– Courtesy Beinecke Library, Yale University –

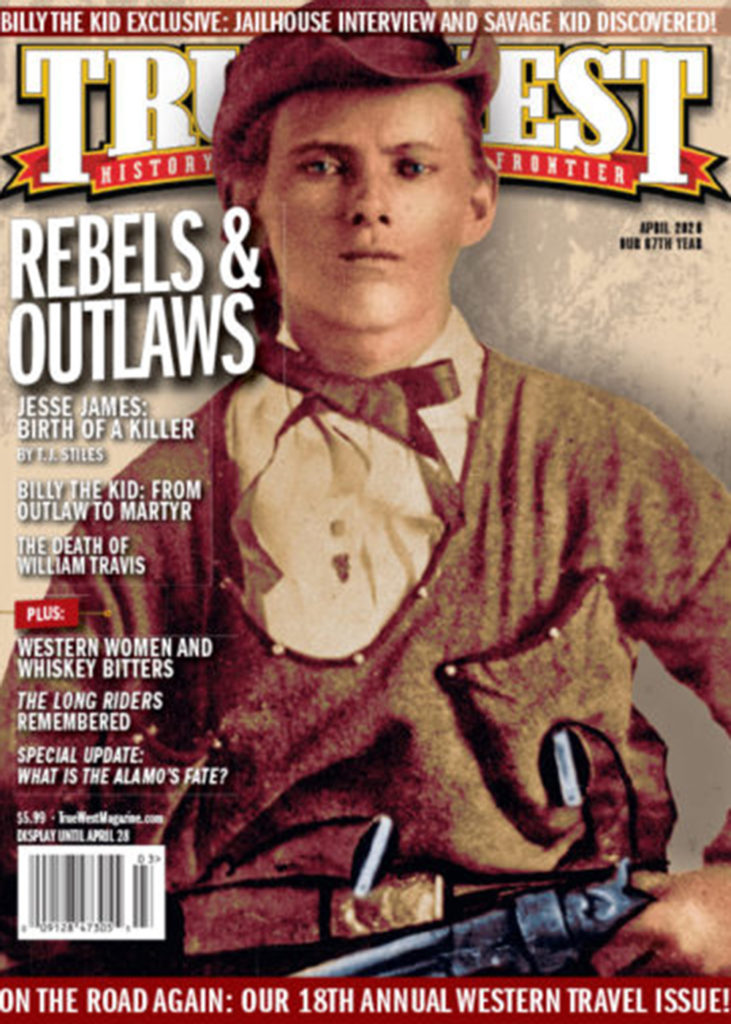

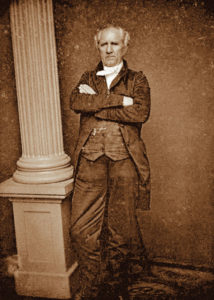

Twenty-seven-year-old William Barret Travis carried considerable weight on his shoulders in the wee morning hours of March 6, 1836. The native South Carolinian had emigrated from Alabama to the Mexican state of Coahuila y Téjas five years earlier for a new beginning. Now in the Alamo, a former Franciscan mission serving as a fort, he may have contemplated his impending end rather than a beginning.

Travis held the rank of lieutenant colonel in Texas’s newly formed cavalry, yet he commanded a fortification, a job more suited to an artillery officer. He had shared leadership with Col. James Bowie at the beginning of the siege, but illness rendered the frontiersman bedridden early on, leaving Travis in full command.

Travis penned his famous letter of February 24, 1836, the same day as Bowie’s incapacitation, addressed to “The people of Texas and all Americans in the world.” He stated his intention “…to sustain myself as long as possible & die like a soldier who never forgets what is due to his own honor & that of his country,” if Texas neglected his calls for assistance. He had sustained himself and his garrison for 12 days. Now the time had come to fulfill his pledge to honor and country.

– Courtesy Sally Mauck, Liz Case Pickens and Bob Sanders –

Alamo historians and aficionados have debated the finer details of the battle for decades. Two of the more spirited subjects involve the exact manner in which the American icons Bowie and Davy Crockett met their ends, approximately nine and 25 versions respectively. Less attention has been paid to the exact mechanism, time and place of Travis’s demise. However, speculation and questions surrounding his death began within a week of the battle.

Word of the Alamo’s fall reached Sam Houston in the town of Gonzales, 70 miles east of San Antonio, on March 11, 1836, by Tejanos Anselmo Vargara and Andres Bárcinas. They had not witnessed the battle themselves but reported information from an Antonio Perez. There is no evidence that Perez witnessed the fight since he rode from the ranch of José Maria Arocha to San Antonio on March 6, the morning of the battle. Whatever information Vargara and Bárcinas shared caused their detention by Houston, possibly for fear of them being spies of Santa Anna but more likely to stave off panic among the assembling Texans.Their information sparked stories of Travis dying as a suicide. E.N. Gray stated in his March 11 letter, “Travis killed himself.” Andrew Briscoe writing to the Red River Herald provided a reason for Travis’s suicide: “The brave and gallant Travis in order to save himself from falling into the hands of the enemy shot himself.” Details shifted during the next few days. Houston reported that Travis, “…rather than fall into the hands of the enemy, stabbed himself.” Benjamin Briggs Goodrich, whose brother John died at the Alamo, wrote on March 15, “Col. Travis, the commander of the fortress, sooner than fall into the hands of the enemy, stabbed himself to the heart and instantly died.”

The story evolved, however. Five days later in Nacogdoches, Texas, John T. Mason wrote to a Major Nelson commanding Fort Jesup in the United States, “Travis and all his men [were] captured and murdered.” E. Bowker, writing from St. Augustine, Texas a week later, assured a relation, “Col. Travis the Commander of that little Band [sic] was found dead grappled with a Mexican Officer with his sword through his body,” leaving unsaid whose sword went through whose body.

The man able to clear up the mystery, Travis’s slave Joe, who arrived in Gonzales two days after Vargara and Bárcinas, had another story to tell. He came to the Texan forces with Susanna Dickinson and her young daughter, all three survivors from the Alamo. He later described the battle to Texan officials at Washington-on-the-Brazos. Several witnesses recorded his account, embellished it and passed it on to a number of newspapers in the United States.

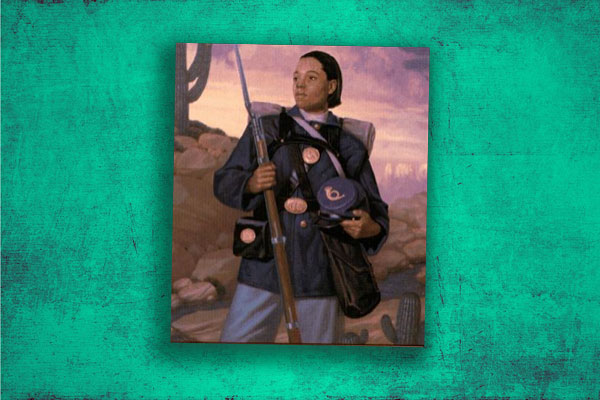

– Courtesy The Alamo, Texas Historical Commission, photo of painting by William Groneman –

George C. Childress, former editor of The Nashville Banner reported that Travis had been awakened in the early morning hours of March 6 by a cry from the guard on the wall “Col. [sic] Travis the Mexicans are coming!” Travis sprang from his blanket, grabbed his double-barreled gun and sword and with Joe mounted one of the ramparts. The fast-moving enemy already had placed scaling ladders against the wall. Travis fired his gun on them and immediately suffered a gunshot wound in return. He fell within the fort while his gun fell among the Mexican soldiers.

Childress further stated that a Mexican general leading his troops over the wall attempted to behead Travis but the wounded colonel raised his sword and killed the general. Joe retreated to one of the rooms of the Alamo and thus survived the slaughter.

The presentation of this account makes it seem as if Joe witnessed the final death struggle between Travis and the general, however later on it states that an English-speaking Mexican officer, and Santa Anna himself, made Joe point out Travis’s body. Only through their conversation did Joe come to believe that Travis killed a Mexican officer and this only because their bodies were close enough that their “blood then congealed together.” No actual witness is cited to confirm this last defiant act by Travis.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

Other participants or claimed participants of the battle left statements regarding Travis’s death over the years compounding the mystery. The earliest appeared in a newspaper, El Mosquito Mexicano, on April 5, 1836, as part of an account by an unidentified Mexican soldier. It merely stated: “The chief they called Travis died like a brave man with his gun in his hand, in back of a cannon.” He did not say that he actually witnessed his death.

Twenty-four years later, Francisco Ruiz, who claimed to be the Alcalde of San Antonio in 1836, stated for the Texas Almanac of 1860 that he had been called upon to identify Travis’s body for the Mexicans. He said, “On the north battery of the fortress lay [sic] the lifeless body of Col. Travis on the gun-carriage, shot only [sic] in the forehead.

Filmmakers and artists have loved this touch, giving their Travis character or image a neat little red spot on his forehead indicating a bullet wound. Some historians while constructing a dramatic telling of the Alamo story have melded Ruiz’s words with those of Joe, giving the impression that Joe witnessed Travis being felled by a single shot to the forehead. Had Travis been smacked in the forehead with a Mexican army musket ball approaching .69 caliber, it is very unlikely that he would have been in any condition for a later death struggle with a Mexican officer.

– True West Archives –

Many Alamo historians accept Ruiz’s story at face value without further investigation. The late Thomas Ricks Lindley in his book, Alamo Traces (2003), presents evidence showing that Ruiz may not have been in San Antonio during the battle.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

Susanna Dickinson in 1875 stated that “Cols. Travis and [James Butler] Bonham were killed while operating the cannon, the body of the former lay on top of the church.” That same year, Francisco Becerra, believed to have been a Mexican sergeant in the battle, related a story in which Mexican soldiers found Travis and Davy Crockett indoors. Travis seized a gun’s bayonet pointed at him and depressed the muzzle to the floor. Other soldiers opened fire and a bullet struck Travis in the back. “He then stood erect, folding his arms, and looked calmly, unflinchingly, upon his assailants. He was finally killed by a ball passing through his neck.” Becerra went on to say that Crockett stood in a similar position and they died, “undaunted like heroes.”

– True West Archives –

An 1889 article in The Fort Worth Gazette cited Felix Nuñez, who claimed Travis manned a cannon just outside the open door of the Alamo church. Mexican cannon and small arms fire silenced the Texan gun and killed Travis.

Ten years later newspapers cited the celebrated Madam Candelaria after her death on February 10, 1899, stating, “Colonel Travis was the first man killed. He fell on the southeast side near where the Menger hotel stands.” Alamo historians today argue Candelaria’s presence in the fort during the battle. Her ever-changing tales of the Alamo include three versions of Bowie’s death and two wildly variant death scenes for Crockett.

Travis lacked the star power and legendary image of a Jim Bowie or Davy Crockett. His last moments never excited the same controversy or curiosity as those of the other two Alamo heroes. However, the conflicting accounts by eyewitnesses, or claimed eyewitnesses, still provide enough mystery to spark conversation as to how and where he died.

Joe, the only survivor with Travis during the battle, provides the best bet on his transition into eternity. He fired his double-barreled gun and immediately fell to enemy fire, one of the earliest Texan casualties of the battle.

– True West Archives –

Travis held the Alamo garrison together during two grueling weeks of siege. He did not lead from the rear during the final fray but mounted the walls to face his enemy. Never forgetting “…his own honor or that of his country,” he fulfilled his promise to the people of Texas and all Americans in the world, and died like a soldier.

Travis’s Pleas For Help

Travis’s second letter from the Alamo, written on February 24, 1836, is famous for its closing salutation, VICTORY OR DEATH.

– Transcription Courtesy William Groneman –

Commandancy of the Alamo

Bejar, Feby. 24, 1836

To the People of Texas & All Americans in the World

Fellow citizens & compatriots

I am besieged, by a thousand or more of the Mexicans under Santa Anna I have sustained a continual Bombardment & cannonade for 24 hours & have not lost a man The enemy has demanded a surrender at discretion, otherwise, the garrison are to be put to the sword, if the fort is taken I have answered the demand with a cannon shot, & our flag still waves proudly from the walls I shall never surrender or retreat. Then, I call on you in the name of Liberty, of patriotism & everything dear to the American character, to come to our aid, with all dispatch The enemy is receiving reinforcements daily & will no doubt increase to three or four thousand in four or five days. If this call is neglected, I am determined to sustain myself as long as possible & die like a soldier who never forgets what is due to his own honor & that of his country VICTORY OR DEATH.

William Barret Travis,

Lt. Col. comdt.

P.S. The Lord is on our side. When the enemy appeared in sight we had not three bushels of corn. We have since found in deserted houses 80 or 90 bushels and got into the walls 20 or 30 head of Beeves. Travis

The day before Travis’s famous letter “To the People of Texas & All Americans in the World,” he sent an initial call for aid from the Alamo on February 23, 1836.

Commandancy of Bexar

Feby. 23rd, 3 o’clock P.M., 1836

To Andrew Ponton, Judge and Citizens of Gonzales, February 23, 1836

The enemy in large force are in sight. We want men and provisions. Send them to us. We have 150 men and are determined to defend the Alamo to the last. Give us assistance.