It’s possible that Doc Holliday never made a house call, yet there are few Americans who don’t know him.

It’s possible that Doc Holliday never made a house call, yet there are few Americans who don’t know him.

In fact, it’s doubtful that anyone since the 1920s has entirely missed a Hollywood attempt—21 in all—at telling his story. And, though Holliday is generally cast in a secondary role to Wyatt Earp, he invariably winds up stealing the show.

In a recent interview, Harry Carey, Jr. wondered: “Why didn’t Dad play Doc the way he really was?” The answer lies in the on-going dilemma that nobody knows who Doc Holliday “really was.”

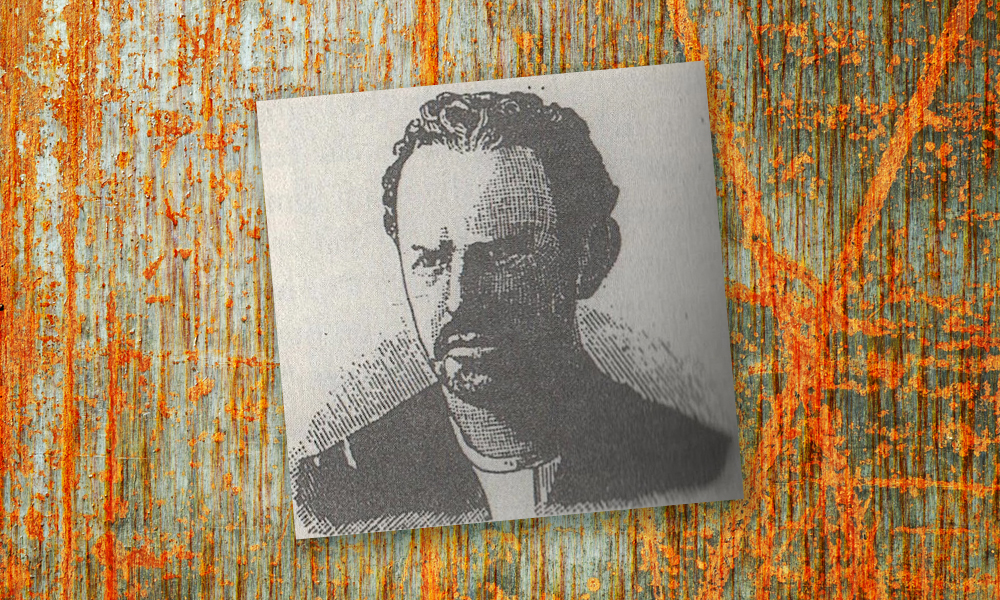

What is there about John H. Holliday, Southern gambler and educated rogue, that draws authors, scriptwriters and producers back to look at him anew? Few facts are known of his life and personal interviews were limited. Recorded comments about Holliday were generally made by men who disliked him. Wyatt Earp, his closest friend, called him a gentleman, a philosopher and a wit. Yet his words became increasingly ignored by a horde of quasi-historians, many of whom chose to emphasize the less complimentary aspects of what Earp and others had said of Doc Holliday. Bat Masterson, who knew Doc, but vied with Holliday for Earp’s friendship, termed him, “of mean disposition, ungovernable temper, and a most dangerous man.”

He was vilified by others for an “irascible disposition,” and being “the coldest-blooded killer in Tombstone.” These would become the sources generally employed for his many film appearances. Additionally, few would-be biographers failed to note Wyatt’s further words about Doc: “Perhaps Doc’s strong, outstanding peculiarity was the enormous amount of whiskey he could punish: two to three quarts of liquor a day.”

Although appearing in Artcraft Pictures’ Wild Bill Hickok in 1923, it would be W.R. Burnett’s novel, Saint Johnson, that Edward L. Cahn chose for Doc’s unquestioned major film debut in the 1932 Law and Order. John Huston’s first screenwriting attempt cast seasoned western actor Harry Carey in the Holliday role.

Kindred ties are cemented with the Earp (Johnson) brothers in an early fireside scene evoking remarkable harmony, and there is absolutely no doubt that Holliday is a professional gambler. Doc (Brandt White) appears permanently attached to a shotgun with which he eats, sleeps, and ultimately dies. Despite such verbal threats as, “The only way to clean up this town [is] let me at ’em,” the 1932 Doc Holliday character may seem to modern audiences to be somewhat of a buffoon. He dresses shabbily with the exception of a silk top hat, while the classic Holliday education is lost in the salty western dialect of the day. Any hint at a proper upbringing is lost when Holliday throws his dirty wash water out the window. Doc’s penchant for drinking sangria (with pinky extended) probably produces shudders in his loyal fans today. As with most of his first 20 years in film, Doc dies prior to the famous gunfight and shows remarkably good health throughout, fortified by unswerving loyalty to the brothers.

Law and Order introduces a romantic element with a photograph of a blonde beauty, inscribed “with love, Lotta.” Undoubtedly, this refers to the oft repeated, but never proved, Texas affair between Holliday and Lottie Deno, the lady gambler. [See the November/December “Last Stand” for what she really thought of him.]

Despite Jon Tuska’s condemnation of Law and Order as “a concentrated glimpse of human brutality,” if for no other reason than as a pace-setter, Law and Order is a classic Doc Holliday film.

Lack of knowledge failed to deter creation of the Doc Holliday legend. While until her death, Josephine Sarah Marcus Earp practically threw her prostrate body, as it were, across any cinematic effort at using her husband’s name, no one came forward to protect Doc from scriptwriters. Eight additional films in the thirties perpetuated much of the dark moodiness that would haunt the Holliday stereotype.

Frontier Marshal (a 1934 George O’Brien budget Western) starred Alan Edwards as “Doc Warren.” Harvey Clark’s Doc is an overweight, dirty and obviously drunken character in Universal’s 1937 Law for Tombstone which is basically a Texas Ranger tale in which Doc is identified following a few clandestine remarks with the hero. Doc made a shadowy appearance that same year in Johnny Mack Brown’s Wild West Days, and shows up as a surprisingly young Doc with Wild Bill Elliott in Early Arizona, Columbia, 1938. George O’Brien’s second Tombstone effort, The Marshal of Mesa City (1939), presents yet another ineffectual Holliday, but it strengthens the loyalty theme. Dressed in black, the again young and slim Duke Allison (Henry Brandon as this version of Doc Holliday) carries the inevitable ivory-handled revolvers. Shown often at the bar, O’Brien’s Holliday never coughs, and worse, is ill at ease with women.

Holliday roles throughout the 1930s are relatively minor, with a focus on his loyalty and the gambling/drinking aspects. Doc invariably dies prior to the gunfight, except in the second O’Brien film, in which he is identified as “a known killer and notorious murderer,” condemned to die at the shoot-out.

Charles Vidor’s The Arizonian, in 1936, was by far the banner film of the decade for Doc Holliday. Tex Randolph (played by Preston Foster) is one of the few suave and debonair gamblers to be seen in the next 58 years. Wearing ivory-handled revolvers, it’s gratifying to note that Doc shows no propensity for a shotgun, yet remains a decided gambler and drinker. Blatantly credited with the single-handed and highly successful Benson Stage robbery, Tex is disliked as “having killed three men in that area alone.” Holliday’s loyalty to Clay Tallant, the Earp figure, is not questioned.

Doc appears in good health; however, there is enough historic accuracy in The Arizonian to be recognized. While this film continues to portray the death of Holliday at the O.K. Corral, dramatically shot down in a smoky haze, his parting words, “I’m taking my guns,” leave no doubt that he’s a true shootist.

Although both Earp and Holliday characters had appeared heavily fictionalized in earlier films, both appeared under their own names in Darryl F. Zanuck’s 1939 remake of Frontier Marshal starring Randolph Scott as Wyatt. Director Allen Dwan talked Josephine Earp out of a $50,000 lawsuit for the use of her husband’s name. Opening frames declare that the film is “based on a book by Stuart Lake”, but screenwriter Sam Hellman consistently misspells Doc’s surname as “Halliday.”

Eight minutes into the film, the character is declared “the coldest killer in these parts,” as Ceasar Romero turns in a surprisingly good Doc—unbelievable, but certainly likeable. He is again young and well- dressed, but they portray him as a medical doctor and definitely not from the South. Worse than the sangria, Doc drinks milk in the opening stages of Frontier Marshal and (with a sigh of relief) he returns to whiskey midway into the story. His skill with a Buntline Special is early proclaimed, and he is blessed with not one, but two lady friends. Frontier Marshal finally shows Doc in fits of tubercular coughing– a matter ignored in film to that date.

Music, of course, had not been an option for silent Westerns, but the sound track for Law and Order alleviated some tedium, upped a notch by solos and mournful laments in The Arizonian. “Departure” music became somewhat of a mainstay for several decades of O.K. Corral stories, since vaudeville, traveling theater groups and saloon girls were a must to complete the picture of 1880s life. Fortunately, unlike the stories of Billy the Kid and the Alamo, no one has yet attempted a musical O.K. Corral.

Paramount got on the bandwagon in 1942 with its release of Tombstone: The Town Too Tough to Die, but it was Howard Hughes’ 1943 The Outlaw that blew everything out of the water. Decidedly one of the most historically inaccurate of Hollywood sagas, Hughes nonetheless produced the first adult Western with a Doc Holliday character. Although the tale wanders far afield with the gambler in Lincoln County, New Mexico, cavorting with Billy the Kid and Pat Garrett, The Outlaw is a surprisingly good Doc Holliday story, with the lead played by Walter Huston. Doc’s wit blazes in homespun quotes and philosophy; his poker playing is par excellence; and his flashing twin revolvers drop two deputies in early scenes. Rio (played by the voluptuous Jane Russell) is given questionable medical advice by the good doctor as he rides off displaying a surprisingly controversial knowledge of Indian ways, tracking and staying ahead of a posse. In a final gallant gesture, Doc allows himself to be gunned down by Garrett and is placed in a grave marked “Billy the Kid” (playing to a popular theme that Billy escaped to a better life).

The real hero of Hughes’ film is the roan pony over whom Doc and Billy constantly barter. And while Jane Russell’s bosom (which was touted as Hughes’ reason for the film) gained more fame than The Outlaw, “Red,” the roan pony, turns in possibly the best performance of the show.

John Ford led the way in making Westerns a leading feature in America’s viewing preference. His 1939 Stagecoach features a drunken doctor with Southern manners (played by Thomas Mitchell) who can easily be identified as an older Doc Holliday character.

Ford continued in 1946 with the classic Tombstone story, My Darling Clementine, in which Victor Mature portrays an unusually dark and pensive Holliday. Mature’s was not an easy lot as it cast him opposite Henry Fonda in the Wyatt Earp role, and Ford plagued his performance by calling him “Liver Lips.”

Doc is, however, a qualified surgeon, educated in the classics, with a touch of mystery added by frequent trips to unknown destinations. He is declared as “owning the [town’s] gambling.” In a possible effort to whitewash his reputation, Dr. Holliday is given a good woman who shows up from the East to vie for his affections with the bad girl/good girl character played by Linda Darnell. The only shot Holliday fires in My Darling Clementine is at his own image in the mirror. His violent fits of coughing play a dramatic part in the Ford film; however, Holliday dies, once again erroneously, at the O.K. Corral.

Despite the rise of Westerns in the 1940s, the glory days of “horse operas” in every media imaginable were just around the corner in those Fabulous Fifties—the wonder years for America and the golden age of Hollywood. America felt good about her past and much of the myth of the West remained unchanged, including Doc Holliday.

Powder River (1953) kicked off Doc’s appearance on screen in the fifties, featuring Cameron Mitchell in a drama of drink and depression. Columbia’s 1954 Dawn at Socorro is strictly a romantic Holliday story in which Rory Calhoun emphasizes the gallant and dashing figure soon to be lost in more dreary portrayals. The little-known Masterson of Kansas, that same year, contains an excellent Holliday portrayal by James Griffith who looks the part and conveys the sarcastic wit for which Doc became well known.

The most popular Tombstone movie for at least 35 years however, was Leon Uris’ Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, directed by John Sturgis in 1957. Kirk Douglas is a high-strung and morose Doc Holliday, cast opposite Burt Lancaster’s almost puritan paragon of virtue, Wyatt Earp. Although Douglas’ Holliday is bad tempered and a woman abuser, he wins the audience with flashes of character. Doc’s skill with knives is a keynote in the Uris storyline, although his speed and accuracy with six-guns actually support the legend.

The Sturgis film introduces a rivalry between Doc and John Ringo, whom Doc kills at the O.K. Corral shoot-out. Doc survives the gunfight but is left alone with his cards and whiskey when Wyatt rides off to a new life in California.

By 1959 television viewers were viewing no less than 48 Westerns weekly. Doc Holliday made cameo appearances in at least 11 of these serials, played by no less than 10 different actors, including Gerald Mohr, Peter Breck, Martin Laudau and Jack Kelly. Doug Fowley’s performance as an older, surly-but-humorous Doc in The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp was among the more unique impersonations. He was later replaced in the series by Myron Healey. Two pilots for proposed Holliday series featured Adam West (ABC) and Dewey Martin (CBS), but both failed.

The 1959 film, Warlock, based on Oakley Hall’s novel, is better placed with the 1960s era. Both Holliday and Earp ( again played by Henry Fonda) are portrayed as warped personalities and a homosexual relationship is implied. Anthony Quinn as a twisted, club-footed Doc intensifies the darker side of the gambler while excessive violence, both in language and action, leaves little to the imagination.

Several factors in the sixties—John Kennedy’s assassination, anger toward the Vietnam situation and political corruption combined to produce an attitude of hero- and tradition-bashing that lasted for three decades. John Holliday did not escape this trend and his image darkened, along with national hope.

Doc Holliday made only two movie appearances in this decade: John Ford’s, Cheyenne Autumn (1964) introduces a zany, wisecracking Holliday and Earp scenario. Jimmy Stewart, who played the Earp figure, explained this portrayal as an effort “to keep the audience from going to the bathroom,” amidst a serious and newly emerging Native American awareness.

The second, John Sturges’ 1967 Hour of the Gun, is considered another of the classics. In this Mirisch production, Jason Robards, Jr., is cast as a mature, world-weary but wise Doc. Viewers probably had little difficulty believing Doc as a Civil War veteran; he is depicted in almost a father-figure role to James Garner’s Wyatt Earp. Playing Doc not as robust and edgy as others, Robards gives the best performance to date of Holliday as a man of wry wit and humor. There is, however, little doubt as to Doc’s stoic lack of humanity in Hour of the Gun.

In 1968, a Star Trek episode added a science fiction note to the Tombstone saga as Westerns on television, and in the movies, gave way to other themes. The sixties weren’t rough on Doc Holliday, although he did emerge as a conflicted, more sinister figure. The following decade would prove tougher.

The seventies were not kind to Doc, identifying him with the rebellious nature of despair and fatalism that marked the decade and proved an all-time low for Holliday in film. Pete Hamill’s antiwar/antiestablishment Doc in 1971 nearly obliterated any hope for a romantic, mythic view of Holliday. There are no holds barred as Doc (portrayed by Stacy Keach) and Kate (played by Faye Dunaway) jar the viewer with obscenities, brutality and drunken debauchery. Gratefully, thiswould not be the last portrayal of the gambling dentist on film.

Ardent antibureaucracy and a renewed interest in pseudo-psychology in the eighties nearly annihilated the Western film genre. Two made-for-television movies kept Doc alive. Wild Times (1981) included a small bit of footage with Doc (Dennis Hopper) as a drunk, slow-on-the-draw and thoroughly disreputable character. I Married Wyatt Earp, based on Glenn Boyer’s book, was released the same year and featured Marie Osmond in the title role, with Jeffrey de Munn as Doc and Bruce Boxleitner as Wyatt.

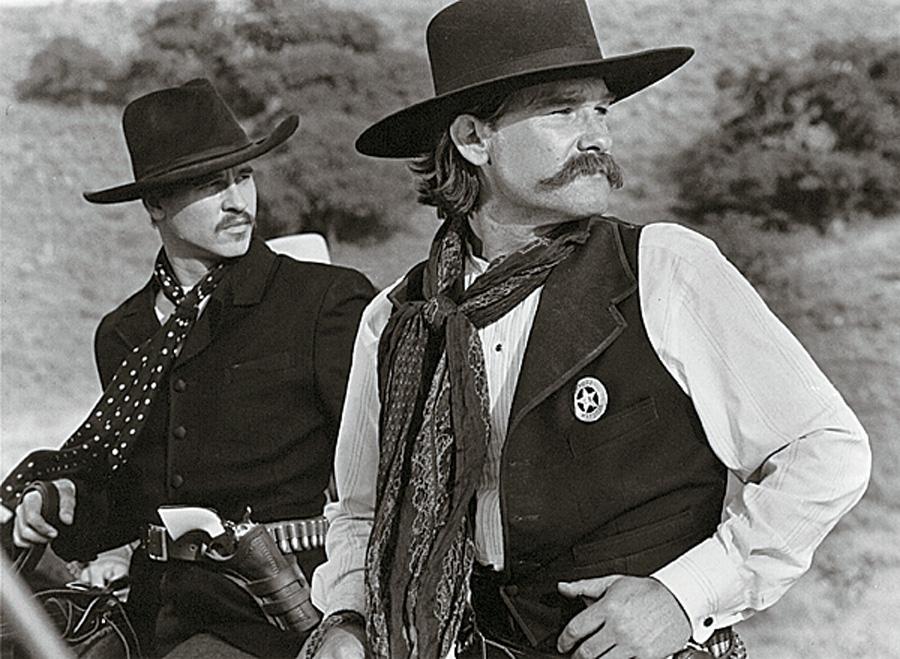

It was, of course, in the realm of film that the Tombstone story was told most eloquently in the nineties. Kevin Jarre’s Tombstone presented the most authentic telling of the Doc Holliday legend yet, and kicked off a new Tombstone fever. Val Kilmer accentuates Holliday’s deadliness with a suave, dissolute charm, while his proverbial hot temper is muted ever so slightly through a pallid sheen, bloody cough, and red-rimmed eyes. True to the code of the West, Doc knows his time is undoubtedly up when he tells Earp, “I don’t want to play [poker] anymore.” Many film critics have cited Kilmer’s character as the all-time best Hollywood Holliday, and an effort was made to have him nominated for best supporting actor that year.

Dennis Quaid, despite having lost 40 pounds for his performance in Wyatt Earp did a less-than-noble Holliday interpretation in his uncouth, profane-yet-deadly portrayal. Despite a lack of the memorable lines afforded Kilmer, Quaid did bring some life to the humorless, unsympathetic portrayal of Wyatt Earp by Kevin Costner. Some afficionados declare the perfect combination for the ultimate John Holliday would have been a Quaid portrayal with the Tombstone lines.

TNT’s made-for-television movie, Purgatory (1999), was a fanciful film in which Doc and numerous other “bad men” of the West are earth-bound in a mystic town where everyone is given a second chance at redemption. It is questionable that Doc would have wanted one.

So, I asked, Why do scriptwriters and producers continue to return to Doc Holliday? Is he any more lethal? Were his deeds of greater infamy than others? Is it the grin behind the gun, or was it that he merely, as some claim, rode into history on Wyatt Earp’s coattails?

None of these, I think. It’s the fact that the real Doc Holliday will forever remain a mystery—and the mystery itself will not let us go.