The Earps’ last stand in Los Angeles was more bust than bonanza.

In 1866 the first home for disabled war veterans was opened in Togus, Maine, and not long thereafter, more veterans homes opened in various locations around the Midwest and Eastern United States. By the mid-1880s, the need for a comparable home on the West Coast was recognized, and the search was on. In 1875, Santa Monica, California, had been founded, and the first private residences were sold there. Future Tombstone, Arizona/Earp icon, the “silver-tongued orator,” and legendary Earp O.K. Corral defense attorney, Thomas Fitch, was on hand as the featured speaker at the July 1875 city launch party. In the 1890s, another Tombstone notable, Tombstone Weekly Epitaph newspaper owner/editor, and tourist promoter, S.C. Bagg, would become an active participant in the home sales there.

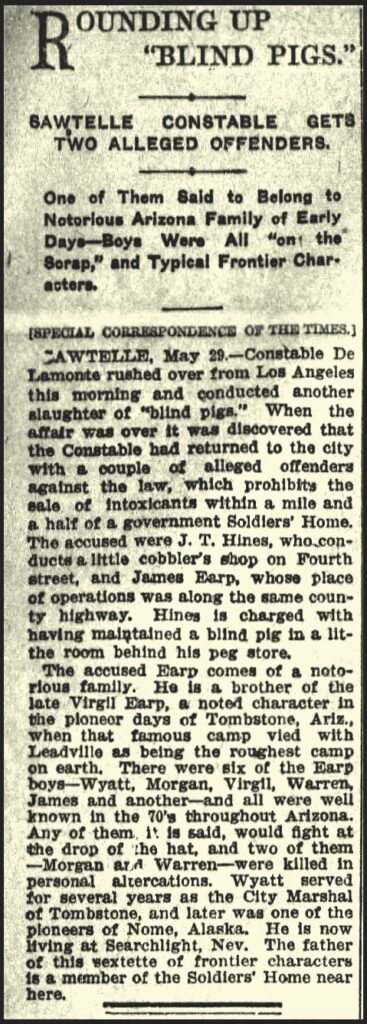

There was vast open space between the cities of Los Angeles and Santa Monica, and in 1888, after intense negotiations, a property deed was recorded, and construction initiated on a new “Pacific Branch (of the) National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, Los Angeles County, California” (aka the “Old Soldiers’ Home”) about three miles east of Santa Monica, and 12 miles west of Los Angeles. In 1897, the first lot was sold in the newly developing town of Sawtelle, which abutted the Soldiers’ Home. Many veterans and their families purchased land in Sawtelle to be near relatives living there. The problem was the sale of alcohol was prohibited by law within three miles of the Soldiers’ Home.

The Earps Invade

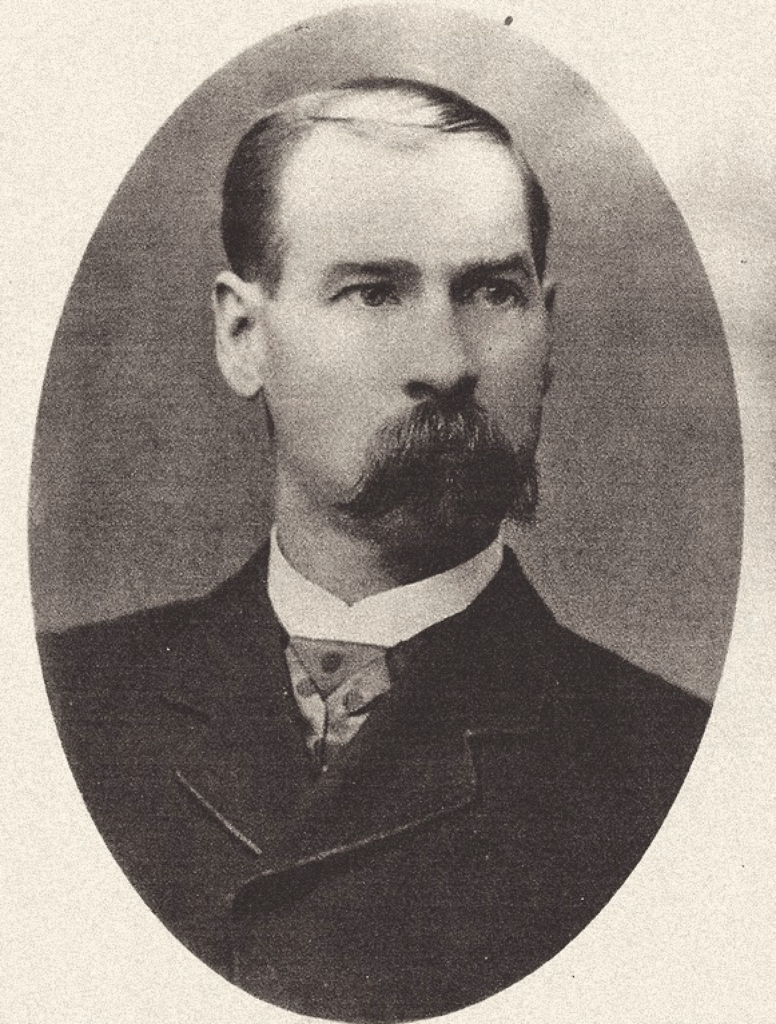

Enter the Earp family in the first decade of the 20th century, with their illicit gambling and alcohol sales (aka “Blind Pig”/bootlegging) scheme and lifelong experiences as law officers, saloon and brothel owners/operators and professional gamblers. It was their final attempt together, as a family, to obtain the big profits they had been pursuing about the country their entire lives. The newly emerging Santa Monica–Sawtelle area was to be their final shot at a major bonanza, and it would involve all the surviving members of the Earp family, including their patriarch, Nicholas.

Blind Pigs, Sunshine and Santa Monica

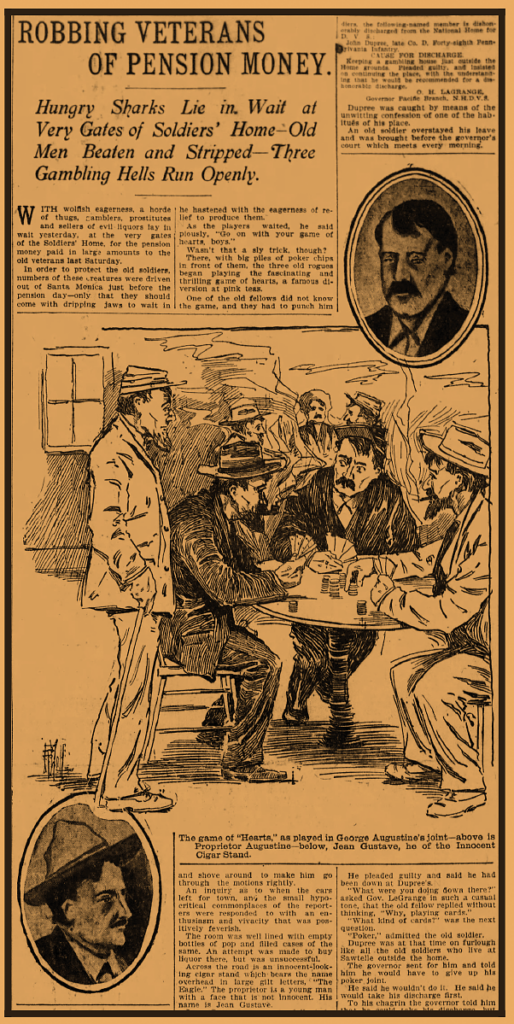

The local newspapers frequently stated that evil men were standing at the gates of the Soldiers’ Home, taking advantage of these veterans, grabbing their pension money. The reality was that the veterans enjoyed going into Sawtelle and having a good time. Furthermore, many of the “villains” castigated by the press were veterans. Some of the leading “entertainment providers” in Sawtelle were James Earp, John Dupree and P. J. Flynn. All three were Civil War veterans, residents of Sawtelle, and in good standing with their Soldiers’ Home buddies. Some, like James Earp, even had relatives living in the Home.

The Sawtelle area Soldiers’ Home differed in many ways from other institutions for veterans. The population was huge, it was of recent origin and the community adjacent to it only came into existence because of the Home. And, in an unusual development, those individuals most involved in organizing the card rooms, blind pigs and whorehouses were themselves veterans, residents either of the Home or of nearby Sawtelle.

The Soldiers’ Home, Pacific Branch, became a tourist site, well positioned on the famous Balloon Route, the interurban that took passengers from Los Angeles locations to Santa Monica, with a stop along the way to pose with military-clothed veterans at various Home buildings.

In this era, the Soldiers’ Home was well-known nationally, praised for its fine buildings, extensive grounds, gardens and farm, and for its efficient hospital and other facilities. A typical instance of the far-and-wide impact of the Home occurred in 1913, when the Arizona Republican reported that Civil War veteran Elias N. Pegg had just left Arizona for the Home in Sawtelle, for an eye operation, journeying the long distance due its reputation for exceptional medical care.

The Home was frequently featured in photographs carried in the local press as well as in regional and national magazines. This important institution, though, was adjacent to Sawtelle, which led to the following assertion in the California Journal of Assembly:

“The most pitiful sight in all the southland today is not the soldiers’ home, a splendid series of fine mansions surrounded by a magnificent park and beautiful gardens, but the town of Sawtelle beside it, where many of the wives and daughters of the old, well-cared for veterans eke out a miserable existence in old shacks and tumble-down structures, taking in washing for a living, or running blind pigs and otherwise ministering to the animal desires of some of the male pigs, some of these same old favored wards of the nation.”

Tumbling Dice in Sawtelle

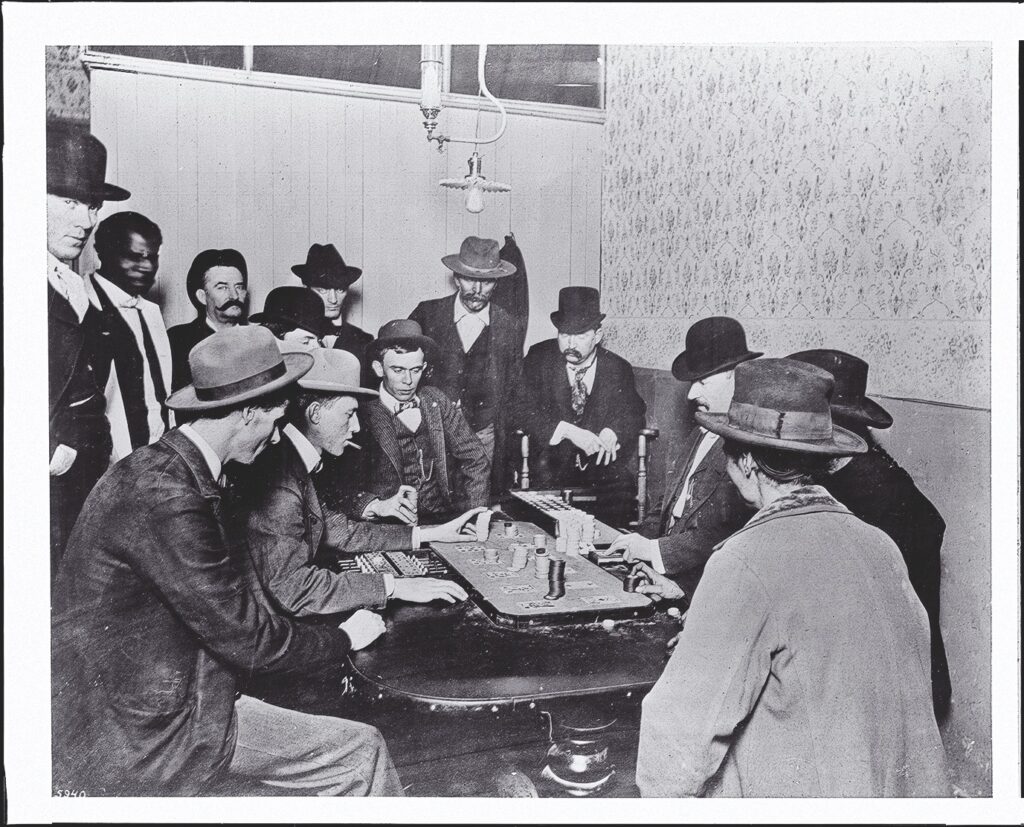

The “battle of Sawtelle” was not a street fight, nor a man-on-man duel with drawn revolvers. The newspapers, though, almost every time an Earp was mentioned, used words like “notorious” and “gunfighter,” and peppered most stories with references to Tombstone and other examples of frontier violence. The battle, for the Earps, was to see how big a slice of the huge federal pension fund could come their way. Many were in on the game, and the Earps hoped that their decades of prowling the mining boomtowns of the West, operating the card games, whorehouses and saloons, as well as often being cloaked with authority as lawmen and justices, would give them an edge in the environment of Sawtelle, where thousands of veterans were bored and thirsty and had some spare pension money to take care of these problems.

As a reminder of what was at stake, in the fiscal year 1908, which had ended a few months previously, $567,985 was distributed to Home veterans, most receiving between $6 and $20 a month. This was a lot of money, and certain operators in Sawtelle determined that it shouldn’t go farther than the card rooms and blind pigs of Fourth Street.

Nicholas was most likely the cause of the move to Sawtelle by the Earps. He and James had to have had that conversation, because shortly after James moved from San Francisco to Sawtelle, Nick was enrolled in the Soldiers’ Home. “Justice Earp” was probably one of the best known of the thousand-plus veterans in the Home, and his forceful, outgoing manner must have been important in shifting clientele toward the Fourth Street card room of his son James.

James knew that he could count on Nicholas, and to a lesser extent,

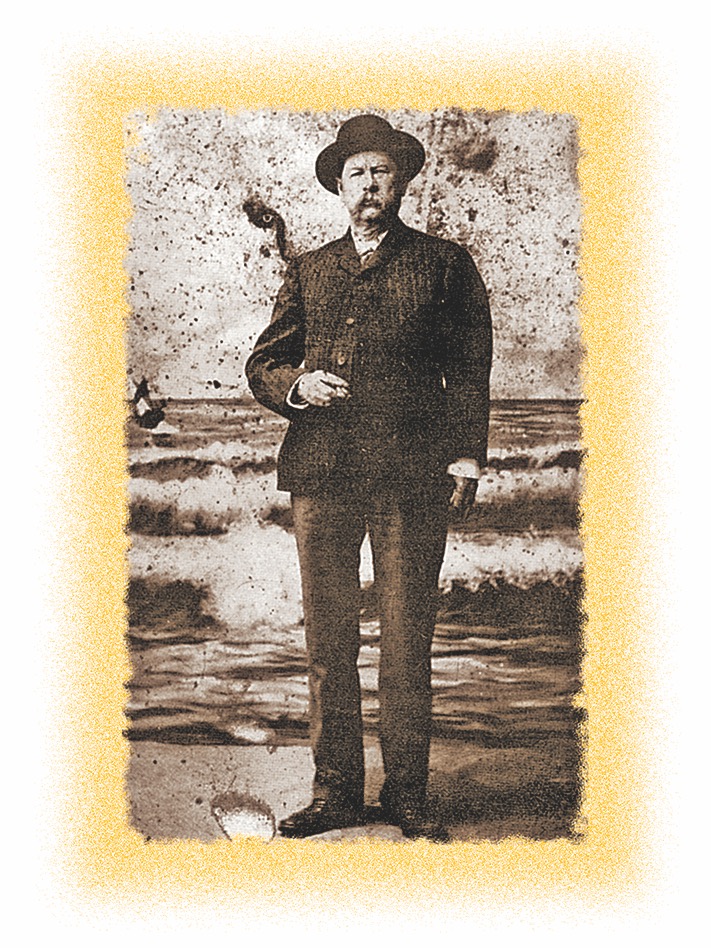

his older half-brother Newton, “on the inside,” to steer traffic toward his Fourth Street venue. For a year or so Virgil had lent his presence and his name toward the Sawtelle purse, but then he had moved on to Nevada, leaving James to head the Earp interests. Virgil’s death in 1905 was not only a blow to the Earp family but meant that there would be no return to Sawtelle for him. Shortly after this, James was arrested as drunk and disorderly in downtown Los Angeles. The following year, in May 1906, he was arrested in a major raid on Sawtelle blind pigs.

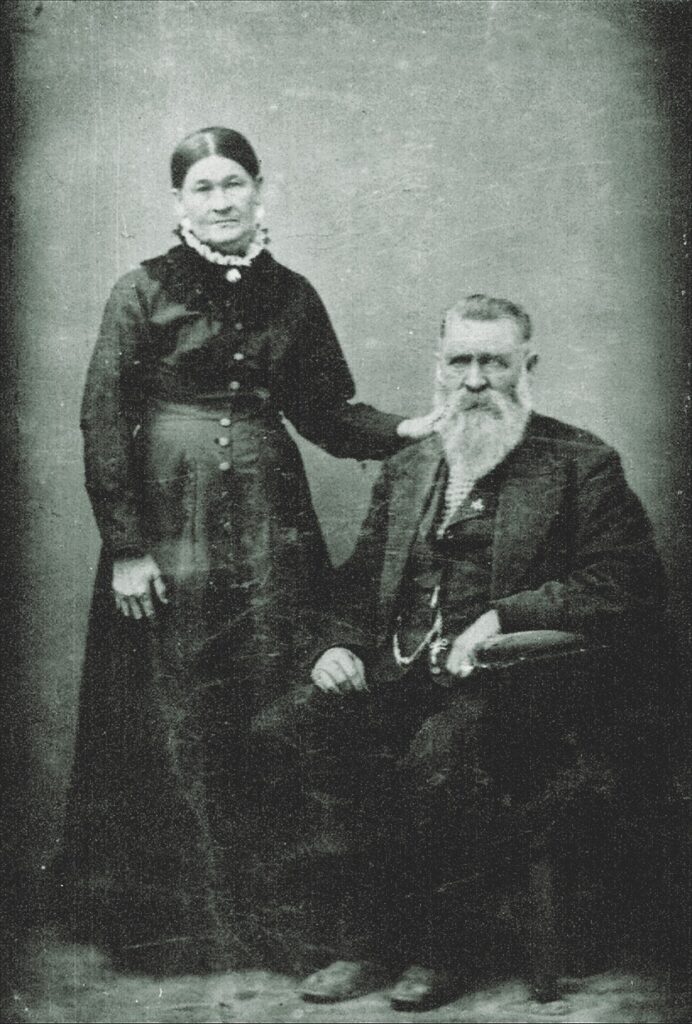

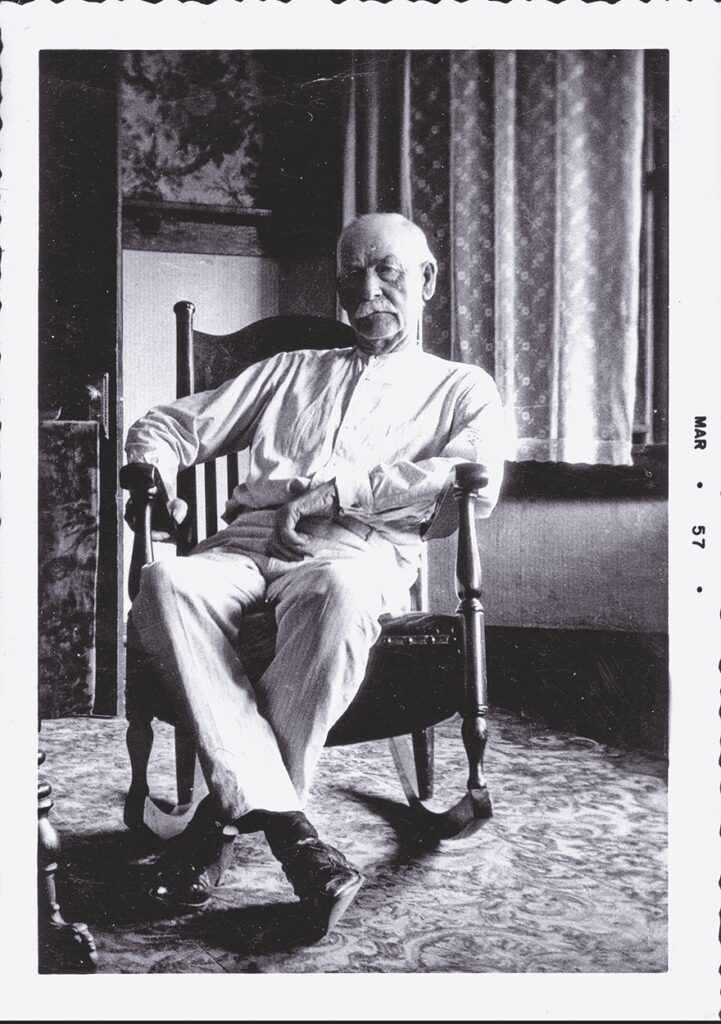

Further serious problems loomed. Inside the Home, Nicholas was deteriorating. The old fellow had been born in North Carolina in 1818 and was almost 90 years old. The letters to the Pioneer Society in San Bernardino had lessened, as did visits to the Home from his old contacts in Colton and San Bernardino. He was placed in the Home hospital. Judge Earp was “near death.”

The end came for Nicholas Porter Earp on February 12, when “arterial sclerosis” proved too much for the father of the Earp boys. There were quite a few obituaries or at least death notices for Nicholas P. Earp, especially in the press of California and Arizona. A typical report appeared in the Santa Monica Outlook of February 14, stating that he was considered an “esteemed exemplary member by his associates both in barrack and later in the hospital.” And, being polite and not mentioning blind pigs, the Outlook mentioned that “one son, James Earp, lives in Sawtelle, near the home.” Too bad that about Wyatt, they wrote, “another, Nathan, is in the Searchlight mining district.”

Brother James’s Last Stand

Seemingly, James Earp adjusted well to his new life in Sawtelle. After returning from Nome with Wyatt, he headed to San Francisco, while Wyatt opted to open a saloon in Tonopah, Nevada. In 1901, though, James shifted his pension payments to Sawtelle, as he had decided to throw in his lot with that community, knowing his father Nicholas, and brother Newton, intended to move to the Soldiers’ Home.

Although his specific location is not known when Wyatt visited him in Sawtelle in 1903, James was declared “the veteran club man of North Fourth street.” As maps of Sawtelle indicate, this was the “gaming” part of town. Those of us familiar with father Nicholas’s personality don’t need documentation to accept that Nick would encourage his fellow veterans to “stop in and say hello to Jimmie” on the way into town.

Nick and his boys were tight as glue, and the first few years he was in the Soldiers’ Home, Nick was in his usual self-assertive role; he needed to be noticed. As soon as he was enrolled in the Home, he was appointed a delegate to the Los Angeles County Democratic Convention. His letters to the Pioneer Society were usually reprinted in the San Bernardino Sun; he was former president of the group. This is the kind of fellow on the Home “inside” that we can conclude was pushing Jim Earp’s whiskey and card activities in Sawtelle.

Wyatt and Virgil visited Los Angeles with their wives several times during this era. Sometimes they were hosted by brother James, and a few newspaper notices indicated that they also went to the Hollenbeck Hotel. The Hollenbeck was owned and operated by their former Tombstone acquaintance and staunch ally, Albert Clay (A.C.; “Chris”) Bilicke, who had owned Tombstone’s Cosmopolitan Hotel along with his father Carl Gustave “Gus” Bilicke. Bilicke had backed the Earp brothers after their legendary O.K. Corral gunfight, testifying at the Spicer hearings that Tom McLaury appeared to have a gun visible in his pants pocket just prior to the altercation.

Virgil spent a significant amount of time in Sawtelle in 1902 and 1903. The Earps had an especially fine reunion in Los Angeles in 1903, where Bilicke entertained many of the family members. He even made a special effort to go and collect Nicholas from the Home, so he could join Wyatt, James, Virgil and their wives, as well as sister Adelia and her husband. It is also most likely that Newton was part of the get-together. Adelia praised the doings of Bilicke, who had set aside “a comfortable green room” for the occasion. The tenor of the meeting can be gathered from Adelia’s report of Virgil’s booming voice, “Deelie, pour some coffee now, and put some of that there whiskey in.”

Where Was Wyatt?

On September 6, 1903, the Herald published a letter critical of the Earps, in particular of Wyatt Earp. The phrase “Bad Man of Other Days” was part of the headline, and the article included absurd Earp doings in Dawson and other Klondike places that no Earp had ever known.

In response, in the Herald edition of September 9, George W. Parsons vigorously defended the Earps, ridiculing the “bad men” usage, and pointing out that the Earps had been peace officers “defending and enforcing the law in the face of death.” Parsons had known the Earps in Tombstone, had ridden in posses with them, and was still in contact with the family.

This incident was clarified in the Parsons diary entry of September 19, 1903, when he wrote that he had a “good swim at Santa Monica.” He also met with Wyatt Earp, who “thanked me for my defense of him. He has killed a few, but they ought to have been killed & he did a good job.” This information from Parsons suggests that Wyatt Earp was in the environs of Santa Monica and Sawtelle on a visit to his dad and brothers James, Virgil and Newton.

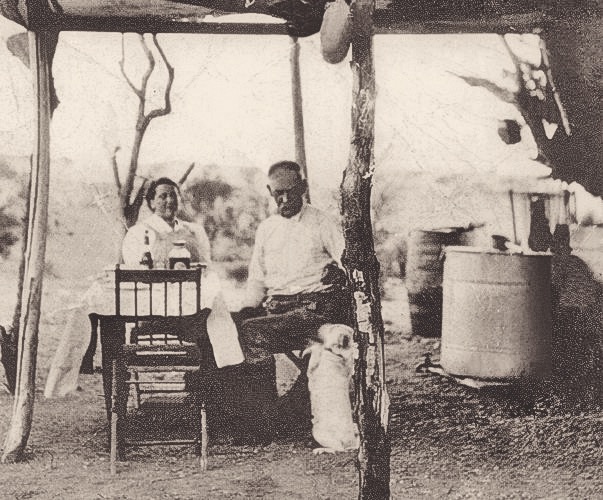

There was never any indication that Wyatt was interested in having any role in the Sawtelle operations. He and other investors had opened a Nevada saloon, the Northern, on February 8, 1902. He seemingly did everything right, brought in new bar equipment, and advertised in the appropriately named newspaper, the Tonopah Bonanza. The Northern was two buildings away from the Miners Exchange Hall. Wyatt’s hopes had been so high that he had even planned a stage line between Tonopah and Ray. Few things, though, worked out well for Wyatt and Josie in Tonopah. In fact, Josie spent most of her “Nevada time” visiting with her relatives in Oakland and San Francisco.

Wyatt not only failed in Tonopah, but he quit Nevada and shifted to Arizona Territory. He opted for the near-desert, and he was soon in Cibola in Yuma County, running a small ranch. This was some miles southwest of Quartzsite, Arizona, and in November 1904, Wyatt was elected the local constable with fewer than a dozen votes cast. Ranching was boring, and by mid-1905 Wyatt was in the Whipple Mountains working a copper claim in the fall, winter and spring months, living in various locations about Los Angeles in the summer. Mining would occupy most of his time until his death on January 13, 1929.

In 1906, while living at the Hampden Arms Hotel in Los Angeles, Wyatt met a young John H. Flood, who would become a loyal friend, and have a huge influence throughout rest of his life (and thereafter), and his wife Josie’s, until her own death in 1944. Flood attempted to write Wyatt’s biography for publication. The attempt failed but did eventually lead to Stuart Lake’s seminal 1931 book Wyatt Earp Frontier Marshal, published shortly after Wyatt’s death. Lake’s book, along with Walter Noble Burns’s 1927 classic Tombstone: An Iliad of the Southwest, were the basis for subsequent Hollywood Earp movies, including 1993’s influential Tombstone. It was also John Flood (who died in 1958) who, in the early 1950s, was tracked down by tenacious historian/collector John Gilchriese, and subsequently passed on to him many firsthand stories of Wyatt and the Earps, and many of Wyatt and Josie’s personal possessions and letters. Many of these are currently in the collection of author David De Haas.

By 1905, 3,200 members were reportedly living in the Sawtelle Soldiers’ Home.

On October 19 of that same year, Virgil died of pneumonia in Goldfield, Nevada. On February 12, 1907, Nicholas Earp died in the Soldiers’ Home hospital and was buried in the adjacent cemetery (currently known as the Los Angeles National Cemetery); and in 1908, James Earp appears to have been living once more in the San Bernardino area of Southern California. In 1909, brother Newton Earp moved to Oakland, (Northern) California, to live with his daughter Alice, effectively ending the legendary fighting Earp family’s final endeavor together—bootlegging Los Angeles, Santa Monica and the Old Soldiers’ Home.

Don Chaput is a well published author, including Virgil Earp: Western Peace Officer. David D. De Haas, M.D., is a retired emergency medicine doctor who has published many medical and Wild West-related articles.

“Tumbling Dice, Blind Pigs and Brothels: The Earps’ last stand in Los Angeles was more bust than bonanza” is an adapted excerpt from Don Chaput and David D. De Haas’s The Earps Invade Southern California: Bootlegging Los Angeles, Santa Monica and the Old Soldiers’ Home (University of North Texas Press, 2020).