APRIL 9, 1905

Navajo County Sheriff Chet Houck and his deputy Pete Pemberton hop a train from Winslow, Arizona, to Canyon Diablo (Devil Canyon), 26 miles west of Winslow. A saloon robbery the night before at Winslow’s Wigwam Saloon netted two suspects less than $300. After a search of the small railroad town turned up nothing, the lawmen discovered seven silver dollars in the dirt next to the railroad tracks and surmised the robbers jumped a slow moving freight and the coins must have spilled out of overloaded pockets.

Arriving in Canyon Diablo at dusk, the two lawmen question trader Fred Volz, who confirms he has seen two strangers in town earlier that afternoon. As the three stand talking beside the trading post porch, the two suspects, William Evans and John Shaw, appear on the street and are seen heading toward the depot.

The lawmen step lively as Sheriff Houck pulls his pistol and loudly identifies himself, at the same time commanding the suspects to halt.

“Nobody searches us,” one of the two outlaws snarls as they turn to face the lawmen. As the lawmen rapidly approach, the robbers pull their pistols and all four begin firing at point-blank range. Houck advances as close as four feet. A thunderous volley splits the evening air, with all four adversaries emptying their weapons. The taller outlaw, John Shaw, is hit in the head by one of Houck’s bullets and goes down. Pemberton wounds the other suspect in the left leg, and he goes down but aims point blank at Houck. A split second before he fires, Pemberton, with his final shot, hits the outlaw in the left shoulder, throwing off his aim. The outlaw’s bullet goes through Houck’s coat on the left side, skimming his stomach and cutting an exit hole through the right side of the coat.

The quick fight is over in a flash of muzzle fire, with one of the outlaws dead and the other seriously wounded. Both lawmen escape without a scratch.

The Devil’s Town

An the end of the track, a town sprang up at Canyon Diablo when the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad track layers reached the formidable canyon in 1880. Construction was halted until a bridge could be built over the canyon. The first delay happened when the pre-fabricated bridge arrived at the site and was found to be a foot short. A further delay was caused by financial difficulties; several years passed before the railroad bridge was completed.

According to folklore, the main drag of the small berg was called Hell Street and boasted 14 saloons, 10 gambling houses, four brothels and two dance halls. All of them ran 24 hours a day. Various sources have claimed that killings were rampant with some 35 killings taking place in a short period (although this is convincingly disputed by historian John Boessenecker). Legend says the first peace officer hired to tame the town pinned on a badge at 3 p.m. and was laid out for burial at 8 p.m. Five more men put on the badge, but none of them allegedly lasted more than a month before they too were killed.

Once the 541-foot-long railroad bridge opened on July 1, 1882 (seen at left), the town began to die. Still wild, the remaining residents requested that the army take over law enforcement. Before “law and order” arrived, the town was pretty much dried up and the lawless drifters had moved on.

One Last Drink for A Dead Drunk

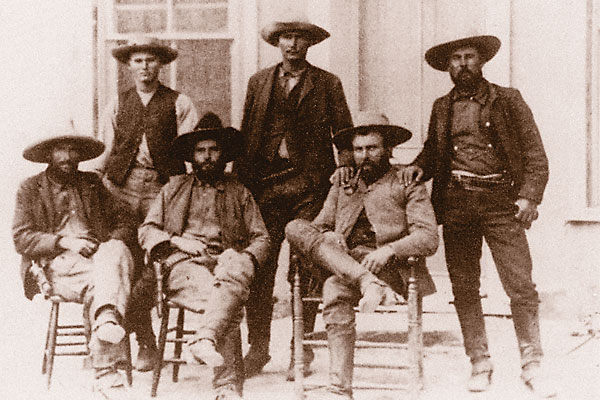

Cowboys from the Hashknife cattle outfit in Northern Arizona hear about the shoot-out that took place the night before and decide to give outlaw John Shaw one last drink of whiskey. They heard that the two cowboys had robbed the dice players at the Wigwam Saloon and left before touching their drinks.

Fifteen men (some cowboys and some just local drunks) take the train to Canyon Diablo and wake up trading post owner Fred Volz to get shovels from him (Volz provided the pine box for the burial).

“We stopped at the depot and had a few more drinks and then we went and dug the grave open with the shovels,” cowboy Lucien Creswell later says. They lift Shaw’s body out of his grave to give him his drink, take a few photos, and then place him back in the casket with the bottle of whiskey.

The Hashknife Outfit: A Deadly Reputation

The cowboys who worked for the Hashknife cattle company in its early years (1885-1889) were a motley crew with shady pasts and many an alias. More than a few rustled cattle from their employers (and by some accounts broke the company) while terrorizing Mormon settlers along the Little Colorado River. A few took part in the deadly Pleasant Valley War between cattlemen and sheepman south of their range, even though it wasn’t their fight.

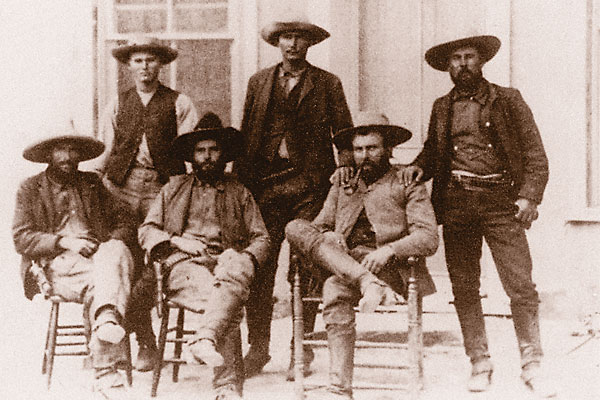

They naturally hung out in Winslow and Holbrook saloons, as seen here in the Fashion Saloon in Winslow. The photo, taken in 1899, six years prior to the Canyon Diablo shoot-out, shows quite a few Hashknife cowboys, including Lucien Creswell, Bill Balcom, Frank Black, Cap Begnal, Tom Williams, George W. Hennessey, Ed Bargman, Doug Johnson, Frank Dane and Johnny Hoffman. The Wigwam Saloon, owned by former Hashknife cowboy Pete Pemberton, would be the site of the robbery that leads to the Canyon Diablo shoot-out.

Aftermath: Odds & Ends

The lawmen discovered $271 in stolen silver dollars on the two men. Wounded robber Smythe (a.k.a. William Evans) refused to talk, and the dead outlaw John Shaw was buried without ceremony. Smythe was returned to Winslow, where he was tried, convicted and sentenced to nine years in the Yuma Territorial Prison.

***

The night after the shooting, Hashknife cowboys were drinking in the Wigwam Saloon and remembered that the robbers had paid for two shots of whiskey which they left behind in the robbery. Intent on rectifying the “injustice” 15 drunken Winslowites took the train to Canyon Diablo. They borrowed a shovel from trader Volz and he also gave them a Kodak box camera to take a photo of the dead outlaw in hopes that someone would identify him (and pay a reward).

***

Pulling him out of his casket, the cowboys leaned him against a grave barrier and poured a drink between his clenched teeth. After posing for pictures, the cowboys reburied the outlaw with the unfinished bottle of whiskey. Although the photos were widely distributed, no one ever came forward to identify the robber.

***

Seven months after the Canyon Diablo gunfight, Pete Pemberton drunkenly shot and killed Marshal Joe Giles in the Parlor Saloon in Winslow. Sheriff Houck refused to charge his trusty deputy. Outraged citizens brought pressure on other authorities to arrest Pemberton in nearby Holbrook. Because of local anger and resentment, the trial was moved to Prescott. Found guilty of second-degree murder, Pemberton was sentenced to 25 years, but he was pardoned after serving only a few years.

***

Sheriff Houck later lost his bid for reelection by a landslide.

Recommended Read:

Hash Knife Brand by Jim Bob Tinsley, published by University Press of Florida.