– Courtesy John Hart Collection –

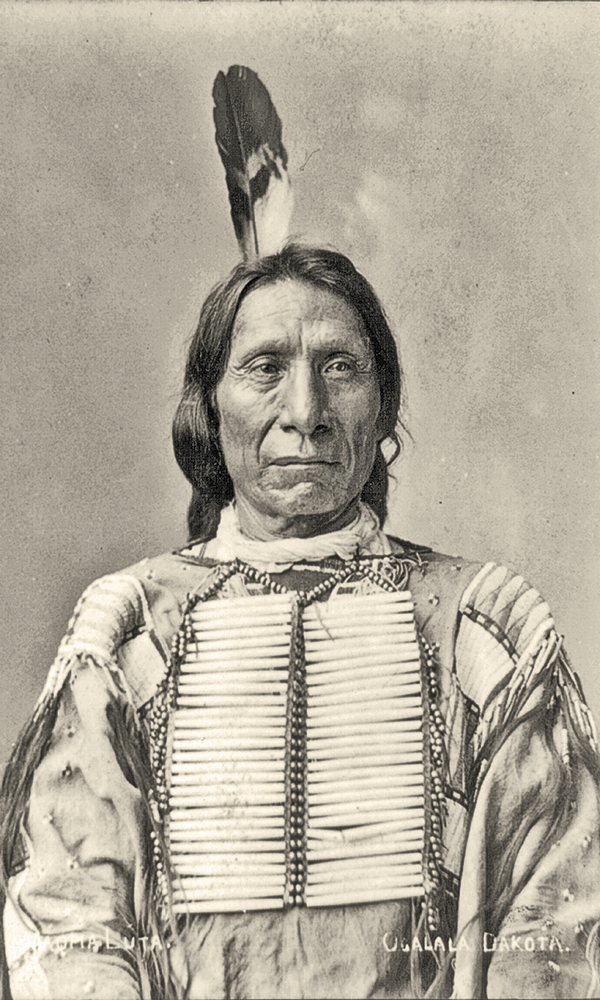

In July 1867, leaders of the Sioux and Northern Cheyenne tribes gathered on Rosebud Creek in Montana Territory to plan the next phase in their most successful war.

The tribes were allies in a fight to shut down the Bozeman Trail, which had been siphoning Montana Territory-bound miners north from the Platte River Road since 1864. An intrusion into country the Indians regarded as an ultimate heartland, it confirmed their fear that, treaties or no, the white tide would never stop rising.

In the previous December, the tribes had scored a signal victory outside U.S. Army Fort Phil Kearny, threatening a wood-cutting party and annihilating the soldiers sent to relieve it: the Fetterman Fight, called (like other lopsided Indian victories) a “massacre.”

After a long winter pause, the warriors were ready to try again. Their objective would be one of two hated federal forts on the Bozeman: perhaps Fort Phil Kearny again; perhaps Fort C.F. Smith, 90 miles beyond Fort Phil Kearny, on the Bighorn River. Some favored one; some, the other.

Unable to agree, the chiefs decided to split their forces. The result was a pair of notable battles: the Hayfield Fight near Fort C.F. Smith on August 1 and the Wagon Box Fight outside Fort Phil Kearny on August 2.

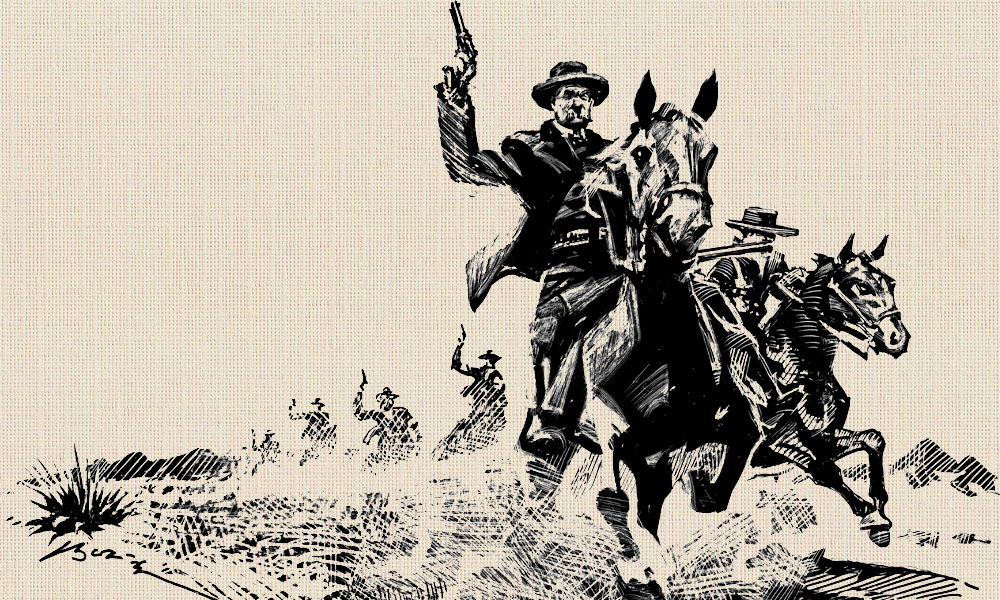

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

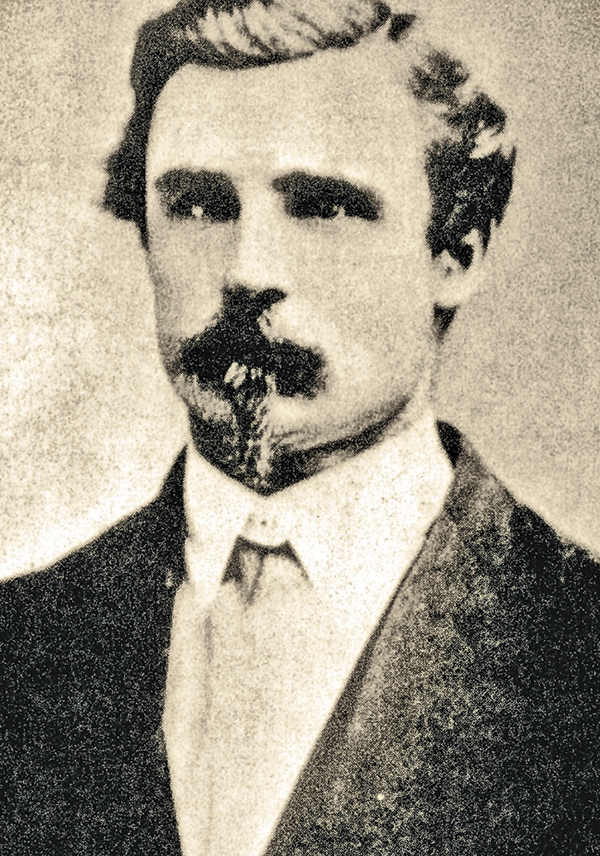

Of the two, Wagon Box has received more attention. A bombastic monument for it was erected in 1936, followed by a more balanced presentation on modern interpretive plaques. The Hayfield Fight, by contrast, is little remarked. One reason for that is the paucity of eyewitnesses: all accounts rest on the memories of just two men, teamster Fincelius “Finn” Burnett and U.S. Army Pvt. James D. Lockwood. Both of their accounts were committed to paper decades after the event.

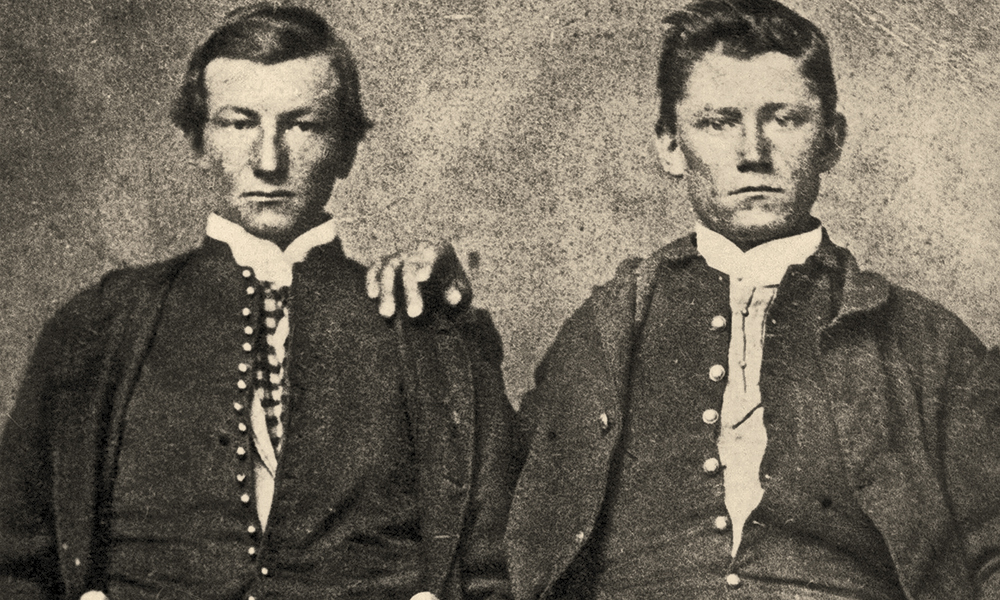

Now, we have a third eyewitness. John Benton Hart, like Burnett a civilian employee of the Army, was also on hand. In the 1920s, pushing 80, he dictated extensive memoirs of his Civil War and frontier experiences to his son Harry.

Johnny arrived at Fort C.F. Smith on July 23 as a bullwhacker with a Wells, Fargo & Company wagon train. He and his twin brother, Hugh, had joined the train that spring in North Platte, Nebraska, then the westernmost town on the Union Pacific Railroad. The brothers’ goal was to work the new mining district in Montana Territory, possibly Virginia City, but first they took a job cutting hay for the fort, under civilian contractors William S. McKenzie and Al Colvin.

On August 1, the wagon train headed back south, reducing the strength of the isolated garrison. It was the Indians’ cue to attack. Johnny and Hugh were at the hay-cutting site, approximately three miles north along the Bighorn River, with about 30 other laborers and soldiers. Among these were Colvin, McKenzie, Johnny’s half-Indian friend Charley Smith and presumably Burnett and Lockwood.

The corral was “quite a formidable place in which to fight Indians,” Johnny stated, continuing his description of the camp’s defenses: “Our corral was a large one. It was made of cottonwood trees of all sizes laid every way, one on top of another in zigzag fashion. On the outside trees had been snaked down from a ridge, then upended on the corral until it made a kind of stockade ten or 12 feet through in some places and in some places fully that high.”

Under Attack

Johnny had experience combatting Indians on the frontier, as well as Confederates, while serving as a private with the 11th Kansas Cavalry during the Civil War. Nine days after his arrival at Fort C.F. Smith, he was about to encounter yet another siege.

“A way off we could see Indians in bunches of ten and twelve on all sides,” Johnny recalled. “Gradually they increased in size and kept coming nearer and nearer to us. After a while we could hear their war songs. ‘That means business, boys,’ McKenzie exclaimed. ‘Don’t a one of you shoot before sure of hitting an Indian or pony. Keep cool and don’t become rattled.’

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

Johnny and the hay cutters found themselves challenged immediately. “‘There is a good Indian marksman shooting across the little creek and he came near to getting me,’ Hugh said, as he came into the corral after…[gathering] wood [to build up the barricade].”

Sure enough, the marksman found his mark, Lt. Sigismund Sternberg, and blew away his brains. Colvin, who had Civil War experience, became the de facto commander. The next casualty came while a soldier was rifling through Sternberg’s clothing, to grab his watch, purse and other articles—an Indian killed that scavenger.

“He was lying across the lieutenant’s body, shot in the chest,” Johnny stated. “I ran over and pulled the dead soldier off the lieutenant’s body.

“‘What did you do that for?’ Al Colvin asked.”

“‘The soldier,’ I answered, ‘is a scavenger. I do not want him to bleed on the lieutenant.’

The men commenced looking for the skilled marksman. “After close observing with a field glass and watching when he fired, located his hiding place. It was a wonder we had not discovered him before, as he was so close to us and did not have such a secure place as we thought,” Johnny stated. “When he fired at a hat cunningly placed in a hole, all our boys would fire in the direction where smoke flared from his gun.

“We heard a yell and his bullets stopped coming. I think very likely he went to his happy hunting ground, at any rate he troubled us no more.”

The attacks continued to come, notably one that Johnny called the “log round.”

“After a while we noticed a few logs between our corral and the creek. These logs appeared to be rolling toward us at first but were coming slow. It was a little odd and uncanny this thing of life in a lifeless log.

“Gradually these logs crept up in their rolling way pretty close to our corral, and then there began to be shots fired at us from behind these logs by [a] pretty good marksman for Indians.

– Courtesy University of Oklahoma Press –

“Stop them we must before they came too close. Our bullets would not go through them. They acted as a moving fort against our stationary one.

“‘Just watch me,’ Jack Hemphill said. ‘I am going to shoot right under that log and tear all that Indian’s digestive tract out, if he has any.’

“Jack drew a fine bead holding under the log so as to make the bullet bounce up under the log as it hit the earth or go through the under portion of the log. He squirmed and granted a bit, holding his breath, fussing, and then fired.

“Up jumped an Indian like a bird, all spraddled out clear above the log and yelling at the top of his voice.

“After that all the logs moved off toward the little creek, much to our joy.”

The victory was only momentary. The next charge would be more serious.

Looking Like the Last of Us

“Soon down on us they came, all yelling like wild creatures of some new kind of inferno,” Johnny stated. “…This charge was almost as bad as any before and came near being fatal for us, as the ones behind kept crowding the ones in front closer in. They were jumping off their ponies and running all around our corral looking for a man to kill.

“Our shots were telling to deadly effect. Even as it did look like the last of us, this crowding and jamming, especially if all should dismount and storm our temporary fort at once.

“We steadily kept shooting their ponies, and shooting all Indians that attempted to scale our corral. If one side should be pressed pretty hard, those on the other side would rise up quickly and fire over the backs of the mules and horses and we would do the same when they were being pressed hard on their side.

“It was getting pretty warm for us, disastrous for them, as their wounded and death list rapidly increased. Our stock in corral was rapidly being shot to pieces. Some of our wagons were being moved away a couple of yards, and they had commenced to move up some of the trees and stumps of the fence. To stop this we fired whole volleys in one place…. If we had not chained the wagons together at the gate of corral, all would have been up with us.”

The superior firepower was buying the party time. The same wagon train that brought Johnny to the fort carried a shipment of the latest breech-loading Springfield rifles, which—unlike the muzzleloaders used in the Fetterman Fight a few months earlier—could be fired with little interruption. The Indians were dismayed by this.

The Mule of the Hour

After repelling yet another attack, the beleaguered party sent a messenger for help. His name, unknown to Johnny, was Pvt. Charles Bradley.

“During this silence or semi-silence that followed, a little soldier who was with us asked McKenzie for a mule to ride to the fort,” Johnny stated. “We would get killed anyhow, the little soldier said, and he would just as well die to get help from the fort as to stay here and die doing nothing.

“‘No!’ McKenzie answered, ‘No mule of mine shall leave this corral.’

“Finally the little soldier asked Al Colvin for a mule named Little Dock, the best running mule in the corral. Al Colvin was provoked, but after a few minutes gave in.

“We caught Little Dock and put a blind bridle on him. Then hoisted the little soldier on his back, wishing him a thousand Godspeeds. We shoved wagons away from the front of the corral, then out the soldier and Little Dock went.

“Little Dock went walking on the front part of his hooves as if trying to walk in the air and somewhat stiff-legged but springy in his movements like a deer. Once outside of the corral the soldier turned the mule loose and prepared himself in such a manner as to hold on. They looked mighty alone running out there.

“As expected, the Indians opened up their lines on seeing the soldier coming, in the shape of a V, then closed in on him from behind. They did not want to kill the soldier, wanted to take him alive so as to force him to die at their leisure.

“The mule bolted for the swamp toward the Bighorn River. After that we held our breath, for all we could see was a cloud of dust and Indians going for the soldier in all directions.

“The lookout on the logs hollered, ‘There is something strange down there at the end of the swamp. All the Indians are going on the run toward the fort and around the end of the swamp.’

“We climbed upon the trees and logs of our corral to take a look. Away and there in the lead ran Little Dock and the soldier. Through McKenzie’s glass could see Little Dock’s front legs reaching out in front of him and they did not seem to come back, they seemed always there, so quick did he gather them. He had too much of a lead for the Indians to ever catch him.

“‘How on earth did the soldier cross that swamp?’ McKenzie shouted. ‘He has gained the wood road. The Sioux are too wise to cross that swamp so are going around.’”

As the warriors watched Little Dock ride toward the fort, “[the] Indians knew the soldiers would soon be down there with their wagons on wheels to shoot at them,” Johnny wrote. “They were going to give us [hay cutters] one more round before the soldiers came to our aid.”

The Last Chance Round

“We could see this time the Indian pony was not going to figure in the charge at all,” Johnny stated. “It was going to be a foot charge, the very thing we dreaded from the beginning that day.