“The temperature was 122 degrees in the shade, the drinking water was 86 degrees, and the butter poured like oil. The spoiled food caused the refrigerator to stink indescribably, the meat turned green, and it was too hot to nap.”

So wrote Martha Summerhayes in the summer of 1874. She was a young Army bride, “following the guidon,” traveling with her husband, Lieutenant Jack Summerhayes by steamboat to his new duty station in Arizona.

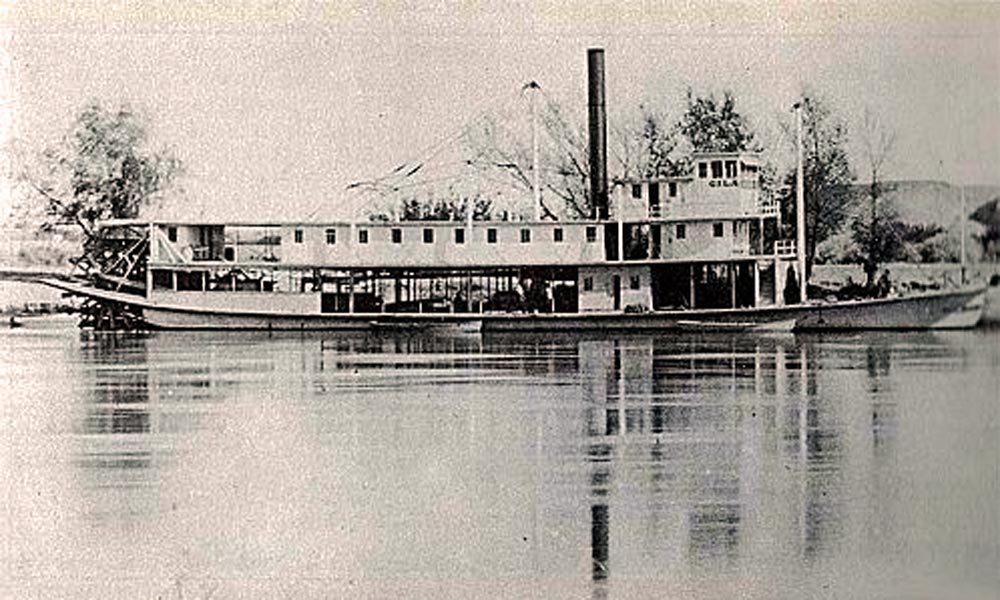

She was born Martha Dunham in 1846, and raised as a prim and proper young debutante in a prosperous and prestigious New England family. As a young woman she studied in Germany for two years and lived with the family of a high-ranking German officer. She mixed socially with the dashing militaristic Prussian officers, with their brilliant uniforms and chivalrous mannerisms. The romantic image of military life had its effect on the impressionable young lady from Nantucket. Not surprisingly, soon after her return to the States she met and fell in love with and married a young lieutenant named John Summerhayes. Soon after their marriage he was posted out West. In August of 1874 they were heading up the Colorado River in a small steamboat named the “Gila,” bound for his new duty station, Fort Apache.

In the days before the arrival of the transcontinental railroads the best way to get to Arizona was by steamboat. Ships left ports at San Francisco and traveled down around Baja California into the Sea of Cortez. At the mouth of the Colorado River they boarded steamboats and headed upstream. Their journey would include stopping at “exotic” riverport towns such as Yuma, Ehrenberg, and Hardyville.

Going up the river, the boat pulled over at night and soldiers in barges camped on shore. Since the quarters were too hot for sleeping the officers and their wives rolled mattresses out and slept on steamboat’s deck. She mentioned the decks were so hot her feet burned through her slippers, butter melted. She didn’t mention the mosquitos but old timers claimed they crossed with chicken hawks and were known to carry off small animals and children.

Arriving at Fort Yuma after several days on the river Mattie commented “Fort Yuma seemed like paradise.” She was five-months pregnant and for the first time in three weeks she was able to shower bath and eat fresh food.

As the steamboat “Gila” was plowing its way up the shallow river, Jack announced they were approaching the town of Ehrenberg, Mattie’s spirits rose. She imagined a beautiful German city on the Rhine but that quickly dissipated when she saw the desolate adobe buildings.

She wrote, “But I did not go ashore. Of all the miserable, dreary looking settlements that one could possibly imagine, that was the worst.”

The journey up the Colorado to Fort Mojave, today’s Bullhead City took eighteen days. Upon reaching Fort Mojave, the party boarded wagons and began a rigorous overland journey to the interior towns and military posts. The first was Fort Whipple, near the beautiful mountain town of Prescott. Here, the higher ranking officers of the 8th Infantry Regiment and their wives remained. Mattie would love to have remained at Fort Whipple as it reminded her of New England.

Next came the two-day march to Fort Verde where the more senior officers and their wives debarked. From Verde they began the climb up the Mogollon Rim and up on the Crook Trail to remote Fort Apache, in the heart of Indian country.

This was the duty station where the young lieutenants and their families were posted.

To get to Fort Apache Mattie rode in an Army ambulance on a narrow wagon road up and across the Mogollon Rim. The rocky trail hadn’t been designed for heavy wagons. At each steep grade the teamsters would pause long enough to figure a way to the summit. Then amidst the cracking of whips and voluminous blasts of profanity, the durable, sure-footed mules leaned into the harness and pulled the wagons to the top.

“Each mule got its share of dreadful curses,” she wrote, “I had never heard or conceived of any oaths like those….Each teamster had his own particular variety of oaths, each mule had a feminine name, and this brought the swearing down to a sort of personal basis.”

Years of Christian upbringing in a Victorian society had convinced Mattie that “at any moment the Almighty would strike the blasphemous teamsters dead.”

“The teamsters always swore,” Jack explained patiently to his bride. “They wouldn’t even stir to get up the hill, if they weren’t sworn at like that.”

Eventually, she came to understand the handling of mules, “By the time we crossed the great Mogollon mesa, I had become used to those dreadful oaths, and learned to admire their skill, persistency, and endurance shown by those rough teamsters. I actually got so far as to believe what Jack had told me about swearing being necessary, for I saw impossible feats performed by the combination.”

The young Army bride was pregnant at the time, making the trip even more uncomfortable. A few months after her arrival she gave birth to the first white child born in the region. The Apache women, curious to see a white baby, came from miles around bearing gifts.

Over the next few years she and Jack were at stationed at Fort McDowell near the Salt River Valley, and Fort Lowell, near Tucson.

Mattie Summerhayes was an eyewitness to early Arizona during those pristine days before the arrival of the railroads. She was an astute observer and wrote down many of her experiences. At the urging of family and friends, in 1908 she put these down in a book, “Vanished Arizona.”

Today her book is considered one of the best primary resources of that period of Arizona’s frontier history.

After the first edition of “Vanished Arizona” was published in 1908 she received a letter from the famous artist Fredric Remington who wrote, “I say—now suppose you had married a man who kept a drug store—see what you would have had and see what you would have missed.”

In 1911, Mattie and Jack died within two months of each other and were buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery.

“I had cast my lot with a soldier,” she wrote, “and where he was, was home to me.”