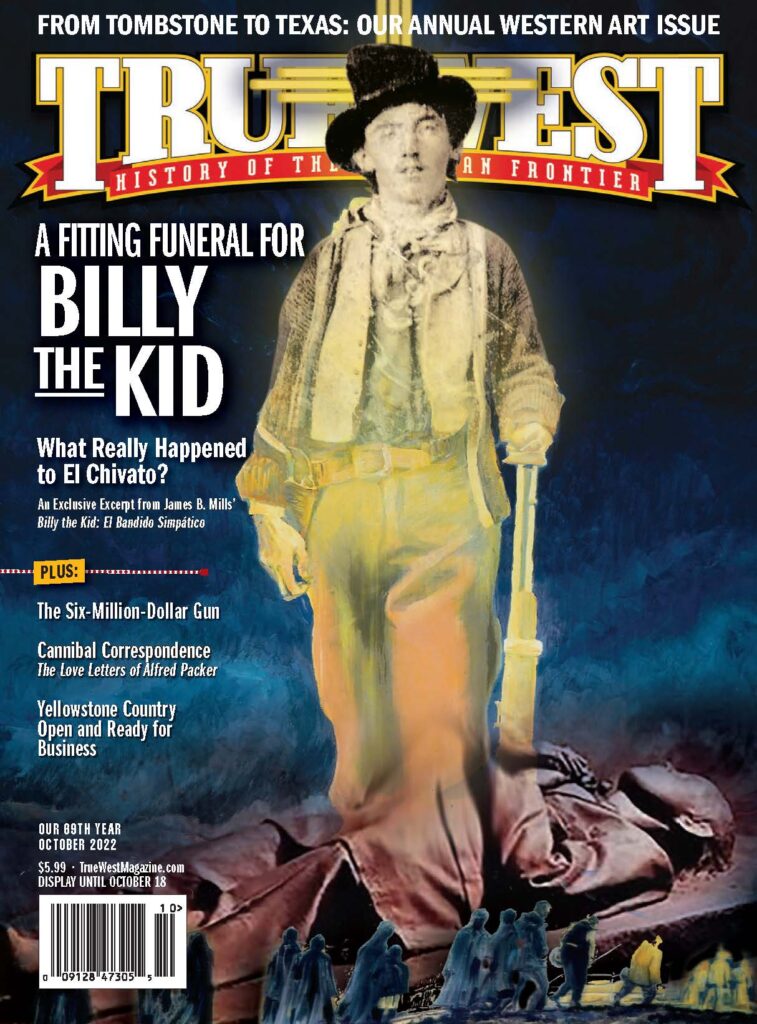

What Really Happened to El Chivato?

Billy arrived at the home of Celsa and Saval Gutiérrez, where he sometimes had a siesta, instead of the Maxwell house. He was carrying a hock of beef leg and headed into the kitchen before returning to the room where Celsa and her husband were situated.

“Celsa, I brought some meat for you to make my supper,” the Kid said.

Although Billy presumed Señora Gutiérrez could manage something with it, upon seeing the hock of a leg in the kitchen, the güero beauty knew it was pointless to even try.

“Beely, this meat that you brought is no more than a bone,” Celsa called out. “It doesn’t have any meat.”

“Give me a knife to go get some good meat,” Billy answered from the other room in Spanish. “And tell Don Pedro that I took the meat so that he doesn’t think that another stole the meat.”

Celsa’s seven-year-old illegitimate son Candido watched as Billy took the butcher knife that his mother loaned him. The Kid headed outside and made his way down inside the white pickett fence parallel with the western end of the parade ground. A full moon shone down upon him; he was in his stocking feet, dark pants and a white dress-shirt with a silk handkerchief around his neck. He briskly walked past the dance hall and flower garden to his left and was fastening his trousers as he approached the Maxwell house. It was almost 12:30 in the morning of Friday July 15, 1881.

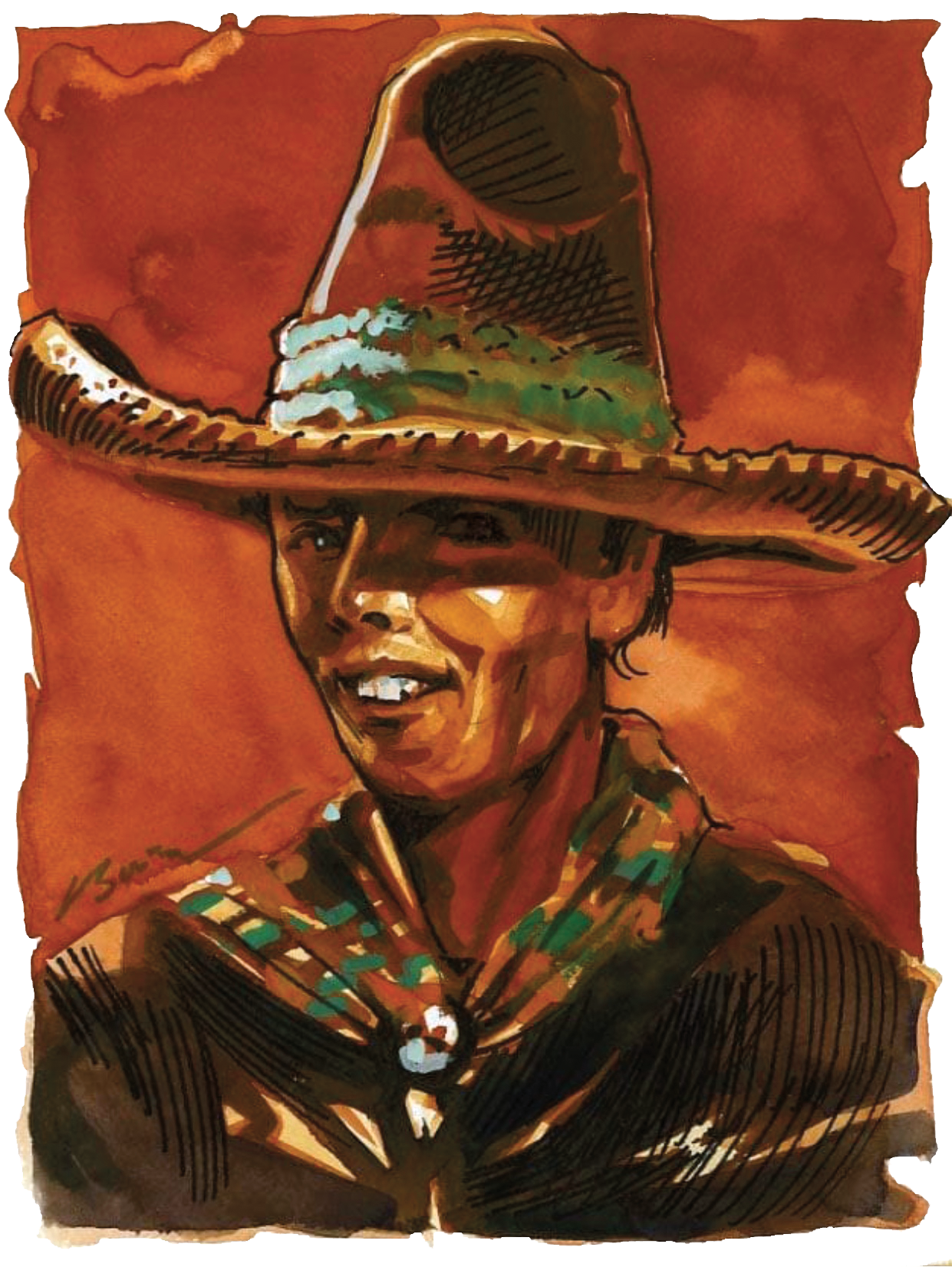

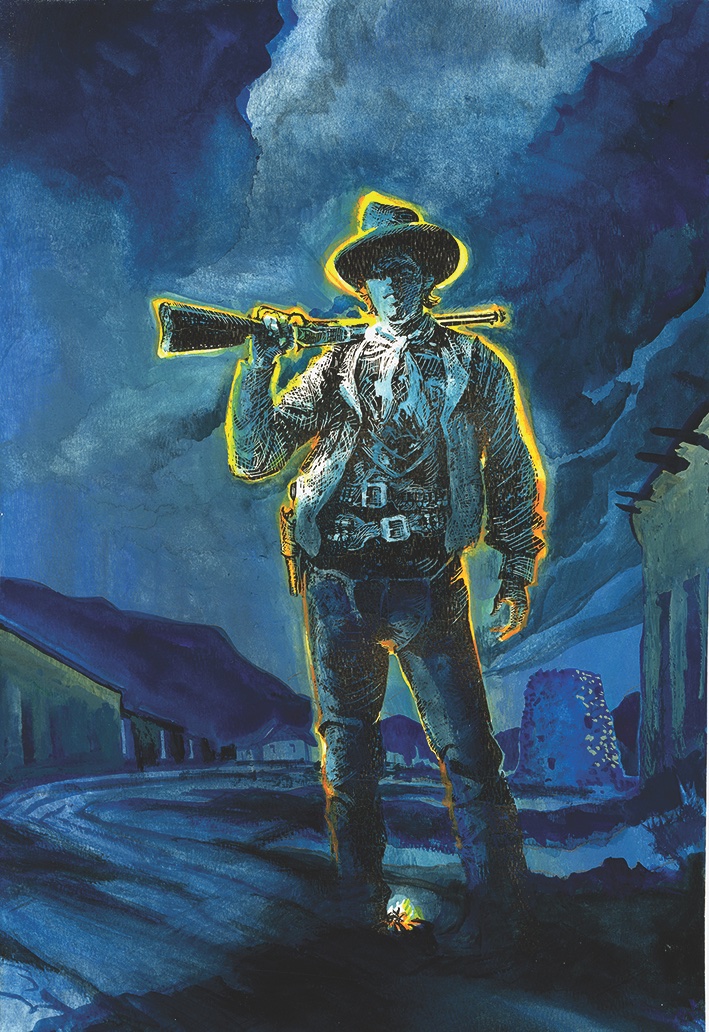

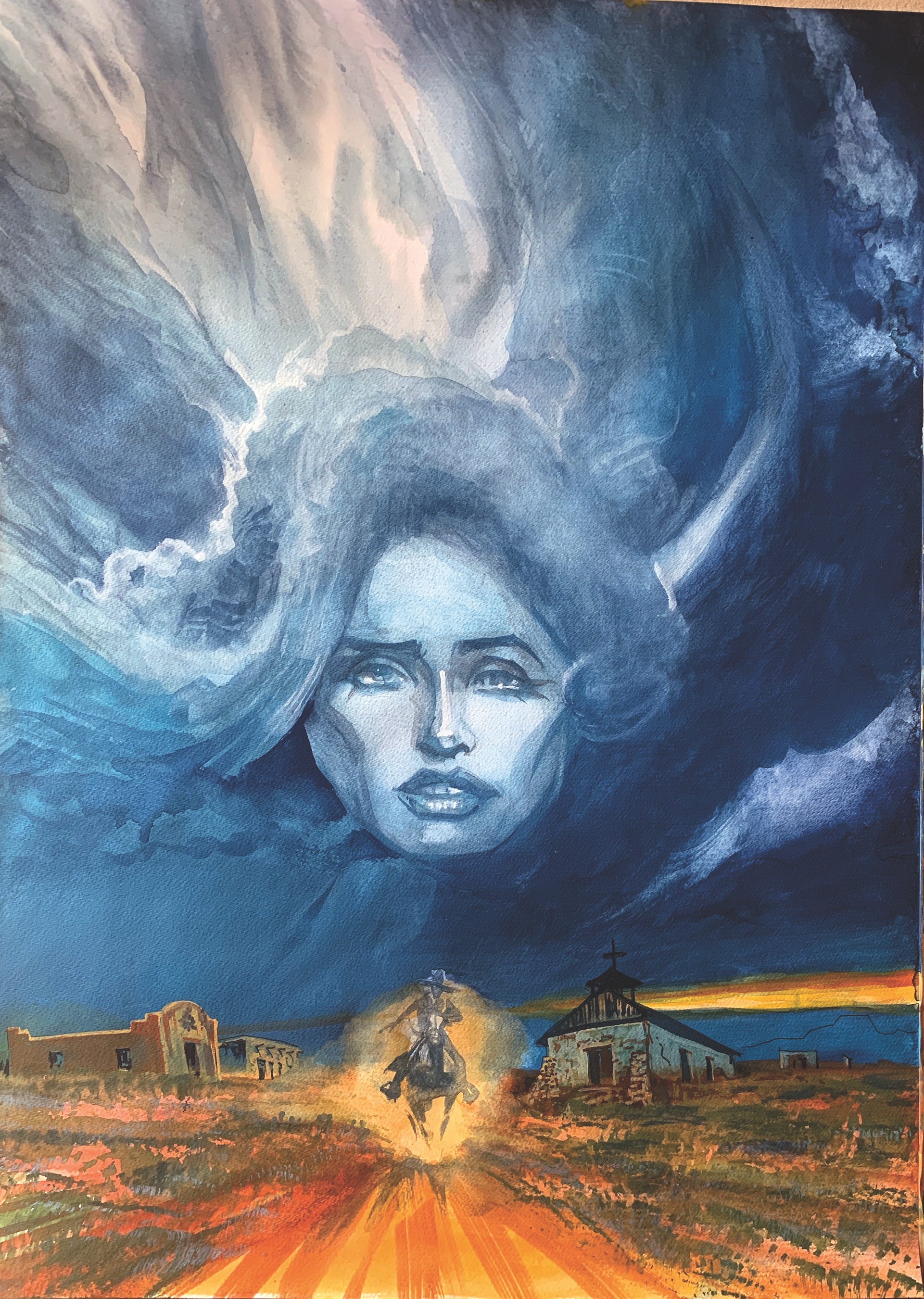

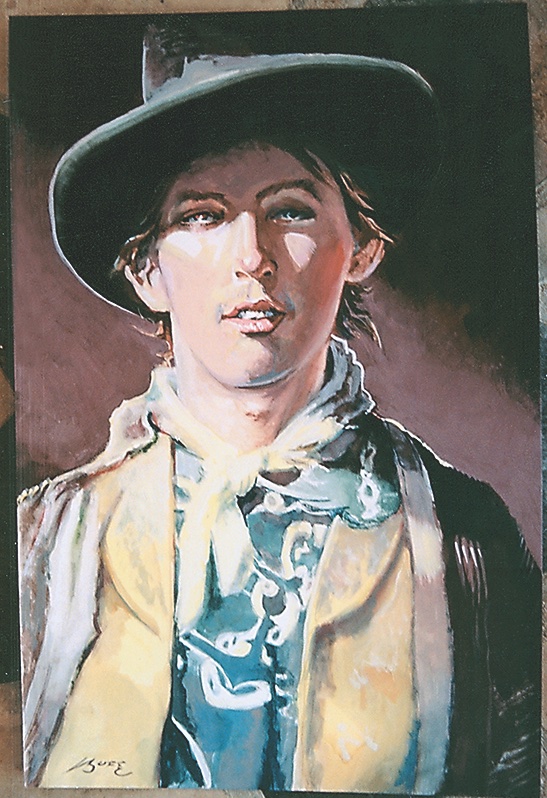

Henry McCarty, aka Billy the Kid, spoke flawless Spanish which endeared him to the local Hispano community. The mutual respect earned him the nickname El Chivato—the Little Goat. All Illustrations by Bob Boze Bell and All Images Courtesy True West Archives Unless Otherwise Noted

Billy was strolling toward the front of the Maxwell house when he suddenly spotted a shadowy figure sitting on the edge of the porch in front of the small gateway leading out toward the old parade ground. He would have spotted this hombre sitting in the darkness sooner had his view not been obstructed by the post of the gate. He quickly pulled his double-action Colt revolver and threw down on the stranger while springing onto the Maxwell porch.

“¿Quién es? (Who is it?)” Billy asked.

Receiving no answer, he began backing away toward Pete Maxwell’s bedroom door.

“¿Quién es?” the Kid asked again.

“¿Quién es?”

The unfamiliar fellow sitting on the edge of the porch stood up and stepped toward him, telling him in Spanish not to be alarmed and that he shouldn’t get hurt. John W. Poe had no idea it was Billy the Kid he was giving these assurances to, thinking it was a guest of Maxwell’s.

Billy didn’t recognize Poe either, having never laid eyes on him. With the shadowy figure of Kip McKinney, whom Billy had also never seen, watching on from outside the fence, John W. Poe continued to advance toward the Kid to reassure him. Billy was unconvinced by the stranger’s assurances and backed into the doorway of Pete Maxwell’s bedroom.

“¿Quién es?” he asked once again, before disappearing from Poe’s sight.

Appearing as a silhouette in the moonlit doorway of Pedro Maxwell’s bedroom, Billy slowly stepped through the darkness across the carpet toward Pete Maxwell’s bed with his revolver in his right hand and the butcher knife in his left. He then leaned forward and reached out toward the presumably asleep Pedro.

“¿Pedro, quiénes son estos hombres afuera? (Pete, who are those men outside?)” the Kid asked.

As Billy reached toward the bed, unbeknownst to him, his hand had almost brushed the knee of Pat Garrett, who was sitting on the side of the bed next to Maxwell. Finally sensing the presence of someone sitting at the head of the bed, Billy raised his revolver and began stepping swiftly back across the room toward the door.

“¿Quién es?” the Kid asked.

“El es (It’s him),” Pete Maxwell whispered as softly as possible to Garrett.

“Who is it?” Billy asked once more while peering through the darkness.

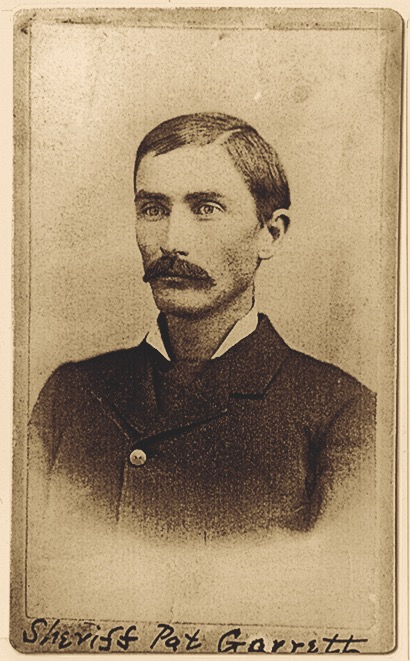

While remaining seated at the head of Maxwell’s bed, Pat Garrett raised his single-action revolver, cocked the hammer, and fired at the silhouette figure standing in the room. With a split-second flash of light filling the bedroom, the shot hit Billy in the left side of his chest, just above the heart. As the Kid fell forward onto the carpet with a horrid burning sensation coursing through his chest, Pat Garrett leaped off the side of the bed and fired another shot, this one ricocheting off a wall and slamming into the headboard of Maxwell’s bed.

Pat Garrett had barely finished squeezing the trigger for the second time before he was bolting from the darkened bedroom, running through the doorway, and brushing past John W. Poe outside. Almost as quickly, Pete Maxwell came running frantically behind him, entangled in bedclothes and almost slamming into Poe, who instinctively raised his gun on him.

“Don’t shoot!” Maxwell cried. “Don’t shoot!”

With his heart racing, Pat Garrett reached over and swatted Poe’s gun downwards.

“Don’t shoot Maxwell!” the sheriff said.

The slight sound of a groan and gasping had been heard coming from inside the bedroom, until silence fell.

“That was the Kid that came in there onto me,” Garrett said to Poe. “And I think I have got him.”

“Pat, the Kid would not have come to this place,” Poe replied. “You have shot the wrong man.”

“I am sure it was him,” Garrett asserted. “I know his voice too well to be mistaken.”

The two shots Pat Garrett had fired were heard throughout Fort Sumner, and residents soon began arriving on the scene. Jesús Silva, Francisco Lovato and Paco Anaya all quickly made their way toward the Maxwell home, with others following suit. When Silva, Lovato and Anaya arrived, they saw Pat Garrett standing alongside his two deputies in front of the Maxwell house. Standing with them were Pete Maxwell, Doña Luz Maxwell and Deluvina Maxwell. Manuel Pedro Abreu and Pablo and Rebecca Beaubien had also made their way there after hearing the shots. Paulita Maxwell was there too, after having been awakened in her bedroom by the gunshots. Many of Fort Sumner’s other residents also began to emerge and wanted to know what had happened. Word was already spreading that Bilito had gone into Don Pedro’s bedroom and been killed.

Pat Garrett was reluctant to venture back inside Pete Maxwell’s bedroom and confirm it was indeed Billy the Kid whom he had shot. Instead, Pat and his deputies watched as Deluvina Maxwell retrieved a lamp.

“¡Voy a entrar! (I’m going in!)” she announced.

Jesús Silva accompanied Deluvina down the porch to Pete Maxwell’s bedroom and cautiously tapped on the door.

“I no want to hurt you, Beely,” Silva called out. “It’s Jesús, and I’m comin’ in!”

When there was no answer, Jesús and Deluvina slowly entered the eerily silent bedroom. As they peered through the darkness with use of the lamp, they found the slight frame of a young man with a head of brown hair lying facedown on the carpet. They turned the lifeless body over and a familiar boyish face appeared within the dim glow of the light. Deluvina immediately started to cry. Henry McCarty, alias William H. Bonney, was dead. He was around 20 or 21 years old. Deluvina soon emerged from Pete Maxwell’s bedroom with tears streaming down her face.

“¡Mí chiquito está muerto!” (My little boy is dead!) she cried.

The Navajo woman’s sobbing soon turned to rage as she proceeded to unleash a verbal tirade on Pat Garrett, calling him every vile name she could lace her tongue to.

“You pisspot!” Deluvina cursed him while thumping his chest. “You son of a bitch!”

Pete Maxwell procured a tallow candle from Doña Luz’s bedroom at the other end of the house. He placed it on the windowsill before accompanying Pat Garrett and Kip McKinney into the room. Making their own examination of the scene, Poe recalled, “We saw a man lying stretched upon his back, dead, in the middle of the room, with a six-shooter lying at his right hand and a butcher knife at his left. Upon examining the body, we found it to be that of Billy the Kid.”

“We searched long and faithfully—found both my bullet marks and none other,” recalled Pat Garrett. “We examined his pistol—a self-cocker, caliber 41. It had five cartridges and one shell in the chambers, the hammer resting on the shell… [T]his shell looked as though it had been shot sometime before.”

“There wasn’t even one Mexican cent in the outlaw’s pockets when the officers searched him,” recalled Jesús Silva. “Pat Garrett took his gun.”

At one point, John W. Poe saw Paulita Maxwell standing and observing Billy’s body for a considerable length of time. Her face was inexpressive, presumably from shock. The tears eventually came, and she had to be consoled by other young women in the vicinity. If Billy had spoken truthfully when telling Martín Chávez of his willingness to die for Paulita several months earlier, then he had fulfilled his vow.

Cursed and Despised

With Deluvina Maxwell and Jesús Silva confirming Billy’s death, their anger was soon shared by many Hispanos who gathered at the scene. While some of the señoritas cried and consoled each other, men shook their fists in anger and cursed the gringo lawmen. “Billy had been very popular at Fort Sumner and had a great many friends, all of whom were indignant toward Pat Garrett,” recalled Francisco Lovato. “If a leader had been present, Garrett and his two officers would have received the same fate they dealt Billy.”

With tensions rising and some of the Hispanos hurling insults at them also being armed, Pat Garrett, John W. Poe and Kip McKinney retreated into the Maxwell home. “We spent the remainder of the night on the Maxwell premises, keeping constantly on our guard, as we expected attack by the friends of the dead man,” recalled Poe.

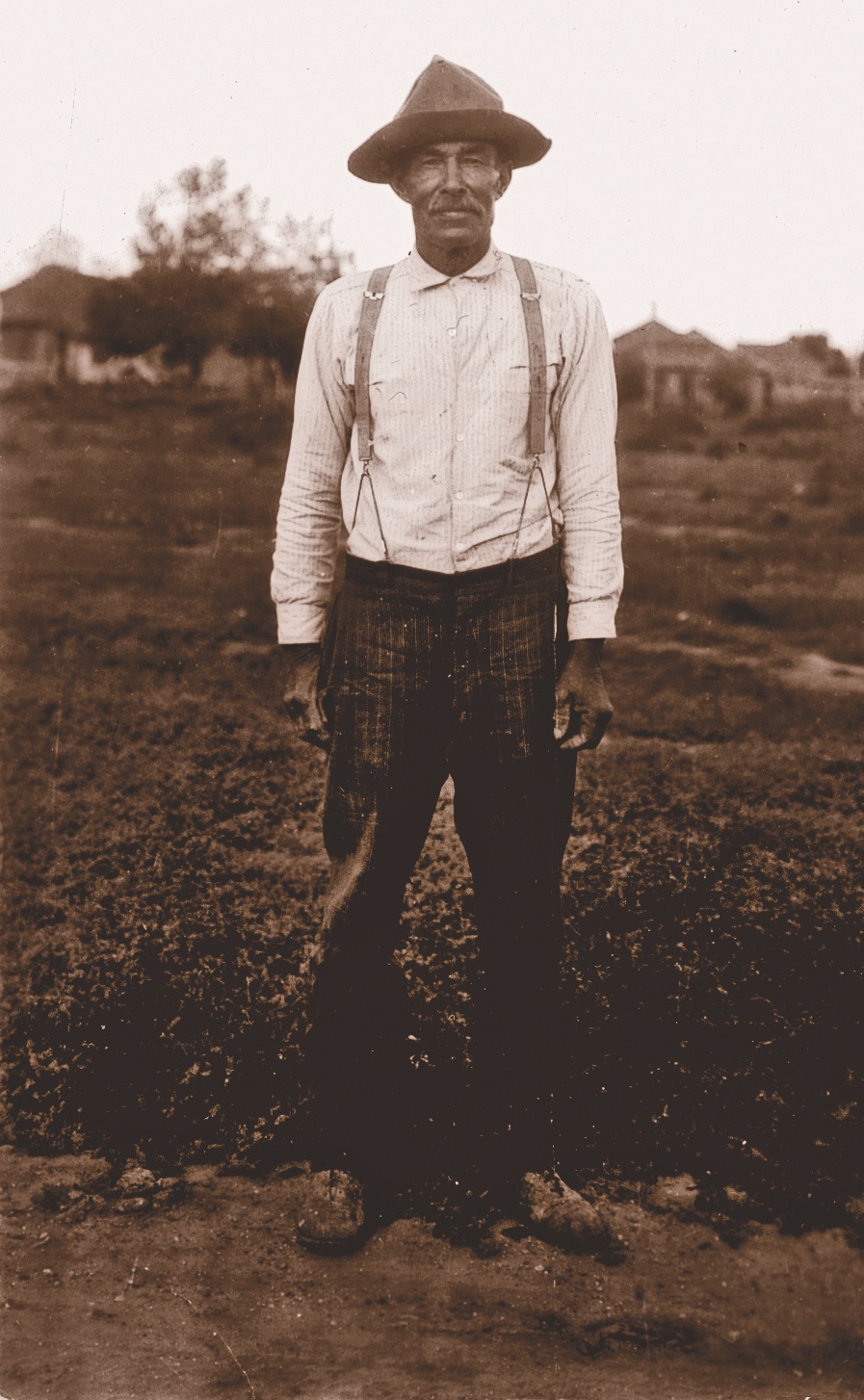

“Pat Garrett and his two companions were badly frightened, and did not dare to sleep that night,” remembered Jesús Silva. “They remained awake, arms in readiness for any emergency.” Despite the outrage expressed by so many, no attempt at reprisal was made. “Someone in Fort Sumner must have given Billy away,” Silva later correctly surmised.

Jesús Silva and several señoritas asked permission to move Billy’s body. At

Pete Maxwell’s suggestion, William Bonney’s slender corpse was carried out of his bedroom to the old carpenter shop on the eastern side of the fort and laid out on a workbench. After his fatal gunshot wound was sealed with a rag, Hispano women gently washed and cleaned the Kid’s body in preparation for his impending wake. Candles were soon lit and placed around his corpse as part of “properly conducting a wake for the dead,” John W. Poe recalled. While Deluvina Maxwell and Hispano women cried and prayed over Billy’s body, Vicente Otero stood observing the wake the remainder of the night along with Juan Medina, Juan Nepamuceno Pacheco and many more of the Kid’s amigos.

Word of Billy’s death spread quickly throughout the old fort, with frantic messengers running to each adobe residence to share the news with those who hadn’t heard it. With many locals arriving in the vicinity, the question “who killed him?” was asked by many and soon answered for all. Many señoritas and señoras wailed in grief, crying “pobre Beely (poor Billy).” It was a sentiment later shared by Jesús Silva.

“Poor old Billy,” Silva said years later. “Billy was a good boy—he just had to do that way.”

A Local Hero’s Hispano Funeral

On the morning of July 15, 1881, a coffin was constructed by Jesús Silva with help from Vicente Otero and others. Pat Garrett had advised them to use ceiling planks stripped from an abandoned adobe house for the coffin’s construction. Garrett also gave Pete Maxwell $25 to buy some new clothes in which Billy’s corpse could be dressed for burial. Maxwell accompanied Manuel Abreu to his store, where he purchased a beige suit, shirt, undergarments and a pair of stockings. Paco Anaya, his brother-in-law, Iginio García, and several others then dressed Billy’s corpse in the new clothes.

Word of Billy the Kid’s death had spread rapidly through the surrouning countryside, and Fort Sumner was soon inundated with the arrivals of Milnor Rudolph, Mike Cosgrove and others. At Pat Garrett’s insistence, a coroner’s report was held. Justice of the Peace Alejandro Segura had been sent for to conduct the report and appoint a coroner’s jury. The jury included Milnor Rudolph, who acted as foreman, along with Saval Gutiérrez, 37-year-old sheepherder Lorenzo Jaramillo, Pedro Antonio Lucero, Antonio Savedra and José Silva. Except for the Kid’s final words, the report was written entirely in Spanish, with the illiterate Gutiérrez, Jaramillo, and Silva signing with an “X.” The coroner’s report ended with the declaration:

We the jury unanimously find that William Bonney has been killed by a bullet in the left breast in the region of the heart, the same having been fired from a pistol in the hand of Pat F. Garrett, and our verdict is that the act of said Garrett was justifiable homicide and we are unanimous in the opinion that the gratitude of all the community is due to the said Garrett for his deed and is worthy of being rewarded.

The final sentence was certainly written at the behest of Pat Garrett to ensure he would be able to claim the $500 reward money from acting-Governor William Ritch. While some citizens throughout the Territory would later shake Garrett’s hand and congratulate him for ridding the Southwest of a notorious outlaw, the majority of Hispano citizens of Fort Sumner were hardly grateful to him, nor would they have felt he was worthy of being rewarded for killing their Bilito in the middle of the night.

After Billy’s body was placed in his coffin, it was moved to Beaver Smith’s saloon, where it remained on display until time for burial. Jesús Silva and Vicente Otero dug a grave down in the old cemetery. In the afternoon, William H. Bonney’s coffin was sealed and loaded into the back of Vicente Otero’s creaky old wagon. With a throng of at least 170 people following behind, the coffin was slowly led down to the fort’s old military cemetery by two lean ponies, with the loud creaking from the turning wheels of Otero’s rickety wagon serving as Billy’s requiem mass.

“Most of the native people who lived in town went to his funeral,” recalled Deluvina Maxwell. “Practically every man, woman and child in town followed the body to the little cemetery,” remembered Paulita Maxwell.

When the large funeral procession reached the old military cemetery, pallbearers Jesús Silva, Paco Anaya, Vicente Otero, Saval Gutiérrez, Antonio Savedra and others lowered the coffin into the freshly dug grave to the southwest of the northern entrance. In the opposite direction of the northeast corner lay the unmarked graves of Tom Folliard, Charlie Bowdre and Joe Grant.

After the coffin was lowered and the grave filled, a sermon in Spanish was likely said by someone before the large congregation dispersed. Sheriff Pat Garrett dismissed his two deputies and rode out of Fort Sumner with Pete Maxwell after carrying out the job he had been elected to do. He was riding for Las Vegas before heading to Santa Fe. After meeting resistance from acting-Governor William Ritch over the $500 reward, he met with Thomas B. Catron and Marcus Brunswick for support in attempting to secure the money. “There was no use chasing him in that country with the start he had,” Garrett later said. “I waited until I thought he would reach his sweetheart’s at the Maxwell ranch house, and—I got him.”

After a small cross placed at his gravesite crudely bearing his most famous alias had been stolen a short time later, the grave of Henry McCarty, aka William H. Bonney, was marked by a plain board bearing the stenciled words:

BILLY THE KID

Deluvina Maxwell, forever harboring an intense hatred for Pat Garrett and his deputies, left flowers on the grave of her chiquito in the summer for many years. One can only imagine her reaction had she known the role Pedro Maxwell had played in bringing about her little boy’s death.

In Anton Chico, Padre Antonio Redon could be heard to remark, “Billy did not have a bad heart; most of his crimes were those of vengeance.” Two weeks after William Bonney’s death, the Grant County Herald offered its own epitaph; “He was a low-down vulgar cut-throat, with probably not one redeeming quality.”

No “low-down vulgar cut-throat” was ever so well-liked and fondly remembered by so many who knew him.

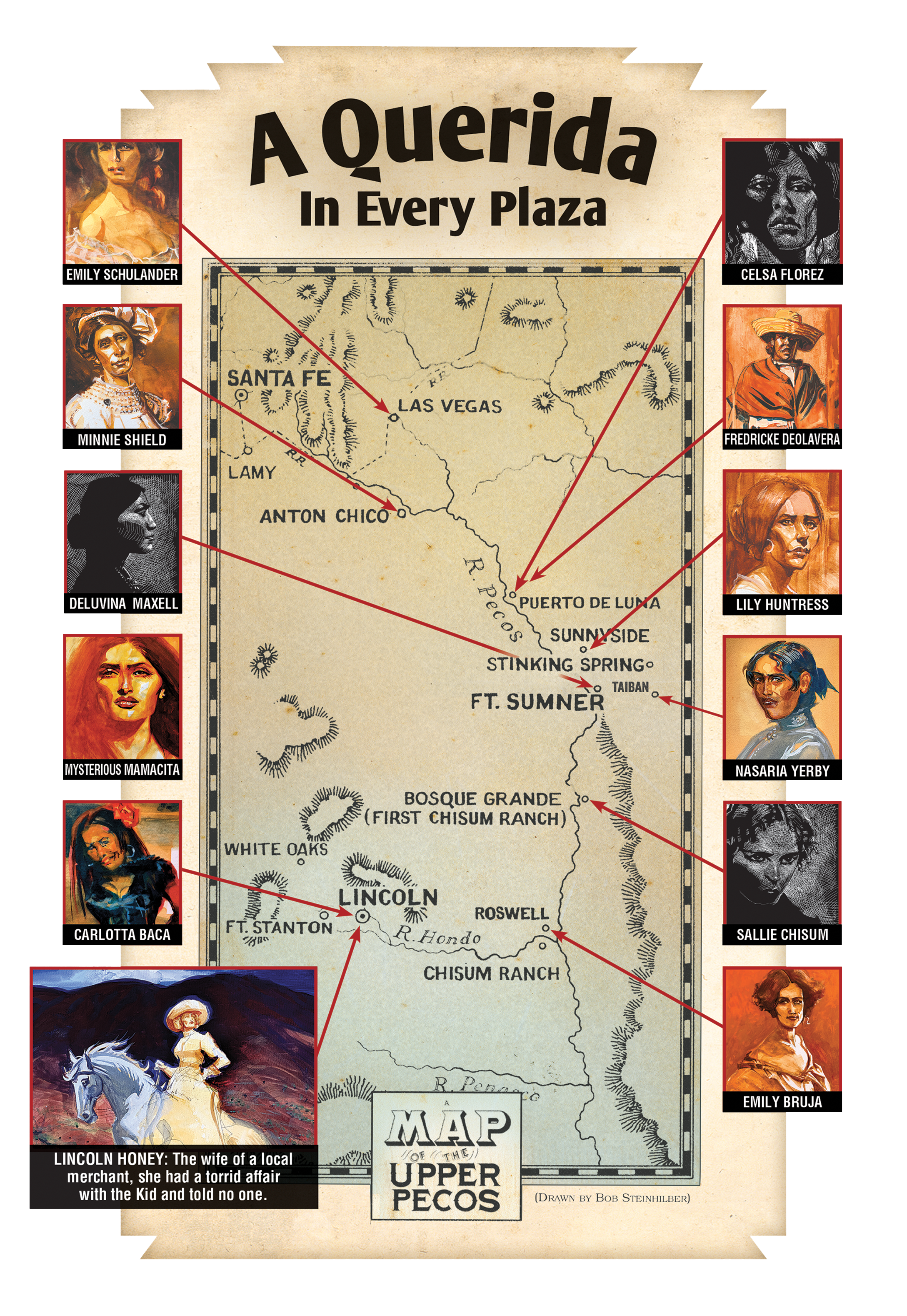

As we have already seen, Billy had many affairs with beautiful women up and down the Pecos. Legend says one of them, from Anton Chico, haunted his dreams to the day he died.

James B. Mills was born in 1983 and resides in Australia. His next book, In The Days of Billy the Kid: The Frontier Lives of José Chávez y Chávez, Juan Patrón, Martín Chávez, and Yginio Salazar, is currently in the works.

Editor’s Note: “A Fitting Funeral for Billy the Kid What Really Happened to El Chivato?” is an exclusive excerpt from Billy the Kid: El Bandido Simpático by James B. Mills, published by the University of North Texas Press.

El Bandido Simpático