— Powder Horn photo courtesy Jack Caffall —

Undeniably the darkest hour in Texas’s history, the Reconstruction era, between 1865 and 1877, turned the Lone Star State into a bloody and dangerous place.

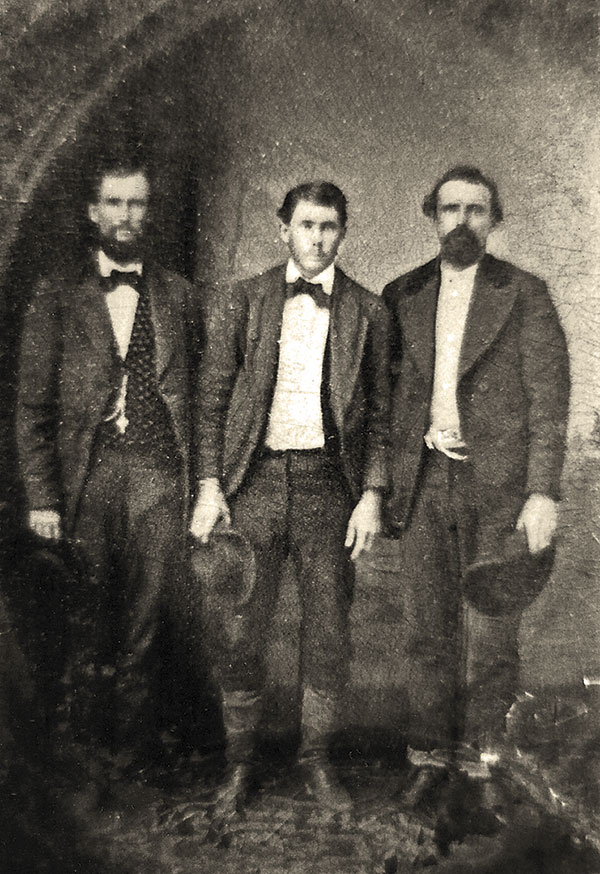

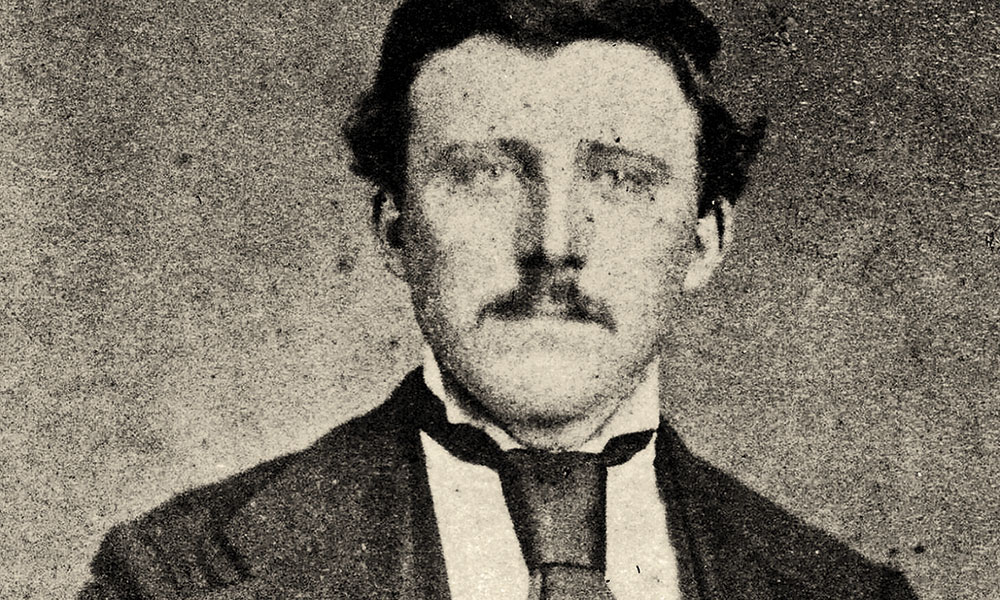

Lawmen of this era were reflective of the society that they served. John Jackson Helm’s story is a prime example of those law officers who operated on the fringes of the law.

During the Civil War, Helm fought briefly for the Confederacy. Following the war, he assisted Capt. C.S. Bell in tracking down members of the Taylor Gang during what scholars refer to as the Sutton-Taylor Feud.

As an officer of the law, Helm served the cause of “justice” by using tactics just as infamous as those practiced by the men he pursued.

Helm’s actions against the Taylors would come back to haunt him.

— Creed Family photo Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection —

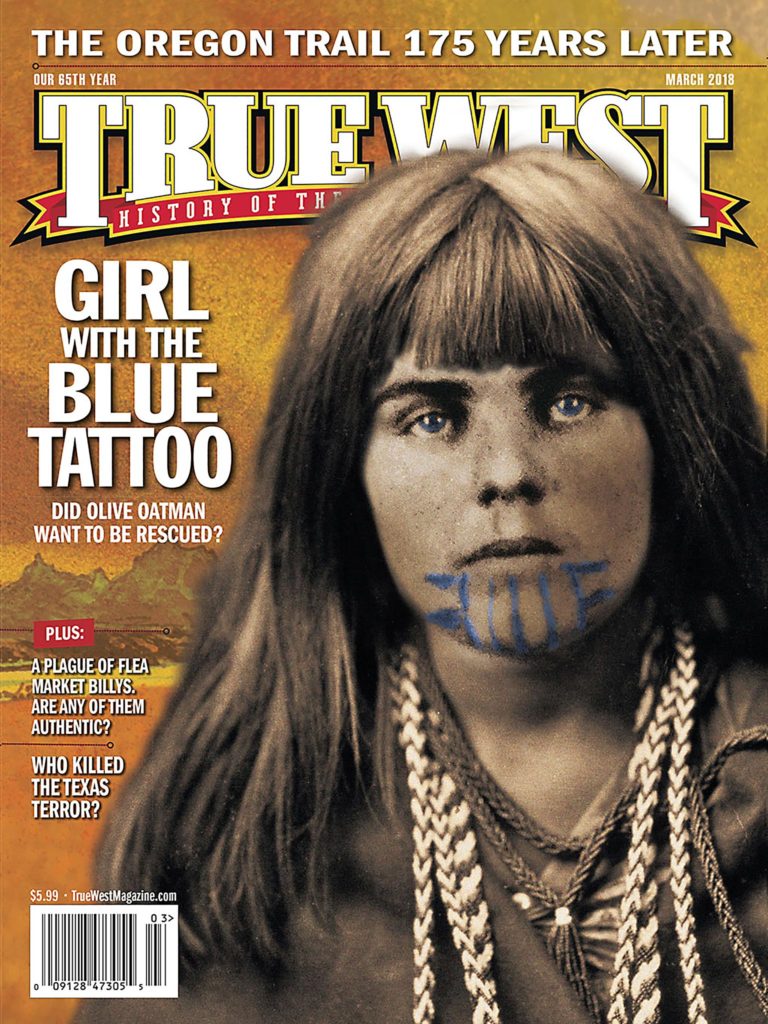

The Terror of the Country

Creed Taylor, a former Texas Ranger and Confederate soldier, wrote with bitterness that Helm “was not a mechanical genius and never invented anything outside of plans to murder innocent men.”

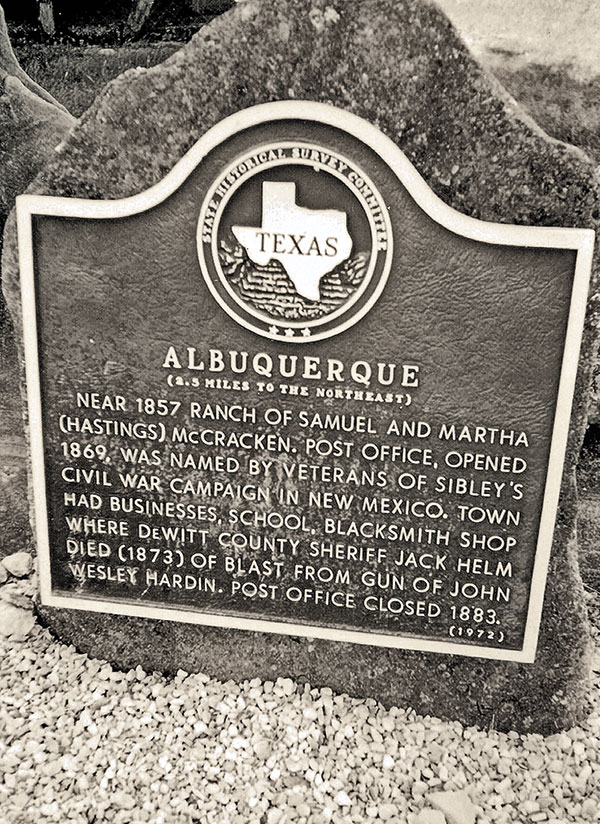

But during the early days of Albuquerque in Gonzales County, Texas, in 1873, Helm was known as an inventor, working away at John Bland’s blacksmith shop on his improved cultivator and his cotton worm destroyer, which both received patents that year. The first improved the eveners that connected a pair of cultivators. The second allowed a team of mules to draw a moveable frame that straddled the rows of cotton, sweeping the worms from the plants and crushing them on the ground.

As the DeWitt County sheriff, Helm had plenty of enemies who wished him harm. Yet he considered himself among friends whenever he worked on his inventions in Albuquerque, so he would leave his gun belt and pistols hanging on the hall tree at Samuel L. McCracken Sr.’s boardinghouse, where Helm sometimes stayed. He wasn’t completely careless. He did carry his bowie knife, an essential tool that would not interfere with his work in the blacksmith shop.

— All images Courtesy Chuck Parsons Collection Unless Otherwise Noted —

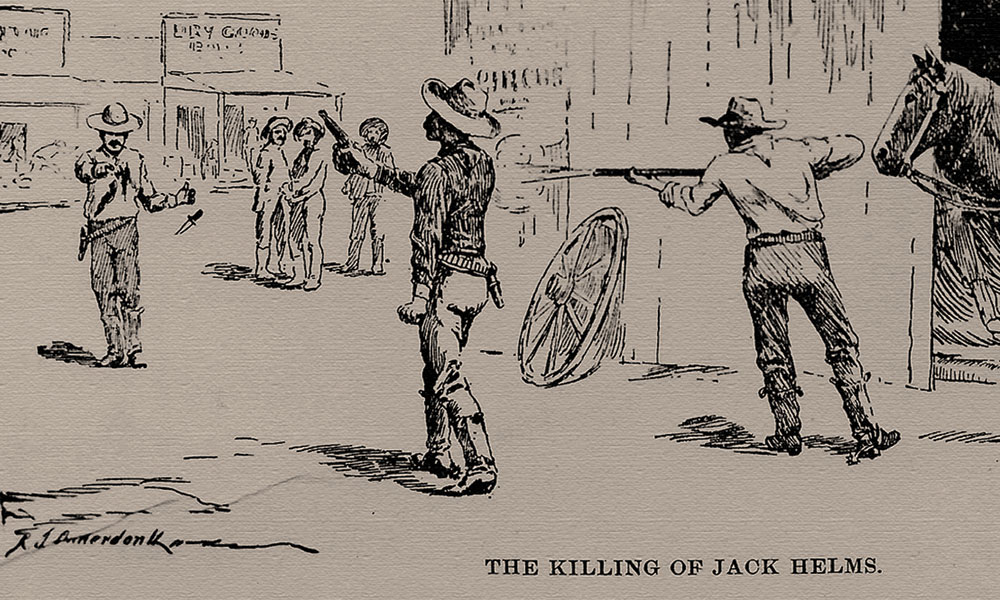

On July 18, John Wesley Hardin “went to a blacksmith shop and had my horse shod,” he recalled, more than two decades later. “I paid for the shoeing and was fixing to leave when I heard Helms’ [sic] voice: ‘Hand up, you d—s—of a b—.’”

Hardin looked around and saw Helm “advancing” on Creed’s nephew, Jim Taylor, with the large knife in his hands. Then someone shouted, “Shoot the damn scoundrel!” but Hardin gave no indication who should shoot or who was the scoundrel. Hardin or Helm?

In Hardin’s mind, the scoundrel who needed killing was clearly Helm, and he was taking no chances. “So I grabbed my shotgun and fired at Capt. Jack Helms [sic] as he was closing with Jim Taylor” is how Hardin relived the dramatic exchange, making it clear that the shotgun was his, not Helm’s.

He then pointed his shotgun at the Helm crowd and ordered them not to interfere. “In the meantime,” Hardin stated, “Jim Taylor had shot Helms [sic] repeatedly in the head, so thus [did] the leader of the vigilant committee, the sheriff of DeWitt, the terror of the country, whose name was a horror to all law-abiding citizens, meet his death. He fell with twelve buckshot in his breast and several six-shooter balls in his head.”

Who Shot the Sheriff Dead?

Helm’s final moments on July 18 remain controversial. A number of people observed what actions transpired, but they provided conflicting reports. The salient point of agreement is that Helm was killed that day—Hardin mistakenly recalled the date as May 17, but a Gonzales Index newspaper account confirmed July 18—while the controversy remains: Who should receive credit for the killing?

McCracken told the Gonzales Index that he, Helm and Hardin “were sitting engaged in friendly conversation” when a stranger rode up. He dismounted and “walking up behind Helm attempted to shoot him,” but the stranger’s pistol failed to fire. Of course, Helm, surprised, as certainly were the others, turned around; now the stranger’s pistol did work, and as Helm stood up, he shot again, the bullet wounding Helm in the breast.

Helm, no coward now, at the same time rushed at him, attempting to take away his pistol, grappling with him. Just at this moment, Hardin fired at Helm with his double-barreled shotgun, shattering his arm. Helm, now dying on his feet and fully realizing the deadly situation, turned to escape into the blacksmith shop, but the stranger pursued him, shooting him five times about the head and face.

Hardin and the stranger “then mounted their horses and rode away together, remarking that they had accomplished what they had come to do,” reported the Bastrop Advertiser on August 2, reprinting an undated article from the Gonzales Index.

The stranger, of course—not identified in any contemporary source—was Jim Taylor. He wanted the “right” to kill Helm as he considered Helm responsible for the death of his father, Pitkin Barnes Taylor, shot from ambush in late 1872. Jim considered Bill Sutton equally responsible for killing his father, but that act of vengeance would have to wait.

From the available contemporary sources, one must accept that Jim deserves the credit for killing Helm, with Hardin assisting. Jim, putting four or five bullets in Helm’s head, did the killing damage. Yet the Gonzales newspaper editor concluded his report with a statement that leaves us wondering: “We heard of no cause of quarrel between Helm and the parties who killed him.”

The editor certainly knew who Hardin was, although he claimed to be unaware of any reason for the quarrel leading to Helm’s death. Victor M. Rose began writing his history of the Sutton-Taylor Feud in 1880. Some of what he wrote was from memory; of the Helm killing, he wrote, perhaps without checking his files reporting the event: “two young men supposed to have been friends of the Taylors, rode up to the shop and announced through the throats of their revolvers the implacable message of fate.”

— Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection —

The Best Act of Hardin’s Life

Helm’s death did not mark the end of the Sutton-Taylor Feud. In March 1874, eight months after his death, the hatred between the Taylors and Suttons still raged. On March 11, Jim and his cousin Bill caught up with their enemy, Bill Sutton. Jim shot Sutton to death while cousin Bill shot companion “Gabe” Slaughter to death on the deck of the steamer Clinton in the Indianola harbor. Hardin was not there, but may have participated in the planning of the double killing.

The deaths of Sutton and Slaughter resulted in such negative press concerning the lawlessness in south Texas that Gov. Richard Coke sent a troop of Texas Rangers to DeWitt County to settle the feud. Captain Leander H. McNelly had 30 men under his command; he had been a former captain in the state police, as was Helm. McNelly’s presence didn’t end the feud, but he did prevent any serious battles while he was stationed there.

One of McNelly’s Rangers, T.C. Robinson, under the pseudonym of “Pidge,” wrote a letter on November 8, 1874, to Austin’s Daily Democratic Statesman, that stated: “…Capt. Jack Helm, who kept his helm hard down on the people of this section, until Wes [Hardin] one day, in a playful mood, gave him a broadside and sunk him.”

Even among those who may have seen Jim empty his pistol in Helm’s head generally considered that Hardin deserved the credit for killing Helm. Apparently Pidge was unconcerned or perhaps unaware of Jim’s involvement in the killing.

Hardin recalled that the shooting “happened in the midst of [Helm’s] own friends and advisors” who did nothing to help Helm, but “stood by utterly amazed.” He then added: “The news soon spread that I had killed Jack Helm and I received many letters of thanks from the widows of the men he had cruelly put to death. Many of the best citizens of Gonzales and DeWitt counties patted me on the back and told me that was the best act of my life.”

One is left to wonder just how many congratulatory letters Hardin received for killing Helm, as none have survived.

Jim was killed in 1875 by a posse that included deputies of the late Sheriff Helm. He could not present his version of how he had avenged the death of his father, but in 1894, with many of the feudists dead, Hardin could, and did.

Helm’s Tarnished Legacy

In March 1874, Gov. Coke sent Adj. Gen. William Steele to investigate the killings. It may have come as a surprise to the governor, in opening Steele’s report, to read: “I find that the present state of violence had its origin in the operations of Jack Helm, a sheriff appointed by Gen’l J.J. Reynolds, and afterwards made Capt. of State police under Gov. Davis.”

Steele explained: “From the statements made to me it appears to have only been necessary for a man should be pointed out to Helm as a cattle thief or a ‘bad man’ to have been arrested & started off to Helena for trial by Court Martial, but the greater portion of those that started for Helena never reached that point but were reported as, escaped, though never heard of since.

“In one case, two young men by the name of Kelly were started to be returned to Lavaca County, but were killed by the guard, one of whom was Wm. Sutton (whose name now designates one of the contending parties) who was with others tried & acquitted—a verdict which is not believed to be just, the fears of the jurors or other causes having overridden the testimony.”

Steele pointed out to Gov. Coke that the Kelly brothers were related to the Taylors, and that the wife of one of the Kellys was the daughter of Pitkin Taylor, “who was assassinated soon after, as is believed because he took an active part, by employing counsel to prosecute in the trial against Sutton & others.”

The name of John Jackson Helm would not be remembered as the effective leader establishing respect for law and order in a violence-ridden Texas, but as a tyrant creating terror among the people he was sworn to protect.

As Helm ran into the blacksmith shop on that fateful day, intending somehow to escape from the pair intent on killing him, did he not realize that he was now being killed in attempting to escape? Had the chickens finally come home to roost?

This is an edited excerpt of Captain Jack Helm: A Victim of Texas Reconstruction Violence by Chuck Parsons, published by University of North Texas and due out in March 2018.