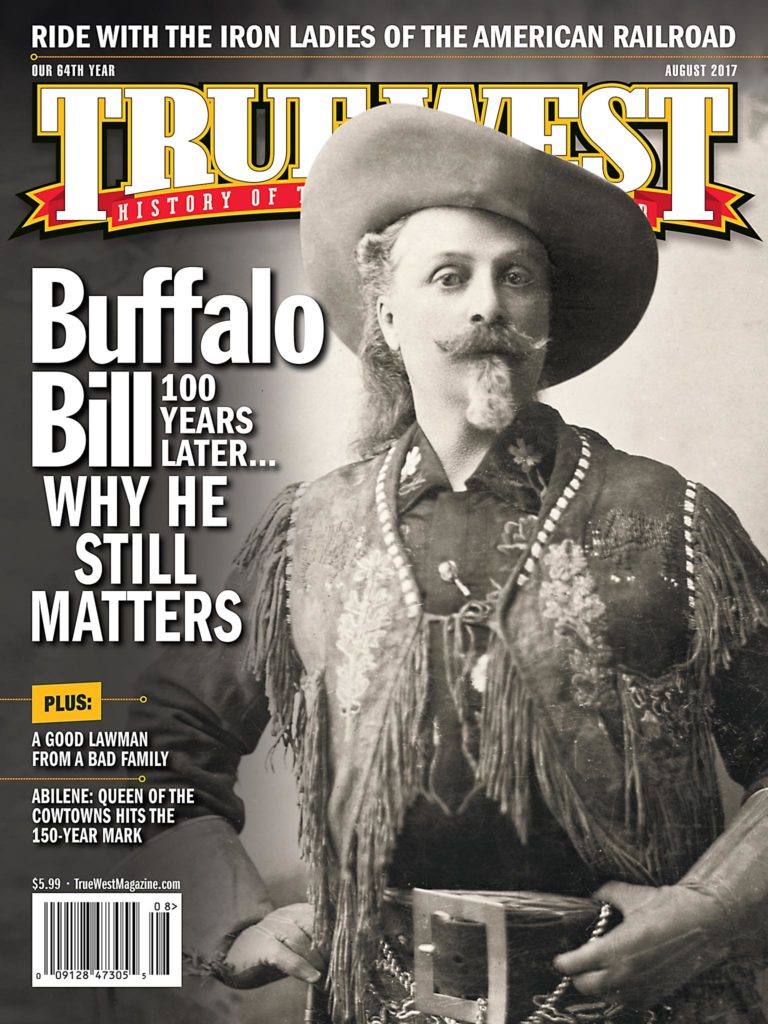

– True West Archives –

William F. Cody was a man seemingly trapped in the distant past, yet one who cared desperately about the onrushing future—for himself, his family, his business and his country.

He was progressive in politics (he favored votes for women long before President Woodrow Wilson came around) and was, for his time and place, enlightened on questions of race and equality.

He had risen from poverty to incredible wealth, was fawned over by kings and queens, presidents and captains of industry, and in his time was the living symbol of “The American.”

The 26th U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt described Cody as an “American of Americans,” adding, “…his memory should be dear to all Americans, for he embodied those traits of courage, strength and self-reliant hardihood which are vital to the well-being of our nation.”

He was, like the nation he came to symbolize, a bundle of contradictions: a hunter who became a conservationist; a friend to American Indians who was famed as an Indian fighter; a rugged frontier scout best remembered as a sequined showman; a living artifact of a pioneer past playing out his role in a world of telephones, motion pictures, automobiles, airplanes, skyscrapers and world wars.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

Cody’s life—from 1846-1917—spanned a period of astonishing change, and he participated in much of it. After his father became a martyr in the fight to keep Kansas free of slavery, the boy fought as a teenager in the Civil War. He rode for the Pony Express; hunted buffalo for the railroad (and earned his nickname, “Buffalo Bill”); scouted for the U.S. Army (Gen. Philip Sheridan appointed him chief of scouts for the 5th Cavalry); earned the Medal of Honor in a fight with the Sioux; took the so-called “first scalp for Custer” in a celebrated duel at Warbonnet (Hat) Creek in 1876; and numbered among his frontier friends “Wild Bill” Hickok, “California Joe” Milner, “Texas Jack” Omohundro, Frank North, Ned Buntline, Jack Stilwell, Spotted Tail, Sitting Bull and Generals Sheridan, Eugene Carr, Wesley Merritt and Nelson Miles.

Cody lived the Wild West from 1846 to 1876, and then he took it on the road—first in stage shows and then in the greatest arena extravaganza of the 19th century (if not of all time) with “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, Congress of Rough Riders of the World” (he never called it a show). It was a romantic adventure, a gilded historical pageant, a combination rodeo and circus, and, most important, a tale of progress.

Cody told Americans, and then people around the world, the story of the birth of the United States. He became the embodiment of the American spirit and presented to the world an image of the rugged American as important to the 19th century as Benjamin Franklin had been to the previous century.

Cody inherited the frontier crown of Daniel Boone, David Crockett and Kit Carson. And with an assist from James Fenimore Cooper, Owen Wister, Frederic Remington, Frederick Jackson Turner and Theodore Roosevelt, he made the story of the American frontier into the nation’s creation myth. Buffalo Bill astride his snow-white stallion presented an image that all the people of a rapidly changing nation could embrace no matter their place of origin.

When Cody died on January 10, 1917, his country—about to march into a future of steam, steel, world wars and international power—paused and reflected on just how far the nation had come in so short a time. Cody, the quintessential American, had all been encompassed in the life of one man. With the passing of Buffalo Bill, the first epoch of America’s story had come to a close.

Paul Andrew Hutton has published 10 books and teaches history at the University of New Mexico. For more on “Buffalo Bill” Cody, he recommends Buffalo Bill on the Silver Screen by Sandra K. Sagala, Buffalo Bill’s America by Louis S. Warren and The Lives and Legends of Buffalo Bill by Don Russell.