– Courtesy Essanay –

“The best movie about Jesse James is Ride with the Devil, which isn’t about Jesse James, but that’s all right because the best movie about George Custer is Fort Apache, which isn’t about Custer, either, and the best movie about the O.K. Corral is My Darling Clementine, which gets almost all of the facts—including the year of the famous gunfight —wrong.”

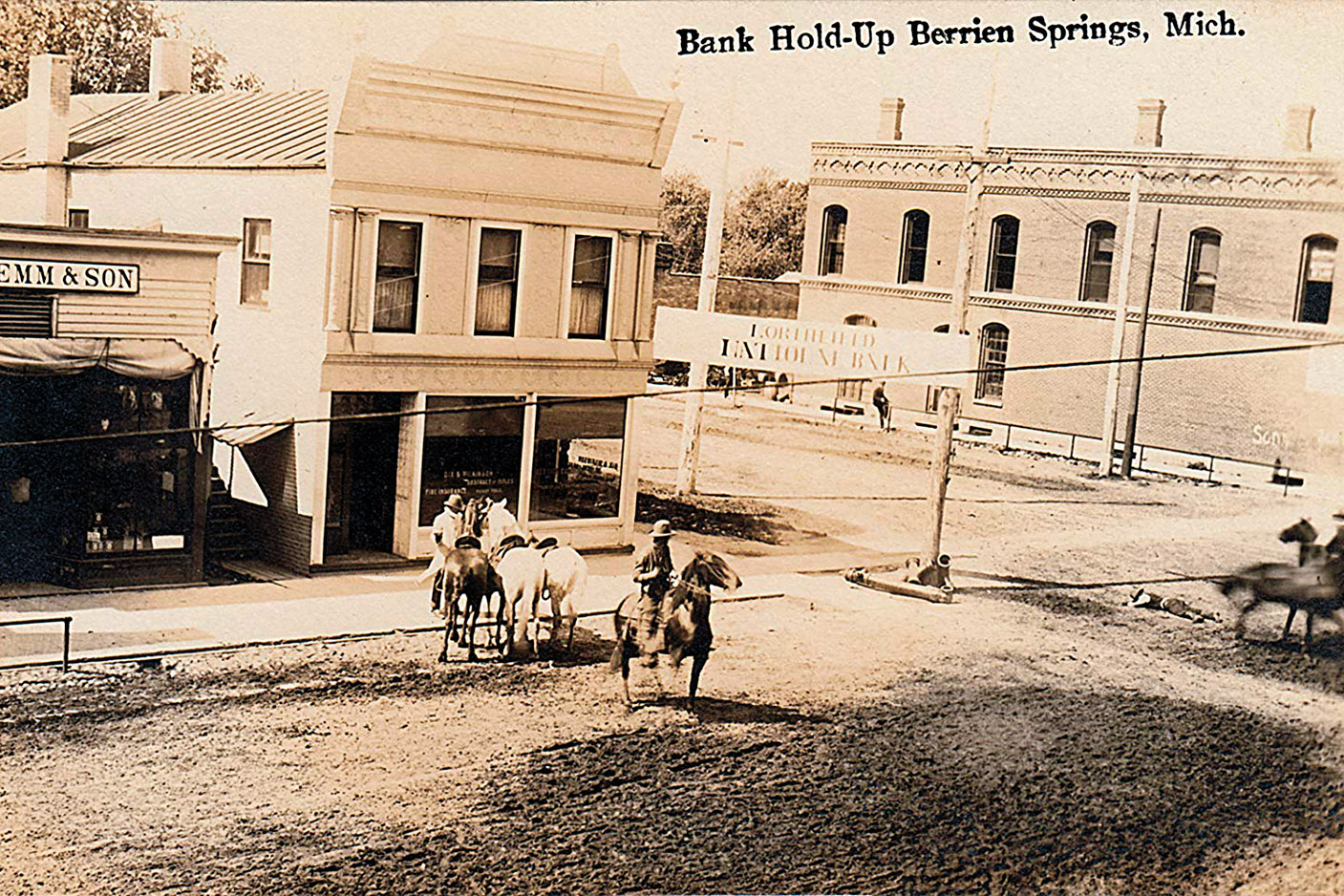

That was the start of a speech I gave in suburban Des Moines, Iowa, in 2006. Hearing that I was writing a novel about the James-Younger Gang’s ill-fated bank robbery in Northfield, Minnesota, John J. Koblas, then president of the National James-Younger Gang, invited me to give the keynote address at the group’s annual conference. Now, the last thing I want to do when talking to historians and, as in the case of the National James-Younger Gang, descendants of historical figures, is bring up a subject sure to prompt arduous debate. After all, I am, primarily, a novelist, albeit one firmly grounded in history. As I explained to Jack Koblas, I did not want to get into a discussion about who was inside the bank in Liberty, Missouri, on February 13, 1866; how many bandits actually took part in the Northfield raid on September 7, 1876; what brand of revolver Robert Ford used when he shot Jesse James to death at his home in St. Joseph, Missouri, on April 3, 1882; the color of Cole Younger’s vest, if he preferred pewter or brass buttons; what cobbler made Jim Cummins’s boots; or whether the Pinkertons were nothing more than hired assassins.

So I told Koblas that I would prefer to talk about something light, maybe the movies featuring Jesse James.

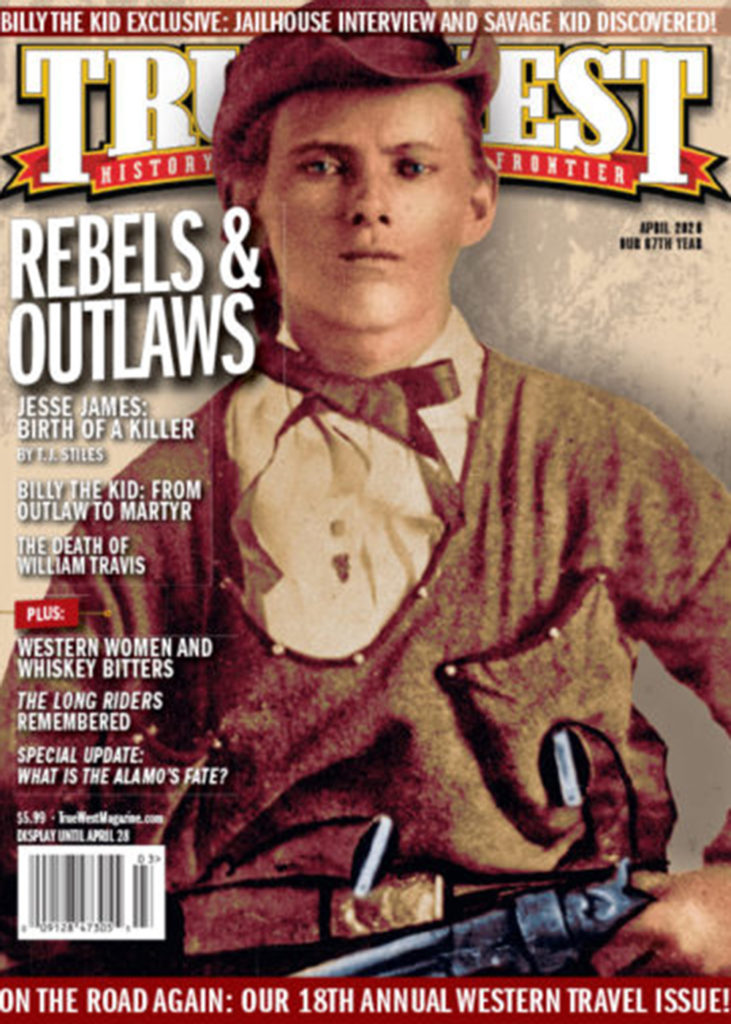

Which isn’t to say film is immune from controversy. Far from it. My speech led to an article on the same subject for True West magazine, which led to a polite though fairly spirited discussion with director Walter Hill during the Western Heritage Wrangler Award festivities at the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, in April 2007. (Hill had directed The Long Riders, a 1980 movie I pretty much dismissed in the True West article.)

The first movie about Jesse James that I recall seeing is Philip Kaufman’s The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid (1972), when it aired on network television in the 1970s. The elementary school playground the following week (or weeks) was full of young boys pretending to be Cole Younger, or at least actor Cliff Robertson’s version of Cole Younger. As naive, white South Carolinians instilled from birth with a glorious admiration for the War Between the States/War for Southern Independence/War of Northern Aggression/Lost Cause, we loved the movie’s line about 1876 not marking our nation’s centennial—Yankees had forgotten four years of Civil War—and a lot of us thought that the James and Younger boys were merely carrying on the fight against Yankee tyranny and greedy railroaders.

– Courtesy Paramount Pictures –

Jesse James was a savvy hero saving girls from greedy land-robbers, much the same as Billy the Kid kept riding to the rescue on the pages of Charlton and Dell comics. Later, I would grow to learn that the Civil War wasn’t so glorious or all that righteous, and neither was Jesse James, although, ever since watching Clif Robertson on the screen of our Sylvania color television set, I’ve always had a grudging respect for Cole Younger. The historical researcher and film buff in me—I’ll take in a Western at the drop of a hat—kept drawing me to Jesse James.

Other movies about Jesse and “the boys” left memorable impressions on me, including Hill’s The Long Riders, which I saw at a theater in Florence, South Carolina, as a high school senior in 1980. Many more came along on television or video such as Jesse James, The Return of Frank James (for my money, no actor could chew tobacco better than Henry Fonda as Frank James), the insipid American Outlaws and, most recently, The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford. Others, especially the B-movies I dug up once I start- ed researching my speech to the National James-Younger Gang. More than a few came along when I got the itch to write this book. Some are, unfortunately, most likely lost forever, and a few are about as elusive as Jesse was to the Pinkertons.

I will still argue that the best movie about Jesse James isn’t really about Jesse James, but Ride with the Devil, director Ang Lee’s 1999 film based on Daniel Woodrell’s novel Woe to Live On. The film superbly captures the turmoil and people along the Missouri-Kansas border, and the events during the Civil War that propelled the real Jesse James to a life of crime.

– Courtesy Paramount –

If any famous Western historical figure is overdue for film analysis, it is Jesse James.

Eight theatrical movies have been made about the gunfight at the O.K. Corral, most notably the aforementioned My Darling Clementine, Gunfight at the O.K. Corral (1957), the pseudo-cult favorite Tombstone (1993), and a handful more if you include movies inspired by the event, such as Law and Order (1932) and Warlock (1959). According to historian Paul Andrew Hutton, 48 movies have been made about George Armstrong Custer, from Francis Ford’s Custer’s Last Raid (1912) to Arthur Penn’s Little Big Man (1970), with the fabled “Boy General” appearing in several other films including The Plainsman (1936) and Santa Fe Trail (1940), along with cameo and comic appearances in Won Ton Ton, the Dog Who Saved Hollywood (1976), Teachers (1984), Wagons East (1994), etc.

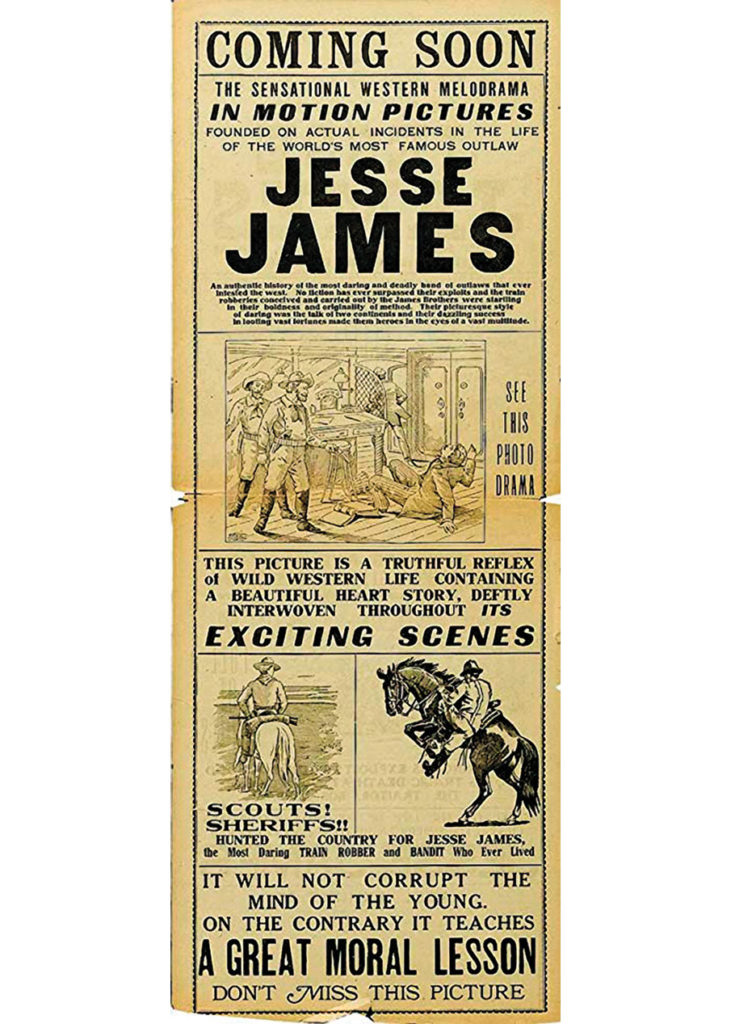

Jesse James has shown up in 40-odd movies, beginning—as far as we know—with The James Boys of Missouri in 1908. “At this point, this corner is willing to concede that Frank and Jesse James are among the most photographed characters of our folklore,” The New York Times reported in 1951. If you take into consideration foreign films, short subjects and brief appearances in television movies such as The Last Ride of the Dalton Gang (1979) and Belle Starr (1980), that number grows substantially.

The truth, however, is that because so many silent movies are presumed lost, we may never know the exact number of movies about Jesse and Frank James.

As a cult icon, Jesse has gone even further, popping up in the Western television series Bronco, Hondo, Stories of the Century, Tales of Wells Fargo, Barbary Coast, Little House on the Prairie and The Young Riders. Yet the popularity of the Missouri bandit hasn’t been restricted to TV shows with horses and hats. In a 1953 episode of the Walter Cronkite-hosted documentary re-enactment series You Are There, an up-and-coming actor named James Dean played Jesse in “The Capture of Jesse James.” Jesse has also gotten his due on The Brady Bunch, MacGyver, The Dukes of Hazzard, even My Favorite Martian and The Twilight Zone.

The only Western outlaw more popular in Hollywood is Billy the Kid. “At least 60 films, both American and foreign, have celebrated the exploits of this dreamscape desperado,” writes Hutton of Billy the Kid. Yet most of the movies about Henry McCarty, alias Henry Antrim, alias William H. Bonney, alias Kid Antrim, alias Kid, alias The Kid, alias Billy the Kid, were a series of some 13 matinee B-movies for Producers Releasing Corporation starring Buster Crabbe (released between 1941 and 1943), and more than 20 other films from 1943 to 1946 in which the name of Crabbe’s hero was changed to Billy Carson. Bob Steele also had a run as Billy the Kid with five movies released by PRC in 1940 and 1941.

Hollywood did produce some serious studies of Billy the Kid, including King Vidor’s Billy the Kid (1930), Arthur Penn’s The Left Handed Gun (1958, featuring Paul Newman as a brooding Billy) and Sam Peckinpah’s muddled Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid (1973).

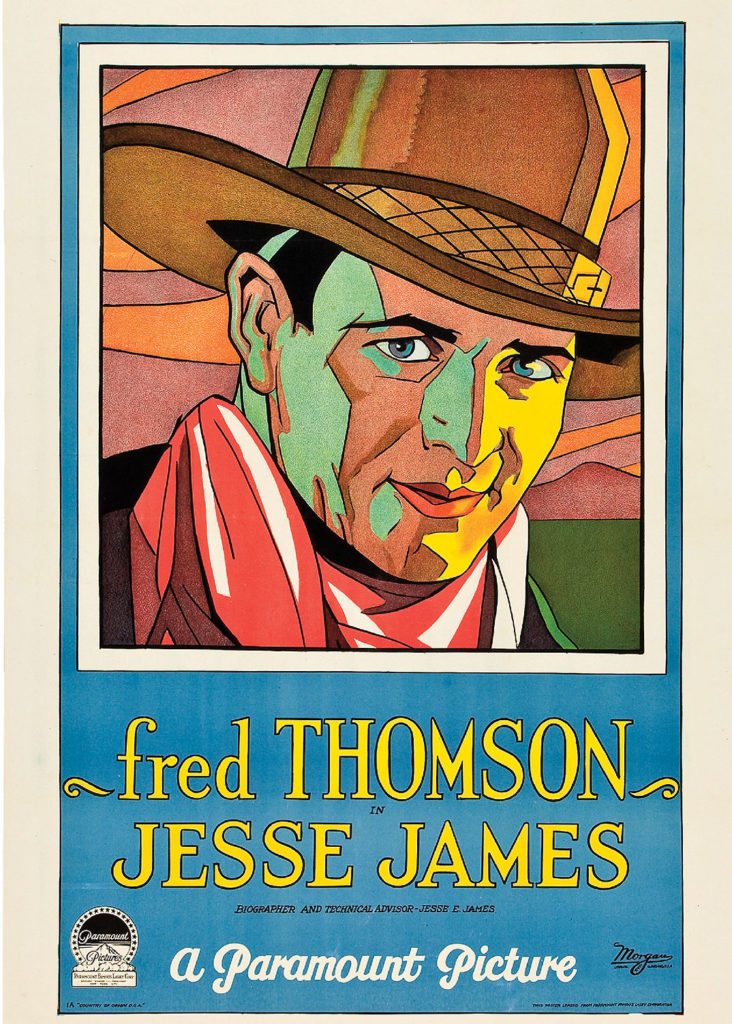

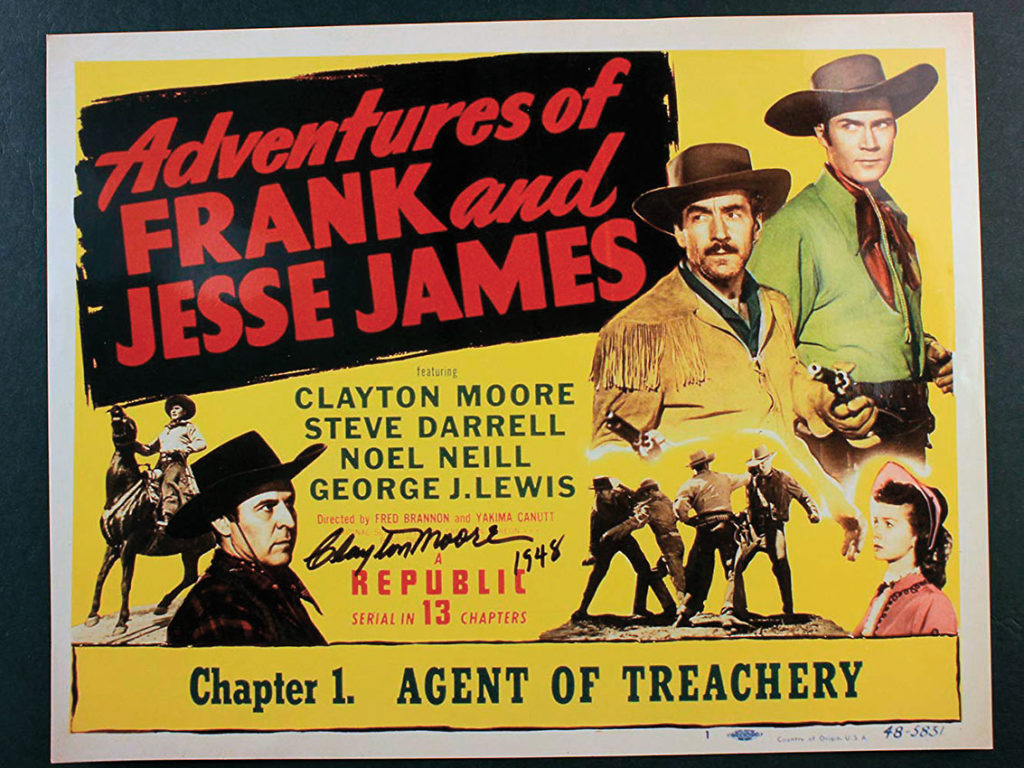

The movies featuring Jesse James also prove to be an interesting mix worthy of discussion, review and analysis. For casting purposes, it is hard to top the fact that Jesse James has been played on screen by his own son, in Jesse James Under the Black Flag (1921) and Jesse James as the Outlaw (1921). Matinee idol Roy Rogers played him as half of a dual role in Jesse James at Bay (1941); Rogers had already played against Don “Red” Barry’s Jesse in Days of Jesse James (1939). Clayton Moore, of The Lone Ranger fame, also got two turns as Jesse in the Republic serials Jesse James Rides Again (1947) and Adventures of Frank and Jesse James (1948), as did Audie Murphy in Kansas Raiders (1950) and A Time for Dying (1969), Murphy’s last role. Jesse has shown up in the comedies Alias Jesse James (1959) with Bob Hope and The Outlaws IS Coming! (1965) with The Three Stooges, and has also had the non-distinction of appearing in one of the worst horror films ever made, Jesse James Meets Frankenstein’s Daughter (1966).

– Courtesy Screen Guild –

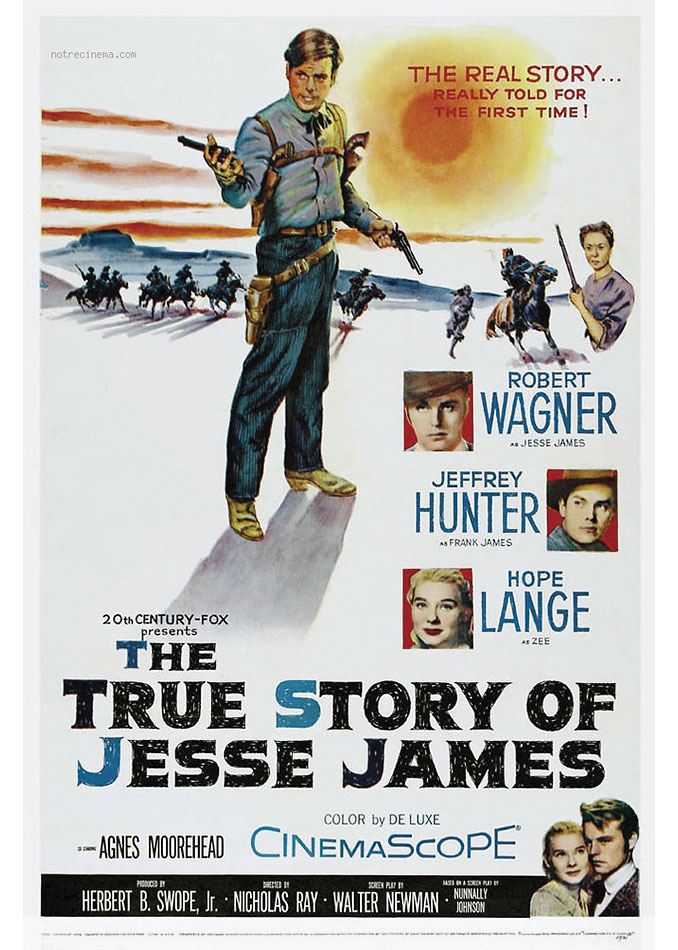

“By my count, there have been 36 movies about Jesse James and not one has attempted to tell the truth, even though the truth is more exciting than the myths,” Judge James R. Ross, Jesse’s great-grandson, wrote for the Los Angeles Times after the release of American Outlaws in 2001. “And the love story of Jesse and his cousin, Zee [Mimms], is more poignant and beautiful than any of the false stories.”

Ross went on: “I’ve spent 50 years opposing the most popular myths associated with my great-grandfather, and I challenge anyone to point out any movie that is more exciting than the real story. I hope that one day someone in the entertainment industry will produce an exciting movie of outlaws and gunslinging, filled with a tremendous love story, and yet remain true to the life of Jesse James.”

History and entertainment can be a precarious balance. I’ve often said that two of the most historically accurate films I have seen are the Civil War epic Gods and Generals (2003) and Son of the Morning Star (1991), the television miniseries about George Custer. As far as entertainment value, alas, those pictures are about as enthralling as watching coffee boil.

– Courtesy 20th-Century Fox –

Movies aren’t made to be historically accurate, but to entertain.

John Wayne is said to have once remarked that shorter stories make better movies, which might explain why Hollywood can produce entertaining films about a 27-second street fight in Tombstone, Arizona, but stumble over the life and times of Jesse James, whose career as an outlaw lasted sixteen years—and even longer if you include his years as a Confederate guerrilla during the Civil War. Such a life is hard to boil down into two hours.

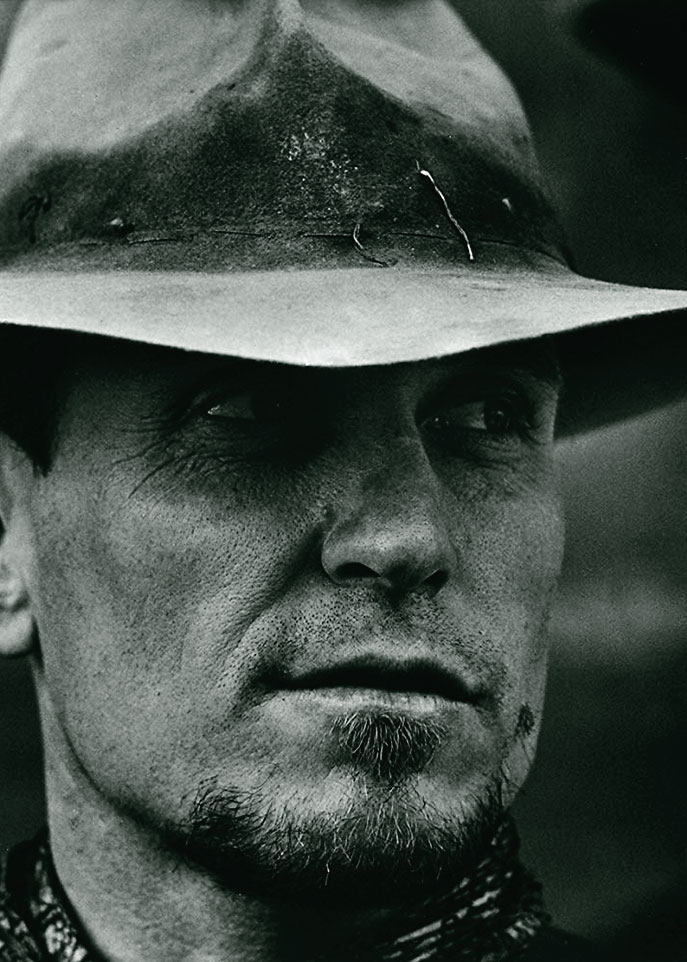

As far as Jesse is concerned, most movies fail to capture the essence of the man, or the times in which he lived, although The Last Days of Frank and Jesse James, a 1986 made-for-television movie, and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007) come close. The Long Riders (1980) and The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid (1972) deserve points for trying to capture an authentic look. I also find much to admire in I Shot Jesse James (1949), Sam Fuller’s first movie as director.

Besides, I also believe that some of those B-movies, with no basis on or knowledge of history, can be entertaining if you take them for what they are. You can even find a kernel of truth in them, as Frank James (played by Don “Red” Barry) tells a former gang member in Gunfire (1950): “The outlawing died when Jesse died, Matt.”

– Courtesy Universal –

Perhaps the ending of Jesse James (1939), arguably the most famous and most popular movie about the outlaw, provides a clue as to the world’s fascination with Jesse James. Actor Henry Hull, playing Major Rufus Cobb (a character inspired by John Newman Edwards, the Missouri journalist who championed the real Jesse James), delivers his sermon and eulogy:

“There ain’t no question about it. Jesse was an outlaw, a bandit, a criminal. Even those that loved him ain’t got no answer to that. But we ain’t ashamed of him. I don’t know why but I don’t think even America is ashamed of Jesse James. All I do know is he was one of the dog-gonest, goldingus, dad-blamedest buckaroos that ever rode across these United States of America.”

Like Billy the Kid, Jesse James is equally a “Dreamscape Desperado.” He has ridden the range as hero, villain and impostor in A-list movies and B’s, serious studies and simple schlock, and undoubtedly will ride again.

And who knows myth better than Hollywood?

– Courtesy Warner Brothers –