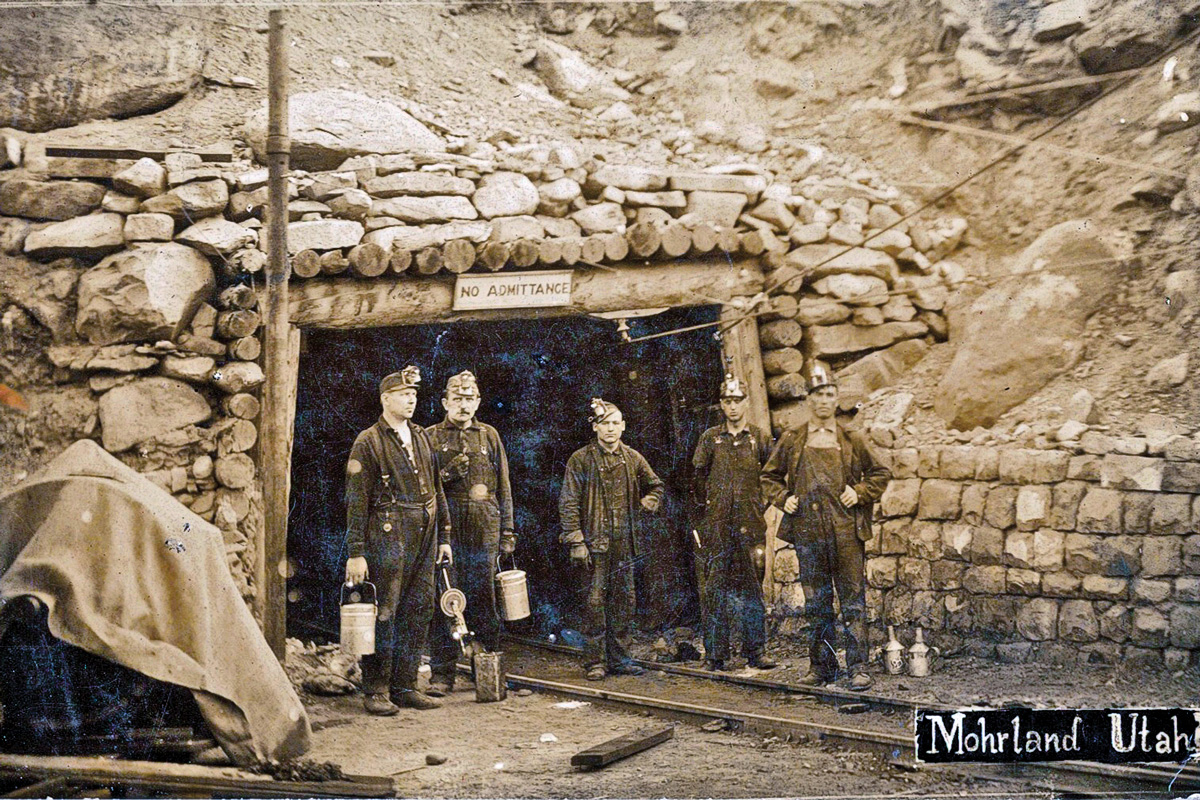

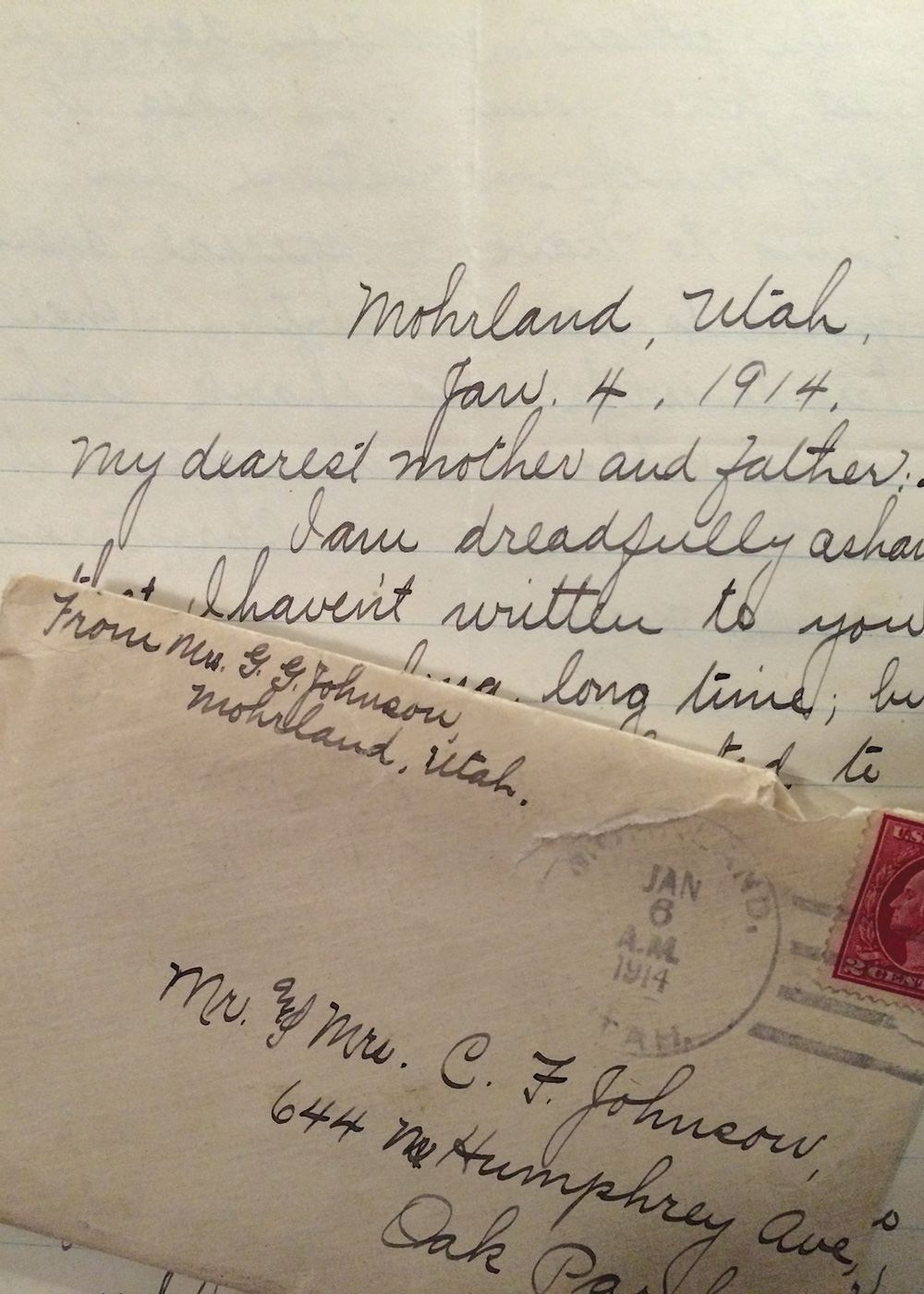

Olive Johnson stood on the train station platform in Price, Utah, on an early September morning in 1913. She waited to hear the locomotive’s whistle signal its readiness to transport her deeper into the West, to begin her next chapter as a schoolteacher in a coal mining camp.

Yet, the train never arrived. She asked the operator what time it would leave for the town of Mohrland.

“Don’t think there will be a train today,” he said.

Somewhat exasperated, Olive waited, daring not to stray far from the depot, as the train ran only when there was enough coal.

“Lordy! This is life in the West,” she wrote her husband, Gus. They had married in her Colorado home after meeting at her family’s ranch. He was finishing construction at Salt Lake City’s new Capitol building before joining her.

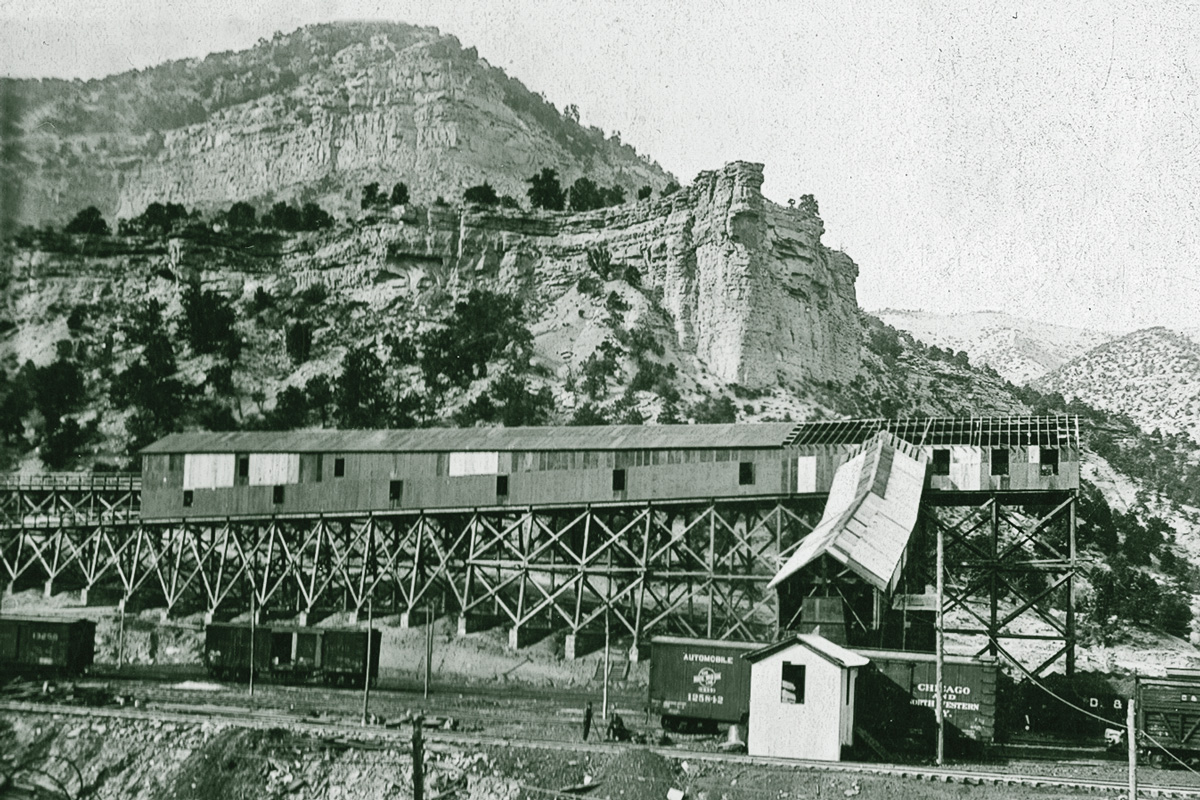

Olive was pleasantly surprised, though, upon finally reaching Mohrland nestled in the mesas and valleys of the mineral-rich rocks. “No farming for ten miles around,” she wrote, and in nearby Black Hawk they were “building about four saloons where there were six fellows to every woman.”

The principal of the school met Olive at the train station, running to greet her in fear that she wasn’t coming. Olive quickly made home in a cottage for $9 a month, complete with electric lights, water and furnishings, in a life continuously accompanied by a layer of coal dust.

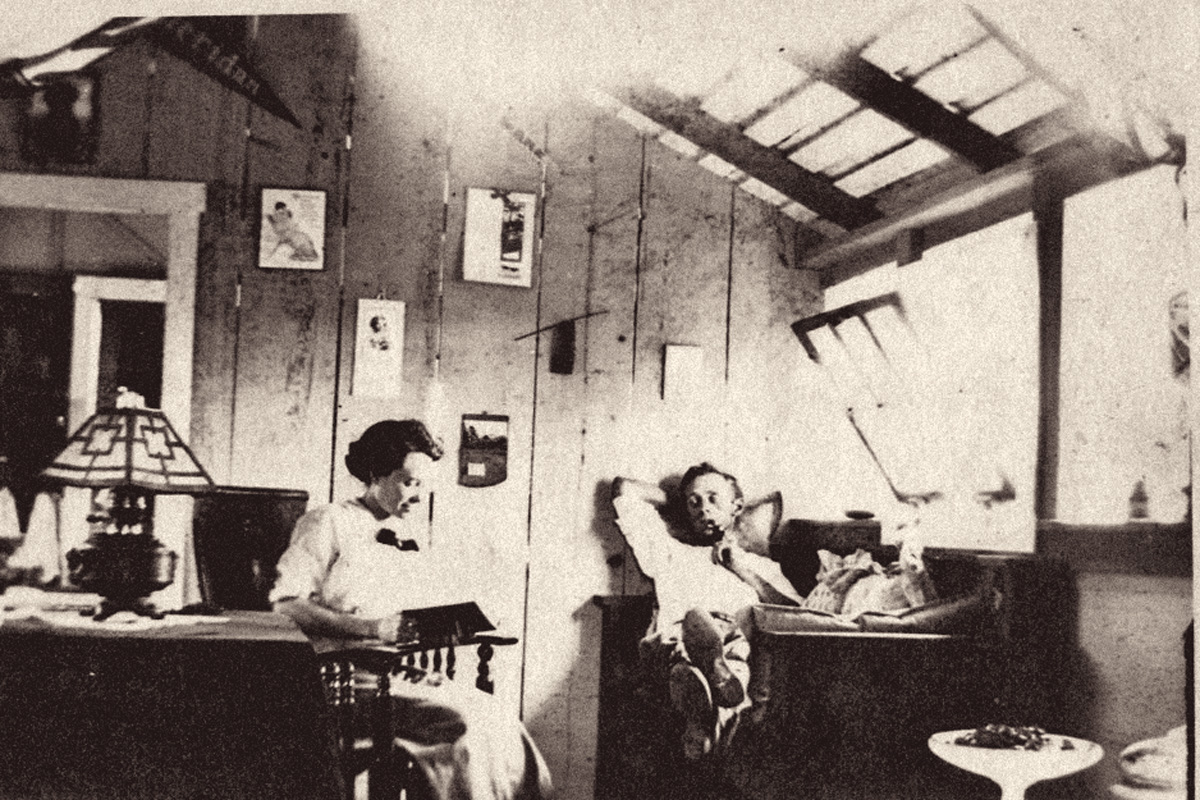

Gus soon joined his wife. He worked in construction to help build the camp’s coal tipple. The couple quickly fell into routine, building a hardworking and cheerful life together.

“We really don’t have time for anything—if we do—we must take it off our sleep—which goes pretty hard in this altitude (nearly 8,000 ft). Our evenings are spent in cooking for the next day and school work. Saturdays in washing and ironing. Gus had to work nearly every Sunday…and we are so happy.

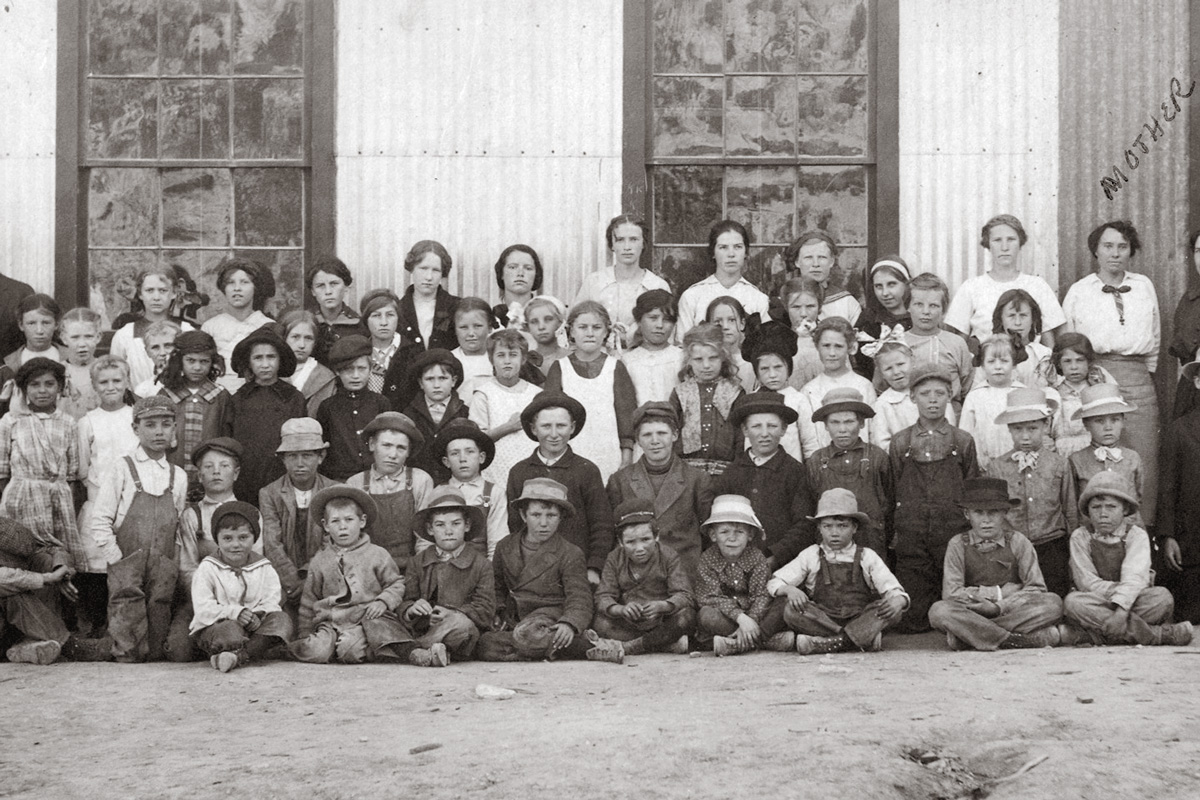

Olive taught 49 primary students in her one-room schoolhouse for $80 a month. Many children were from families who immigrated from Greece, Italy, Japan and Austria to work in the mines, students of both Mormon and non-Mormon faiths. The coal camp was organized according to the international backgrounds—Olive would buy bread from the Greek baker, and the Italian milkman would leave a quart of milk on her porch every morning at 9 am.

A pastime that brought everyone at the camps together was baseball. Workers in the mine received higher wages if they played on the team, and games provided grand social events. Dances also enlivened community spirit, with desks in Olive’s schoolhouse pushed aside to make room for the “Sawmill Savages” orchestra to celebrate the miners breaking the record of 42 trips of coal in one day.

Olive was soon promoted to principal, but she and her husband departed Mohrland a few years later in 1915, to continue on their westward journey to Oregon.

The coal mining camp gathered together to host a farewell to the woman who greeted each morning with positivity, hard work and fortitude—contributing those values to the foundation of their community and a strong thread of the Western fabric.

Dr. Raley read a speech about Olive’s time in the camp:

“She has so endeared herself to every one of us…she has been our teacher, preceptress, friend…we feel now that her place cannot be filled by any other. Signed, the People of Mohrland.”