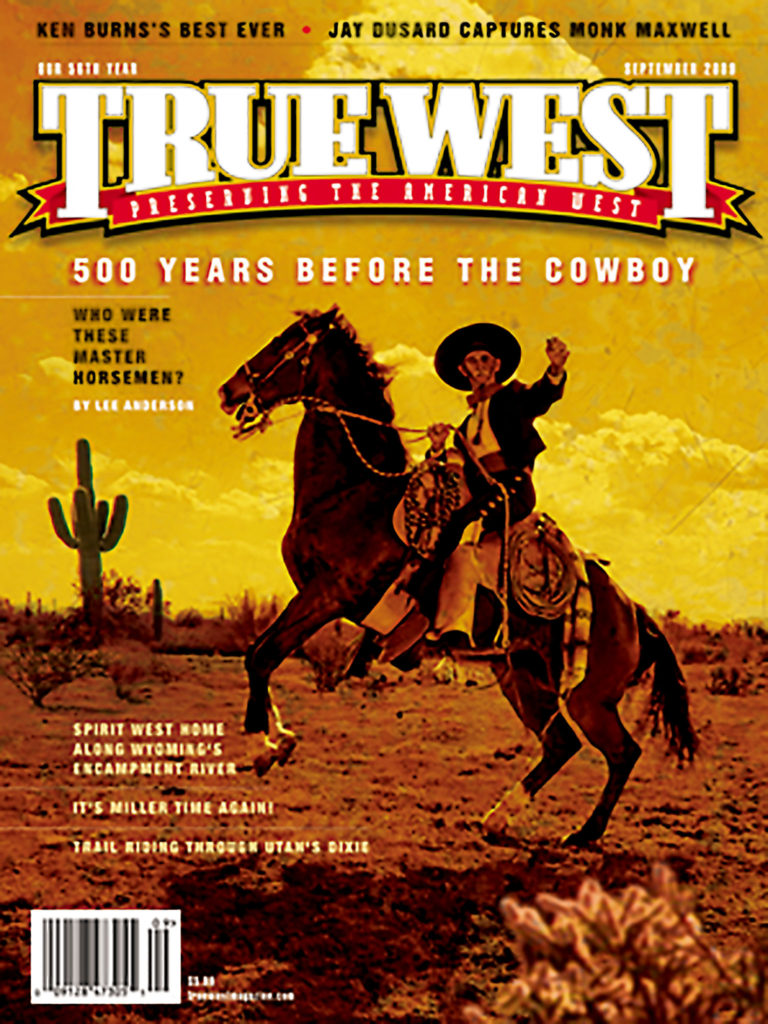

As an Old West fan you may have tried your hand at riding a horse; you might even consider yourself pretty proficient at it.

Some of you can only imagine what it must be like to sit astraddle a five-foot-tall, half a ton of living, thinking, lightning-quick muscle with nothing more than a pair of thin, narrow strips of leather attached to it for control. Whatever your level of experience, imagine what it would be like to have this animal respond to your every whim and at the lightest feather touch on the reins, regardless of how fast your horse is moving or how dynamic the maneuver you ask it to perform. This is precisely the everyday working relationship the Spanish and Mexican vaquero has had with his mount as far back as the 1700s. He was, in every sense of the phrase, a world-class horseman. The horsemanship of the average American cowboy, no offense, pales in comparison.

Conquistador Training

The roots of the Mexican vaqueros’ unique horsemanship go back a couple of centuries before the Spanish Conquistadors landed in what is now Mexico in the late 1400s. As military men, their horsemanship was the result of several centuries of battlefield-tested horsemanship in Europe. Back then, only the social elite and the military were allowed to even ride a horse. In New Spain (now Mexico), however, 50 years of cattle herds on the open range called for peon herdsmen to ride horses. The only source with the knowledge, the time and the experience to train these men was the military. The soldiers were teaching these first vaqueros the fine art of equitation and dressage 500 years ago. For the next 300 years the vaqueros adapted and perfected their dressage-based horsemanship skills to the working of huge herds of cattle. By 1800 they had elevated their horsemanship to such a science, it was truly an art form beautiful to behold.

To some degree, circumstances forced this artistry on them. Spanish horses were not large—around 800 pounds—and a full-grown Spanish bull could easily top 1,100 or 1,200. Handling one of these bulls after it was lassoed required perfect teamwork between horse and rider. The horse responded to nothing more than a shift of the vaqueros’ weight and leg pressure.

In comparison, American cowboys preferred light horse breeds, weighing from 800-1,300 pounds, using the lighter horses for pulling buggies and for pleasure riding. Unlike the vaqueros, most American cowboys did not train their horses to respond to the riders’ body language. Texas cowboys developed their own style of riding that spread throughout the American West, in which they used split reins and moved their hands to the left or right of the saddle to control the horse by neck reining.

The neck rein is the cornerstone to the partnership of the cowboy and his mount in America. The vaquero was not without his need for proper equipment. His long, braided rawhide reata (rope) was 60 to 100 feet long, while his saddle had a large diameter saddle horn. If he roped the horns of a bull, his reata was then wrapped around the saddle horn a couple of times and, being braided, stretched enough so as not to break. The vaquero then used the large saddle horn as a friction brake to “play” the bull to a stop. The horse turned its butt under the rope and leaned into the pull. If the bull was too aggressive after it was roped, the horse could be quickly sent scampering all the way around it so the rope completely encircled all four legs and the animal went down as it was pulled tight. Roping and jerking the front legs out from under it was the safest and easiest way to put a heavy or a mean animal down.

The vaquero could also throw the bull to the ground at a dead run without even lassoing it. He would reach down, grab its tail, swing his leg and stirrup leather over it, then turn his horse away at a right angle. At that speed the bull would stumble and go down temporarily stunned. Horses trained to this high level invariably carried the famous Spade Bit and were the only horses allowed to wear the alamar at a fiesta or other public function. This distinctive knot hung around the neck, at the center of the horses’ chests. At a fiesta vaqueros often fastened each rein to the bit with a single hair from their horses’ tails to then see who could perform the most impressive maneuvers without the hair breaking.

The 19th-Century Vaquero

By the 1800s the vaquero was a virtual fashion plate and a sight to behold even while working. He was so skilled at his job that he wore what would be equivalent to a modern business suit while working and roping cattle. The vaquero was flashy, preferring bright colors, silver mounted bits and spurs, and silver conchos down the length of the outer seams of his pants. If he wore knee-length pants, he’d wear decorative leather botas (boots) strapped around his lower leg. He topped off his attire with a wide-brimmed sombrero and a Mexican short jacket, because it didn’t interfere with his riding or roping (modern Levi jackets are modeled after it). He affixed his reata, when not in use, to the side of his saddle behind the cantle with the ever-present serape draped over the back of the horse, tied behind the cantle and looped through the coils of the reata. This effectively prevented the rope from flopping around when the horse was galloping.

The Spanish did not neuter animals, allowing for nearly a 100 percent calf and colt crop every year and explaining the phenomenal growth of their herds. Several early California ranches inventoried (oh, yes, they had taxes) cattle herds of anywhere from 100,000 to more than 500,000. One rancho reported 500 well-reined horses. Since vaqueros did not begin training a horse until its fourth year, the entire herd had to be 10 times that many.

In this male-dominant culture, it was beneath the dignity of a vaquero to ride any horse other than a stallion. At a rodear (roundup), one man took charge of the horses. He would stretch a rope between two stakes for the morning formado (formation). When the stallions were brought in from night grazing, he would verbally command them and they would, with impeccable manners, line up, in a specific order, with their back legs against the stretched rope. Each vaquero would select his caballo del día (horse of the day), lead it to his equipment and saddle up. The horses not chosen were then verbally turned loose for the day.

To this day, the old-time vaqueros’ everyday horse training skills have never been surpassed for their efficiency nor their sheer artistry and beauty.

Lee Anderson, of Glendale, is one of the Arizona Historical Society’s “Amazing Arizonans.” He presents living history on the vaquero for schools, nonprofits and special events.

Finding Vaqueros Today

Before the mid-1800s, media coverage and photography west of the Mississippi River was in its infancy. Therefore, we possess extremely little documentation of the Spanish culture that dominated the Western scene for some 300 years previous.

When writers and photographers were drawn into the Westward Expansion frenzy, their documents of the American West portrayed the Mexican as insignificant. How could they have realized the Mexican impact on the West when many of them could not communicate in Spanish with the vaqueros?

Movies would enhance the cowboy myth of the insignificant vaquero even further, farther and faster. For all of these reasons, misconceptions still abound about the vaquero.

In 1998, Robert Redford starred in The Horse Whisperer. His character Tom Broker is hired by Annie to heal her daughter’s horse. When they meet, she tells him, “I’ve heard you help people with horse problems.” Broker replies, “Truth is, I help horses with people problems.”

The natural horsemanship portrayed in this film may be partly responsible for the resurgence of vaquero horsemanship in America. Many traditionalists were able to revive it thanks to studious historians, such as Ed Connell, who published numerous books discussing Spanish-style equitation. You’ll find vaqueros in historical fiction, such as Tom Lea’s 1964 novel The Hands of Cantú, which shares the story of the “gifted hands of the best horsemen ever seen in New Spain.” Recent documentary films have also brought the artistry of the vaqueros to light. Corazón Vaquero: The Heart of the Cowboy (Lindeza Films) visits families of Baja California who have lived for more than 300 years on ranches without roads. J&S Productions shares the history in a five-series set, with the last of the five, “The First Vaqueros,” tracing the roots to Mexico and California. Museums also are paying attention, with the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City exhibiting 120 examples of craftsmanship and design distinctive to the vaquero in “Arte en la Charrería” from October 10, 2009 through January 3, 2010.

Those who want to practice this dying art can seek training from the author in Glendale, Arizona; Ernie Morris in Templeton, California; Richard Caldwell in Alturas, California; and Jeff Sanders in Fallon, Nevada. Some organizations preserve the heritage of Californio vaqueros, who combined the Spanish style of riding with California’s ranching lifestyle. The Californio Ranch Horse Association and the Californios are the best known, with the former hosting a fiesta competition at different locations every summer and the latter hosting a ranch roping contest in Red Bluff, California, every April.

For more than 500 years the vaquero has ruled cattle ranches, paving the way for our American cowboys. Will the art of the vaquero vanquish for good in America? Not if we can help it.