The Land Run of 1891 was one of the most remarkable events in Western history.

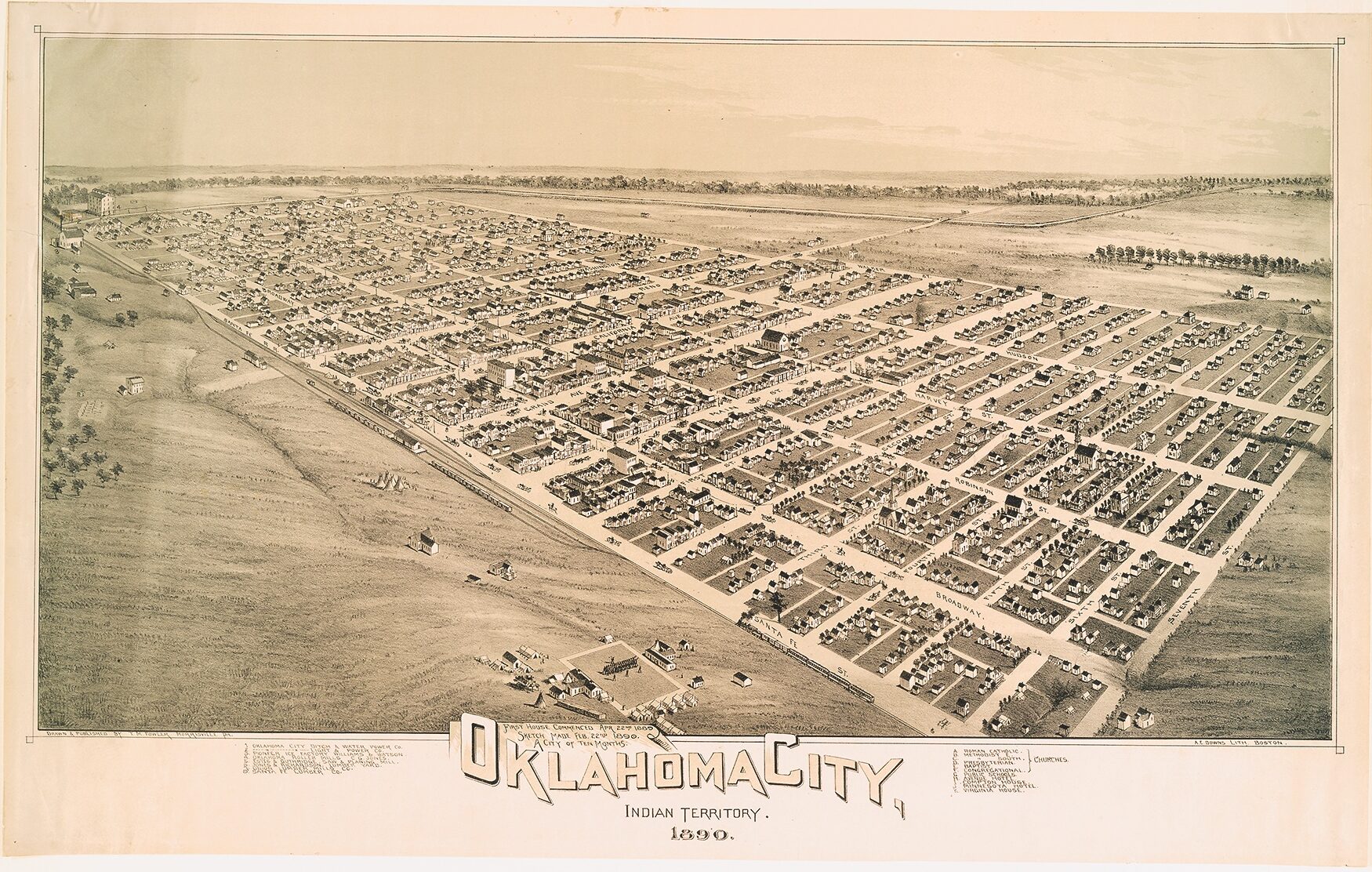

One needs to understand that Oklahoma is an instant land. There are four states younger than Oklahoma: Arizona, New Mexico, Alaska and Hawaii. But they existed in name and place long before Oklahoma was conceived in 1890.

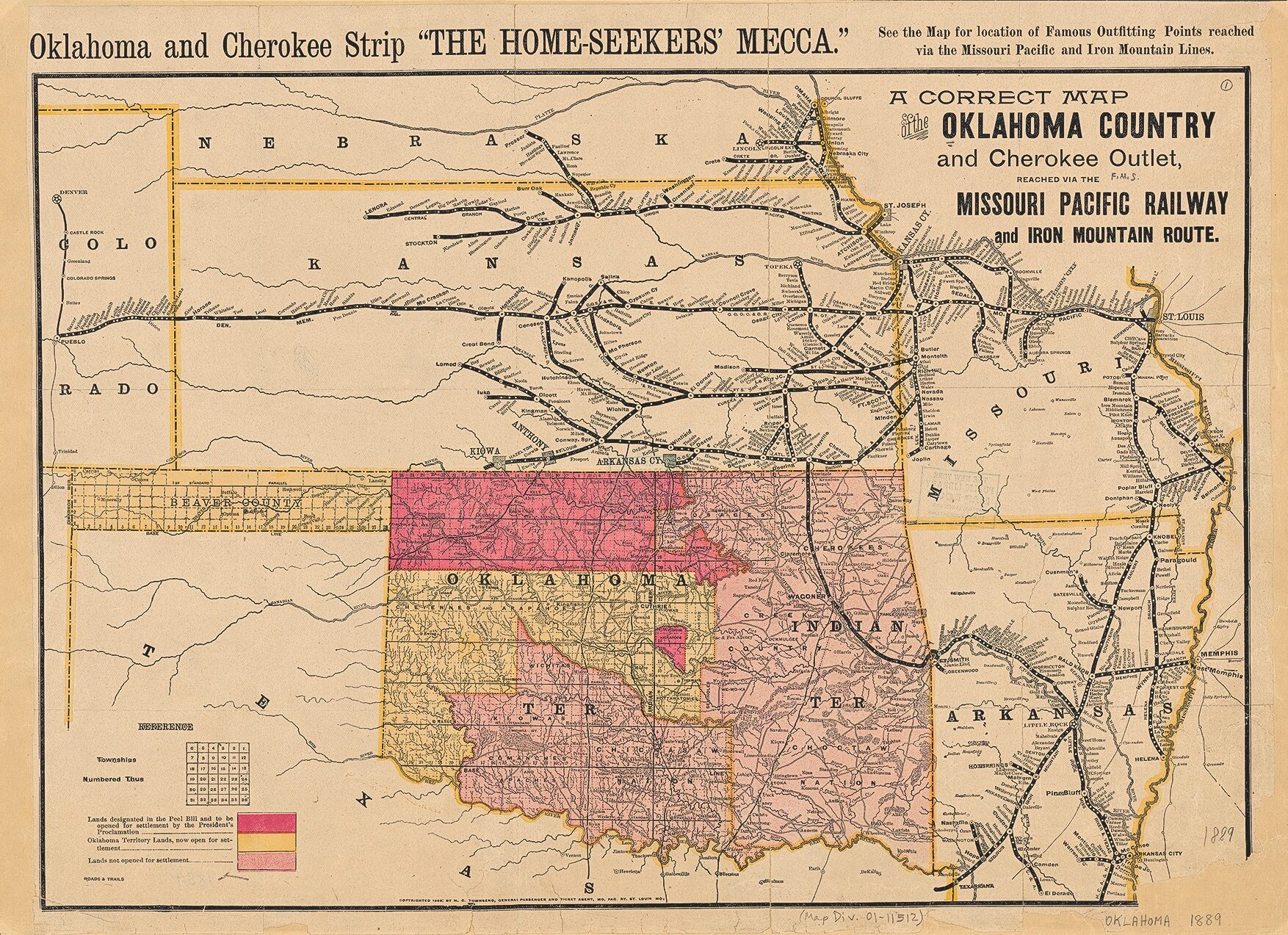

Some 20,000 people stood in the sun along a line in what would become central Oklahoma on September 22, 1891, waiting for a signal to rush in and lay claim to a farm or a town lot. More than 900,000 acres were to be opened up—6,097 homesteads, each one 160 acres—on a first-come basis.

In less than 24 hours, they would have towns built, schools established and farms marked off.

Many of the settlers had made the first land run into central Oklahoma’s Unassigned Lands in 1889, where 50,000 people had rushed in to stake their claim. Those who went early were called Sooners; among the many settlers who followed the rules were former Boomers, who had spent years promoting the settlement of the Unassigned Lands. Some had gone bust and now seemed to be given a second chance with this land run. Many of the participants were in their 40s now. As young adults, they’d sought their fortunes in Kansas or Texas or Nebraska and failed.

The sheriff of Kingfisher County in the Unassigned Lands in 1890 estimated a third of the population needed to be on relief.

The Oklahoma Territory was created from the Unassigned Lands only on May 2, 1890. The territory was to grow by adding on new lands that had been Indian reservations or in dispute with Texas. To the east, the “Five Civilized Tribes,” the Cherokee Nation, the Creek Nation, the Seminole Nation, the Choctaw Nation and the Chickasaw Nation, were designated by Congress as the new Indian Territory along with a grouping of eight exceedingly small reservations in the far northeastern corner of what later would become the state of Oklahoma.

A year earlier, the 86-member Iowa tribe sold 221,528 acres to the federal government at 28 cents an acre, keeping 80 acres for each member of the tribe. The Sac and Fox sold 391,189 acres to the government at $1.23 an acre, keeping 160 acres for each tribal member. The Citizen Band Potawatomi and the Absentee Shawnee took 1,498 allotments and 563 allotments respectively, with each allotment being 160 aces, and sold the remaining 325,000 acres to the government at 69 cents an acre.

The federal government then turned around and sold the land to those rushing in at $1.25 an acre. (The tribes later took the government agents to court—and won—on the charge of profiteering.)

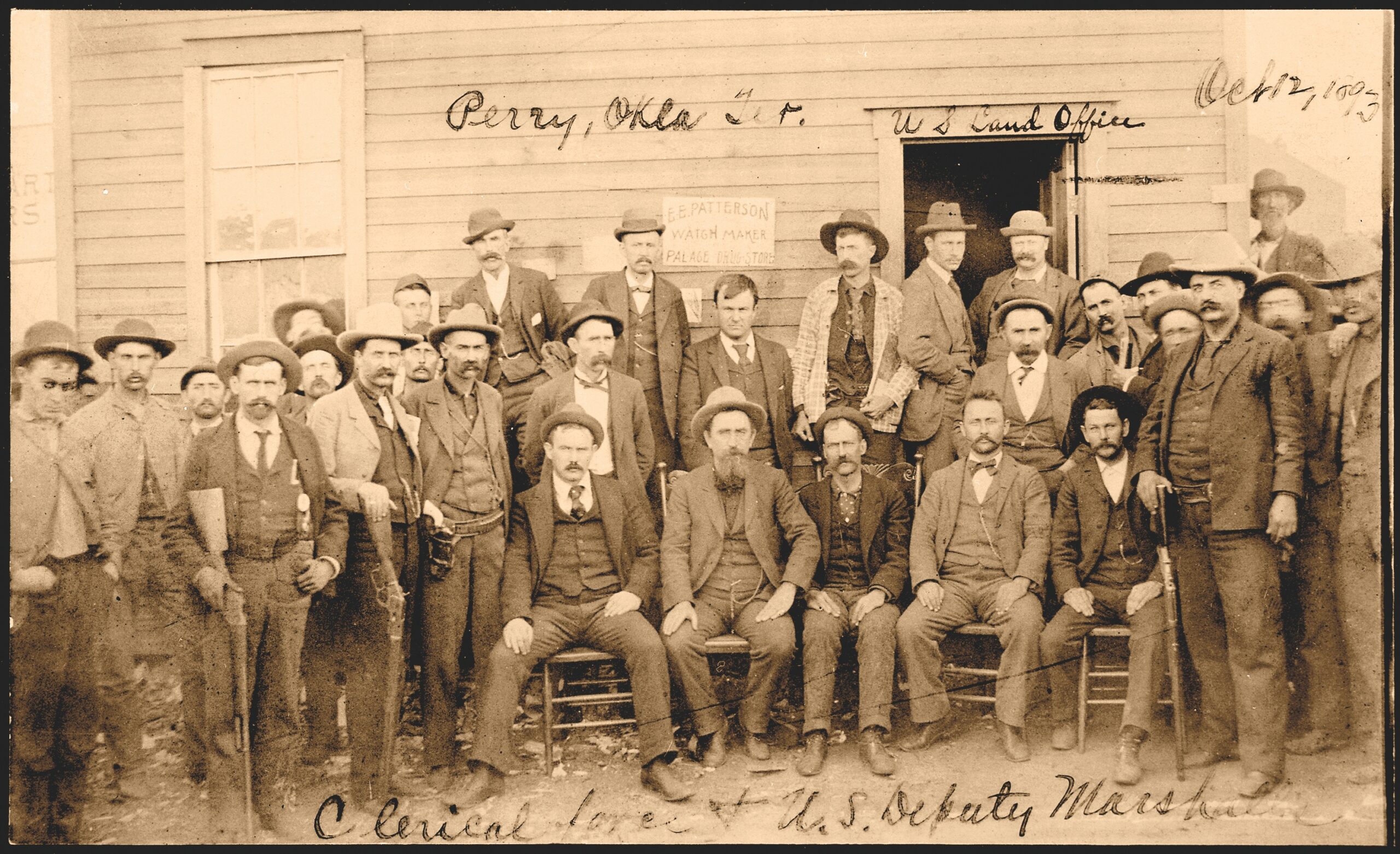

One of the items that was to be created instantly was local government. The federal government wanted to avoid the problems that arose when it awarded townsites in the Unassigned Lands during the first land run.

Those who had wanted to start businesses in the new territorial capital of Guthrie became so argumentative that four separate downtown Guthries were formed during the first month of its existence. Oklahoma City was worse. The Seminole Land Company hid would-be settlers in the woods before the land run. When the time came, they emerged from the brush—before legal homesteaders arrived—and claimed city lots for the land company. The land company had also sent in gunfighters to guard these city lots from honest homesteaders taking part in the land run. An effort was made to form a coalition government between the homesteaders and these company men in Oklahoma City, but it broke down into a massive fist fight.

To prevent this from happening again at the two county seat locations of Chandler and Tecumseh, the federal government decided lots there would be handed out at a later date after the rush had calmed down.

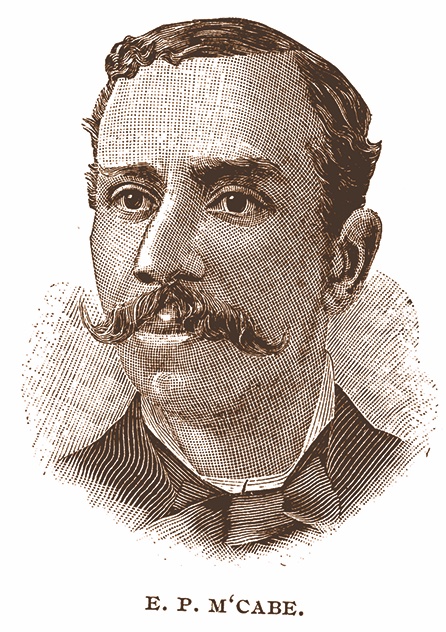

As September 22 approached, thousands gathered at Guthrie, Oklahoma City and Norman for the run. Between Guthrie and the Iowa tribal boundary was the all-Black community of Langston founded a year before.

The night of September 21, some 30 Blacks armed with Winchesters marched into the camps of the would-be homesteaders. They wanted to make it clear to the white settlers their lands were not open to the claimants. They were willing to shoot to kill if they had to. Once they felt their message was understood, the 30 left. During the land run the next day, no trouble took place regarding Langston.

Those participating in the land run were to drive their wooden stake into the land they wanted. Then they would look for a pile of rocks. Federal surveyors had surveyed and marked out allotments in a checkerboard fashion across former reservation lands. The surveyors wrote down the meridian line coordinates of the allotment sections, which served as legal descriptions for land deeds. They then piled up rocks attaching the information so settlers could find it.

After a settler staked his claim and found the closest pile of rocks to write down a legal description, the claimant had to go back to the land office in either Guthrie or Oklahoma City to file the claim, often standing in long lines for hours.

The morning of September 22, two companies of U.S. troops as well as U.S. Marshals enforced the line that settlers were not to cross until they heard the signal. Among the settlers were 1,500 African Americans concentrated around Langston for the run.

Single women were also making the run. Maggie Smith from the Guthrie area secured 160 acres, while Doskey Simmons won a claim along the Deep Fork River. Two young women from Oklahoma City stood with their toes touching the line. When the gun sounded, the women simply stepped across the line staking their claims right there.

The run into the planned county seat of Tecumseh for the future Pottawatomi County had to be delayed because the surveyors were not finished with their work. That rush began at high noon on September 23. There was only one casualty. When a Dr. Roundtree jumped off his horse to stake a town lot, he was trampled to death by the rider behind him.

The final run took place September 28 as 5,000 people sought to be first to claim one of the 2,208 town lots in the future town of Chandler, the planned county seat for Lincoln County. Among the racers was a woman, Nanitta Daisey.

The federal government had staged these runs far too late for settlers to get in a major crop to sustain themselves. Indeed, the only major crop this late in the season they could grow was turnips. Through the winter months, homesteaders in these new lands ate boiled turnips, baked turnips, mashed turnips and fried turnips three times a day. They even fed turnips to their cattle as a winter feed.

Banks were established and proved unique. Unlike other banks across the country, they had no depositors, for the homesteaders had spent most of their money for supplies to make the run. Instead, these early banks transformed into land speculation firms and dealers in horses. When they did make cash loans, the interest was at seven percent.

Surprisingly, the real economic lifesavers for these new settlers were the railroads. The railroads loaned out seed at cost to the new farmers with the loans to be paid back in wheat. The railroads also provided agricultural experts to work with the farmers planting Turkey Red wheat from Russia instead of the then traditional soft-shelled wheat. The railroads’ gamble paid off. Over 95 percent of the farmers paid their loans off to the railroads in full.

The new towns began to prosper. Chandler became the intersection of two railroads. A flour mill, a cotton gin and a brick plant opened. A cotton oil company employed 50 people. Chandler’s cattle pens were busy and fruit-packing sheds were full. Then, six years after the land run, the town was leveled by a massive tornado which killed 14 people and flattened town structures. The only building untouched was the Presbyterian Church.

There was also the problem of the whiskey towns along the new lands’ border with the Indian Territory. The Indian Territory was “dry,” alcohol prohibited, while the new Oklahoma Territory was “wet.” Saloons sprang up right along the border to satisfy the thirst of the Native Americans and the more than 100,000 whites living in the Indian Territory.

D.N. Beatty opened the first saloon, the Black Dog Saloon, a few days after the land run along the border with the Indian Territory. Soon some 62 saloons and three distilleries popped up along the territorial border as did towns like Corner, Keokuk Falls and Violet Springs, which grew up around these saloons. Shootouts between rival saloons and bartenders became common.

A stagecoach driver shouted at his passengers as he drove into Keokuk Falls, “Stop 20 minutes and see a man killed!”

“Pistols were always going off in all directions,” said bartender Bud Ellison. “It sounded like a year around Fourth of July celebration.”

These whiskey towns continued until 1907 when the Oklahoma Territory was forced to merge with the Indian Territory to enter the union as the “dry” state of Oklahoma. By then most of the would-be, hopeful farmers of the land run had become tenant farmers, as had most farmers in southern and eastern Oklahoma.

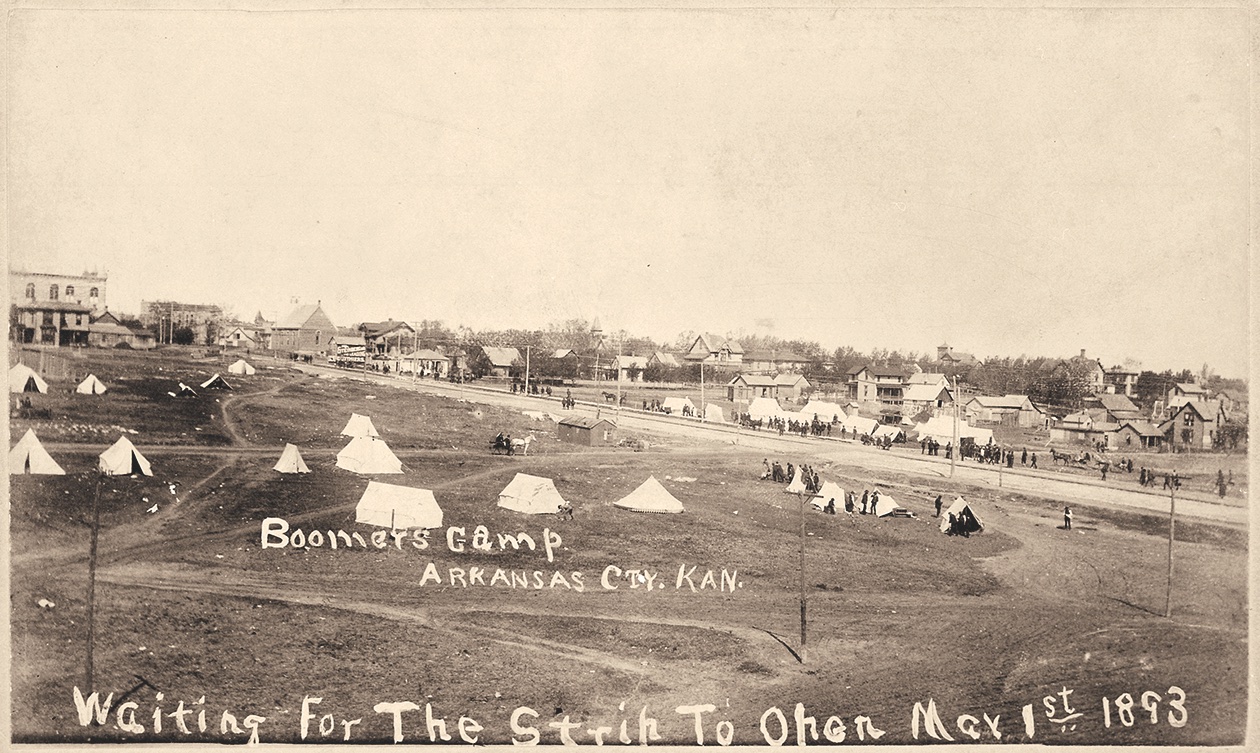

Two years after these land runs, the largest land run of them all saw 100,000 people rush onto two million acres in northwest Oklahoma to create 40,000 homesteads in 1893. Among those galloping into the Cherokee Outlet was my Great-Grandfather Ernest Buckminster who obtained a farm along Turkey Creek after brief gunplay with a rival claimant.

Mike Coppock was born and raised in Western Oklahoma and after graduating from Phillips University in Enid has lived off and on in Alaska since 1985. A former newspaper editor, he is currently historical interpreter at Denali National Park