– All images True West Archives unless otherwise noted –

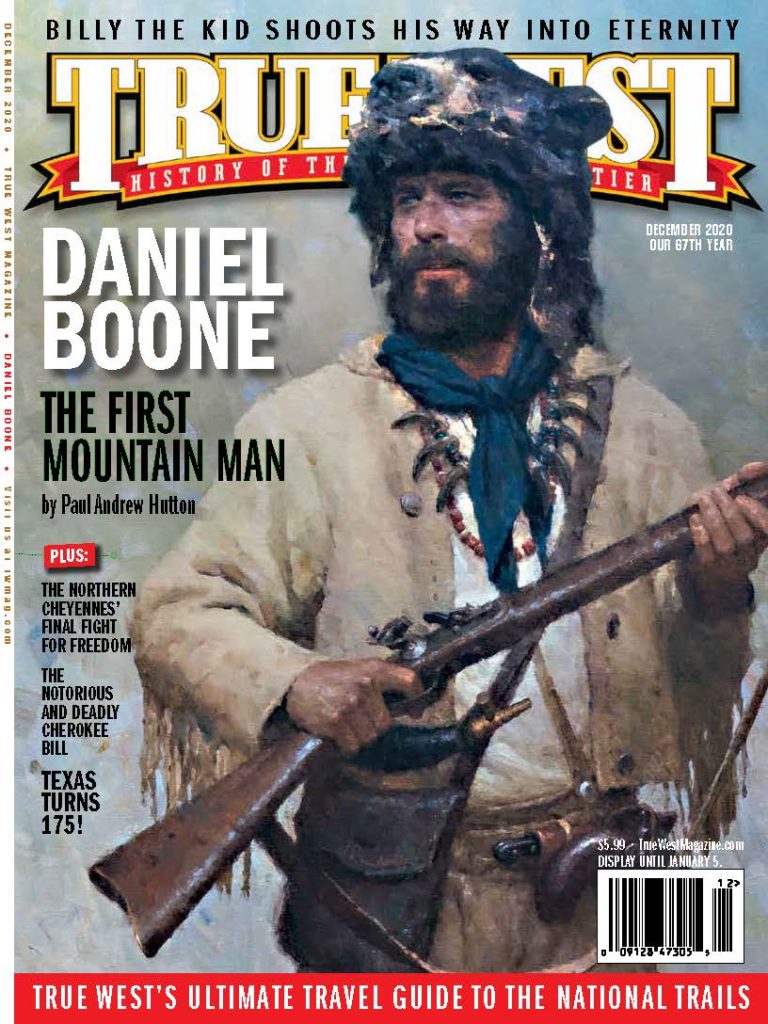

Early in the spring of 1774, a solitary figure rides westward over Kane’s Gap into Powell’s Valley, far beyond the fragile line of frontier settlements to the east. Daniel Boone, his hair plaited and clubbed up in Indian fashion, garbed in black-dyed deerskin, has come in search of the rude grave of his eldest son. James Boone and six companions had been slaughtered by Delaware, Shawnee and Cherokee Indians in October 1773 while hurrying forward with pack animals to rejoin Boone’s party of Kentucky-bound emigrants. James had called pitifully for his family in his death agony as a Cherokee called Big Jim delighted in torturing him. The massacre had momentarily ended Boone’s dream of a settlement in Kentucky.

The life of his eldest son is to be but one of a tragic string of blood payments that Daniel Boone will make to open the American West. In time he will come to be heralded as an American Moses leading his people to their Western promised land. His personal travail will be embraced by writers, artists, poets and filmmakers across the generations to create an epic that becomes the grand creation myth for the founding of a pioneer nation. Unlike the aristocratic Founding Fathers to the east, however, Boone remains the hero of the common people.

The Call of the Wild

Born in Berk’s County, Pennsylvania, on November 2, 1734, Daniel was the sixth of Squire and Sarah Boone’s 11 children. His Quaker grandfather had come to Penn’s colony in 1713 in search of religious freedom. But Squire Boone, angered when chastised by the Exeter Meeting of Friends for allowing two of his children to marry outside the church, left the faith and the colony, taking his family to North Carolina and settling his brood on the Yadkin River. Young Daniel, profoundly affected by his father’s religious troubles, always professed to be a Christian but never again belonged to any sect or church.

By the time the family moved down the Great Valley of Virginia to the Yadkin, young Boone had already made a reputation in Pennsylvania as an accomplished hunter and marksman. The forest, so frightful to others, had early beckoned to the boy. The freedom he found there was in sharp contrast to the rigid sanctity of the Quakers. The natural rhythms of the land appealed to him far more than the contrived rules of the settlements.

In 1750, with his friend Henry Miller, Boone pursued his first long hunt, following the Roanoke Gap through the Blue Ridge and hunting along the Virginia-North Carolina boundary with great success. Deerskins were a valuable frontier commodity—as good as cash—and the terms buck and dollar quickly became synonymous. Thirty thousand deerskins were exported from North Carolina alone in 1753. The hunts could stretch easily from several months to a year or longer. From 1750 on, Boone was to be a professional hunter.

On August 14, 1756, he married Rebecca Bryan, a tall, dark-eyed, strong-willed beauty 17 years of age. She was by his side for 56 years and bore him ten children—six sons and four daughters. He built them a snug log home on Sugartree Creek in the Yadkin Valley where they lived for ten years, the longest period of time they spent in one place.

Boone, despite his devotion to Rebecca and their growing family, was gone more than he was home. It was but part of the great irony of his life, for he was a family man who was always away from his family. In the same vein he was a frontiersman in flight from civilization who opens the wilderness to civilization. In so doing he would destroy that which he loved most—both his beloved family and his cherished wilderness.

Boone’s long hunts took him farther and farther from home—west to the lands of the Cherokees in eastern Tennessee and south to the Florida homeland of the Seminoles. He and his companions were the first to push beyond the Blue Ridge. They borrowed much from their Indian neighbors, most especially a keen sense of nature’s rhythms.

– From Timothy Flint’s 1833, 1868 reprint “Biographical Memoir of Daniel Boone,” Courtesy Beinecke Library, Yale University –

The Trail to Kanta-ke

In the spring of 1768, an Irish peddler arrived at the Boone cabin seeking shelter. It was old John Findley, who 13 years earlier had regaled young Boone during Braddock’s march with tales of the fabled Kanta-ke. Boone planned a long hunt with Findley to this American Eden, and enlisted his younger brother, Squire; his brother-in-law, John Stewart; and three neighbors to form a hunting party. On May 1, 1769 they departed in search of the ancient “Athiamiowee,” the “path of the armed ones” or Warrior’s Path. This mountain pass, cutting Kentucky north to south, had long been a favored route for intertribal warfare between the Shawnees and Cherokees. The pass had been mapped and named by Dr. Thomas Walker in 1750 as Cumberland Gap. Boone would make the path immortal in the annals of America.

They moved slowly, pack animals loaded down with extra rifles, ball and powder, as well as traps, kettles, rations and salt. Boone brought along a copy of Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels to read to his companions by the evening fire. On June 7, 1769, Boone stood atop Pilot’s Knob and for the first time viewed his fabled “Kanta-Ke.” It was all he had dreamed of and more.

For six months they hunted and trapped, the only limit on their animal harvest being the inability of the camp keepers to dress and pack the deerskins. But others also claimed these rich hunting grounds, and on December 22, Boone’s party was surprised by Shawnees. The warriors confiscated all their goods and hides, but let the hunters go free with a solemn warning. “Now brothers go home and stay there,” declared the Shawnee leader called Captain Will. “Don’t come here anymore, for this is the Indians’ hunting ground, and all the animals, skins and furs are ours. And if you are so foolish as to venture here again, you may be sure the wasps and yellow-jackets will sting you severely.”

Daniel and Ned Boone, Stewart and Neeley continue to hunt and trap for another month. When Stewart failed to return to camp, Boone searched for his brother-in-law but found no trace, save the remains of a campfire and initials carved in a tree. Alexander Neeley quickly departed for home, but the Boone brothers continued the hunt for three more months. Finally, low on powder and shot, Squire returned with the hides and furs to North Carolina in May 1770, leaving Daniel alone in the Kentucky wilderness. In this time Boone explored his “promised land,” making a mental map of every rich meadow, salt lick and mountain pass. These are some of the best days of his life. He later told a friend that he “had three dogs that kept his camp while he was hunting, and at night he would often lie by his fire and sing every song he could think of, while the dogs would sit around him, and give as much attention as if they understood every word he was saying.”

The brothers rendezvoused on July 27 and continued to hunt and trap until the spring of 1771, when they finally headed home. In Powell’s Valley, not far to the southeast of Cumberland Gap, they were surprised by Cherokee bandits and robbed of all they had. Two years of hunting gained Daniel nothing, save a burning obsession for Kentucky. Finally reunited with Rebecca and the children in May 1771, he talked of nothing but this new land and all the promise it held—for a man, for his family, for his nation.

Call of the West

Kentucky was also causing excitement among the land jobbers and capitalists on the eastern seaboard. Their surveyors were soon hazarding the perilous Ohio River route to mark out parcels of land in Kentucky for future development. George Washington had his surveying parties mark off ten thousand acres for him, despite the Crown’s prohibition of settlement beyond the Appalachians. Even Lord John Dunmore, the Royal Governor of Virginia, hired land agents to mark his claims in this Western country. Benjamin Franklin also employed a land agent to look after his interests in the region. He agreed with Washington that any man who missed the “present opportunity of hunting out good lands will never regain it.” The future of America is to be in the West.

Boone, who did not keep company with Dr. Franklin or Colonel Washington, had his own vision for what this new land could become. It was a simpler vision, built around family and community, as well as the eternal quest for a better life. In the summer of 1773, he determined to bring his dream to fruition, taking Rebecca, their first eight children (two more would be born in Kentucky) and five other Yadkin Valley families with him to make a new home in Kentucky.

Driving their cattle and hogs before them, Boone’s party of 40 reached Powell’s Valley in early October. Boone’s 16-year-old son, James, along with five others, trailed the main party, bringing up additional cattle and packhorses. On October 10, just three miles from Boone’s column, they were ambushed by Delaware, Shawnee and Cherokee warriors. A slave named Adam escaped into the forest but turned to witness the horrible torture of James Boone and his companions by the Cherokee renegade Big Jim and his fellow warriors. Boone’s party retreated eastward, with Daniel and Rebecca settling their family on the Clinch River in a cabin offered by a friend. It was to be a dark winter.

The massacre caused a sensation. Lord Dunmore demanded that the Indian villains be given up to colonial authorities, assuring the Cherokee chiefs that he had done all in his power to prevent encroachment upon their lands. He failed to mention, of course, his own investments in Kentucky survey parties. Men on the frontier took more direct action, and within months the Indians had a long list of white atrocities against their people to lament. The Royal Governor, however, faced more serious problems at home with colonial radicals and so decided that an Indian war might be just the thing to open up the Western lands he had invested in, while diverting attention from the political crisis caused by his dissolving of the House of Burgesses. In April he declared war on the Shawnees and their allies. In what came to be known as Lord Dunmore’s War, Boone distinguished himself, winning promotion to captain in the militia.

The brief war, despite inconclusive results, inspired Judge Richard Henderson on a bold scheme to purchase Kentucky lands from the Cherokees and form a 14th colony on the frontier. Although such a purchase was illegal under both Crown and colonial law, Henderson called for a council with Cherokee chiefs at Sycamore Shoals on the south side of Tennessee’s Watagua River. Henderson hired Boone to arrange these treaty negotiations in March 1775. For 10,000 pounds sterling worth of trade goods, the Cherokee chiefs signed away 20 million acres of Kentucky. Old Oconostota, the leading Cherokee negotiator, knew full well that his people had no claim to this land. “Brother,” he told Boone, “we have given you a fine land, but I believe you will have much trouble in settling it.”

Henderson put Boone in command of 30 men with orders to hack out a road along the ancient Warrior’s Path to the Kentucky River, some 112 miles distant. There Boone erected a fort to protect the rent-paying settlers who Henderson hoped would flock through the Cumberland Gap and up the Wilderness Road. While hacking out this path, a grim discovery was made by one of Boone’s axmen. In the hollow of a sycamore tree a skeleton was discovered with a powder horn marked with the initials “J.S.” Boone recognized the horn as belonging to his missing brother-in-law John Stewart.

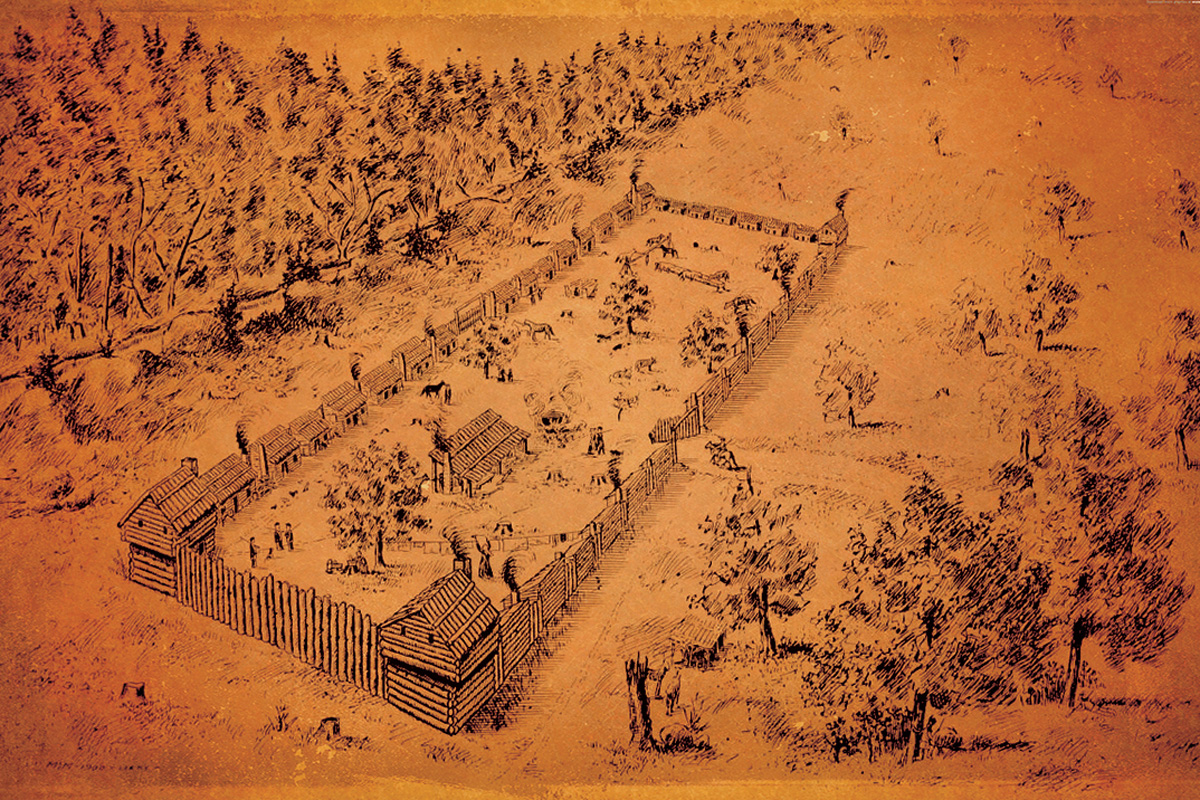

Boonesborough

On April 1, 1775, Boone and his men began construction of Fort Boonesborough near a salt lick some 60 yards south of the Kentucky River. The northern Indians attacked the work parties, killing four and wounding another, and the fort was only saved by the timely arrival of Henderson with reinforcements. The new fort was saved, but not Henderson’s Transylvania Company, for the revolutionary governments of Virginia and North Carolina declared the land sale invalid. Henderson was paid off by his political friends back east, but all of Boone’s land claims were invalidated. Despite this he and his men still supported the revolutionary cause. Boonesborough now stood as the westernmost outpost of liberty.

Henry Hamilton, the British commander in Detroit, offered his Indian allies bounties on American scalps. “Hamilton the Hair Buyer,” as he was known on the frontier, sent Simon Girty to incite the Shawnees to attack Boonesborough and the other Kentucky settlements. The natives needed little encouragement, and raiding parties soon crossed the Ohio River in search of American scalps.

The embattled pioneers sought help from Virginia’s rebel government, but officials there were consumed with plans to repel a British invasion along their coastline and paid little heed to the pleas from the newly created Kentucky County. Young George Rogers Clark was appointed major in command of the Kentucky militia and sent west with a little powder and lead, but no men. Clark mustered his militia on March 5, 1777, with John Todd, James Harrod, Benjamin Logan and Daniel Boone as his captains. They have but 121 men to protect the 280 souls gathered at Harrodsburg, Logan’s Station and Boonesborough.

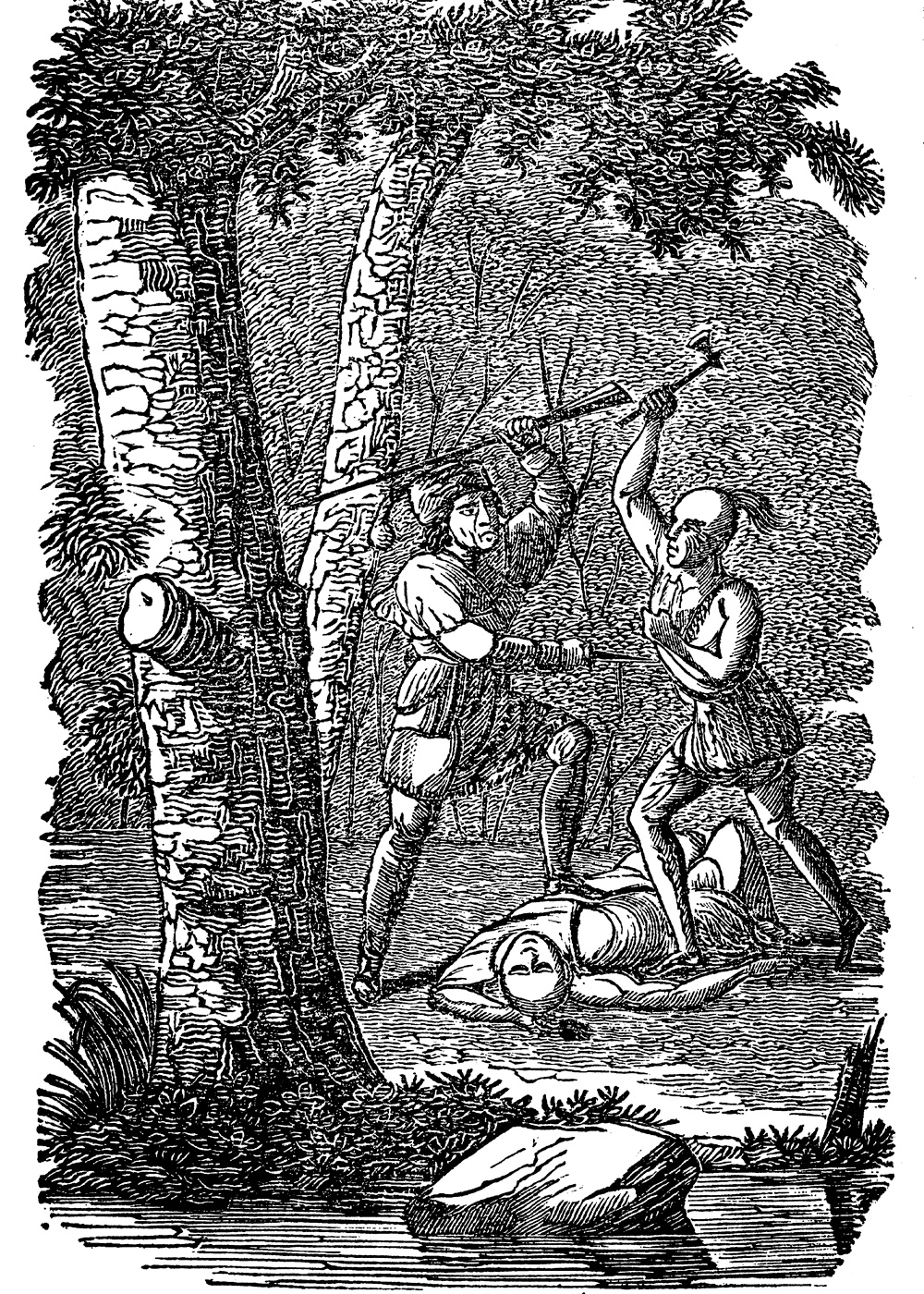

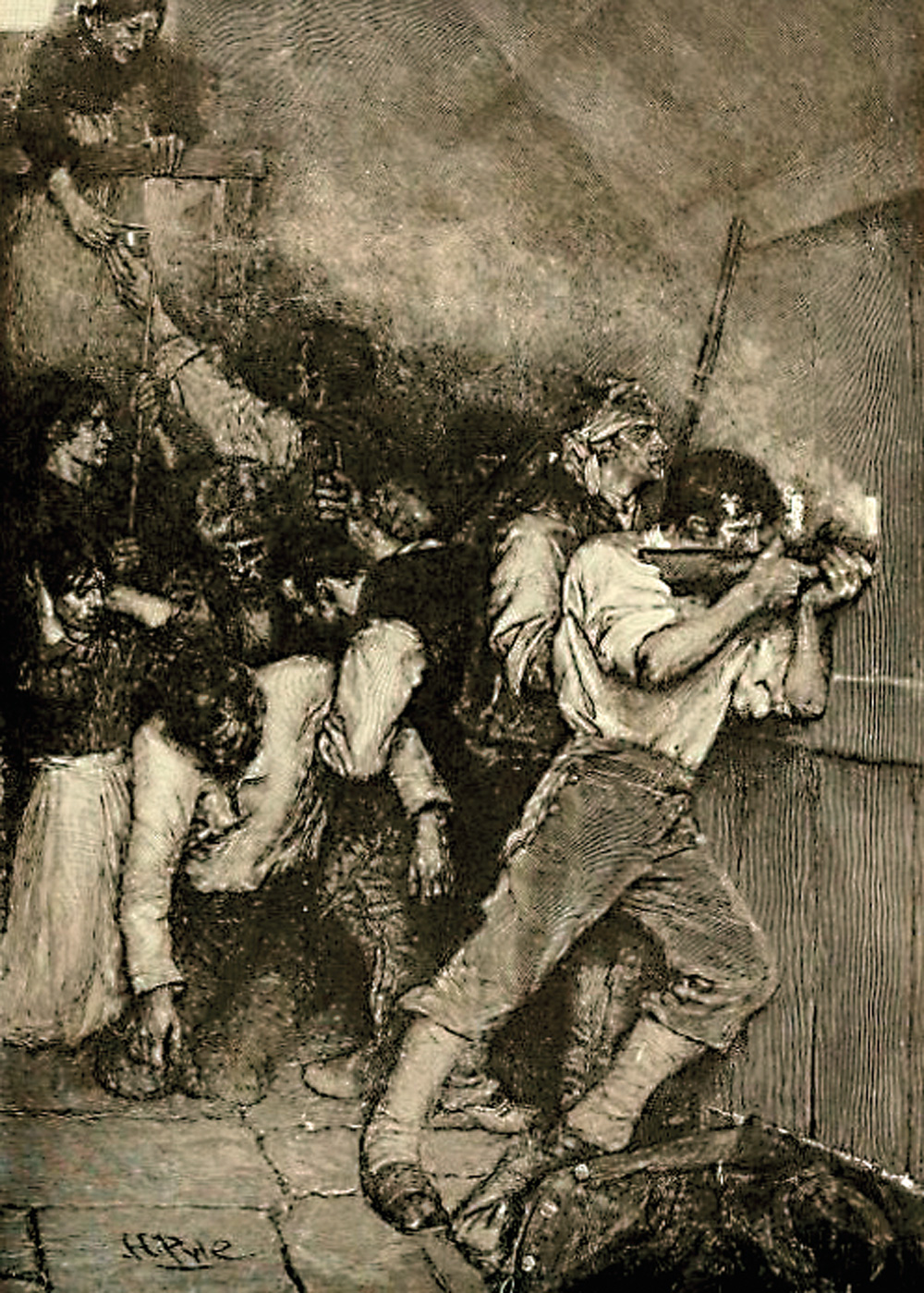

In the same month as the adoption of the Declaration of Independence far to the east in Philadelphia, Boone’s daughter Jemima and two friends, Fanny and Betsy Callaway, were suddenly snatched by Indian raiders while canoeing on the Kentucky River. The kidnapping occurred not a hundred yards from the fort, and the alarm was quickly sounded. Boone hurriedly pursued with eight men, relentlessly following the Indian trail for three days. The girls marked their trail with bits of cloth and used every ruse to slow their captors until finally, on the evening of July 16, Boone’s men rushed the camp. Three Indians were killed, including the son of Shawnee war chief Blackfish, and the girls were rescued unharmed. It is a tale often retold around pioneer campfires and in time en-shrined in American literature as the basis for James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans.

– Illustration from “Harper’s Monthly,” February 1864 –

Siege of Boonesborough

Blackfish’s Shawnees retaliated, taking a heavy toll on the three Kentucky outposts—butchering cattle, destroying crops and holding the settlers as virtual captives inside their fragile stockades. On April 24, 1777, the Shawnees ambushed several men outside the fort and Boone, rushing to their rescue, went down with a shattered ankle. He was saved by Simon Kenton, a young Virginia giant with a mysterious past, who hoisted Boone over his shoulder and made for the fort gate amidst a hail of musket balls. Confined to his cabin for six weeks, Boone would always limp from the wound.

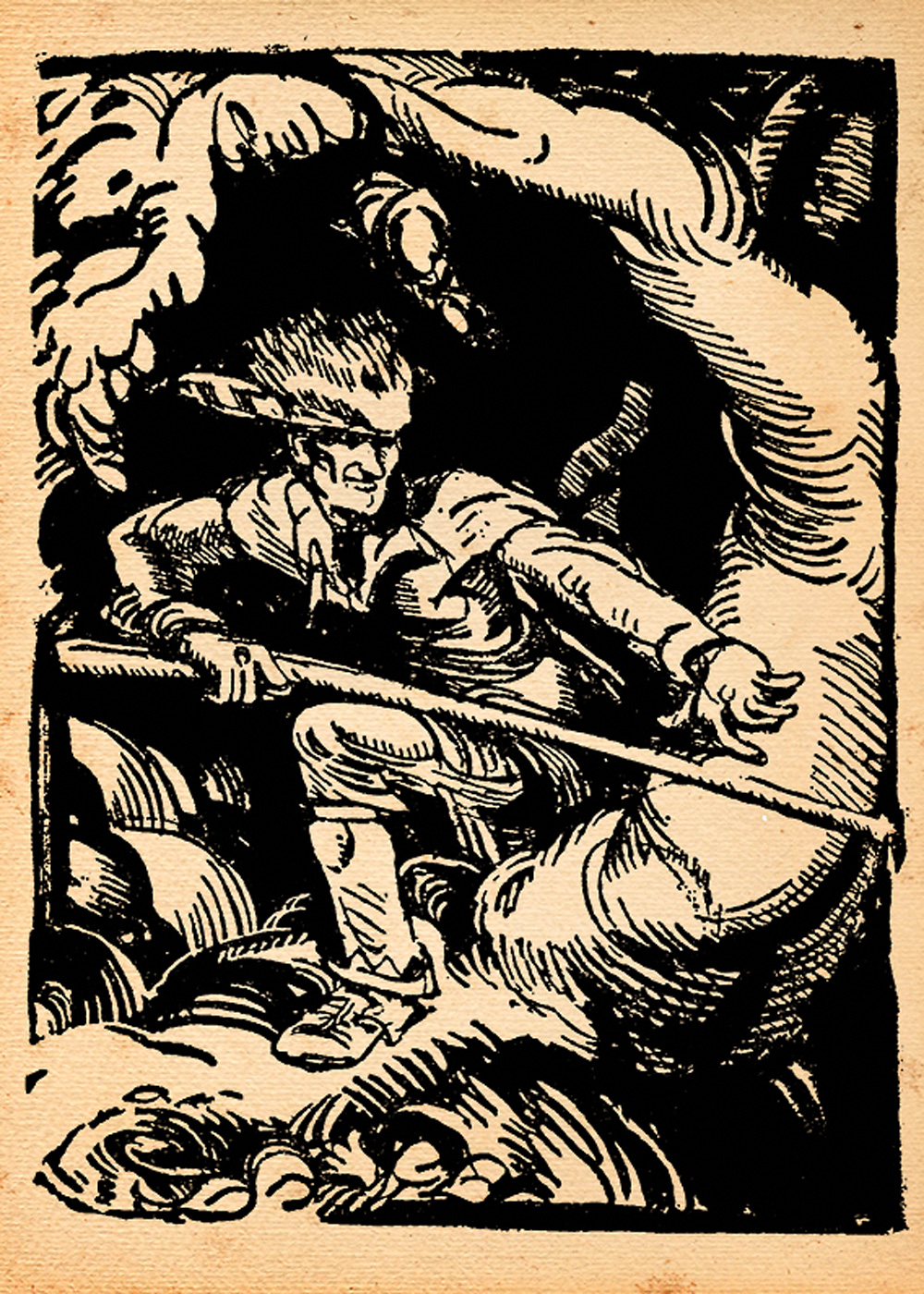

By the time Blackfish lifted his siege late that summer, the settlers were near starvation. Their crops destroyed, they were desperate for salt to preserve the meat that was now their only food. In January 1778, Boone led 30 men to the lower Blue Licks to boil salt for the pioneers. While hunting for his men Boone was captured and taken before Blackfish, who commanded 120 warriors. Boone wisely negotiated the surrender of the salt party in exchange for their lives and he and his men were soon trudging toward the Ohio River.

Blackfish was true to his word that no harm would come to Boone’s men, but the promise did not extend to the man who killed his son. A vote was held among the warriors over his fate, with Boone allowed to make a final argument before the Shawnees. The vote was 59 for death and 61 for life, but to satisfy the losing faction, Boone was forced to run the gauntlet between the warriors. Passing virtually unscathed through them, his courage so impressed them all that he was promptly adopted into the tribe to replace Blackfish’s son and given the name Big Turtle.

The prisoners were taken north to Old Chillicothe on the Little Miami River and dispersed among the warriors. Several were taken to Detroit to be sold to the British. In Detroit Boone was interviewed by Colonel Hamilton, who took a liking to him and attempted to ransom him from the Shawnees. Blackfish having none of this, took his new son back with him to the Little Miami where Boone lived as a Shawnee for five months.

“I was adopted,” Boone later recalled, “according to their custom, into a family, where I became a son, and had a great deal of affection for my new parents, brothers, sisters, and friends.”

In early June 1778, Boone learned that Blackfish planned to lead 400 warriors south to attack Boonesborough. Boone promptly made his escape and, despite his bad ankle, outdistanced his Shawnee pursuers in a mad dash to the Kentucky River. He covered 160 miles in four days, reaching the fort on June 20. There he found many of the disheartened settlers departed, including Rebecca and all his children, save Jemima. Several of those remaining at the fort viewed him with suspicion, for reports had reached Boonesborough that he, like the renegade Girty, had gone over to the Indians.

– Illustration by James Daugherty from Stewart Edward White’s “Daniel Boone, Wilderness Scout,” Courtesy Stuart Rosebrook Collection –

On the morning of September 7, 1778, Blackfish appeared before Boonesborough with 400 warriors, as well as a company of Canadian militia sent from Detroit by Hamilton. Boone had but 60 men and boys to defend the dozen women and 20 children huddled inside the stockade. A parley was held, and Blackfish presented Boone with a wampum belt and a letter from Hamilton offering safe conduct to Detroit for the settlers if they will surrender. Otherwise, no quarter was to be given. Boone’s answer was that his people will fight.

For nine days and nights the battle raged. The Shawnees boldly assaulted the fort with burning torches and flaming arrows, but the little band of defenders held firm. It was as desperate a defense as any in American history, and finally on September 18. the warriors, suffering nearly 40 dead and many more wounded, withdrew. Inside the fort two were dead and four more wounded, including Squire and Daniel Boone. The tiny outpost of the Revolution stood, helping to secure the West for the new republic.

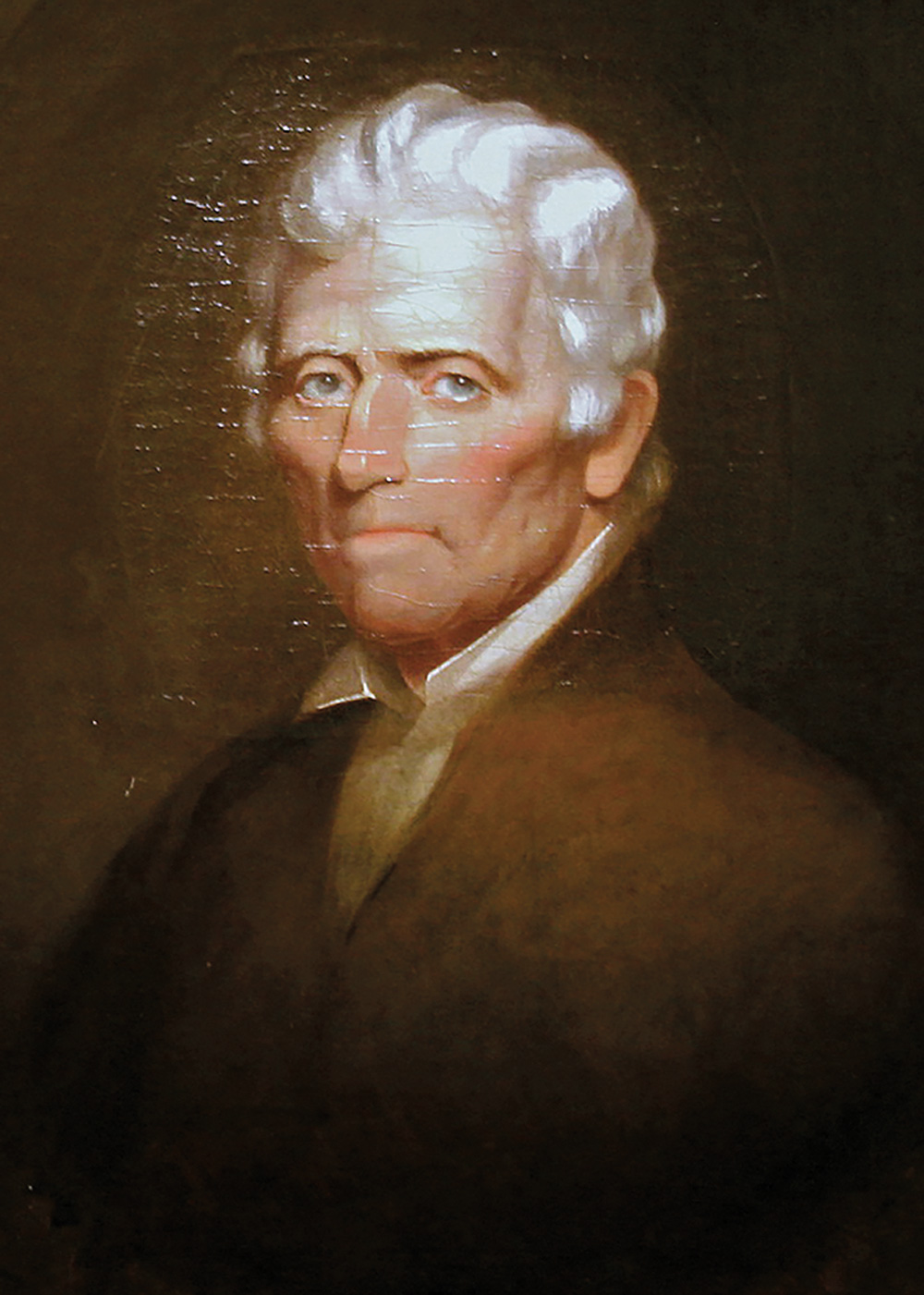

Daniel Boone (below) was made in June 1820, when the great American was 84 years old and residing at the Missouri home of his daughter Jemima Boone Callaway. It is the

only painting made of Boone during his lifetime.

– Courtesy Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery –