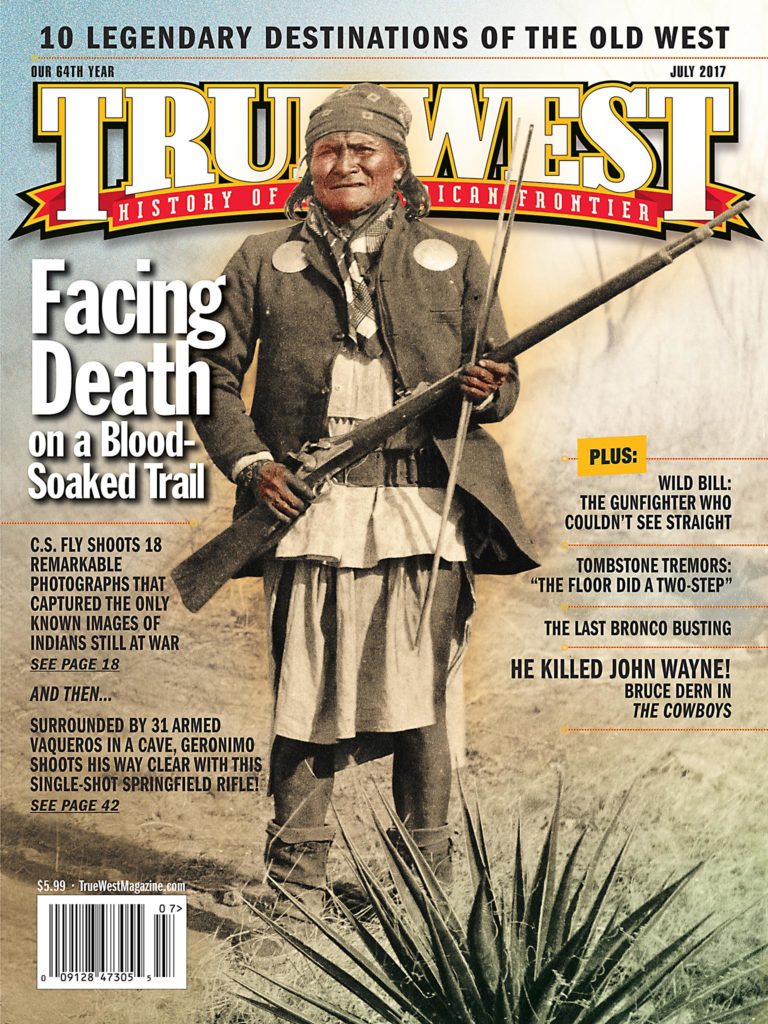

– True West Archives –

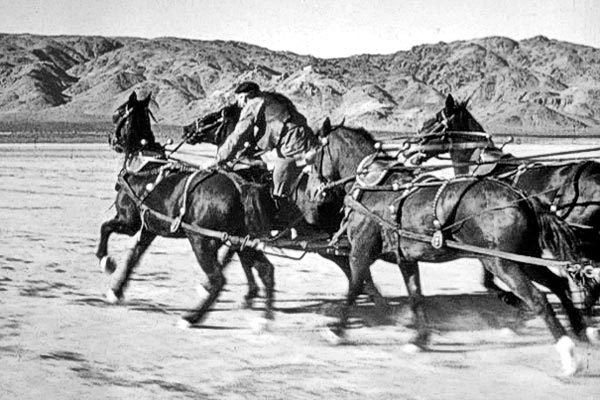

The most memorable action sequence in Stagecoach comes near the end of the 1939 film. Shortly after the river crossing, the passengers expect a smooth ride into Lordsburg, New Mexico Territory, but Apache leader Geronimo and his men have other ideas. They swoop down from a hill to attack, and the stagecoach races for the Mojave Desert’s Lucerne Dry Lake Bed, commencing a moving battle scene that runs relentlessly for an astonishing six minutes, from the moment the unsuspecting Samuel Peacock (played by Donald Meek) catches an arrow in the chest to the first sight of the cavalry led by Lt. Blanchard (Tim Holt).

Shot for three days on location, the Apache chase seamlessly intercuts with studio shots of the actors against rear projections. While doubles portray the other actors in this scene, John Wayne performs his role. With the chase moving at about 45 miles per hour, the stage door swings open and Wayne is seen hanging on it. He scrambles up onto the roof of the coach, lies on his belly and starts firing back at the Apaches.

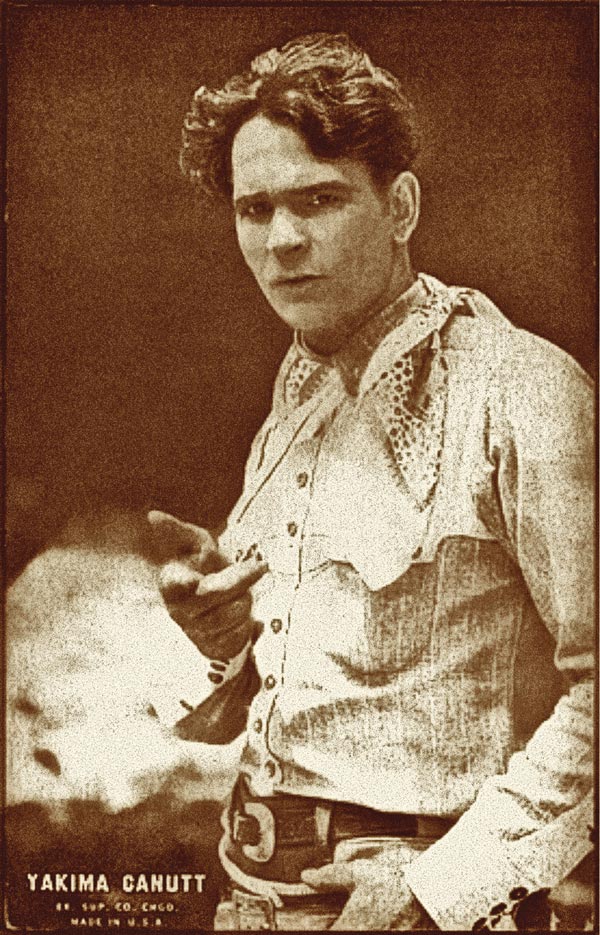

Next comes the sequence that would make a legend. Yakima Canutt first performed this in 1937’s Monogram release, Riders of the Dawn, doubling for Jack Randall, and he would do variations on it for the rest of his career. The stunt is frequently imitated, most notably in 1981’s Raiders of the Lost Ark. Canutt, dressed as an Apache, rides up on the left of the stage’s lead team, jumps from his pony over the near horse to the wagon tongue and begins to stop the lead team.

What comes next made this gag merely extremely dangerous, rather than suicidal. Not visible to the camera were metal bars Canutt had attached between the harness hames on each of the three teams, which kept the distance between the horses at three feet. When Wayne’s Ringo Kid shoots him, Canutt drops between the horses, catching himself on the tongue and letting his back drag. Ringo Kid shoots him again, and Canutt drops all the way to the ground, between the horses.

Canutt crosses his arms across his chest as he falls, which may look odd, but he had good reason to do so. “…the clearance under the coach is critical,” Canutt recalled. “If you were to double your arms with your elbows up, the front axle would strike them. All in all, it is a gag that you could easily rub yourself out with if you make the wrong move.”

When the stage passes over Canutt, he collapses and then rises to his knees—to prove that a person, not a dummy, was in the scene. That last move momentarily scared the hell out of Director John Ford, a former stuntman himself, who’d expected Canutt to fall off the side of a horse, not between the teams. He thought the collapse was real, and that Canutt had been injured.

– All Stagecoach photos Courtesy United Artists –

When the scene was finished, Ford’s three cameramen were not sure they’d caught it. When Canutt told the director, “I’ll be happy to do it again, Mr. Ford. You know I love to make money,” Ford replied, “I’ll never shoot that again. They better have it.”

Of course, they did.

Next in the sequence, the stagecoach driver (played by Andy Devine) is shot in his right shoulder, nearly falls from the wagon and loses the reins for the horses on the right side. He calls to Wayne’s character, and Canutt, now doubling Wayne, leaps from the top of the coach to the first team, supporting himself on their backs (and those hidden bars), leaps to the second team, then the third, straddles the lead right horse and gains control. Although Wayne didn’t perform this stunt, Wayne did act out the last shot of the sequence, in which he rides the horse, sans saddle, at breakneck speed.

Among the other stunts in the chase are numerous dramatic Apache horse falls, some done by Canutt, some by Iron Eyes Cody, and a horse drag, in which an Apache is shot out of his saddle, but his foot gets caught in the stirrup—he’s dragged for several seconds. These actions were shot from a camera car with three cameras rolling, to provide three choices for each shot, so dangerous stunts did not need to be repeated. That these falls and drags were more impressive than in most Westerns was due largely to Canutt’s skill in staging, along with Bert Glennon’s brilliant cinematography; rather than the usual camera paralleling the action, the falls often come right at the camera. From Ramona in 1916 through the Cheyenne series in the 1960s, Glennon’s artistry, particularly in black-and-white movies, would grace films in all genres, including eight of Ford’s finest.

Upon completion of Stagecoach, Ford told Canutt, “Any time I’m making an action picture and you’re not working, you are with me.”

Yet, at a studio party that night, the film’s editor, Otho Lovering, was telling Ford, “I really think you’re going to have one of the best Western action pictures ever made,” when a tipsy Glennon interjected, “Yes, thanks to Yakima Canutt.”

Glennon’s comment was too much for the prickly Ford. Except for a single horse fall by Canutt in 1939’s Young Mr. Lincoln—booked without Ford’s knowledge—the screen’s greatest Westerns director and the screen’s greatest horse stuntman would never work together again.

Henry C. Parke is a screenwriter based in Los Angeles, California, who blogs about Western movies, TV, radio and print news: HenrysWesternRoundup.Blogspot.com