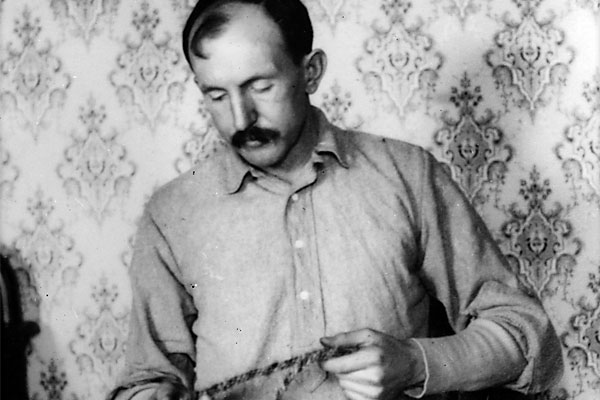

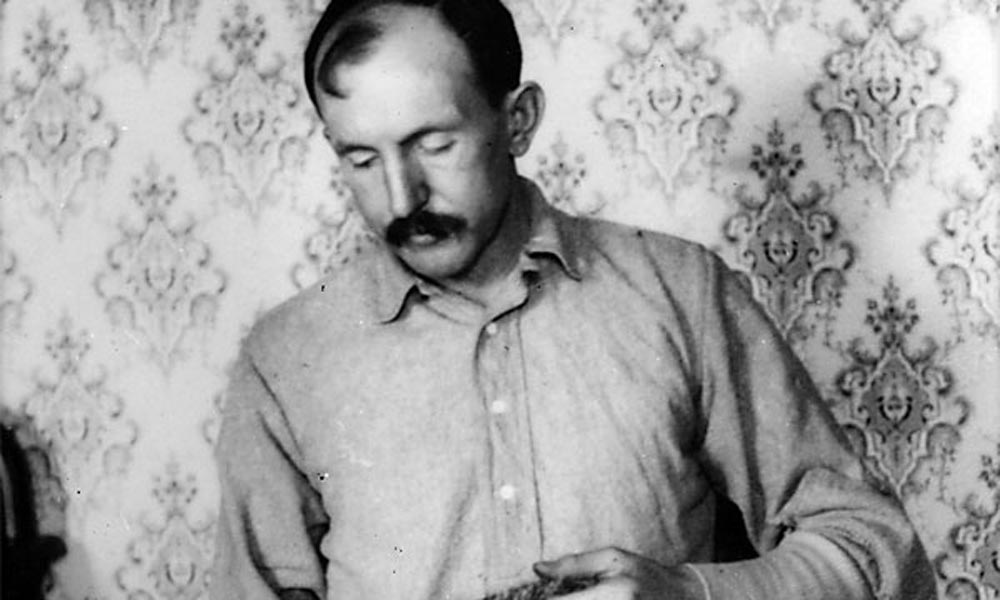

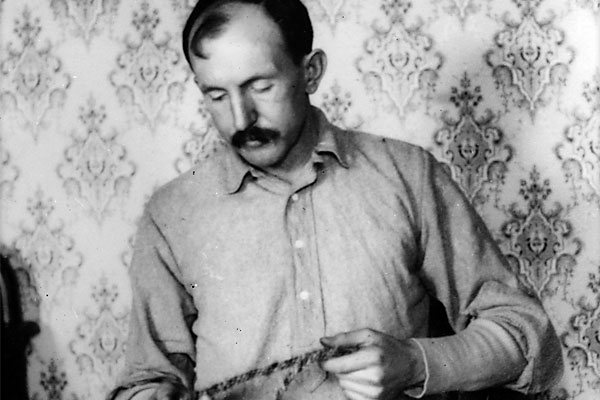

Incompetence is not a word to associate with Tom Horn, for from his teenage years until his death, he more than once proved he was the opposite. Of course, the area in which he showed the most competence (and for which he is best known) was in killing range rustlers from ambush.

Born in 1860 to Thomas and Mary Horn, then living in northeast Missouri where they farmed east of Memphis, Tom had two older brothers, Charles and William, and a sister Nancy, plus one brother who had died at a young age before Tom’s own birth. Later there would be other children in the family.

Tom began proving his competence at a young age, hunting with his loyal dog Shed. The boy, following an argument with and whipping by his father, struck off on his own at age 14. Traveling west, he first landed in Newton, Kansas, where he worked on the railroad. He and older brother Charles spent some time in the livery business in Kansas, but Tom was on his own by the time he struck Dodge City where he remained at least long enough to fight with some cowboys.

Headin’ to Dodge

To follow Tom Horn’s route today, start near Memphis, Missouri, and travel west on U.S. Highway 136 to Bellevue, Kansas. Then turn south on U.S. 81 to Newton, before driving west on U.S. 50 to Dodge City. This town is best known as a cowtown, and some businesses from that era have been recreated on Front Street; a city trolley tour will take you past all the historic sites.

Leaving Dodge City, Horn followed the old Santa Fe Trail route, which you can do by driving U.S. Highway 50 to La Junta, Colorado. Just west of Dodge City is an interpretive area where you can clearly see the ruts and swales left behind by the freight wagons traveling the Santa Fe Trail. Once at La Junta, turn southwest on U.S. 350 to Trinidad before taking Interstate 25 to Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Stagecoach Runs

Horn hit Santa Fe in late 1874, and by the following January had landed a job as a driver for the Overland Mail Stage Route, making a regular run between Santa Fe and Prescott, Arizona.

While Horn may not have spent much time enjoying the delights of Santa Fe—he was, after all, only about 15 years old at the time—this is a place you certainly want to explore. The Palace of the Governors has a historic and architectural appeal that resonates today, just as it would have during Horn’s time in the city. Now surrounded by eclectic shops selling art, jewelry and clothing, the Santa Fe Plaza intrigues and appeals to many tastes. You’ll find good dining, nearby lodging and local Indians selling their wares.

Horn first saw the open country west of Santa Fe from the seat of a stagecoach, but you can travel in modern style—in the air-conditioned comfort of your car. Even so, the scenery remains much the same: broad vistas and stunning buttes and bluffs where some of the native people live in homes/cities that have existed for centuries. Take Interstate 40 to Flagstaff, Williams and Ash Fork, Arizona, then turn south on Arizona Highway 89 to Prescott, the end of the line for Horn’s stagecoach run.

Now certainly the young man did not make that entire trip as a routine run, but he worked his way from Santa Fe west and, eventually, after about a year of traveling, made it to the terminus in Prescott. Later he would say that his work on the Overland Mail Route gave him a real education, “My feelings were so different and my life was so different from what it was at home that it seemed to me then as though I had been all my life on a stage line,” he wrote in his autobiography, “… but I had learned more in that year than in all my previous life.”

Chief of Scouts

Once in Prescott, Horn quickly picked up Spanish (a language he may have started learning while traveling the Santa Fe Trail and living in Santa Fe). By 1876, he hired on as a Spanish-English interpreter at the San Carlos Indian Agency, working for Al Sieber, chief of scouts for the 5th Cavalry. Then only 16, Horn took his turn at cooking, night herding and doing general work around the camp, but soon he was in charge of herding livestock for the Army quartermaster at Fort Whipple.

Always a civilian employee, Horn learned packing from Sieber, participated in scout forays against the Apaches and became chief of scouts in 1885, working for Lt. Marion Maus in the general command of Capt. Emmet Crawford. His competency in Spanish helped get him the job, while his ability with animals helped him keep it. During a scout into Mexico, near Nácori, Mexicans shot Crawford in the head, killing him. One of their bullets also struck Horn in the arm—the third time he was wounded while serving with the Army.

Although he left the scouts for a time, Horn was back in civilian service during the final hunt for Geronimo, playing at least a background role in the capture and incarceration of that old warrior. Horn also bounced around the West a bit. In 1880, he was mining in Cripple Creek, Colorado; in 1887, he was mining in Arizona, became involved in the Pleasant Valley War and likely killed an old man named Blevins—or a Mexican who was a rival for a woman. Still in Arizona in 1891, he won the steer roping at a rodeo in Globe, proving his ability at riding and roping, skills learned from his earliest days on the range.

To stay on his route, from Prescott, travel east on Highway 69 to I-17, then north to Camp Verde before driving east on Highway 260 and Highway 67/200 to Payson. From there, head south on Highway 87 and east on Highway 189 to Tonto Basin and the San Carlos Indian Reservation near Globe.

Just as Horn eventually left Arizona and headed north, you can travel northeast from Globe on U.S. 60/Highway 61 back to I-40; follow it east and then strike I-25, which takes you north into Colorado and Wyoming.

Brushes With the Law

Horn worked for the Pinkerton Detective Agency for a time, a position that took him to other areas of the West, including Reno, where he was arrested for robbing a faro dealer. This is his first known true brush with the law. Taken to jail, he was released on bail that likely the Pinkertons posted. He then went to court in two trials; the first ended in a hung jury, and the second found him not guilty.

By 1892, Horn was in Cheyenne, Wyoming, where he would spend most of his remaining years. His reputation as a competent scout, livestock handler, investigator and, yes, gunman, led to a position with the powerful Wyoming Stock Growers Association as a range detective. Had he continued living in the Southwest, possibly Horn’s name would not have become one of the most recognized in the West. But in Wyoming, he soon had a reputation for ability and ruthless intervention on behalf of the cattlemen. He readily admitted he had a “system” and that his manner of dealing with range rustlers “never failed.”

While he no doubt dispatched men in both southern Wyoming and the Brown’s Hole area of Colorado during his tenure as a range detective, the killing that became Horn’s undoing involved a 14-year-old sheepherder’s son, Willie Nickell. Although he was tried, convicted, sentenced to die and eventually hanged for the crime, in Wyoming today, you will find people who firmly believe Horn did not actually pull the trigger on Nickell. (Stand me to a shot of Jack Daniels, and I’ll tell you how I come down in that argument.)

Today in Cheyenne, you can stay in the Nagle Warren Mansion, one of the homes in an area known as Cattle Baron’s Row, which is now a bed and breakfast, or the Plains Hotel located just down the street from where Horn made his infamous confession to the killing of Willie Nickell. While in Cheyenne, take time to visit

the Old West Museum at Cheyenne Frontier Park and the Wyoming State Museum, or enjoy a walking tour of the downtown area.

Horn reached the end of his rope—literally—in Cheyenne, while his old friends Charlie and Frank Irwin sang, “Keep Your Hand Upon the Throttle and Your Eye Upon the Rail,” as his strongest ally John Coble looked on. His body was buried in Boulder, Colorado.

For more on Old West hangings, read Frontier Doc.