–Courtesy Jerome State Park –

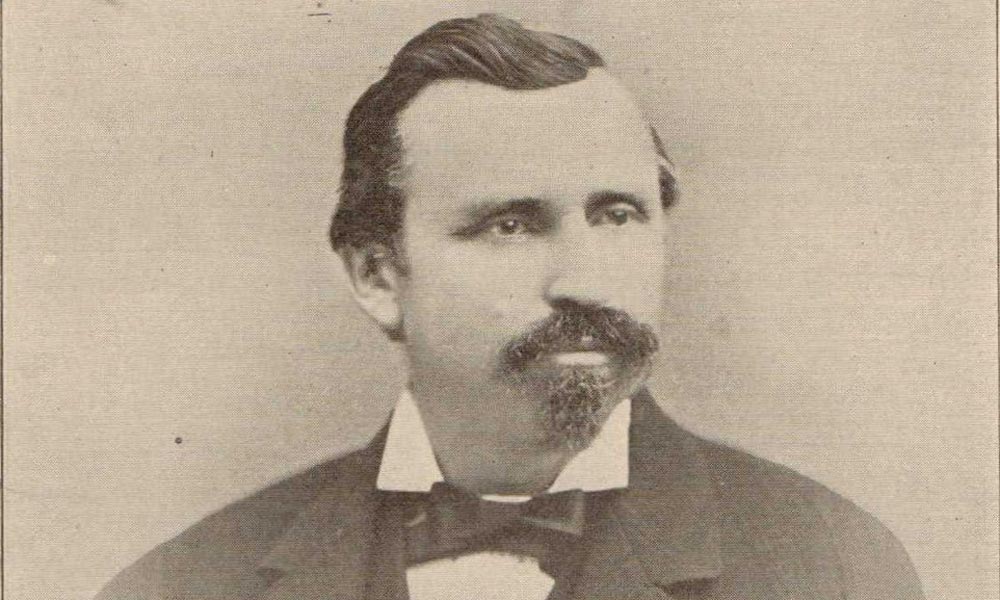

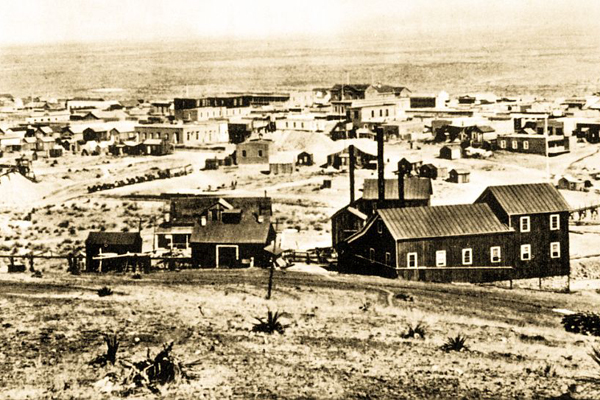

On May 3, 1887, in Tombstone, Arizona Territory, Dr. George E. Goodfellow examined his last patient of the day, a child. He heard the earthquake first, and thought the noise was a mining mule team passing beneath his office on the second floor of the Crystal Palace Saloon.

“This noise increased; and the building, a two-story adobe, began to shake gently, then more violently. By this time it seemed to me to be a severe whirlwind, such as frequently occurs here at this season of the year,” he wrote in a letter to Science, published on May 20, 1887.

In the saloon below, chandeliers crashed to the floor and glasses fell from shelves and shattered. The doctor picked up his patient and ran outside into a wall of noise: “When the open air was reached, the noise was like a continuous roll of heavy firing, with occasional short peals like a sharp clap of thunder.”

Geologists today estimate that the magnitude of this earthquake was 7.4, with an epicenter near the remote Mexican village of Bavispe. Twenty million people in the U.S. and Mexico would have felt that earthquake if it happened today.

Unlike California earthquakes that occur when tectonic plates bump into each other, intraplate earthquakes happen along fault lines throughout the West. These earthquakes, though rare in recent human history, created Western topography as we know it today. Earthquakes gradually pushed up the mountain ranges that run north to south and formed the wide valleys, or basins, of what geologists call the Basin and Range Province: parts of today’s Nevada, Utah, Oregon, Idaho, California, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas and Mexico.

Earth-Shattering Memories

The earthquake damaged only buildings in Tombstone, but killed in Bavispe. “At three in the afternoon, on the third of May” (a las tres de la tarde, el tres de Mayo) is a phrase Mexicans in Bavispe today repeat like a chant, remembering the stories of their grandparents.

At the church of San Miguel de Bavispe, the caretaker went outside to ring the church bell at three in the afternoon. This hourly task saved her life. At that moment, the earthquake tore the church’s Ponderosa Pine supporting beams away from the three-foot-thick walls; the roof crashed into the empty sanctuary below. The shaking lasted only two minutes, but every building quivered as solid ground turned into an ocean rising and falling with multiple waves.

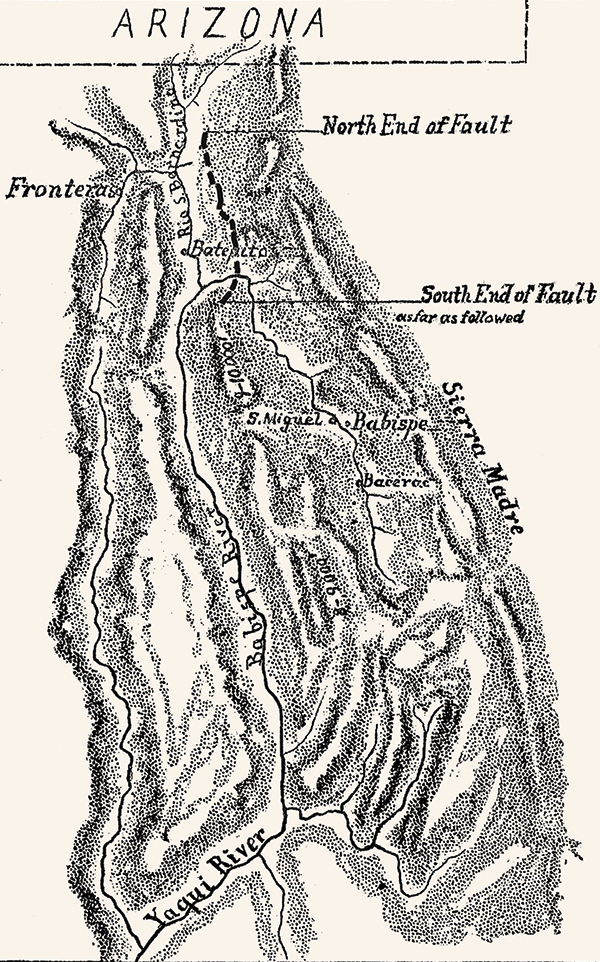

– Goodfellow photo True West Archives; Map Published in Science, August 12, 1887 –

Most of the residents were at home, resting in the heat of the day. The worst place to be was inside, beneath the viga beams that held up heavy roofs made of branches and mud. As the adobe walls shuddered, ceilings fell and killed 42 people in Bavispe. Another 27 were seriously injured. Tremors shook the roofs from almost every house, leaving 700 residents without shelter.

The force of the quake echoes through family stories in Mexico. Retired Mexican cowboy Antonio Borquez Renterria sits on his porch on a spring afternoon in 2015, gazing at the northern peaks of the Sierra Madres. Renterria’s grandfather, Manuel, was lucky to be outside of his house when the earthquake hit. Nine-year-old Manuel and his burro zig-zagged down the hill to the Bavispe River, where he planned to fill the burro’s water sacks. The violent earthquake stopped him in his tracks.

“I saw springs of water shoot up, the earth opened, the water was red from coming through the clay. It was muddy water—colorado,” Antonio’s grandfather told him.

No one in Renterria’s family died, but, he said, “we changed the way we built houses; we use different posts now to support the roof.”

Bavispe was only 90 miles south of the Arizona Territory border when the earth’s motion rang church bells in Mexico City, more than 1,200 miles south. Five hundred miles north of Bavispe, a bank’s plate glass window shattered in Albuquerque, New Mexico Territory.

The Doc Takes His Shots

Later in the summer of 1887, Clarence Dutton, of the U.S. Geological Survey, commissioned Dr. Goodfellow to go south. Joined by photographer Camillus S. “Buck” Fly, Goodfellow’s team packed their horses and headed south from Tombstone into the jagged canyons of the northern Sierra Madres, searching for the epicenter.

Fly knew of Sonora’s rugged terrain from his time photographing Geronimo’s surrender in nearby Cañon de los Embudos the year before. Dr. Goodfellow’s medical talent, honed while treating frontier gunshot wounds and mining injuries, helped him treat victims of the earthquake. He also measured the way buildings collapsed and investigated changes in topography, and Science magazine would publish his findings the next year.

– Goodfellow photo True West Archives.

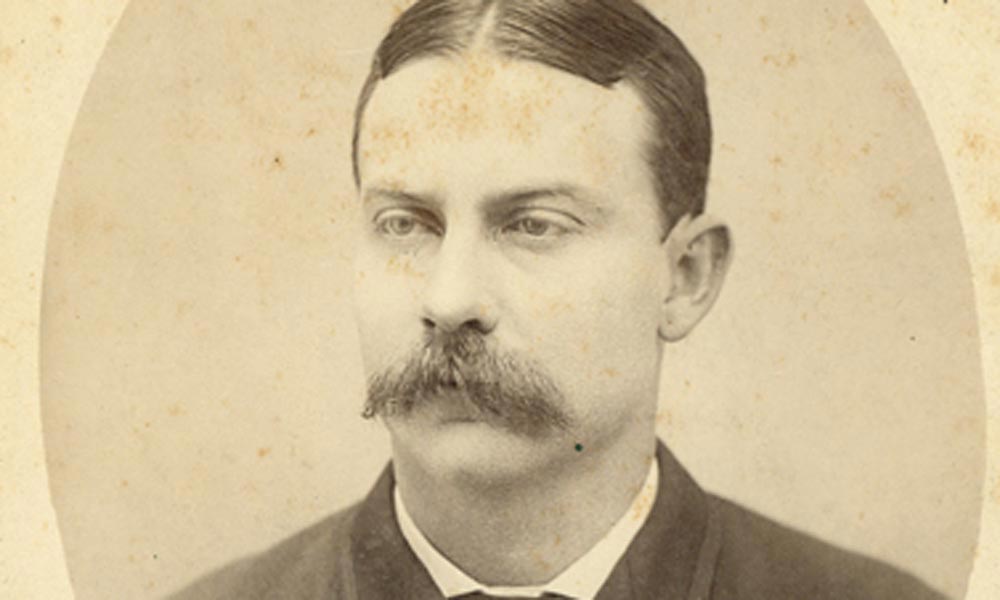

The Mexican government commissioned its own scientist to find the earthquake’s epicenter and map the geology of Sonora. Engineer José Serrano Aguilera led a team of military surveyors from the city of Hermosillo, traveling north and east over mountains where he would meet Goodfellow and Fly in Bavispe.

Goodfellow mapped a rupture that started just south of the border, near the San Bernardino Ranch, and extended south for 33 miles. The scientist found proof of the colorful stories told to Bavispe children: “Extensive evidence exists of irruption [sic] of water, sand, and fiery gases,” he wrote in his Science article, published on August 12, 1887.

He reported that mountain fires, mistaken for volcanoes, were caused by ignited gas and falling boulders that sparked against flinty rocks.

“The average offset is a little over seven feet. At Pitaicachi Peak, the slip exceeds 20 feet,” Goodfellow wrote, in a more detailed report that Science published on April 6, 1888. “It is the only known location where offset bedrock, rather than alluvium, was observed…. The appearance of the footwall of the slip in many places is a polished and striated surface, as if the same place had been the seat of similar perturbations in the past.”

Fly’s images showed total devastation in a way that Goodfellow’s scientific analysis did not. The 20-foot slip Goodfellow described is far better understood through Fly’s placement of people against what looked like a cliff; where they stood used to be 20 feet above their heads, with ocotillos shooting tall and spindly above agaves. Dropped along the fault line, the wide band of newly exposed earth demonstrated the power of the quake…and the smallness of the men.

Fly knew placing people in his shots would allow him to illustrate the earthquake’s dramatic destruction, particularly his views of Bavispe’s collapsed church, the center of life in the poor Mexican town. In addition, Fly posed seven children in front of the one structure in town that had a roof. His jarring angles of vigas over broken adobe bricks showed that the people of Bavispe hadn’t started to rebuild in the four months since the earthquake. No disaster relief organizations had come to set up tents. Nobody brought food and water. No teams of volunteers assisted in constructing what the earthquake had torn down.

The Mexican Expert

Near Bavispe, Fly and Goodfellow encountered a Mexican scientist taking measurements with his team. Engineer and geographer Aguilera had been commissioned by Mexico’s President, Porfirio Díaz, to survey the damage and scientifically document the earthquake’s effects.

Aguilera was an expert in earthquakes. In 1886, he had studied at the Smithsonian in Washington, DC, at the time of the earthquake in Charleston, South Carolina, which hit at an estimated 7.0 magnitude, caused 60 deaths and resulted in $5 million to $6 million worth of damage. President Díaz counted on him to create accurate geological maps to attract more foreign investment to Mexico’s mines.

Aguilera traveled with two military surveyors from Hermosillo over Sonora’s mountain ranges and valleys. He noted numerous new rock falls along the way. And he saw evidence of fissures filled with water near Bavispe, writing in his translated report that the “water mingled with a fine yellowish sediment,” the same sediment seen in the river 800 yards away.

– Courtesy Arizona Historical Society, PC47_B6F19_49701 –

The American team shared data with Aguilera. He now knew the exact time that the earthquake was felt at various locations in the U.S. and Mexico. The engineer calculated that the wave traveled a remarkable one mile per second between Bavispe and Tombstone, 100 miles away. Aguilera drew an intensity or isoseismal map showing the reach of the earthquake—from Mexico City, Mexico, to Albuquerque, New Mexico Territory, and from Yuma, Arizona Territory, to El Paso, Texas—about 772,000 square miles.

President Díaz’s hope of attracting foreign investors came true. In 1889, American William Cornell Green purchased Cananea, in Sonora, Mexico, and turned it into one of the richest copper mines in the world, producing 70 million tons per year. Copper ore increased in value because of its use in telephone lines beginning to stretch across the continent.

Like many on the frontier, the three earthquake explorers welcomed challenges and new experiences. Dr. Goodfellow, known as Doctor Santo—Sainted Doctor—to the people of Bavispe, received a medal from Mexico’s President for his service to rural Mexicans. Frontier photographer Fly created the first known photographs in the world of an earthquake’s rupture scarp. And Aguilera published several scientific papers in American and Mexican journals, including the first geological map of Sonora.

The earthquake dramatically changed aquifers in southern Arizona Territory, and it may have marked the beginning of today’s water crisis. Tombstone buildings shivered and cracked. In Charleston, one observer said, “The walls did a shimmy and the floor did a two-step.” Near Tucson, springs stopped flowing and wells dried up. In contrast, the earthquake immediately increased flow in the San Pedro River, wiping out stagnant malarial pools, thus saving the Mormon community of St. David from the malaria epidemic.

Last year, The New York Times and The Arizona Republic reported dangerously low water levels in Lake Mead, the reservoir that supplies Colorado River water to Arizona farms and cities. Hydrologic changes immediately after the 1887 earthquake may have been early warning signs that groundwater and surface water supplies are not infinite.

Mary Reynolds is writing a history book about the 1887 Sonoran earthquake and its hydrologic impact. She lives in Tucson, Arizona.