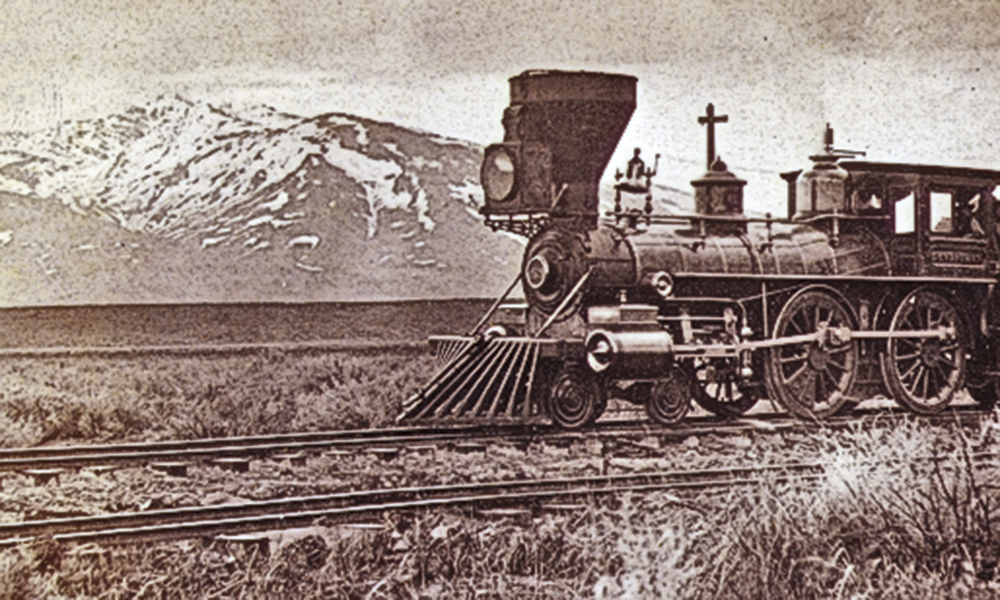

The iron horse evokes images of smoke and cinders billowing from a steam locomotive stack as it sails down the trackless wastes of the frontier. Much like the lore of Old West cattle drives, the legendary construction of the Western railroads inspired a litany of songs and many special colorful terms and bits of doggerel.

An Irish and American folk tune Poor Paddy Works on the Railway immortalized the backbreaking labor of the gandy dancers.

In eighteen hundred and sixty-three,

I came across the stormy sea.

My dung’ree breeches I put on

Chorus: To work upon the railway, the railway,

To work up-on the railway.

Oh, poor Paddy come work on the railway.

Robert Louis Stevenson’s descriptive prose in his 1879 classic The Amateur Emigrant was no less picturesque. He painted a word picture of: “An American railroad car, that long, narrow wooden box like a flat roofed Noah’s ark, with a stove and a convenience, one at either end, a passage down the middle, and transverse benches upon either hand.”

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

Besides the cars, the engine consisted of many parts such as the prow where cowcatcher or pilot which pushed obstructions out of the way. Attached at the opposite end, a tender car carried water or fuel to fire the boiler.

But it was the rails laid by hefty gangs of men, known as navvies, gandy dancers and traqueros dropped the heavy ribbons of iron in place followed by gaugers, spikers and bolters who would make tracks that underpinned the operation.

And where did these trains halt? In the early days, end of track existed at hell on wheels, raucous temporary towns, like Diablo Canyon, Arizona, Deeth, Nevada, and some of which became permanent, like Cheyenne, Wyoming. All Aboard!