Joseph Glidden’s invention won the West.

In the fall of 1873, Joseph Glidden did what many farmers did and do: he went to the county fair. In this case, it was DeKalb County, Illinois, due west of Chicago and south of Rockford. For Glidden, the annual fair turned out to be life changing.

He saw an invention, created by another local farmer—fencing that featured metal barbs sticking out of a thin wooden rail. The barbs created an incentive for cattle to stay away from the fence and remain in the enclosure. But it was a bit flimsy. The wood could be costly and had to be cut to demand, often shipped long distances.

Joseph Glidden thought there was a better way.

So, he went back home and tested various ideas, using the barbs as the centerpiece. It took about a year, but he eventually came up with something that is now commonplace around the world: barbed wire.

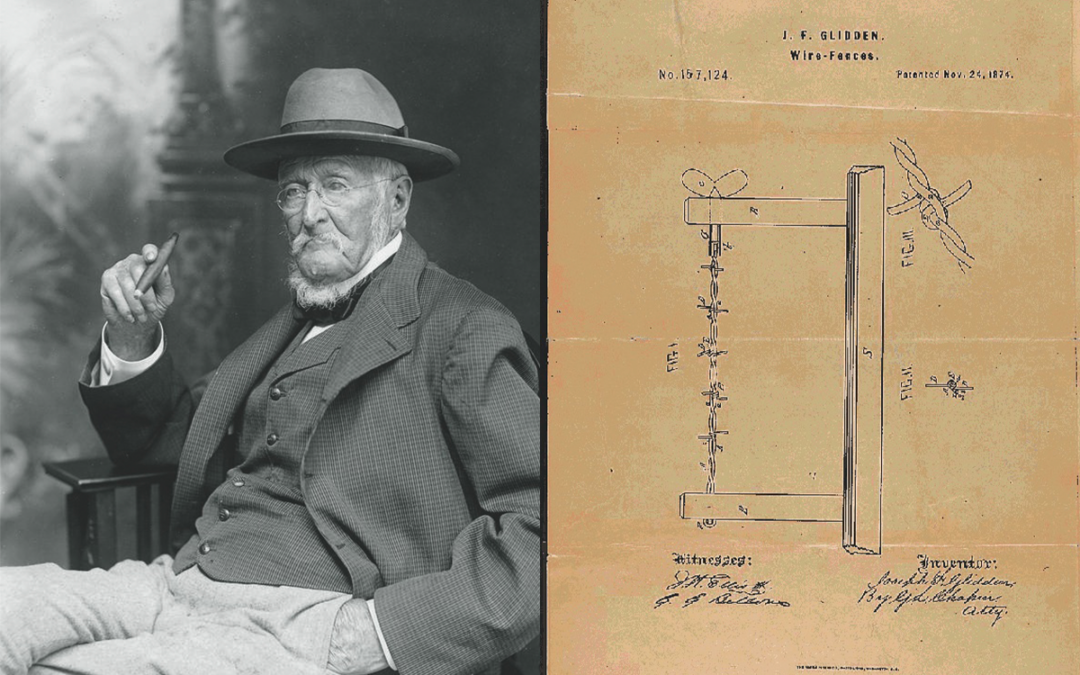

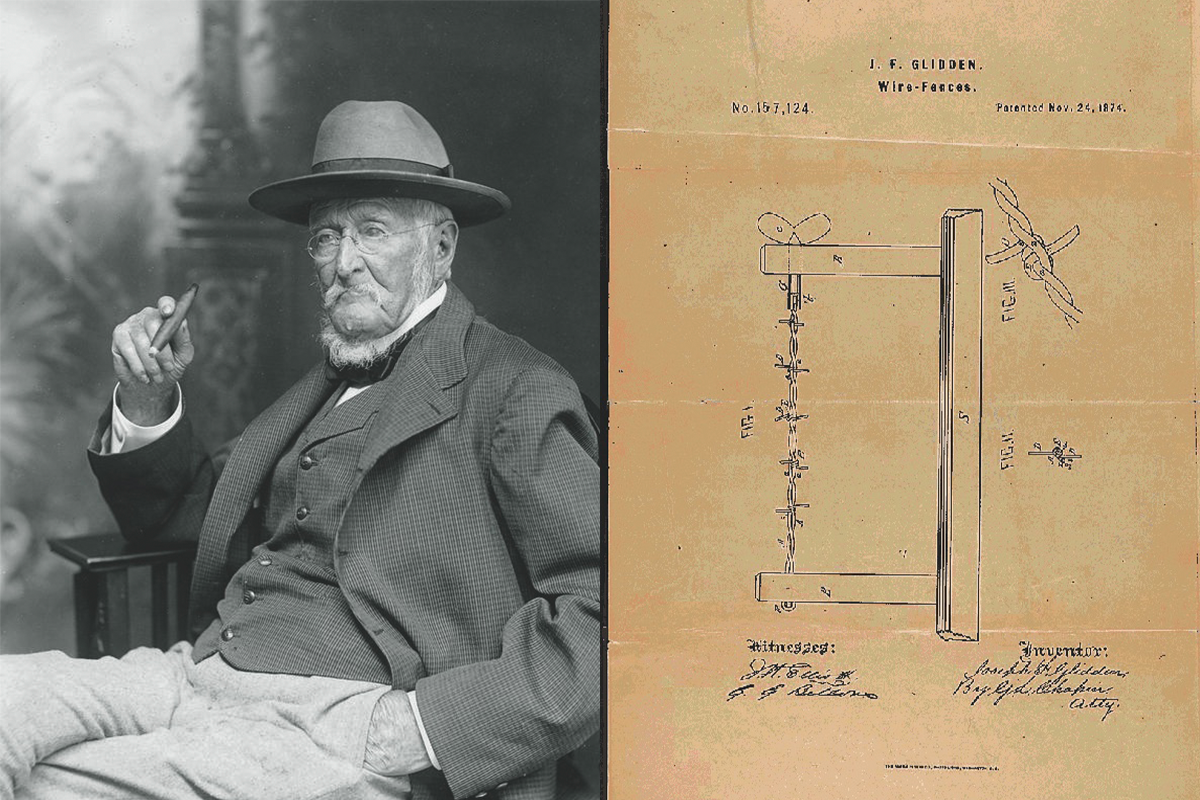

Glidden’s invention—the patent was granted on November 24, 1874—used two intertwined strands of wire to hold the barbs in place. It was easy and inexpensive to manufacture. Repairs and replacements were simple. Glidden referred to this model as “The Winner.”

And depending on who you were, it was just that. Or not.

It wasn’t good for many Indian tribes, who were used to traveling through various Western regions without any problem. It wasn’t good for cattle drives, which required open ranges for travel. And that limited the number of cowboys needed to handle a herd. It wasn’t particularly good for wildlife, like buffalo and deer, who could no longer move unfettered. But it was great for ranchers and farmers, especially those with smaller operations. Barbed wire fences provided a distinct demarcation of their properties. And for those running varied operations, it kept the cattle from getting into the crops.

The West would never be the same. Increased and improved settlement changed the very nature of the land. And Joseph Glidden was the real winner.

But perhaps his true genius was in marketing. He hired sales agents throughout the country, people with local ties who could connect with their neighbor farmers and ranchers. In Texas, Glidden and his state rep Henry Sanborn bought and fenced 135,000 acres of range in the Panhandle. Fifteen-thousand head of cattle were brought in, and what became known as the Frying Pan Ranch was a huge success. Cattlemen across the West saw what could be done and fenced their own properties—and Glidden’s fortunes continued to grow. By the time his license expired in the 1890s, it’s estimated he’d made more than a million dollars. Good investments increased the fortune.

But such success breeds competition—and legal issues. Two other farmers who had attended that same 1873 county fair had come up with their own barbed wire concepts. They challenged Glidden’s patent, and the cases took years to move through the justice system. Finally, in 1892, the Supreme Court ruled in Glidden’s favor.

For the rest of his life, Glidden ran a small business empire from his farm in Illinois. He had been a civic leader well before the invention of barbed wire, and that never changed. He showed a great interest in education—Glidden served briefly as a teacher before going into farming. In 1898, he gave 63 acres of his homestead to help start Northern Illinois State Normal School, later renamed Northern Illinois University.

Glidden saw all the changes by the time he died at age 93 in 1906. He’s buried in DeKalb’s Fairview Cemetery—no, there’s no fence around him or the mausoleum that holds his remains.