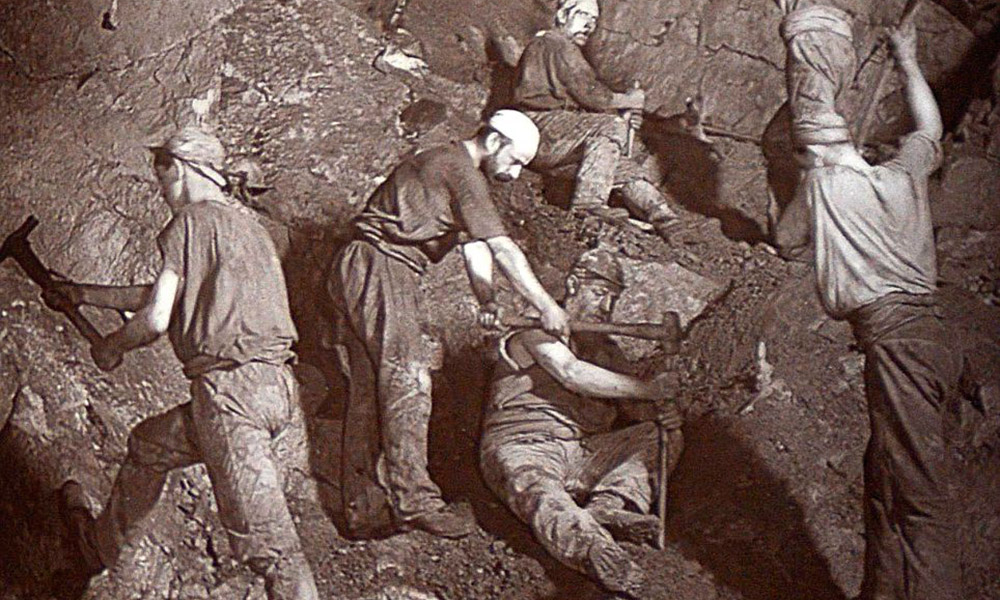

Chinese laborers played a prominent role in the construction of the Central Pacific Railroad, and they were equally instrumental in mining operations throughout the Intermountain West. Gold mining in Idaho’s Boise Basin started in 1862 upon the discoveries of prospecting parties led by D.H. Fogus, George Grimes and Moses Splawn, and miners flocked to the region. The population exploded. By 1863 four cities had sprung up: Idaho City, Centerville, Placerville and Pioneer, with a combined population of nearly 15,000.

In the early years, only a few Chinese workers were in the region, most of them finding work as cooks. People and supplies came into Boise Basin over a series of rough roads leading in from the south and the Owyhee country, as well as from the west, where they traveled by steamboat up the Columbia to jumping off points such as Wallula and Umatilla, or they came overland through the Baker Valley and along the Payette River to follow Harris Creek and then cross the divide into Boise Basin.

Gold miners took advantage of the rich lode, combing the hills and pulling significant gold from the area. By the time the Central Pacific joined with the Union Pacific in May 1869, many of the Boise Basin mining claims were already heavily worked. The railroad meant that goods could be transported by train to Winnemucca, Nevada, and then hauled overland north to Idaho City, Idaho, and other Boise Basin towns. In spite of the availability of goods, the miners had already begun to move on to new diggings. The 1870 census showed 2,158 residents in the same four cities that had populations of more than 15,000 just seven years earlier.

The population had shifted not just downward but also ethnically. By 1870 the region’s population was almost half comprised of Chinese. They moved in to the basin to take advantage of the gold still remaining, as they would work claims other miners had already abandoned. As the Idaho World, Idaho City’s newspaper, reported, by early October 1865, “between fifty and sixty Chinamen are reported to be at work on claims lately purchased by them on More’s creek, below the tollgate. This is the first gang, we believe, which has ventured into that line of business in this portion of the country.”

Many of them engaged in other opportunities: they had laundries and stores. The early laundry operations of men such as Quong Hing, Sam Lee, Hop Ching, Fan Hop and Song Lee gave way to other businesses as increasing numbers of Chinese entered the region. The Chinese merchants imported goods for market in the camps. Those who were more prosperous bought the older placer claims then put Chinese laborers to work at them. This re-working of the mines angered many “who thought the mines ought to be worked by white miners,” according to the World. But the white miners had moved on to other locations where they believed they would make more money, and the Chinese miners were satisfied with a dollar or two in profit from a day’s digging.

First Diggings in Idaho City

To reach the Boise Basin town of Idaho City, you should travel along Highway 21, north out of Boise, on a route that at one time had been in use by freighters hauling supplies to the mining camp.

A good place to begin exploring Idaho City is at the Boise Basin Historical Museum, a building that formerly served as the town’s post office. There you will get a good overview of the area’s development; on certain days you may have an opportunity to visit the Pon Yam House, built in 1865, which served as the store of one of the more prominent Chinese businessmen in Idaho City. This building is in the process of being renovated as a location to better tell the Chinese history of this area. The Idaho World newspaper office also still remains in Idaho City. It is a building first used as a Chinese store.

Idaho City is but one of the mining towns that attracted the Chinese workers in the 19th century, but few of those workers remained—not even in the cemetery. Although the pioneer graveyard had a Chinese section, when the Chinese left, they disinterred the bodies and returned them to the homeland.

Not far from Idaho City is the now sleepy little town of Placerville, which has its Henrietta Penrod Museum—housed in the former Magnolia Saloon—offering a collection of Chinese china, fans, shoes and silk items.

Headin’ North to Polly Bemis Country

Like the miners who started working gold claims in the Boise Basin, you should leave the region and travel to Cottonwood for a visit to the Monastery of St. Gertrude. This private museum has an impressive collection of Chinese artifacts from the mining era in Idaho. These include a sunbonnet, three dresses, a brown shawl, jewelry, photographs and items crocheted by one of the most famous Chinese women in the West.

Better known as Polly Bemis, Lalu Nathoy was born in China in 1853 and sold by her father as a female slave in America. Later sold for $2,500, she arrived in Warren, Idaho, where she endured a harsh life. Charlie Bemis ultimately won her in a card game with Hog King, who then owned her. The girl worked for Bemis, and the two of them later married and relocated to a small farm along the Salmon River known as the Bemis place, or more commonly Polly Place. Polly spent much of the rest of her life there. After Charlie died from burns received in a fire at their home, she remained at the farm until her latter years when she spent time in Grangeville and Cottonwood.

Each year the museum at the monastery also hosts a symposium related to the Chinese in Idaho. The event includes history presentations and often offers tours to sites important in the Chinese mining story, such as Chinese Massacre Cove in Hells Canyon (site where a gang of white men robbed and murdered 31 Chinese men in 1887). This year’s event will be held June 23 and 24.

Although not connected to the mining era, the Rhoades Emmanuel Memorial at the Monastery Museum is a stunning collection of exquisite Asian and European artifacts, with the majority of the items from China, some dating from the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

Montana’s Gold is Callin’

Gold strikes at Alder Gulch in Montana Territory drew miners from Idaho. You should head that direction too, traveling over Lolo Pass to Missoula, where you can follow I-90 to Butte and its World Museum of Mining. The museum showcases original equipment at the Orphan Girl Mine and extensive exhibits that give you a chance to see and, in some cases, handle equipment. Dozens of original and replica buildings are a part of “Hell Roaring Gulch,” including a Chinese laundry.

Even more original buildings from the mining era, and representing Chinese workers, are part of Nevada City in southwest Montana. Relocated to the area, these structures include three stores—set up with displays of tea, household goods, food, baskets and coolie hats—one laundry and other small buildings. The Chinese continued to live in both Nevada City and nearby Virginia City after the 1864 gold strikes.

Both Nevada City and Virginia City give you a chance not only to learn about the mining and cultural history of the area but also to actually experience it for yourself. You can pan for gold in Nevada City and, on weekends and some other times during the summer, you can meet “historical” characters who help bring the historic district to life. Virginia City offers visitors a melodrama, a theatrical performance or music—Country or perhaps Blues—at the Bale of Hay Saloon. Plus, you can get outfitted at Rank’s Mercantile, established in 1864, and shop at other businesses that offer 19th-century style of goods.

Just as Chinese workers who helped construct the Central Pacific Railway eventually found jobs working in

mining operations in the Boise Basin, so did those who found work on the Union Pacific find opportunity in end-of-tracks towns along that rail line. Evanston, Wyoming, last stop for the UP in Wyoming territory, had a large Chinese population.

A joss house has been rebuilt in Evanston as part of the Uinta County Museum. Within the building is a large collection of Chinese artifacts, including both an original and a replica Chinese dragon used during Chinese New Year’s parades (one is held every year in Evanston). You can also see a replica of the Chinatown, plus artifacts uncovered during archaeological excavations.

From Evanston, continue east on I-80 to reach your final stop on this trail of Chinese mining in the Intermountain West.

A Chinese Mining Riot

The first coal mining along the Union Pacific Railroad took place at Carbon, but extensive mining was soon underway in the area of Rock Springs. Like the incident that occurred at Massacre Cove along the Snake River in Idaho, an ugly racially-motivated attack took place in Rock Springs. The level of violence makes it one of the worst such situations in the history of the West.

Similar to those who had worked on the Central Pacific Railroad and later made their way to mining ventures in the Boise Basin, the Chinese who had been employed by the Union Pacific ultimately found work in the coal mines in Wyoming after 1875. That year white miners went on strike, and the Union Pacific hired 150 Chinese replacements. The Chinese workers established their own area of town and “commenced their labor … running out the coal in as good a condition as in days gone by,” reported the Laramie Daily Sentinel on November 25, 1875.

The white miners eventually settled their strike and returned to the mines.

Few problems arose during the next several years, but when another strike was threatened in 1885, sentiment against the Chinese coal miners reached fever pitch. At the time two Chinese miners were working to every one of other ethnicity. A labor riot broke out on September 2, 1885. A white mob stormed through Rock Springs’s Chinatown, killing somewhere between 28 and 52 Chinese miners, forcing others out of their homes and setting the buildings on fire.

The Chinese and their families forced out onto the desert by the rioting prompted Gov. Francis E. Warren to wire President Grover Cleveland for aid: “Mob now preventing some five-hundred Chinamen from reaching food or shelter. Sheriff of county powerless to suppress riot and asks for two companies of United States troops. I believe immediate assistance imperative to preserve life and property.”

Federal troops responded and restored order. The governor later told the Cheyenne Democratic Leader, “I have no fondness for Chinese … but I do have an interest in protecting, as far as my power lies, the lives, liberty and property of every human being in this territory … and so long as I am governor, I shall act in the spirit of that idea.”

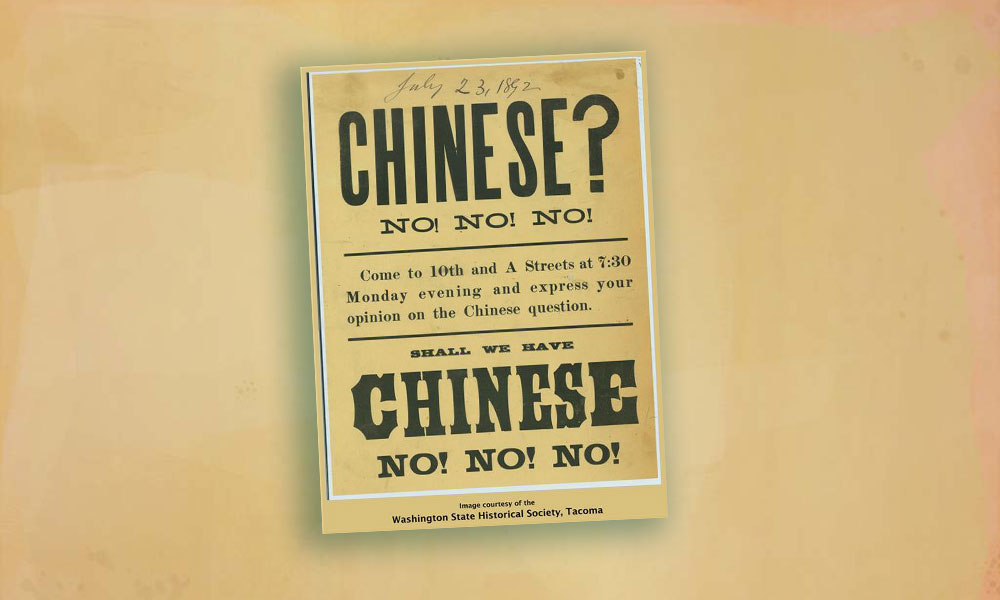

The Chinese ultimately returned to Rock Springs, but the violence in Wyoming was not unique and such incidents continued all across the West. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 certainly helped fuel the rage, as it made a point to target “Chinese employed in mining.”

In visiting these early intermountain placer camps think about the evidence of care and attention archaeologists have found in the places white miners deserted where the Chinese later toiled. Since Chinese miners characteristically employed hand labor, they did not leave dredged tailings in their wake but rather neatly piled stacks and rows of boulders that they had vigilantly hand washed. In many ways their presence, in the form of interesting, unique and sometimes priceless artifacts, is just as tenderly presented in the region’s museums.