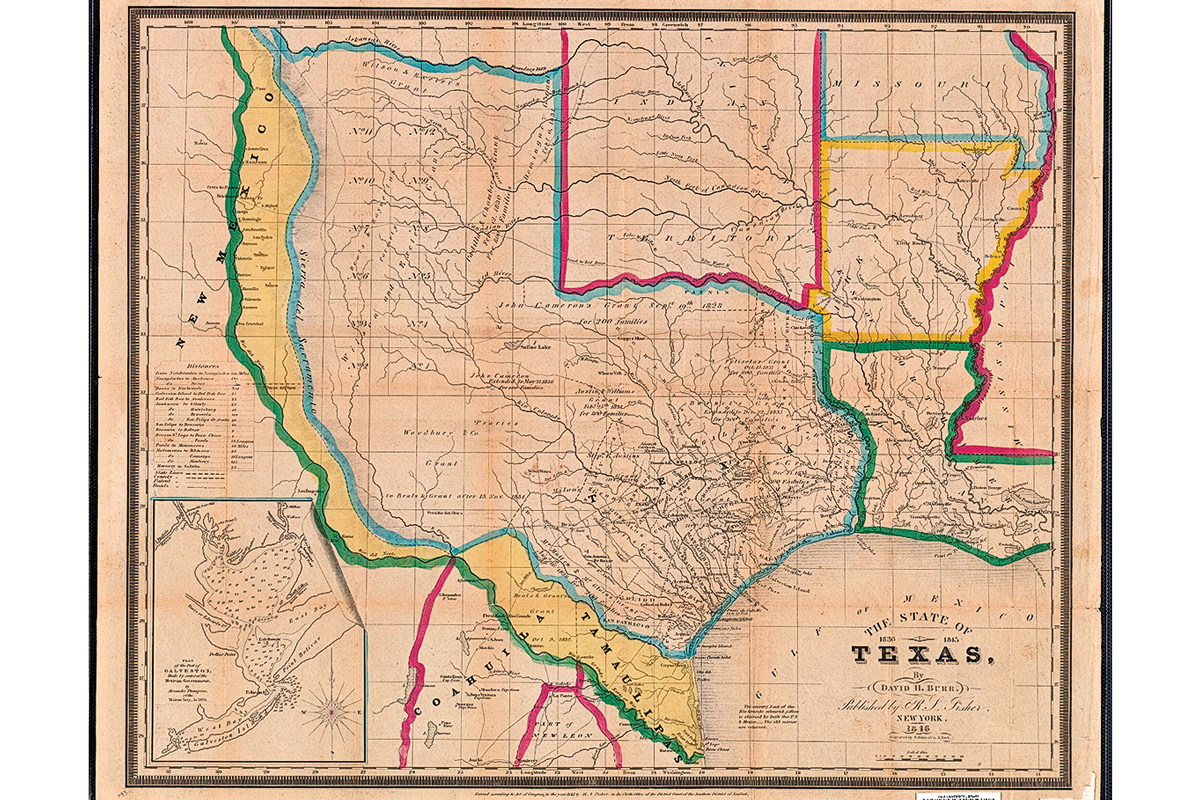

claims of the Rio Grande watershed west to New Mexico and the disputed boundaries with Mexico. The state’s boundary disputes would not be resolved until after the Mexican-American War, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo with the Republic of Mexico in 1848 and the Compromise of 1850. – Courtesy NYPL Digital Collections –

Where does the path to Texas statehood begin? There’s the Alamo, the San Antonio mission where more than 180 Texas volunteers died fighting against Mexican troops commanded by Antonio López de Santa Anna in late February and early March 1836. Or there’s Goliad, where more than 400 Texas prisoners, who had surrendered after the Battle of Coleto, were executed. Or at Gonzales, site of the October 1835 “Come and Take It” challenge, and the battle that kicked off the Texas Revolution. Or maybe it’s Washington-on-the-Brazos, where delegates drafted a constitution and declared their independence, giving birth to the Republic of Texas on March 2, 1836.

Colony, can be viewed in the Texas House of Representatives’ chamber in the state capitol building. – Courtesy the Lyda Hill Texas Collection of Photographs in Carol M. Highsmith’s America Project, Library Of Congress –

Nah, it started more than a decade earlier, in San Felipe, roughly 50 miles east of Houston. There, in 1823, Stephen F. Austin brought in 297 families from the United States to establish his colony. By the 1830s, only San Antonio rivaled Austin’s settlement commercially. San Felipe also became Texas’s first provisional capital before Washington-on-the-Brazos took over, and with Mexican troops advancing, San Felipe residents burned their town during the Runaway Scrape. Today, the town is home to San Felipe de Austin State Historic Site.

But, to kick off this journey, we’ll start 188 miles northwest in Nacogdoches, the gateway to Texas. The East Texas town was founded in 1779, but Caddo Indians had settled here in the ninth century. Just about every emigrant who came to Texas went through Nacogdoches (see the Stone Fort and Nacogdoches Sterne-Hoya museums). Thomas Rusk, who helped write the state constitution, lived here. Rusk served with Sam Houston as the first U.S. senators from the state of Texas.

No Lone Star history trip is complete without stopping in Waco at the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame & Museum. Indians had lived in the area, and a few white settlers had set up shops in the early 1840s, but it wasn’t until 1849 that George B. Erath, a Republic congressman, began laying out lots, making Waco one of the first towns founded in the state of Texas.

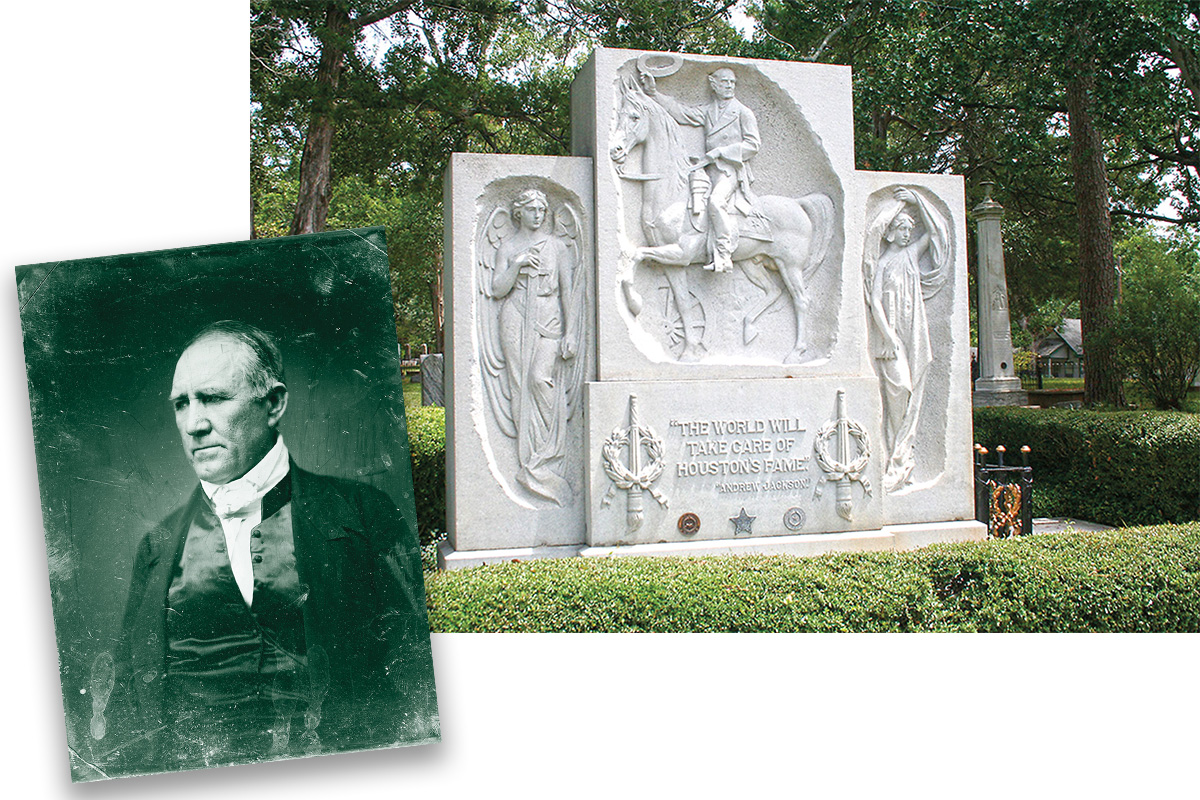

The biggest supporter of statehood, of course, was Houston. The general who crushed Santa Anna at San Jacinto in La Porte (San Jacinto Museum of History), Houston lived his final years in Huntsville (Sam Houston Memorial Museum). After winning independence from Mexico, most Texans supported annexation into the United States, but getting a treaty approved by either the U.S. or the Republic took some maneuvering. Texas, Houston said, “was more coy than forward” in its negotiations.

Mirabeau B. Lamar certainly wasn’t coy. The Republic’s president from 1838-41, Lamar and his followers figured the Republic could challenge the U.S. as North America’s big cheese. Lamar also wanted to drive all the Indians out of Texas. An adopted Cherokee, Houston was sympathetic to many Indian issues. Houston and Lamar despised one another.

Texas couldn’t get its act together. It had trouble enough finding a capital. Harrisburg, now part of Houston, and Galveston (The Bryan Museum) briefly housed the government during the 1836 fighting. The capital moved to Washington-on-the-Brazos … Galveston again … plus Velasco—which was annexed by Freeport (Freeport Historical Museum)—and then Columbia, which became West Columbia (Columbia Historical Museum), and finally Houston (The Heritage Society) from 1837-39. Austin became the capital during Lamar’s reign (Lamar serve in Houston? Get serious!). When Houston came back as president from 1841-44, the capital returned to Washington-on-the-Brazos and Houston. Austin (Bullock Museum, Texas Governor’s Mansion) finally won out with the Constitution of 1845 and statewide votes in 1850 and 1872.

San Antonio (The Alamo, Briscoe Western Art Museum) was never in the running as a capital city because it remained on the frontier. When Republic troops occupied the Alamo, they often looted the mission.

Anyone who has seen the 1952 film Lone Star knows that it took a fistfight between Clark Gable and Broderick Crawford to secure annexation. Anyone who has seen Lone Star also knows Hollywood didn’t care about actual history and never should have cast Crawford in Westerns.

It took a different kind of fight—a political one—to save annexation. Great Britain befriended Lamar and worked on getting Mexico to recognize the Republic. That worried Washington D.C., which did not want England gaining a foothold on the continent. When Houston regained the Republic’s presidency, he began working on annexation again. But bringing a slave state into the Union made Senate ratification unlikely.

Discussion resumed in January 1844. At Houston’s insistence, U.S. President John Tyler sent the Navy to the Gulf of Mexico and troops to the U.S.-Texas border. On April 11, 1844, the U.S. and Republic signed a treaty. Texas would enter the Union as a territory; the U.S. would assume $10 million of Texas debt and negotiate a boundary with Mexico. Not so fast, said the Senate, voting down the treaty, 35-16, mostly on anti-slavery grounds.

It took the lure of the West—Manifest Destiny—to make Texas a state. James K. Polk was elected U.S. president in 1844, partly on a platform of westward expansion. He wanted Oregon and Texas as states.

State History Museum in Austin, Texas. – Photo of the Bullock Museum Courtesy the Lyda Hill Texas Collection of Photographs in Carol M. Highsmith’s America Project, Library Of Congress –

“[Y]ou will perceive that Texas is presented to the union as a bride adorned for her espousal,” Houston said. “But if, now so confident of the union, she should be rejected, her mortification would be indescribable. She has sought the United States, and this is the third time she has consented. Were she now to be spurned it would forever terminate expectation on her part, and it would then not only be left for the United States to expect that she would seek some other friend, but all Christendom would justify her course dictated by necessity and sanctioned by wisdom.”

And Houston trashed Lamar’s writing?!

Mexico, pressured by England, offered a treaty with Texas, but that ship had sailed. Back at Washington-on-the-Brazos in 1845, Republic president Anson Jones called for a state constitution to be drafted. Meanwhile, the U.S. approved a joint resolution—no treaty this time—that would bring Texas into the Union.

On December 29, 1845, Congress accepted Texas’s constitution and the Lone Star State became the 28th star on Old Glory.

Jones was soon out of a job, concluding in his farewell address: “The Republic of Texas is no more.” James Pinckney Henderson took the guv’s office on February 19, 1846.

All of which started the Mexican-American War. But that’s another Renegade Road.