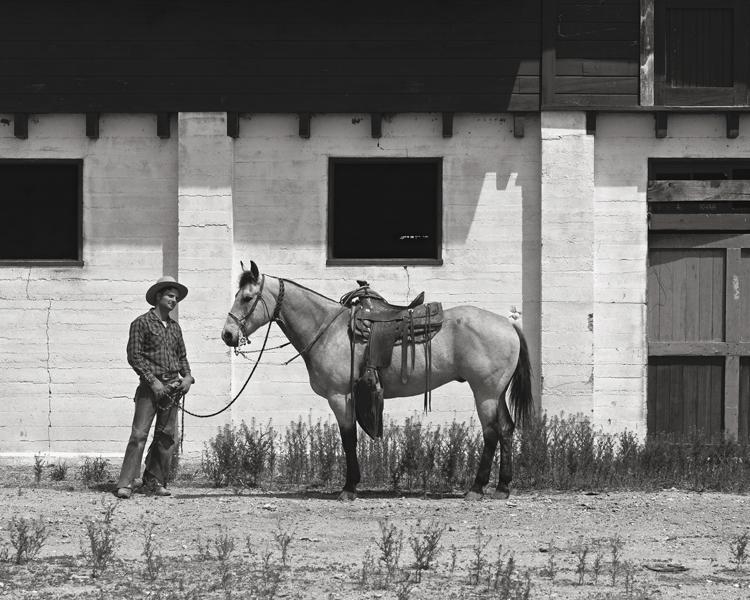

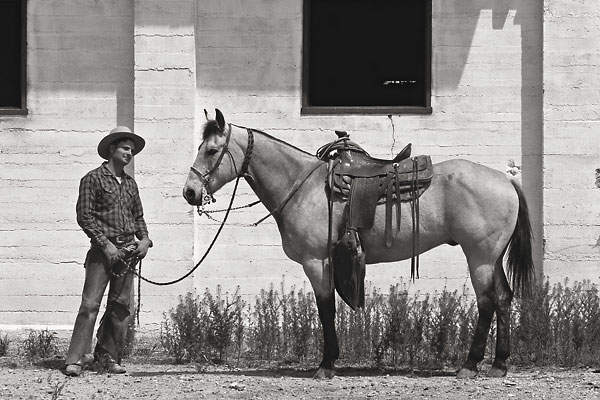

Monk with Chuckle M Dun, Del Rio Ranch, Arizona, 1970. This photo shows the third and final phase in the making of a bridle horse, “straight up in the bridle;” he’s just wearing the bit. The great California horseman Dwight Stewart was an important influence on Monk.

Monk Maxwell sits atop Chapo on the Arizona/New Mexico border in 2006, showing the second phase, the two-rein. The horse wears a lighter bosalillo, plus a bit in the mouth, with reins on both.