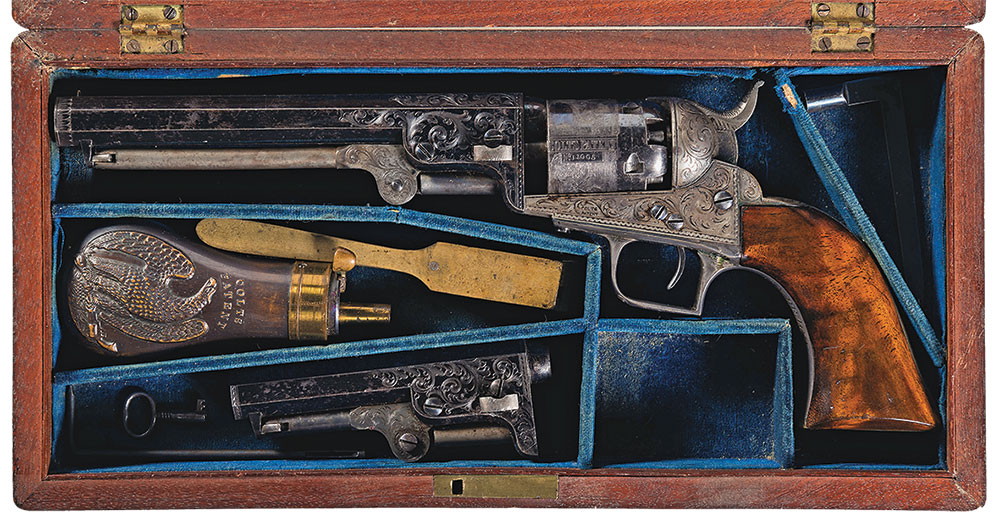

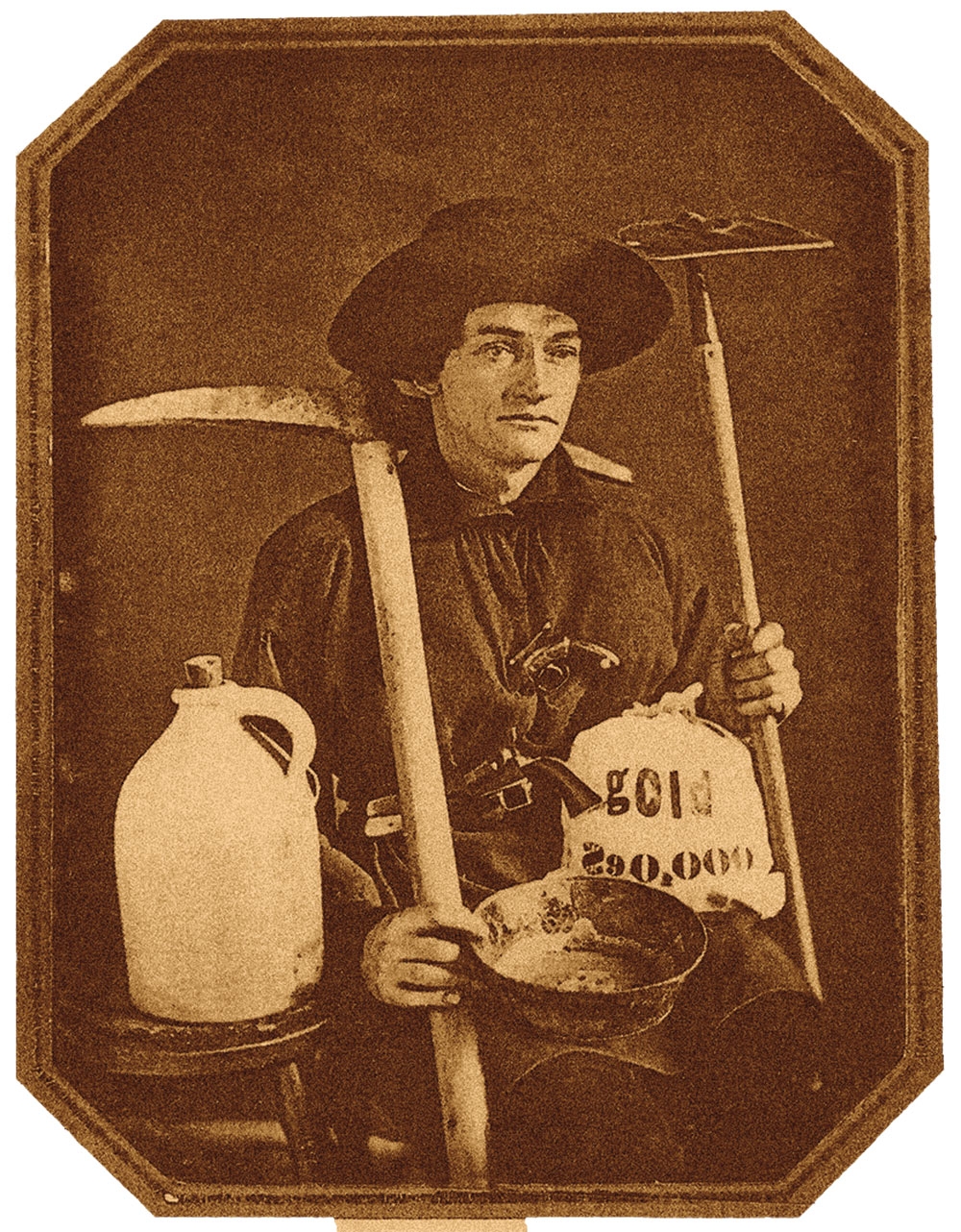

– All Images Courtesy Rock Island Auction Company –

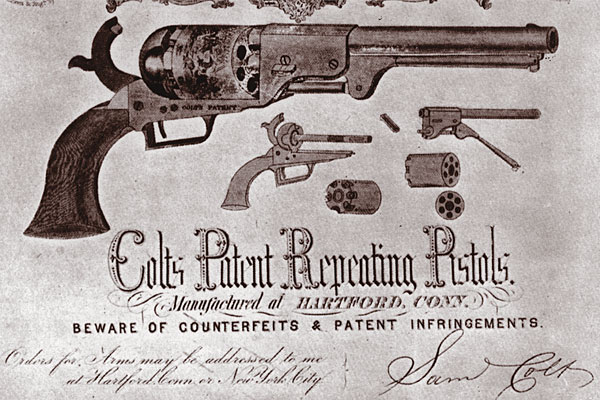

If anything could be said of Col. Samuel Colt, it is that he was an extremely astute businessman. While producing the behemoth 1847 Walker Colt and Dragoons, he recognized that not everyone needed such a huge handgun. He also knew that for the general public to be interested, a self-defense weapon must not only be smaller, but also affordable. In figuring the problems of producing a quality, reliable handgun, yet one that the average man could afford, Colt carefully studied each step required in turning out his big and heavy military revolvers. He determined that certain features deemed necessary in a large belt revolver could be dispensed with in a smaller pocket-type pistol, thus reducing the time and labor involved in the production of such an arm. According to the research volume, Colt’s Variations Of The Old Model Pocket Pistol, 1848 to 1872, by P.L. Shumaker, it has been estimated that Colonel Colt eliminated about 85 of the roughly 480 separate operations required to produce one of his belt pistols like the .44 caliber Dragoons.

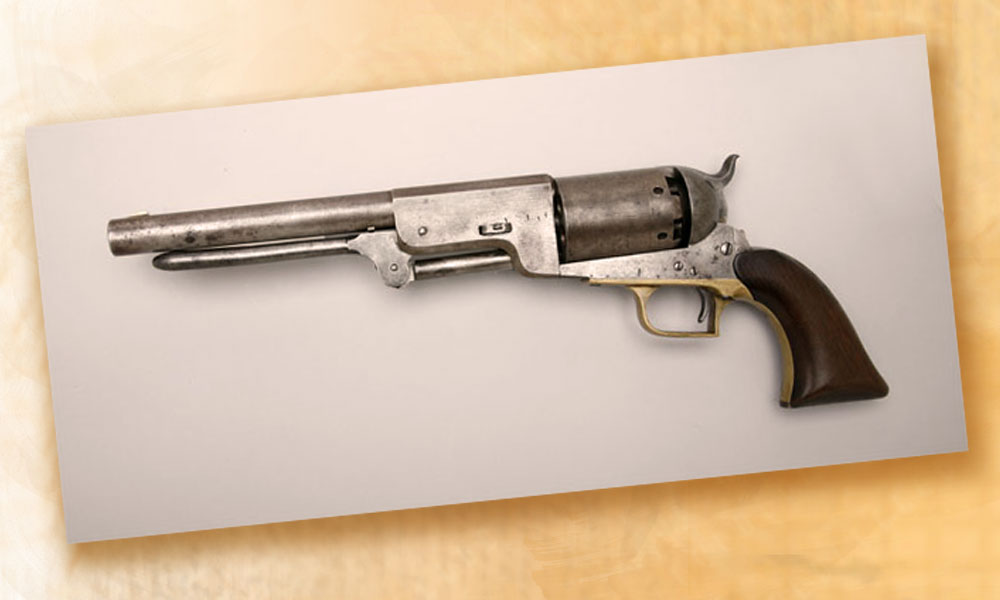

Production of Colt’s first pocket revolver started in 1847, and is what collectors now refer to as the Model 1848 “Baby Dragoon” revolver. Superior to any of the single-shot handguns then available, about 15,000 of these five-shot .31 caliber revolvers were produced in octagonal barrel lengths of three, four, five and six inches. These were made with a distinctive Dragoon-style, squareback trigger guard, and fitted with one-piece varnished walnut stocks, grip straps of silver plated brass, a blued barrel and cylinder, and a color case hardened frame hammer and lever (on later production guns). Around an estimated 150 pocket ’48 Colts were produced before the company started refining and improving them with mechanical and cosmetic changes.

As production continued, somewhere around serial number 11600 other changes took place, like attached loading levers becoming standard fare. Later models went from circular cylinder stops to rectangular in shape, and the frame was also slightly lengthened. Early ’48s wore a cylinder scene of a portion of the Ranger and Indian fight depicted, while guns made after around serial number 10500 to 11000 bear the stagecoach holdup motif, as found on the ’49 Colt.

Since early 1848s were seldom fitted with loading levers, loading one involved first knocking out the barrel wedge, then removing the barrel and cylinder. Next, each chamber of the cylinder was charged with powder, then a lead projectile (a round ball or conical bullet) was forced into each chamber by using the cupped arbor (cylinder pin) as a rammer. After this, percussion caps were fitted over the cones (nipples). The cylinder and barrel assembly was replaced and fastened with the barrel wedge. Finally, the cylinder was rotated so the hammer rested over a single cylinder “safety” pin at the cylinder’s rear facing, between two of the chambers. Because of the lack of a cutout area for capping, if a cap failed to ignite, the pistol had to be dismantled to replace the faulty cap.

– True West Archives –

Despite these drawbacks, Colt’s new pocket revolver was superior in design, function and quality, to other pocket pistols on the market at the time. The public’s approval was overwhelming. This new little “revolving pistol” was an immediate success. Again responding to public opinion, the 1848 Baby Dragoon successfully paved the way for its successor, the 1849 Pocket Model, Colt’s best-selling revolver of the 19th century. Today, with original 1848 Colts fetching premium prices, a shootable, later production replica of this classic and rare “five shooter” can be obtained from Cimarron Firearms (Cimarron-Firearms.com), proof positive that this classic pocket pistol lives on.

Phil Spangenberger has written for Guns & Ammo, appears on the History Channel and other documentary networks, produces Wild West shows, is a Hollywood gun coach and character actor, and is True West’s Firearms Editor.