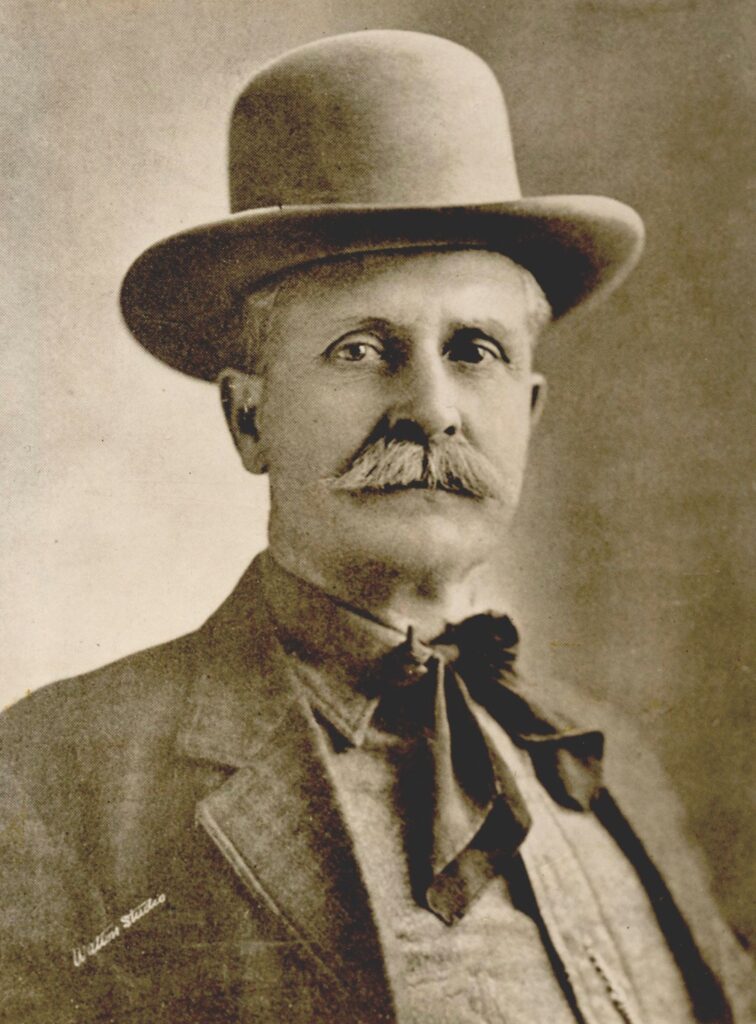

Deputy U.S. Marshal Bill Tilghman’s Courageous Work was the Greatest of His Legendary Career.

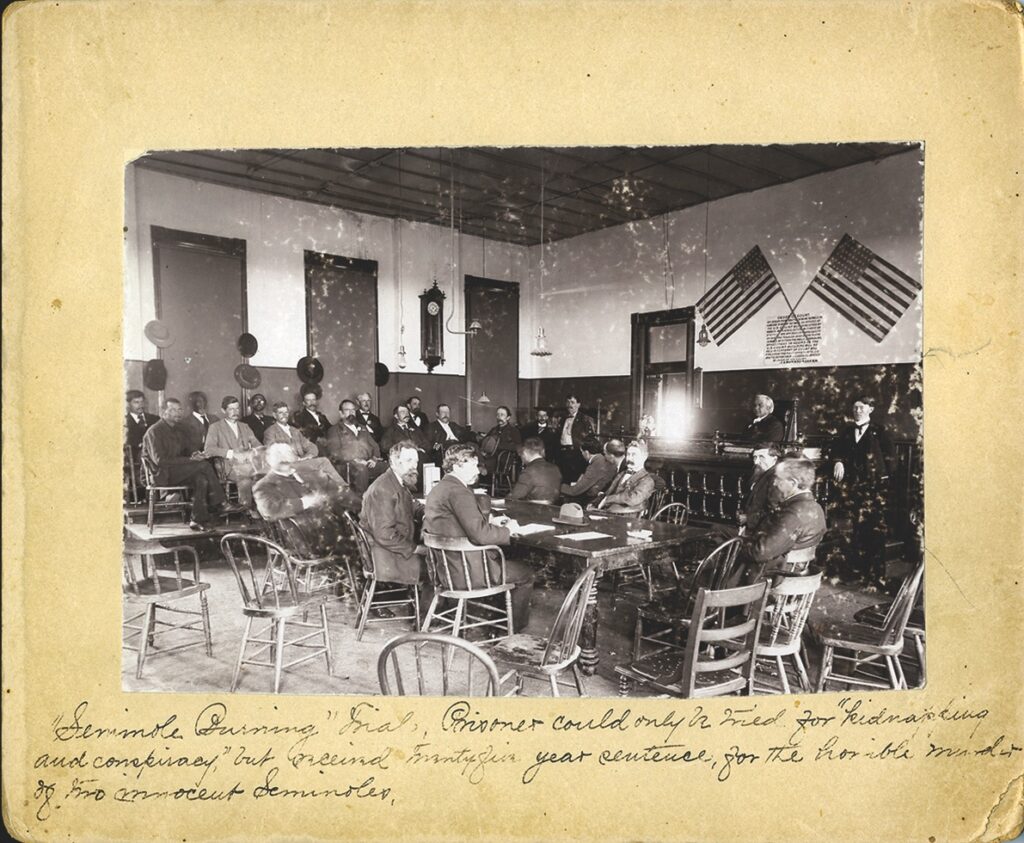

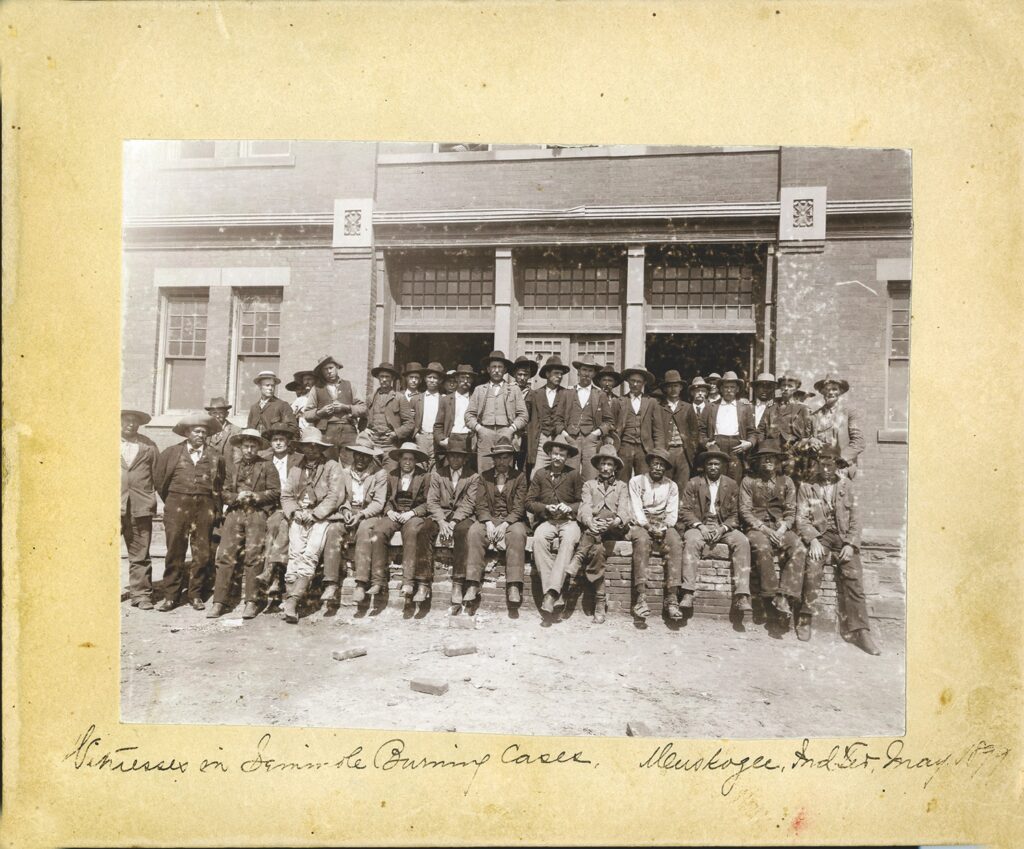

The largest and most sensational criminal trial that involved both the Oklahoma and Indian Territories prior to statehood in 1907, was known as the “Seminole Burnings.” Bill Tilghman, one of the most famous lawmen of the era, played a major role in the investigation and prosecution of the crime. The trial was held in Muskogee, and photos show the jury was racially integrated with Whites, Blacks and Indians. This case was the only one in the nation at that time in which men were found guilty of a racial lynching and sent to jail. It didn’t happen again until late in the 20th century. As great as his law enforcement career was, I feel this was the most important detective work Tilghman was ever involved in on the Western frontier.

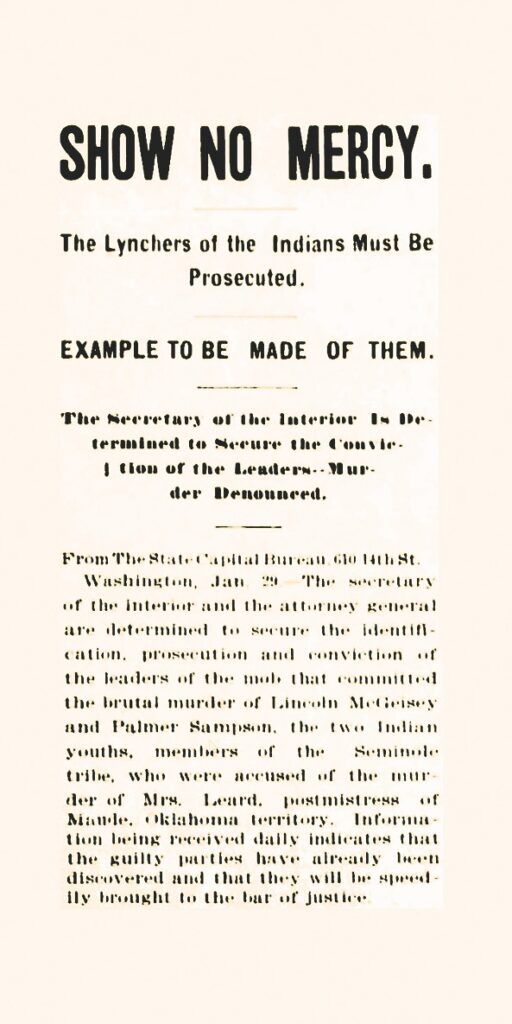

The United States Congress, the Secretary of the War Department and the U.S. Attorney General took part in the effort to restore peace and bring members of the mob to trial. The Secretary of the Interior directed the work of investigating claims and making indemnity payments to the Seminole Indians.

Mystery Killer

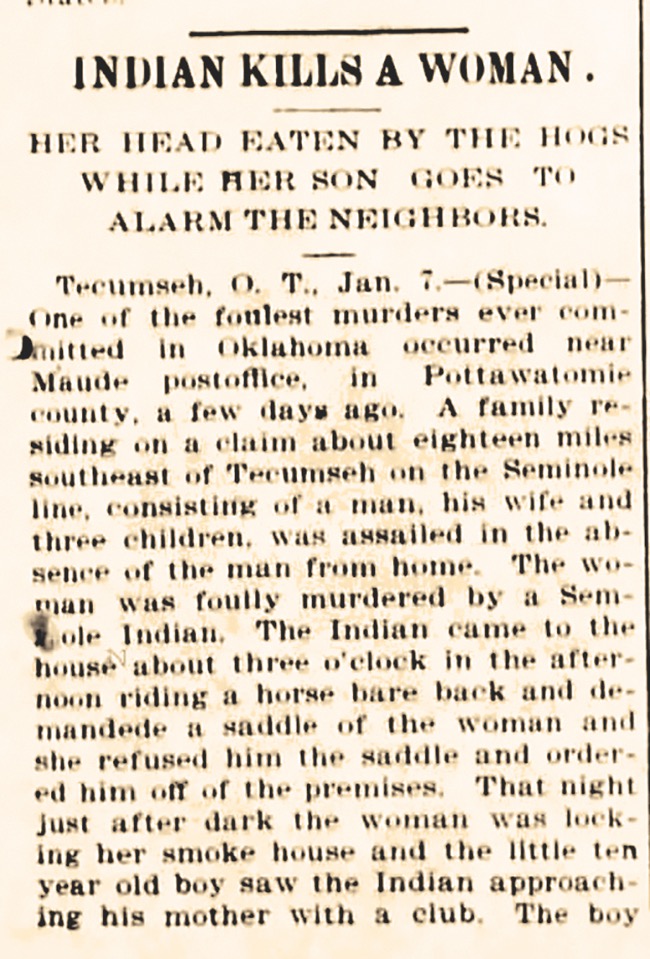

On Thursday, December 30, 1897, a murder was committed near the western border of the Seminole Nation. Julius Leard and his family were tenant farmers in the Seminole Nation, leasing land from Thomas McGeisy, superintendent of Seminole Nation schools. The Leard house was three miles east of the Oklahoma Territory line and one mile west of the McGeisy home. Leard and his family, who lived in Pottawatomie County, had been involved in the illegal whiskey trade in the Indian Territory. Bass Reeves, the famous Black deputy U.S. marshal, whose beat included the Creek and Seminole Nations, described Julius Leard as a regular whiskey peddler who had been in business for “some time.”

On the morning of December 30, Julius Leard had gone to help his brother, Herschel, gather corn on his farm located three miles south of Maud, Oklahoma Territory, and six miles west of Julius’s farm. Mary Leard, Julius’s wife, stayed at their farm in the Seminole Nation with their four children, Frank, eight years old; Sudie, six years old; Nannie, five years old; and the baby, Cora. Julius had left his family alone at the house on other occasions. The surrounding country was quiet and peaceful, and the McGiesys lived only a mile away. The Leards were the only White family living in that part of the Seminole Nation but had many families and friends living around Maud, O.T. The Leard farm was about 18 miles southeast of Tecumseh, at that time the principal town in Pottawatomie County.

About an hour before sunset on December 30, 1897, an Indian on a bay pony with a roached mane rode up to the Leard farm. Mrs. Leard and her children did not recognize him. The stranger was well built, rather stocky and had a scar on one cheek. After entering the yard and approaching the house, the Indian told Mrs. Leard he needed to borrow a saddle, for he was riding without one. Mrs. Leard informed him that since she didn’t know him, she couldn’t loan him a saddle and her husband wasn’t home at the time.

Mary Leard allowed the stranger to get a drink of water. She became suspicious and turned her bulldog loose, but the dog went after some loose hogs in the yard instead of confronting the stranger. Mrs. Leard at that point went into the house and got a rifle. The Indian took note and hurriedly mounted his pony and rode west.

About half an hour later, as Mrs. Leard and children were preparing to eat dinner, the Indian reappeared. Frank saw him first and ran and told his mother the “Indian boy was back.” The Indian entered the house, and Mrs. Leard picked up the baby Cora and ran out the south door of the house. The Indian grabbed the rifle Mrs. Leard had used to threaten him with earlier. He tried to shoot her several times, but the rifle had no cartridges in it. The Indian chased Mrs. Leard around the yard, caught up with her and hit her over the head with the rifle butt. It was a killing blow. Mrs. Leard fell on top of her baby. The stranger moved Mrs. Leard’s lifeless body and grabbed the baby with one arm and threw her viciously onto the floor of the house’s porch. The Indian asked the children about money. Little Frank told him his father had all their money on his person. The Indian walked out of the yard and rode into the darkness.

The next morning, the Leard children with the seriously injured baby, went toward Maud for help. They arrived in town at about 10 a.m. Townspeople located Julius, who was on his way back home after spending a night with his brother. As Julius and a small party arrived at his farm, they found his wife’s body in the front yard. During the night the hogs in the yard had smelled the blood and nearly devoured Mrs. Leard’s head and neck.

Julius Leard and his friend at once began putting a together a posse to locate the killer or killers. Leard did not know a “big” Indian with a scar or one who rode a bay horse with a roached mane. The posse was made up of white men from Pottawatomie County, Oklahoma Territory.

The Posse Becomes a Mob

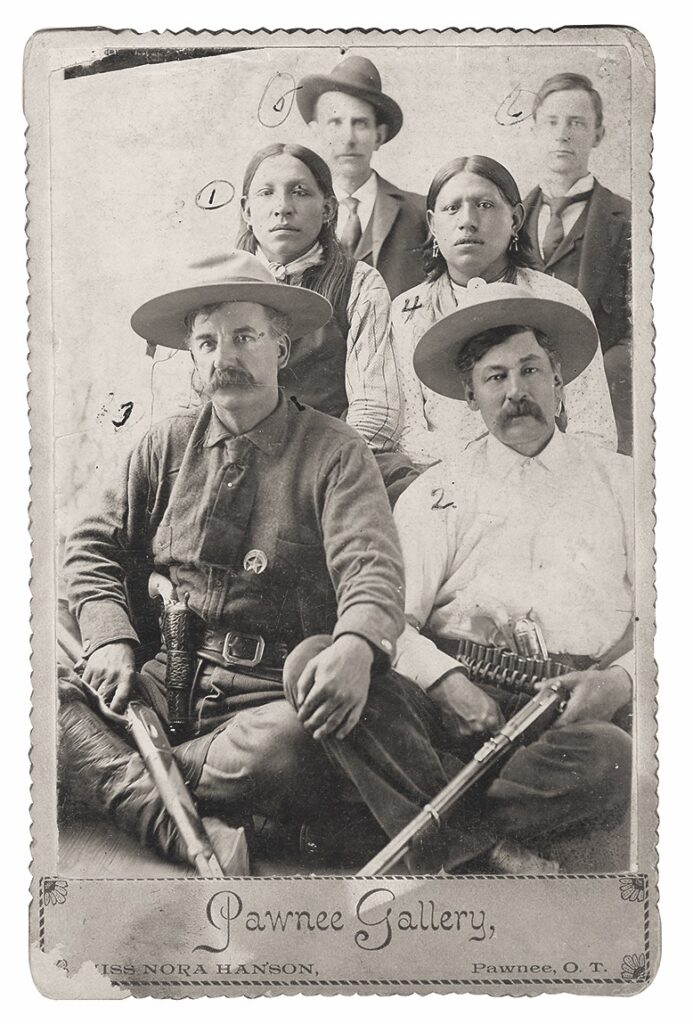

The leadership of the posse was given to Nelson M. Jones, a White deputy U.S. marshal of the Muskogee federal court who was stationed in the Seminole Nation by U.S. Marshal Leo E. Bennett. The week of December 31, 1897, to January 7, 1898, the posse arrested and detained just about every young Indian male they could find. The Leard children couldn’t identify any of the Indians who were questioned. Some of the Indians who were picked up were tortured by the posse and re-arrested later. Several Seminole Lighthorse police officers were disarmed and detained by the posse. The posse became more and more angry as they became frustrated about not being able to find the guilty party. With plenty of alcohol for the posse, the men soon became a large, unruly mob. No official notification of the murder or of the posse’s activities was sent to the Seminole Nation officials.

The method of the mob was to ride along all roads near the border and take every Indian male they found to the Leard house for possible identification of the guilty person by the boy, Frank Leard.

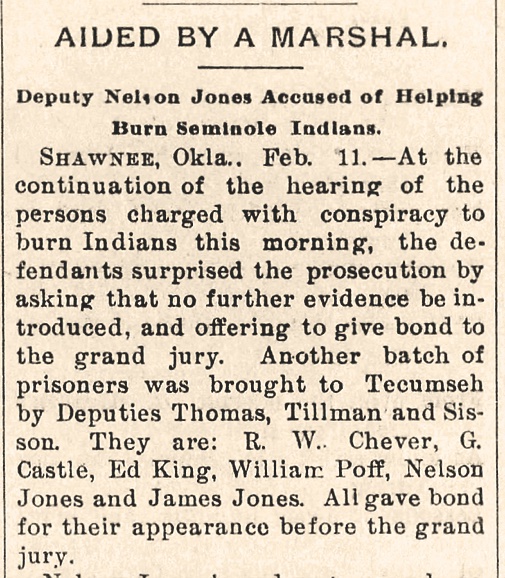

The leader of the mob was Samuel V. Pryor. Born in Mississippi, he claimed to be a former Texas Ranger. His authority superseded Deputy U.S. Marshal Nelson M. Jones, who couldn’t control the mob. Jones, surprisingly, never attempted to contact his superior, Marshal Leo E. Bennett at Muskogee.

The mob set up headquarters at Leard’s farm in the Seminole Nation. Although they couldn’t find who the murderer was, they decided someone was going to die for the crime. Pryor had bragged about his expertise in lynching Blacks in Texas.

The mob chose Palmer Sampson, a fullblood Seminole who could not speak or understand English and Lincoln McGiesy, Thomas’s son, as their victims to be lynched.

The mob from Pottawatomie had grown to about 200 persons bent on revenge. The story now not only had Mrs. Leard being murdered but also raped, which was false. It was true though that her baby died from inflicted injuries.

With Sam Pryor in command, the mob took McGiesy and Sampson to a brush arbor known as the “tabernacle” half a mile south of the Maud post office. This occurred on Friday night, January 7, 1898. At about 2 a.m. on January 8, the innocent Seminole boys were tied to trees with chains and burned alive. There were three White ministers present at the burning.

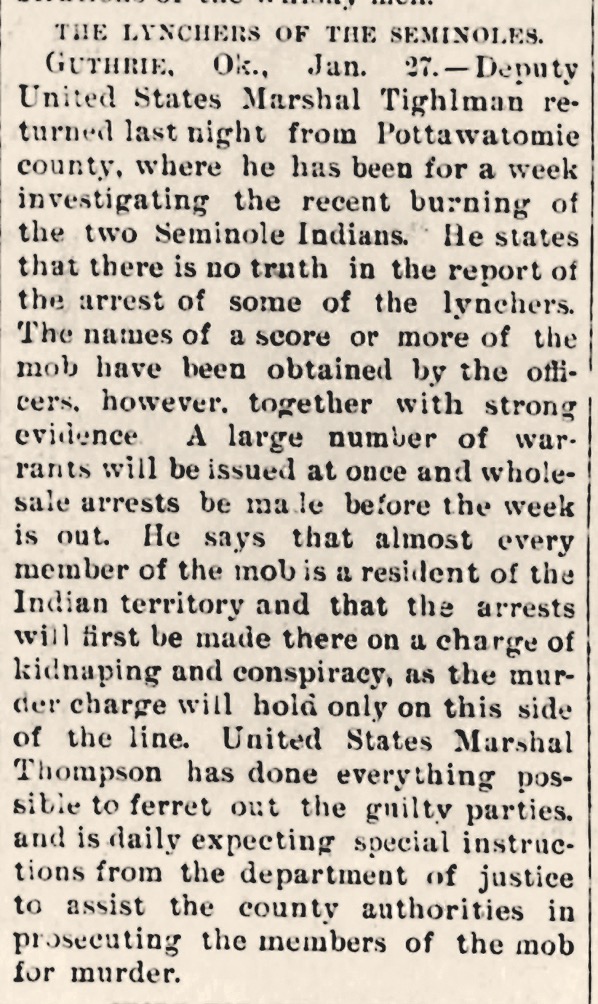

Initially all the newspapers in Pottawatomie County supported the mob and endorsed the notion that the real culprits had been punished. The United States government took a different view and decided to punish the members of the mob. At first things went rather slowly, but by April, a special prosecutor was named, Horace Speed, one of the most important Republicans in the Oklahoma Territory.

It was decided that the prosecution and trial would be a joint effort between the Twin Territories. The trial would take place in Muskogee, Indian Territory, with Judge R. Thomas presiding. There were many deputy U.S. marshals assigned to the case which was given the highest priority by federal officials. Speed, being a former U.S. attorney for the Western District of Oklahoma, was highly thought of as being very capable. The United States Congress voted a special appropriation of $40,000 to find and punish the mob murderers. Bill Tilghman was made the principal investigator for the federal government.

Complicit in Crime

Deputy U.S. Marshal Bill Tilghman early on arrested Deputy U.S. Marshal Nelson M. Jones for complicity in the crime. Other veteran lawmen assigned to the case included Tilghman’s close friend Heck Thomas, William Fossett, N. M. Douglass, W. F. Jones and Tilghman’s longtime posseman Neal Brown, who had assisted Tilghman during his cowtown lawman days in Dodge City.

Tilghman’s wife, Zoe, wrote about the case:

“For many days Bill rode through the rough blackjack hills and tangled bottoms of the North Canadian. He stopped at cabins, meeting sullen answers and glowering looks. If he asked for a meal, he was turned away. Twice a bullet zipped through the leaves above him or threw dirt up in the road.”

Mrs. Tilghman stated also that while gathering evidence, Bill and Heck Thomas rode in a spring wagon with their own food and camp equipment. One of them always rode in the back of the wagon with his Winchester rifle ready, watching their backs. Zoe Tilghman wrote that this case was one of the most dangerous assignments Bill ever had in the territory. Tilghman and Thomas were successful in arresting 15 members of the mob.

Sixty-nine people were eventually indicted for mob action regarding the burning. Deputy U.S. Marshal Nelson M. Jones was convicted at Muskogee and sentenced to serve 21 years in the Missouri State Penitentiary. Andrew J. Mathias was sentenced to ten years in the federal penitentiary at Leavenworth, Kansas. Mont Ballard served seven years of a ten-year sentence at Leavenworth. George Bird Ivanhoe and Sam Pryor were sentenced to three-year terms of imprisonment. Pryor began his time at Leavenworth but was transferred to Ohio State Penitentiary. This was the first time the federal government indicted, arrested and convicted parties for racial lynching in U.S. history.

Seminole Indians who suffered at the hands of the mob filed personal injury claims. Twenty-four members of the tribe received payments that varied from $25, for those who were arrested and detained, to a sum over $5,000 to the heirs of the Indians who were killed. Four members of the Seminole Lighthorse Police who had been detained were paid $50 each.

The Real Killer

Regarding the actual murderer of Mrs. Leard, Bill Tilghman continued to follow up on leads in the case. A 23-year-old Seminole Indian named Keno Harjo had allegedly confessed to the crime in a letter to his sister, a student at Emahaka Mission School. Keno claimed he had killed Mrs. Leard and then fled. His sister informed authorities about the letter and where Keno was hiding out. Bill Tilghman and his posse spent 22 days hunting Keno down in the territory. They finally captured him in the Chickasaw Nation and placed him in the federal jail in Guthrie.

Keno Harjo’s father had traded the bay pony to a Seminole medicine man or “murder medicine,” that is, a charm against being haunted by the ghost of a victim. Bill Tilghman located several persons who had seen the Harjo pony, a bay pacer with a roached mane, in the vicinity of the Leard home on the day of the murder. Keno had traded his saddle for a jug of whiskey at Violet Springs then ridden to his uncle’s house, which took him past the Leard farm. Young Harjo was given bond, and his case never came up for trial. The federal authorities eventually had to set him free for lack of evidence against him.

Deputy U.S. Marshal Bill Tilghman did an outstanding job in tracking down mob members and, apparently, the actual murderer, in this sensational Twin Territories criminal case.