People fought over a lot of things in the West. Precious metals. Grazing lands. Water. Even salt. Yep, that white mineral was the subject of a long-term feud southeast of El Paso near the town of San Elizario.

It started just after the Civil War. Local Hispanics—on both sides of the border—claimed traditional community rights to the salt deposits, which were used to preserve meat and more. But in 1866, the Texas Constitution allowed individuals to claim mineral rights to the area. Many of them were Anglos. The struggle was on. And it had racial/ethnic and national overtones.

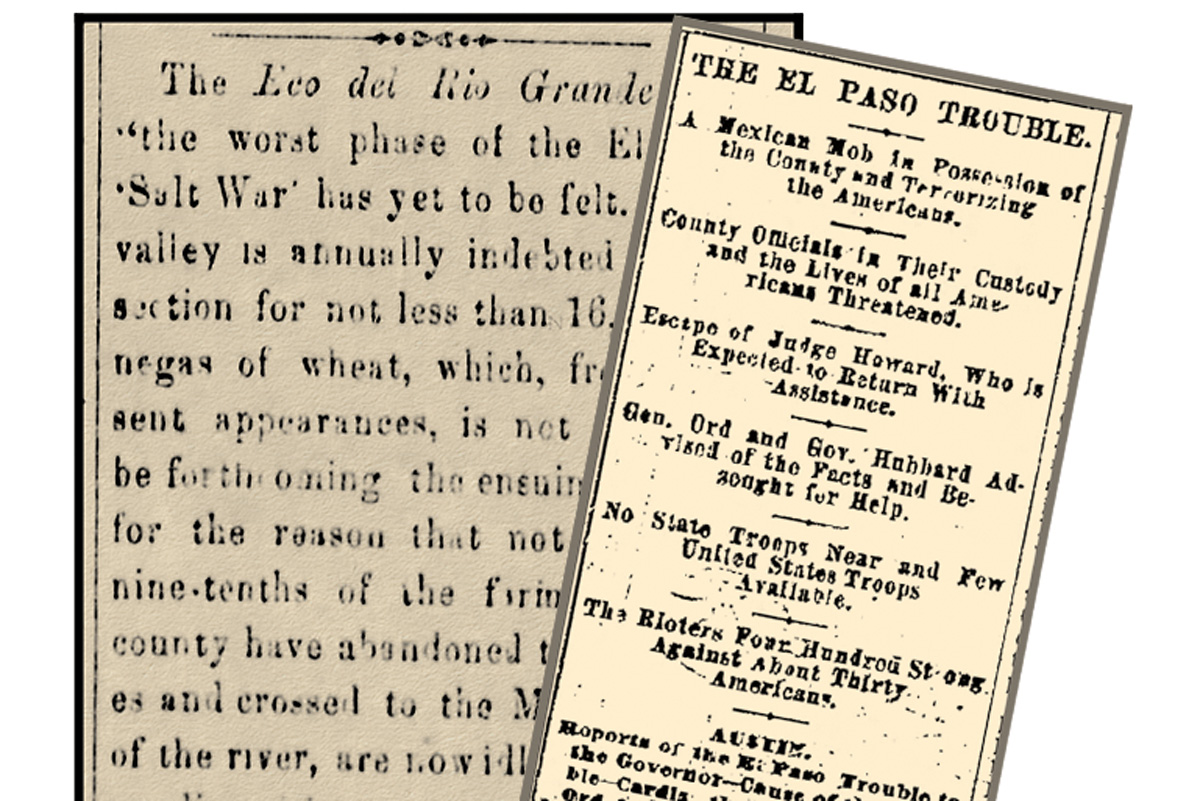

In 1877, Virginia native Charles Howard claimed the salt lakes in the name of his father-in-law. Howard was planning to charge the Hispanics for salt from his claims—and he used local Texan law officers to enforce it. But there was resistance. In October 1877, several hundred Hispanics took him hostage and held him for three days. Howard was released after he paid a $12,000 bond and relinquished his rights.

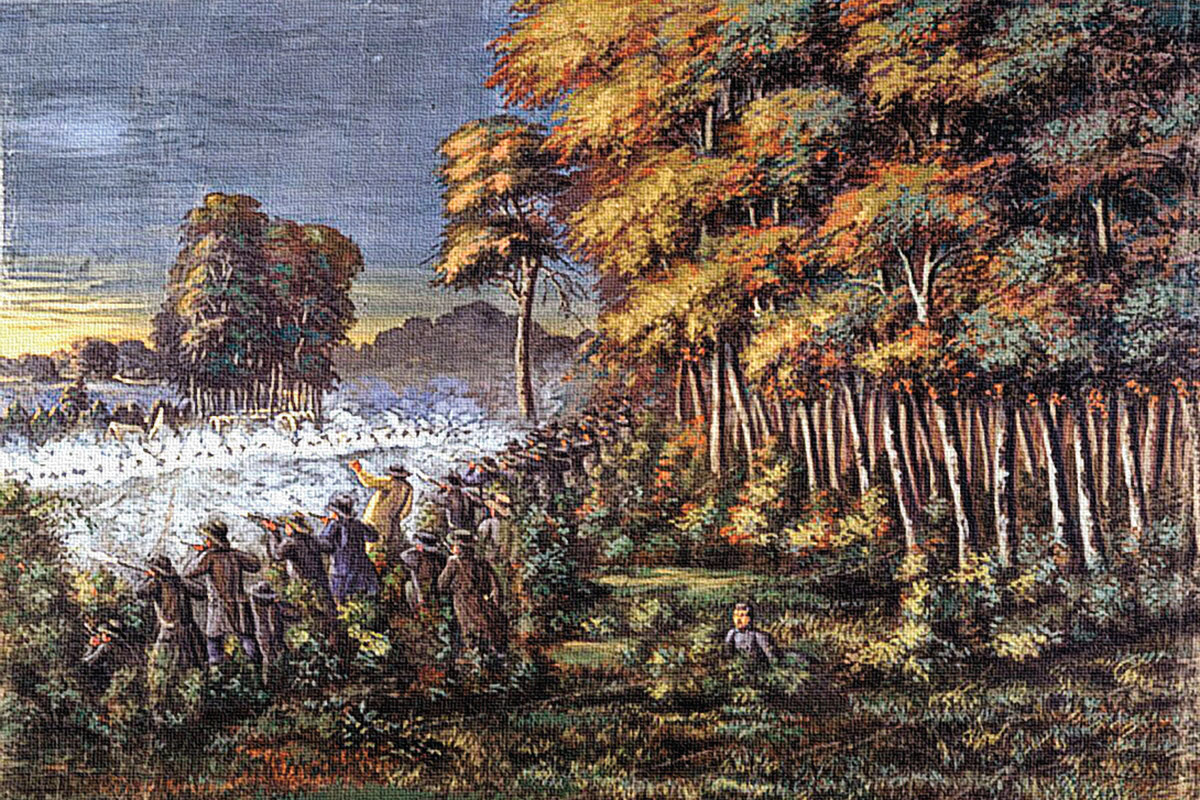

Howard left the area briefly but returned to kill one of the Hispanic leaders. Howard ran again, escaping a huge mob that was after his head. But he came back, this time on December 12, 1877. He was not alone. Lieutenant John Tays had a 20-man contingent of Texas Rangers who were charged with protecting Howard and his salt rights. They were walking into a buzz saw.

Out of the approximately 5,000 residents of the San Elizario area, only 100 were Anglos. The Hispanics controlled the region, except for local government offices, and had a vastly superior force, certainly numerically. The Ranger force was newly recruited and had little training or unit cohesion.

When Howard and the lawmen entered San Elizario, they were immediately confronted by an overwhelming force of armed Hispanics. Realizing their dilemma, the group took refuge in the town church. After a two-day siege, Tays gave up; it was the only time in Ranger history that a unit surrendered to an opposing force. The mob took Howard, Ranger Sgt. John McBride and merchant John Atkinson captive. The three were executed, their bodies hacked to bits and dumped into a well. The rest of the Rangers were disarmed and ordered out of town.

Anglo civic leaders of San Elizario crossed the border into Mexico to escape. Most never came back. Meanwhile, members of the mob looted the town and destroyed several buildings.

But it was a case of the Hispanics winning the battle and losing the war.

As a result of the unrest, the county seat was moved from San Elizario to El Paso. When the railroads came through the area in the late 1880s, they bypassed San Elizario. And a regiment of Buffalo Soldiers was brought in to nearby Fort Bliss to keep an eye on things—especially on the Hispanics.

The end result: the population of the area dwindled, and the Hispanics lost much of the power and influence they’d once had—including control of the salt deposits. The salt flats are now part of the Guadalupe Mountains National Park, pristine and striking to the eye—and belying the bloodshed that took place as groups tried to claim them as their own.