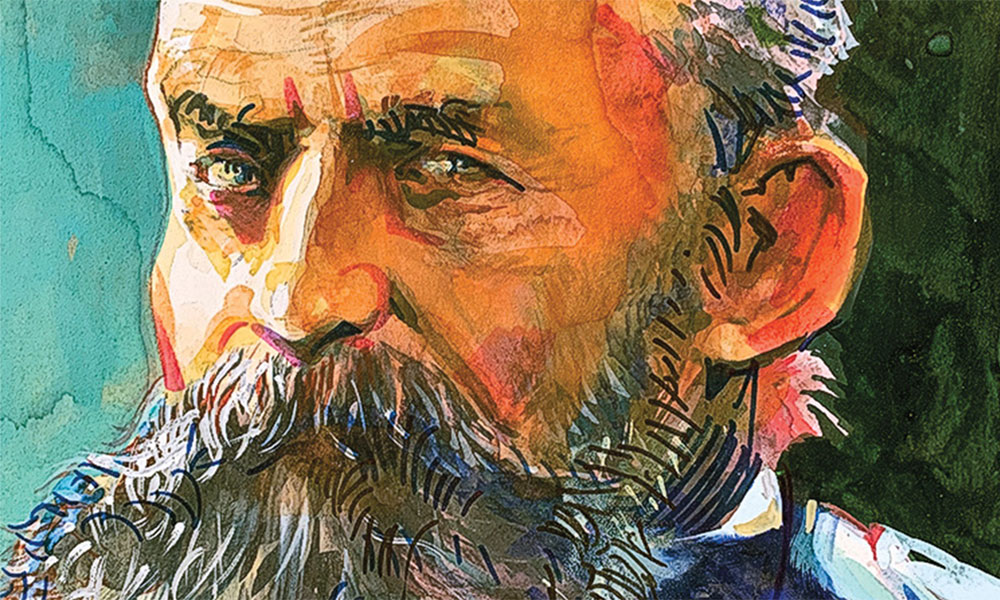

– Illustrated by James E. Taylor –

In June 1876, two battles were fought in Montana Territory between the U.S. Army and a coalition of Northern Cheyenne and Lakota warriors. Although separated by only eight days and 50 miles, the outcomes could not have been more dissimilar.

The first battle, on June 17, lasted most of the day, as the opponents were equally matched in number. The generalship on one side was novel and superb. Although one army claimed a tactical victory, it suffered a strategic defeat, one which indirectly influenced the outcome of the second conflict.

The crux of the latter fight, on June 25-26, lasted only an hour or so. It was a lopsided affair, during which roughly 1,500 combatants on one side annihilated nearly 300 on the other. The name of the losing commander became a byword for gross military incompetence.

This final encounter is a national shrine. Each year, more than 300,000 people visit the Little Bighorn Battlefield Monument outside Crow Agency in Montana. Gravestones of the fallen, both the American Indians and the 7th Cavalry, dot the field, including the one for Lt. Col. George A. Custer (the boy general’s body, though, is buried in the cemetery at West Point).

By contrast, the Rosebud Battlefield State Park is off the nearly deserted Route 314. The site offers no memorials or buildings other than a vault toilet. Only five bronze plaques, oxidized by the sunlight, stand forlornly next to a tiny kiosk containing plainly printed brochures. Nobody is around to count whoever might show up so visitation is unknown. The Battle of the Rosebud has become a mere footnote to the more glorious spectacle that occurred up the road.

A Furious Seesaw Affair

The Rosebud battle landscape is quite attractive, with a series of grassy ridges, ravines and pine forests. Birds chirrup and a gusty wind prevails as the distant chug of a tractor floats through the air. Most of the battlefield, which covers 10 square miles, is on private farmland and, therefore, off limits to visitors. You won’t find the sweeping vistas associated with the Upper Plains. Because of the ridgelines, the ability to see more than a few hundred yards in any direction is difficult. Such truncated topography explains how the day unfolded nearly 150 years ago.

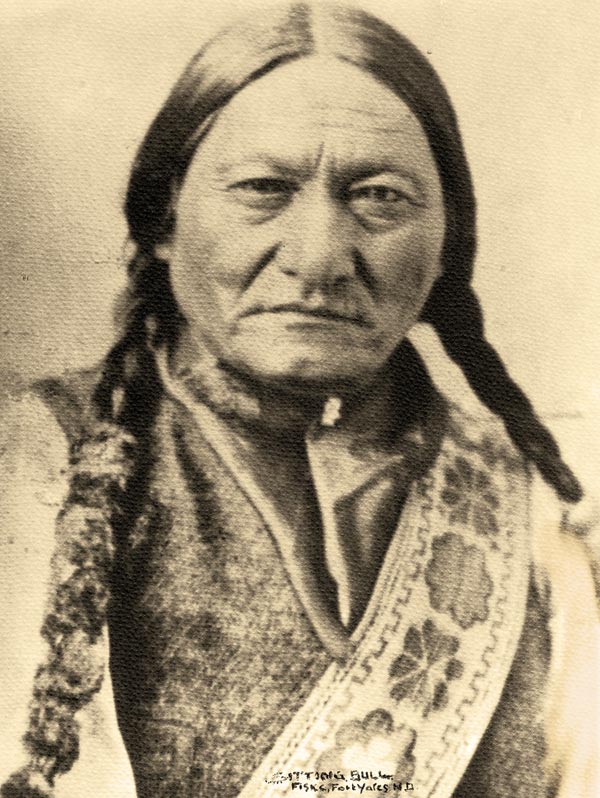

On the Rosebud battlefield, Gen. George “Three Stars” Crook advanced north to link up with Custer and Gen. John Gibbon as part of a three-pronged master plan to encircle and trap Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse’s lengthy village of Lakota Sioux who had refused confinement on a reservation.

On the morning of June 17, 1876, Crook’s troopers were shocked out of their breakfasts by Cheyenne and Lakota warriors who attacked them after a 50-mile night ride from their encampment on Ash Creek along the Little Big Horn River.

While most of the “battles” of the Plains Indian Wars were, in fact, sneak attacks, ambushes and massacres, Rosebud was a rarity; this was a pitched mêlée between two armed mounted forces, not much different than a clash of medieval knights in armor. The furious seesaw affair lasted six hours as each side used the terrain in an attempt to cut off and encircle the other. Since nobody could see who was in proximity until they galloped over the ridgeline, the Rosebud fight became a series of short-range confrontations, with gains and losses constantly shifting.

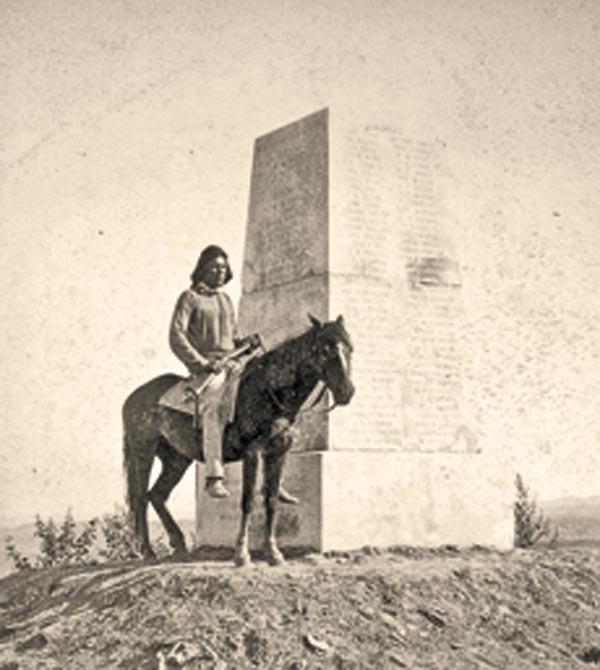

Many Old West historians have noted that Rosebud was the premier showcase of Crazy Horse’s leadership qualities. He had learned that charging off in a quest for glory and scalps would not defeat the white soldiers who were more interested in killing, than honor. Crazy Horse instructed his warriors to fight as a united force, so they could drive the invaders out of their homeland. Like any great strategist, Crazy Horse massed his forces where the soldiers were the weakest and adopted tactics that corresponded to fluid battlefield conditions. His presence that day coalesced the fighting spirit of his men…and women.

Cowardice and Courage

In the middle of the surging fight, Cheyenne Chief Comes-In-Sight had his horse shot out from under him, which left him defenseless. His sister, Buffalo Calf Road Woman, thundered in and scooped him up on her horse, thereby saving his life. A week later, she would fight alongside her husband, Black Coyote, at the Battle of the Little Big Horn. Her act of courage at Rosebud impressed the Cheyenne to grace the battle with a more lyrical title. For them, it will always be known as the “Fight Where the Girl Saved Her Brother.”

The location of her act of heroism is marked on a crudely drawn map in the state park brochure, directing visitors north to a west-facing hillock. Her rescue must have been a startling vision for the fighters of both armies. Amid the chaos and adrenaline, the deafening cacophony of eagle-bone whistles and gunshots, the whizzing of bullets and arrows, the roar of the wind through the trees came this brave deed from such an unlikely source that the Indians must have felt their blood pumping, while the cavalry troopers sensed their blood pressure soaring.

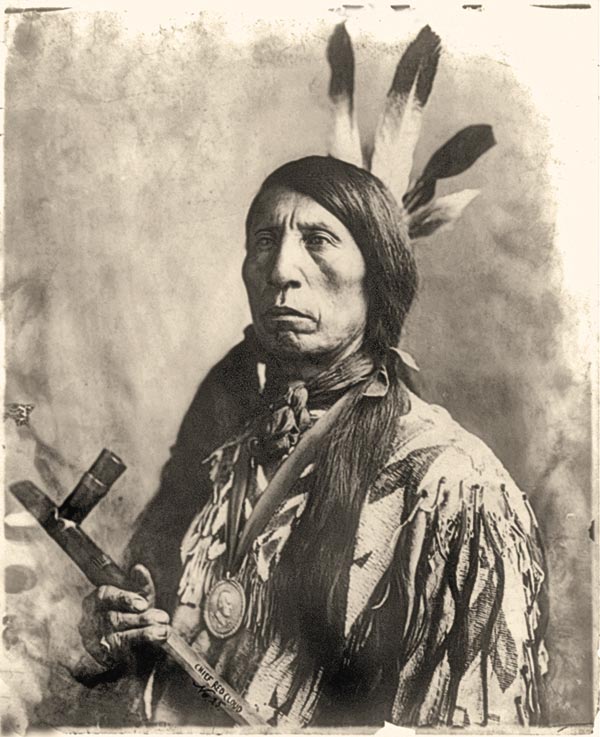

Her courageous act stood in contrast to a cowardly act committed by Jack Red Cloud, the teenaged son of the renowned Lakota chief of the same name. The youth, as yet untested in war, had prepared for battle by donning a war bonnet, a serious breach of warrior etiquette, since he had not yet earned the right to wear one. This violation was known to Indian friend and foe alike. During the fray, several of Crook’s Crow scouts surrounded the boy, grabbed away his war bonnet, whipped him with their quirts and hooted that a child had no right to be on a battlefield with men.

The pleading, weeping boy was rescued, some say by Crazy Horse, but slunk away afterwards in shame.

Terrible to Behold

From the solitary soldier’s perspective, the battle must have been a desperate affair. Overpowered by the stench of horse sweat, cordite and fear, the weather miserably hot, the troops were run down by “hideous” Indians, as 3rd Cavalry Capt. Anson Mills described: “These Indians, most hideous, everyone being painted in the most hideous colors and designs, stark naked except for moccasins and breech cloths. Their shouting and personal appearance…so hideous that it terrified our horses more than the men.”

To the embattled troopers, Crazy Horse must have been terrible to behold, with his long hair flying and his body painted in a manner alien to them. His chest and arms were covered with white hailstone totems, while a yellow-painted lightning bolt divided his face in two. This hideous demon stormed defiantly into their midst, fearless in his medicine that no bullet could harm him.

Crazy Horse’s assault was decisive enough to send “Three Stars” Crook on a reverse course back to Goose Creek, near the future site of Sheridan, Wyoming Territory. Despite the length and ferocity of the Rosebud fight, during which more than 25,000 rounds of ammunition were expended, the fatalities were fairly light. Only a total of about 40 were killed on both sides out of the 2,500 who fought there, testimony to how hard it is to hit a moving target on a galloping horse.

The ratio would be different eight days later.

Crook Versus Custer

Had Crook not been surprised at the Rosebud or had he continued on to link up with Custer, the outcome of the Little Big Horn fight might have been different. The 7th Cavalry would have been augmented by 1,000 more troops, and the overall command would have passed on to Crook, a more level-headed commander.

Not that the defeat ultimately mattered. Within a year or so, on September 5, 1877, Crazy Horse would be murdered, paving the path to extinguish all Indian resistance to white encroachment on the Northern Plains.

The bronze plaque at Rosebud notes that, in 2008, the National Park Service designated the battlefield a National Historic Landmark. Both the U.S. and the Cheyenne names for the fight are used. Yet no other visitors are on the field. Not one.

So why then does the Little Big Horn battle get all the attention? Like the Titanic disaster of 1912, the so-called “Custer’s Last Stand” was a spectacular example of hubris and arrogance. The unsinkable luxury liner. The unsinkable boy general. Both served as icons of the indestructible for their respective eras. Both lost within a few unspeakable hours. The account of the Custer calamity hit the newsstands within days of July 4, 1876, America’s Centennial. Not surprisingly, the news spoiled the party.

The Little Big Horn battle would be diminished without the colorful personality exhibited by Custer, a “flamboyant, outrageous figure” who personified the time period, as historian Evan S. Connell describes Custer. After all, few Americans know or care about the similar Fetterman Massacre of 1866.

Custer’s stature and untimely demise has left the Rosebud fight to forever remain in the popular imagination as just another battle.

Daniel A. Brown is a published magazine and essay writer, based in Taos, New Mexico, who has traveled extensively throughout the axis of the Plains Indian Wars.