– Courtesy Haynes Foundation Collection, Montana Historical Society –

On May 17, 1876, Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer and the 7th U.S. Cavalry marched from Fort Abraham Lincoln, Dakota Territory, to destiny at Little Big Horn. Not so well-known is the fact that a battery of three .50 caliber Gatling guns accompanied the expedition, mobilized to subjugate the non-reservation, “hostile” Lakota Sioux bands led by Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse in Montana Territory. Second Lt. William H. Low and a detachment of the 20th Infantry had been assigned to the fort to organize this “artillery” component of Brig. Gen. Alfred H. Terry’s “Dakota Column.”

Low’s unit, however, would be denied a role at the Battle of the Little Big Horn, fought that June, when his guns were assigned to Col. John Gibbon’s less mobile “Montana Column” because of a legitimate concern that the Gatlings would impede Custer’s “pursuit of the Indians,” as Custer’s orders of June 22 stated. During a previous cavalry reconnaissance “over very rough ground,” one of Low’s guns had overturned, injuring three men, and was temporarily abandoned, several participants recalled. The four unfit condemned cavalry horses that pulled each gun further justified concerns about the mobility of this precursor to the modern machine gun. Informed that his battery would not march with the 7th Cavalry, Low “wept, almost cried,” remembered Winfield S. Edgerly, a second lieutenant with the 7th Cavalry.

The Montana Column was organized to position troops north of the 7th Cavalry, in order to prevent Indian forces from escaping. The troops instead found Custer and his dead command (263 men out of the approximately 650 troops who fought) when they arrived at the battle site on June 27. The 7th Cavalry survivors had the somber duty of burying their brothers in arms.

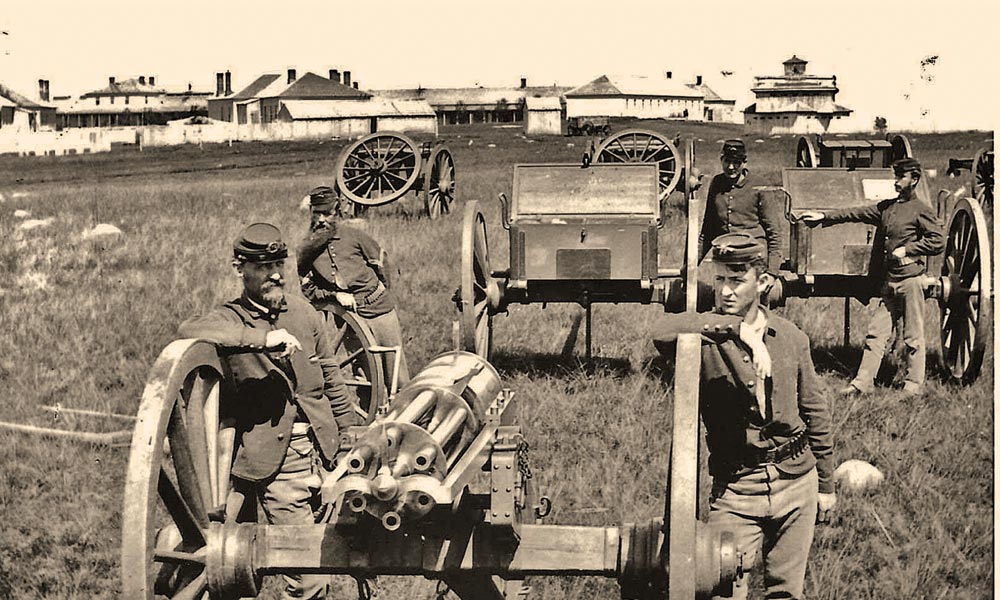

After news spread of the disastrous Little Big Horn battle, F. Jay Haynes photographed a Gatling gun and “crew” against the background of the infantry post at Fort Lincoln, near present-day Bismarck, North Dakota. Located on a bluff overlooking the Missouri River to the east and the cavalry barracks to the south, the infantry quarters are readily identified by the blockhouse near the quartermaster’s commissary and by the two-story building that served as the post hospital. Post records establish that Low’s detachment was stationed there prior to the expedition’s departure.

The Gatling gun that Haynes captured for posterity was probably one that accompanied the Dakota Column “for range,” as reported by Capt. Otho E. Michaelis, the expedition’s ordnance officer. Since it is a one-inch caliber, as opposed to the .50 caliber Gatlings in Low’s battery, this is one of two apparently left at the Powder River Supply Depot. The men in the photo, though, probably belonged to Low’s unit.

– Courtesy Special Collections, United States Military Academy –

Haynes dated this scene June 1877, when he visited Bismarck and “made some over 30 negatives at the Fort (Lincoln) yesterday [June 17].” Several of the other images can, in fact, be attributed to that date. However, Haynes had also been at the post the previous autumn. “The US Government fort is there. I will be able to get some fine Views there as the scenery is splendid,” he told his wife on October 14, 1876.

Details in the photograph and other facts reveal that Haynes erred on his date. The cap of the soldier in the right foreground establishes these enlisted men were members of the 20th Infantry; post and regimental records confirm that no individuals or units of that regiment were stationed at Fort Lincoln in June 1877. Two companies of the 20th Infantry detailed to the fort during the expedition had returned to their normal stations in November 1876.

Moreover, the handmade leather cartridge belt illustrated in this image was typically used during campaigns before the U.S. Army adopted a standard issue, cotton canvas looped belt produced at Watervliet Arsenal in the wake of the Custer disaster. In April 1877, Capt. Michaelis reported that nearly 600 of the new cartridge belts had arrived at Fort Lincoln “in abundant time” for use by the troops in the field that summer.

Finally, some of Low’s detachment remained on duty at the post in the fall of 1876, including Sgt. Peter Monaghan and possibly Cpl. Thomas Tully. The sergeant at the rear left, for example, might be Monaghan. The other noncommissioned officer in front of him bears a resemblance to Hugh Hynds, the battery’s acting first sergeant.

In effect, photographic and historical evidence indicates that members of the Gatling gun battery posed for Haynes in October 1876, soon after the expedition returned to Fort Lincoln.

The image also testifies to the Indian-fighting Army’s diverse uniforms. The sergeant in the foreground wears a four-button sack fatigue coat and stripes, documenting the continued use of Civil War clothing into the 1870s. The private to his right is dressed in the five-button 1874 regulation blouse (albeit modified). His cartridge belt, however, has the 1851 “eagle” belt plate, instead of the simple “US” version adopted in 1872. The dress of the Frontier Regulars was far from “uniform.”

Historical images often speak for themselves. By closely examining this Haynes photograph, we are given a better understanding of its time, place and characters. This treasure of a photograph is among the 9,000 stored in the Haynes Collection in Helena, representing a significant chronicle of the rich history of Montana during the late 19th century, made available to all of us thanks to Jack Ellis Haynes, for preserving his father’s glass plate negatives, and his widow, for donating them to the Montana Historical Society in 1978. Haynes’s fabulous Gatling gun photograph has provided historians yet another close look at the troops tied to the famous Battle of the Little Big Horn.

C. Lee Noyes is the author of “The Guns ‘Long Hair’ Left Behind,” presented at the 1994 Symposium of the Custer Battlefield Historical & Museum Association. He thanks the Montana Historical Society, National Archives & Records Administration and U.S. Military Academy for their assistance with this article.