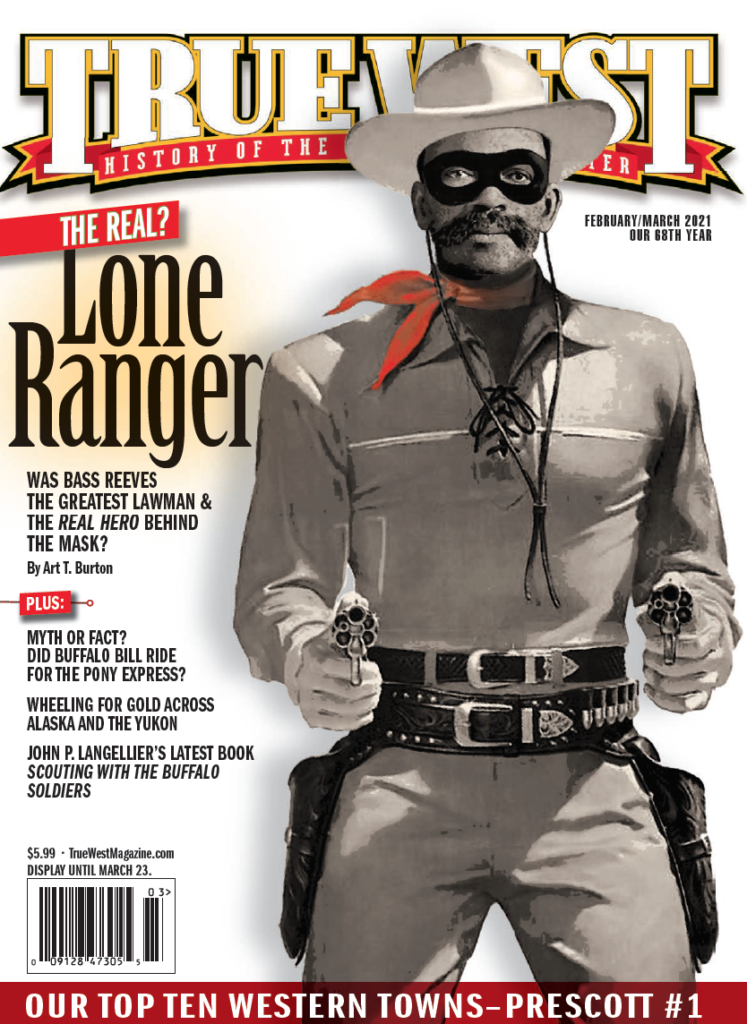

Over a century ago gold-crazed miners traded in their sleds for bikes and pedaled their way to their Alaskan bonanzas.

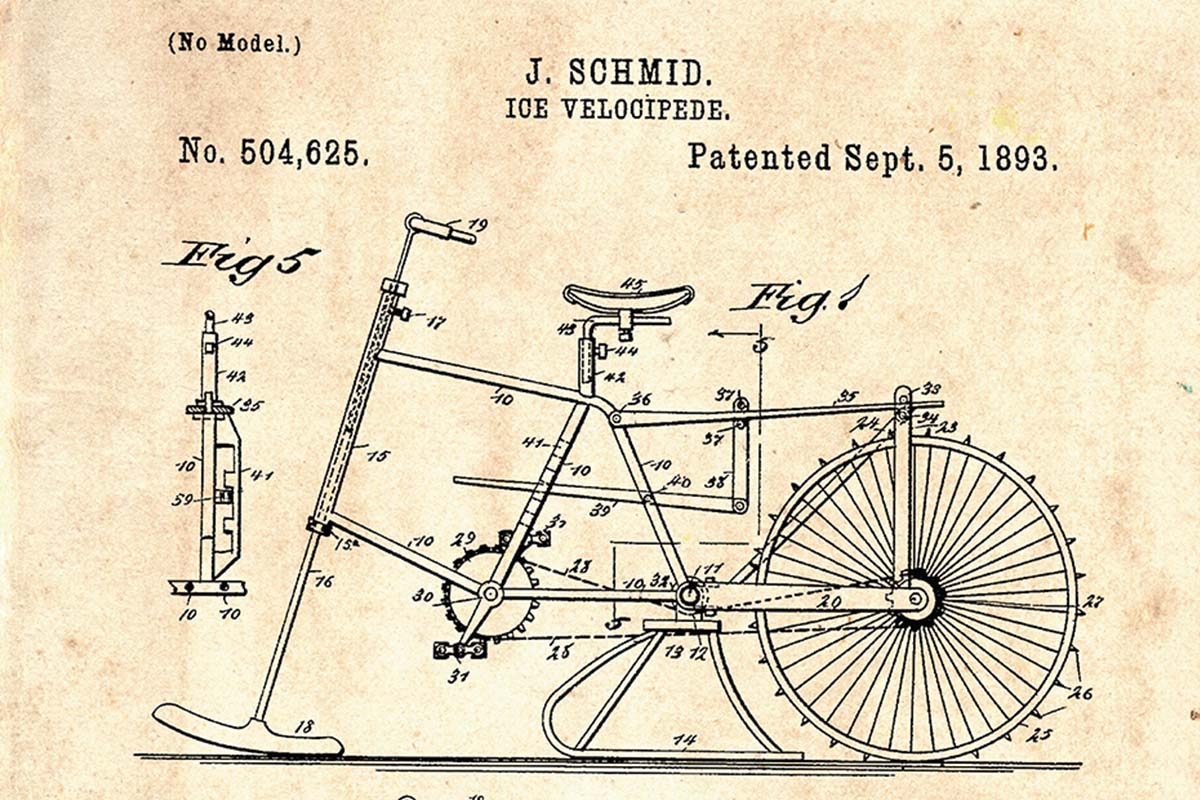

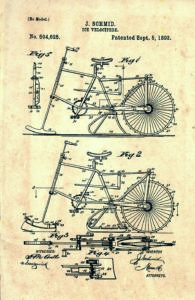

– Courtesy US Patent and Trademark Office –

In late February, as the days grow longer and supposedly milder, down-clad triathletes besting cranes and geese flock to western Alaska for The Iditarod Trail Invitational. “The world’s longest and toughest winter race,” like the eponymous mushing event, honors a roughly thousand-mile, life-saving 1925 serum run from Seward to Nome. Biking, running and skiing, pulling sleds and often pushing their vehicles (and their luck), thrill-seekers cross the Alaska Range into the meat locker interior—vales of booby-trap deadfall, snowdrifts and overflows—before sighting the Bering Strait coast.

This confederacy of pain wears its moxie and ingenuity like merit badges. But it simply follows the tracks of velocipedists who swift-footed toward precious metal when the state was a territory.

In 1897, greenhorn mobs boarded steamers bound for the Klondike goldfields while bicycles, invented 80 years earlier to counter horse shortages after the Napoleonic Wars, had become a nationwide fad. Sears, Roebuck & Company offered surprisingly modern-looking “Yukon” models for ladies and gents, and black “Buffalo Soldiers” bicycle corps patrolled the Yellowstone country, scaring horses and cows.

The cavalry officer and polar explorer Adolphus W. Greely thought this form of locomotion equal to the telegraph, perfect for quickening long-distance communication through mechanized messengers. Robert Service, the Bard of the Yukon, who missed the rush there by seven years, commuted by bike from his cabin to his Dawson bank teller job and to court his stenographer lady friend. Dr. Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes and a one-time Arctic traveler, in 1896 had endorsed the conveyance: “I believe that its use is commonly beneficial and not at all detrimental to health, except in the matter of beginners who overdo it.” Other physicians feared that, combined with sunburn, exertion and the effort to maintain balance could cause “bicycle face,” a possibly permanent condition characterized by a clenched jaw and bulging eyes. Present-day subarctic devotees, however, are more likely to blister their mugs or lose toes or ears to frostbite.

As soon as news of the bonanza broke, a New York syndicate pledged to construct a bike path to it, “a roadway, lightly constructed of steel, clamped to the sides of the mountains where it is not possible to arrange for a roadbed on a flat surface,” with a roadhouse every 50 miles, “a place of refuge wither the wheelmen, and especially the wheelwomen, can flee for safety when the elements behave badly.” The schemers proclaimed they would have nothing to do with “common methods of transport, such as railroads, boats, pack horses, dog-sleds and Indians.”

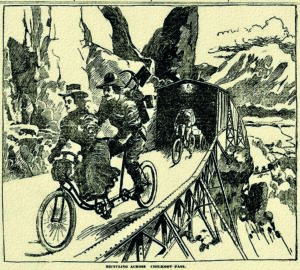

– Courtesy University of Alaska Archives –

A Palo Alto bike dealer promptly sold his inventory to drag a 90-pound sled loaded with photographic equipment across White Pass. In rough spots, he put the bicycle on the sled but made up time downhill and on ice-lidded lakes. Two of Boston’s best wheelwomen headed north, hoping to sway 1,000 female fans on their own mounts to reach Dawson with them by exercising their shapely legs. The yellow ore magnetized two youths who were biking around the world for a Chicago paper but hearing gold’s siren call, changed their course. Overcoming the lack of affordable mules, horses, oxen and even dogs in Seattle and San Francisco, inventive Klondikers beat those globetrotting kids and Bostonian “bloomer girls” on the scramble to Eldorado. Some, freshly disembarked at Skagway, grunted pedal-less contraptions with 200-pound burdens up the aptly named Dead Horse Trail to White Pass. With the required minimum of 1,000 pounds of food and 1,000 pounds of equipment, they faced 10 round-trips from sea level to about 3,000 feet.

Commercial, single-gear models were advertised as the miner’s best choice, as were snowshoe attachments clamped to the frame and bicycles with a ski instead of a front wheel. The Seattle hardware firm Spelger & Hurlbut sold merchandise obtained from Chicago’s Western Wheel Works factory. One reporter wrote that by 1900, “scarcely a steamer leaves for the North that does not carry bicycles.” The Rambler Road Wheel, which dealers touted for Alaska conditions, came with a detachable, heavy-tread tire easily repaired by “man, woman, or child.” The Klondike Bicycle, probably never built, sported solid rubber tires, weighed circa 50 pounds and, in the words of one 1897 guidebook, was designed “more for strength than appearance.” Rawhide shrunk onto its tube frame would allow prospectors to touch it without their skin sticking to steel in low temperatures. It was really a shape-shifting cart; the rider, dismounted, would haul a quarter-ton of goods on four wheels before retracting one outrigger pair and shredding back down to pick up the next load. Bikes proved to be more efficient on hard snow than on boggy, boulder-strewn summer terrain. Dawson stores hawked them to tenderfeet, and a local newspaper speculated that canine freight teams were doomed. Best of all, even a ready-made snow bike cost only a fraction of the cost of a sled or the optional dogs.

If “dog-punchers” eyed bicyclists guardedly, as they did East Coast dandies or cabin-fevered odd ducks, one can hardly blame them. Bizarre do-it-yourself arrangements flourished. Two Argonauts anticipating the Yukon River, which debouches from Lindeman Lake, had left New York with conjoined bikes from whose iron crossbars hung a rowboat that held their possessions. Winter caught up with them outside of Skagway, perhaps at “Rag Town,” a tent cluster also dubbed “Liarsville.” In March, with onions selling for a dollar and fifty cents each, a luckier soul whizzed in the opposite direction from Dawson to Skagway on an eight-day grocery run without mishaps. As the Philippine-American War flared, a bike carrier rushed headlines with the Klondike Nugget to Grand Forks, 14 miles from Dawson, and to miners on creeks close by. Catering to the men’s spiritual needs, Reverend John Jameson Wright conducted an “Evangelistic Tour,” visiting camps, pumping his legs for warmth at 40-below. With roadhouses spaced about 20 miles apart, the 400-mile Dawson-to-Whitehorse trail on the Yukon saw hundreds of wheelmen in the spring of 1901. Trading shanks’ mares for steel ponies, they’d mastered the eye-straining trick of staying in the two-inch double-track firmed up by sled runners.

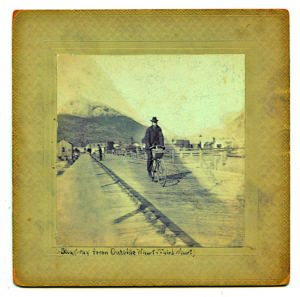

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

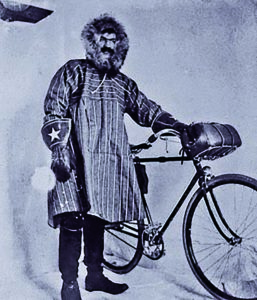

Cold-weather bikers then, too, were clotheshorses, although by necessity. Docking in Skagway, the nature writer John Burroughs noticed women in short-skirted “bicycle suits” meant to keep hemlines out of the spokes. Sears that year stocked “The Scorcher,” “The Winner” and “The Flyer.” Men wore a flannel shirt or a onesie “union suit” inside a fleece-lined overall topped by a heavy mackinaw coat or drill parka, two pairs of thick wool socks inside felt boots not so snug as to cut off circulation, plus a beaver-fur ear-flap hat, fur nose guard and fur mittens. No weight-weenies, they also might strap a fur robe or bearskin over the handlebars. The mukluks of one wore out, and his toes bruised badly on the ice. Fastened to the springs behind the seat, the canvas pannier of yet another contained a spare shirt and socks, more woolen underwear, a journal in waterproof covering, pencils and several blocks of sulfur matches. At the roadhouses, a peeling nose signaled a salty trail dog; without it, people might think you had come in by sleigh-stage.

When every claim had been staked, and scores of staked ones yielded less than they previously had or nothing at all, the action moved on. Gold strikes near Nome (in 1898) and Fairbanks (in 1902) shifted the human tide. Again, wheelmen rode cold and hard, if not always fast, taking advantage of frozen-stream highways to riches, which could be as smooth as pavement.

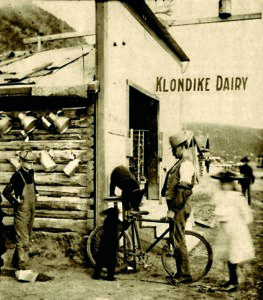

– Courtesy Beinecke Library, Yale University –

On February 22, 1900, likely ignorant of Arthur Conan Doyle’s advice, the trading post owner Ed Jesson left Dawson on an iron steed he bought for gold dust from his poke after a guy who’d just wrangled it up from Skagway sold it to the Alaska Commercial Company store. Young Ed owned a fine dog team but spent eight days taming this newfangled beast, which looked like a “white elephant” attached to his hands. He took dozens of headers into the snow, and after each one, his mutts climbed on top, nearly smothering him. “We will have to put him on the woodpile until he comes out of it,” a few old-timers commented when he’d announced his plan.

– Courtesy DeGolyer Library, SMU –

Jesson arrived in Nome five weeks later, bruised, tired and almost snow-blind. Abrasive gusts sometimes had stalled him. Fueled by mush, griddlecakes, coffee and muskrat mulligan, he had skirted open water, dodged ice jams—or head-butted them—and zipped full tilt over glare ice, overtaking a big Norwegian on skates who had been dunked. At times, kiting before the wind, he backpedaled to slow down. A small bottle of mercury at one stopover cabin froze solid, which means temperatures dipped close to 40-below. Somebody had planted a ghoulish trail marker, a red, shorthaired dog, on its nose, stiff tail straight up and paws at a trot, “like a circus clown doing his trick.”

Initially, Jesson, not yet having learned to steer with one hand and rub his numb nose with the other, vise-gripped his handlebars two-fisted. On a good day, he covered 100 miles. Sharp north winds kept him from crossing Norton Sound at the current location of a safety cabin on the Iditarod Trail, grounding him three days at a busy roadhouse. Then as now, congealed grease, frozen bearings, rock-hard “Flintstone” tires, and knee, elbow or collarbone fractures were common. Taking falls in tailwinds of 60 miles per hour, cyclists saw their transportation skid away on glassy river ice unless they’d held on. “I have ridden bucking horses and been bucked off many a time,” one of them confessed, “but I never saw a bucking horse that could get from under me as quickly as that wheel.” Temperatures drop to levels at which boiling water, tossed up, blossoms into a crystal-dust Mohawk, air pumps shatter or pedals and cranks snap. In such cold, wrenches adhere to fingertips; the knobby treads of today’s re-enactors expire spontaneously. One single-speed demon in 1908 had so many flats that he stuffed rope into his tires to make it home. On his 1,000-mile journey, Jesson carved wooden replacement pedals, each of which lasted only a day. After buying nuts and bolts, he hacked a more durable one out of sheet metal, helped by a missionary. Still, he praised his boneshaker. “It didn’t eat anything, and I didn’t have to cook dog feed for it.”

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

Starting in March of the same year as Jesson, Max Hirshberg raced spring’s thaw from Dawson to Nome, where people stole tents and moved houses while the owners were out prospecting. His departure had been delayed by blood poisoning—fighting a hotel fire, he’d stepped on a rusty nail. Drivers of dog teams he approached en route veered off-trail and restrained their barking packs from nipping his heels. (Fellow ice-roadies, meeting mushers at blind corners head-on, created snow angels or augered into berms.)

– Courtesy Alaska and Polar Regions Collections, Elmer E. Rasmuson Library, University of Alaska Fairbanks–

Near trip’s end, Hirshberg fell through ice on the Shaktoolik River and almost drowned. Struggling two hours through ice-cubed water, he lost his watch and a gold poke worth $1,500 but managed to save his bike. When he got marooned on a sea-ice floe, he jumped to shore, grabbed a driftwood log and, like an overdressed gondolier, poled his ride back to terra firma. Just east of Nome, Hirshberg crashed and busted his chain. Unable to pedal or brake, he threaded a stick through his mackinaw coat for an improvised sail. For once, the wind blew from the right quarter, yet it forced him at times to steer into snowdrifts to stop his wild flight.

He’d turned 20 during his adventure.

– Courtesy of National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Yeomans Collection, KLGO 58599 –

The last of 1900’s spring stampeders, the sea captain John Sutherland, rolled into Nome overdue and presumed dead, 62 days after hightailing out of Dawson. When he first glimpsed Norton Sound, the ice had already gone out. So, he walked his bike, detouring 360 miles through swamps with mosquitoes roiling like smoke. The bike frightened some Athabaskans who shot at Sutherland, because their shaman said all the fish would die if they didn’t kill him. Fortunately, soldiers from Fort Saint Michael came to his rescue. The next day, the Indians brought peace offerings and punched the Scotsman to see if he was real. One tried to buy his magic hoops. Twenty pounds lighter than before, Sutherland tipped the scales at 230, regardless. “I rode my bicycle night and day,” he said, and “well, sometimes it rode me.”

While two-wheeled traffic may have irked grizzled Yukoners, the transplants’ progressive antics intrigued Native spectators, always drawing crowds. “White man he sit down, walk like hell,” one quipped when, showing off, Ed Jesson encircled a camp. Others, hollering “Mush!”—the traditional dog handler’s command—urged the passing figure to accelerate.

Hardy women and men still get to roadless Nome by parking their butts, though they shun the heated sno-go (snowmachine) or cushy airliner seats. With their snotsicles and waxy cheeks, breath plumes and hulking silhouettes, they may resemble Team Donner or Scott’s doomed Antarctic expedition. But what is transport for some, for others is mettlesome sport: a personal challenge and homage to pioneer grit.

Michael Engelhard is the author of Ice Bear: The Cultural History of an Arctic Icon. As a non-driving cabin dweller on the fringe of Fairbanks, in interior Alaska, he has done his share of winter biking.